Borderline personality disorder

Borderline personality disorder (BPD), also known as emotionally unstable personality disorder (EUPD),[9] is a mental illness characterized by a long-term pattern of unstable relationships, distorted sense of self, and strong emotional reactions.[4][5][10] Those affected often engage in self-harm and other dangerous behavior.[4] They may also struggle with a feeling of emptiness, fear of abandonment, and detachment from reality.[4] Symptoms of BPD may be triggered by events considered normal to others.[4] BPD typically begins by early adulthood and occurs across a variety of situations.[5] Substance abuse, depression, and eating disorders are commonly associated with BPD.[4] Approximately 10% of people affected with the disorder die by suicide.[4][5] The disorder is often stigmatized in both the media and the psychiatric field.[11]

| Borderline personality disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | |

| |

| Idealization is seen in Edvard Munch's The Brooch. Eva Mudocci (1903)[3] | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Unstable relationships, sense of self, and emotions; impulsivity; recurrent suicidal behavior and self-harm; fear of abandonment; chronic feeling of emptiness; inappropriate anger; feeling detached from reality[4][5] |

| Complications | Suicide[4] |

| Usual onset | Early adulthood[5] |

| Duration | Long term[4] |

| Causes | Unclear[6] |

| Risk factors | Family history, trauma, abuse[4][7] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on reported symptoms[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Identity disorder, mood disorders, post traumatic stress disorder, cptsd, substance use disorders, histrionic, narcissistic, or antisocial personality disorder[5][8] |

| Treatment | Behavioral therapy[4] |

| Prognosis | Improves over time[5] |

| Frequency | 1.6% of people in a given year[4] |

| Personality disorders |

|---|

| Cluster A (odd) |

| Cluster B (dramatic) |

| Cluster C (anxious) |

| Not specified |

The causes of BPD are unclear but seem to involve genetic, neurological, environmental, and social factors.[4][6] It occurs about five times more often in a person who has an affected close relative.[4] Adverse life events appear to also play a role.[7] The underlying mechanism appears to involve the frontolimbic network of neurons.[7] BPD is recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) as a personality disorder, along with nine other such disorders.[5] The condition must be differentiated from an identity problem or substance use disorders, among other possibilities.[5]

BPD is typically treated with psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or dialectical behavior therapy (DBT).[4] DBT may reduce the risk of suicide in the disorder.[4] Therapy for BPD can occur one-on-one or in a group.[4] While medications cannot cure BPD, they may be used to help with the associated symptoms.[4] Severe cases of the disorder may require hospital care.[4]

About 1.6% of people have BPD in a given year, with some estimates as high as 6%.[4][5] Women are diagnosed about three times as often as men.[5] The disorder appears to become less common among older people.[5] Up to half of those with BPD improve over a ten-year period.[5] Those affected typically use a high amount of healthcare resources.[5] There is an ongoing debate about the naming of the disorder, especially the suitability of the word borderline.[4]

Signs and symptoms

BPD is characterized by the following signs and symptoms:

- Markedly disturbed sense of identity

- Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment, and extreme reactions to such

- Splitting ("black-and-white" thinking)

- Impulsive or reckless behaviors (e.g., impulsive or uncontrollable spending, unsafe sex, substance abuse, reckless driving, binge eating)[12]

- Intense or uncontrollable emotional reactions that are disproportionate to the event or situation

- Unstable and chaotic interpersonal relationships

- Self-damaging behavior

- Distorted self-image[4]

- Dissociation

- Frequently accompanied by depression, anxiety, anger, substance abuse, or rage

Overall, the most distinguishing symptoms of BPD are marked sensitivity to minor rejection or criticism;[13] alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation of others, along with varying moods and difficulty regulating strong emotional reactions. Dangerous and impulsive behavior are also correlated with the disorder.

Other symptoms may include feeling unsure of one's personal identity, morals, and values; having paranoid thoughts when feeling stressed; depersonalization; and, in moderate to severe cases, stress-induced breaks with reality or psychotic episodes.

Emotions

People with BPD may feel emotions with greater ease and depth and for a longer time than others do.[14][15] A core characteristic of BPD is affective instability, which generally manifests as unusually intense emotional responses to environmental triggers, with a slower return to a baseline emotional state.[16][17] According to Marsha Linehan, the sensitivity, intensity, and duration with which people with BPD feel emotions have both positive and negative effects.[17] People with BPD are often exceptionally enthusiastic, idealistic, joyful, and loving,[18] but may feel overwhelmed by negative emotions (anxiety, depression, guilt/shame, worry, anger, etc.), experiencing intense grief instead of sadness, shame and humiliation instead of mild embarrassment, rage instead of annoyance, and panic instead of nervousness.[18]

People with BPD are also especially sensitive to feelings of rejection, criticism, isolation, and perceived failure.[19] Before learning other coping mechanisms, their efforts to manage or escape from their very negative emotions may lead to emotional isolation, self-injury or suicidal behavior.[20] They are often aware of the intensity of their negative emotional reactions and, since they cannot regulate them, shut them down entirely since awareness would only cause further distress.[17] This can be harmful since negative emotions alert people to the presence of a problematic situation and move them to address it.[17]

While people with BPD feel euphoria (ephemeral or occasional intense joy), they are especially prone to dysphoria (a profound state of unease or dissatisfaction), depression, and/or feelings of mental and emotional distress. Zanarini et al. recognized four categories of dysphoria typical of this condition: extreme emotions, destructiveness or self-destructiveness, feeling fragmented or lacking identity, and feelings of victimization.[21] Within these categories, a BPD diagnosis is strongly associated with a combination of three specific states: feeling betrayed, feeling out of control, and "feeling like hurting myself".[21] Since there is great variety in the types of dysphoria people with BPD experience, the amplitude of the distress is a helpful indicator.[21]

In addition to intense emotions, people with BPD experience emotional "lability" (changeability, or fluctuation). Although that term suggests rapid changes between depression and elation, mood swings in people with BPD more frequently involve anxiety, with fluctuations between anger and anxiety and between depression and anxiety.[22]

Interpersonal relationships

People with BPD can be very sensitive to the way others treat them, by feeling intense joy and gratitude at perceived expressions of kindness, and intense sadness or anger at perceived criticism or hurtfulness.[23] People with BPD often engage in idealization and devaluation of others, alternating between high positive regard for people and great disappointment in them.[24] Their feelings about others often shift from admiration or love to anger or dislike after a disappointment, a threat of losing someone, or a perceived loss of esteem in the eyes of someone they value. This phenomenon is sometimes called splitting.[25] Combined with mood disturbances, idealization and devaluation can undermine relationships with family, friends, and co-workers.[26]

While strongly desiring intimacy, people with BPD tend toward insecure, avoidant or ambivalent, or fearfully preoccupied attachment patterns in relationships,[27] and often view the world as dangerous and malevolent.[23] Like other personality disorders, BPD is linked to increased levels of chronic stress and conflict in romantic relationships, decreased satisfaction of romantic partners, abuse, and unwanted pregnancy.[28]

Behavior

Impulsive behavior is common, including substance or alcohol abuse, eating in excess, unprotected sex or indiscriminate sex with multiple partners, reckless spending, and reckless driving.[29] Impulsive behavior may also include leaving jobs or relationships, running away, and self-injury.[30] People with BPD might do this because it gives them the feeling of immediate relief from their emotional pain,[30] but in the long term may feel shame and guilt over consequences of this behavior.[30] A cycle often begins in which people with BPD feel emotional pain, engage in impulsive behavior to relieve that pain, feel shame and guilt over their actions, feel emotional pain from the shame and guilt, and then experience stronger urges to engage in impulsive behavior to relieve the new pain.[30] As time goes on, impulsive behavior may become an automatic response to emotional pain.[30]

Self-harm and suicide

Self-harming or suicidal behavior is one of the core diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5.[5] Self-harm occurs in 50 to 80% of people with BPD. The most frequent method of self-harm is cutting.[31] Bruising, burning, head banging or biting are not uncommon with BPD.[31] People with BPD may feel emotional relief after cutting themselves.[32]

The lifetime risk of suicide among people with BPD is between 3% and 10%.[13][33] There is evidence that men diagnosed with BPD are approximately twice as likely to die by suicide as women diagnosed with BPD.[34] There is also evidence that a considerable percentage of men who die by suicide may have undiagnosed BPD.[35]

The reported reasons for self-harm differ from the reasons for suicide attempts.[20] Nearly 70% of people with BPD self-harm without trying to end their lives.[36] Reasons for self-harm include expressing anger, self-punishment, generating normal feelings (often in response to dissociation), and distracting oneself from emotional pain or difficult circumstances.[20] In contrast, suicide attempts typically reflect a belief that others will be better off following the suicide.[20] Suicide and self-harm are responses to feeling negative emotions.[20] Sexual abuse can be a particular trigger for suicidal behavior in adolescents with BPD tendencies.[37]

Sense of self

People with BPD tend to have trouble seeing their identity clearly. In particular, they tend to have difficulty knowing what they value, believe, prefer, and enjoy.[38] They are often unsure about their long-term goals for relationships and jobs. This can cause people with BPD to feel "empty" and "lost".[38] Self-image can also change rapidly from healthy to unhealthy.

Cognitions

The often intense emotions people with BPD experience can make it difficult for them to concentrate.[38] They may also tend to dissociate, which can be thought of as an intense form of "zoning out".[39] Others can sometimes tell when someone with BPD is dissociating because their facial or vocal expressions may become flat or expressionless, or they may appear distracted.[39]

Dissociation often occurs in response to a painful event (or something that triggers the memory of a painful event). It involves the mind automatically redirecting attention away from that event—presumably to protect against intense emotion and unwanted behavioral impulses that such emotion might trigger.[39] The mind's habit of blocking out intense painful emotions may provide temporary relief, but it can also have the side effect of blocking or blunting ordinary emotions, reducing the access of people with BPD to the information those emotions provide, information that helps guide effective decision-making in daily life.[39]

Psychotic symptoms

Though BPD is primarily seen as a disorder of emotional regulation, psychotic symptoms are fairly common, with an estimated 21-54% prevalence in clinical BPD populations.[40] These symptoms are sometimes referred to as “pseudo-psychotic” or “psychotic-like,” terms that suggest a distinction from those seen in primary psychotic disorders. Recent research, however, has indicated that there is more similarity between pseudo-psychotic symptoms in BPD and “true” psychosis than originally thought.[40][41] Some researchers critique the concept of pseudo-psychosis for, on top of weak construct validity, the implication that it’s “not true” or “less severe,” which could trivialize distress and serve as a barrier to diagnosis and treatment. Some researchers have suggested classifying these BPD symptoms as “true” psychosis, or even eliminating the distinction between pseudo-psychosis and true psychosis altogether.[40][42]

The DSM-5 recognizes transient paranoia that worsens in response to stress as a symptom of BPD.[5] Studies have documented both hallucinations and delusions in BPD patients who lack another diagnosis that would better account those symptoms.[41] Phenomenologically, research suggests that auditory verbal hallucinations found in patients with BPD cannot be reliably distinguished from those seen in schizophrenia.[41][42] Some researchers suggest there may be a common etiology underlying hallucinations in BPD and those in other conditions like psychotic and affective disorders.[41]

Disability

Many people with BPD are able to work if they find appropriate jobs and their condition is not too severe. People with BPD may be found to have a disability in the workplace if the condition is severe enough that the behaviors of sabotaging relationships, engaging in risky behaviors or intense anger prevent the person from functioning in their job role.[43]

Causes

As is the case with other mental disorders, the causes of BPD are complex and not fully agreed upon.[44] Evidence suggests that BPD and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be related in some way.[45] Most researchers agree that a history of childhood trauma can be a contributing factor,[46] but less attention has historically been paid to investigating the causal roles played by congenital brain abnormalities, genetics, neurobiological factors, and environmental factors other than trauma.[44][47]

Social factors include how people interact in their early development with their family, friends, and other children.[48] Psychological factors include the individual's personality and temperament, shaped by their environment and learned coping skills that deal with stress.[48] These different factors together suggest that there are multiple factors that may contribute to the disorder.[49]

Genetics

The heritability of BPD is estimated to be between 37% to 69%.[50] That is, 37% to 69% of the variability in liability underlying BPD in the population can be explained by genetic differences. Twin studies may overestimate the effect of genes on variability in personality disorders due to the complicating factor of a shared family environment.[51] Even so, the researchers of one study concluded that personality disorders "seem to be more strongly influenced by genetic effects than almost any Axis I disorder [e.g., depression, eating disorders], and more than most broad personality dimensions".[52] Moreover, the study found that BPD was estimated to be the third most-heritable personality disorder out of the 10 personality disorders reviewed.[52] Twin, sibling, and other family studies indicate partial heritability for impulsive aggression, but studies of serotonin-related genes have suggested only modest contributions to behavior.[53]

Families with twins in the Netherlands were participants of an ongoing study by Trull and colleagues, in which 711 pairs of siblings and 561 parents were examined to identify the location of genetic traits that influenced the development of BPD.[54] Research collaborators found that genetic material on chromosome 9 was linked to BPD features.[54] The researchers concluded that "genetic factors play a major role in individual differences of borderline personality disorder features".[54] These same researchers had earlier concluded in a previous study that 42% of variation in BPD features was attributable to genetic influences and 58% was attributable to environmental influences.[54] Genes under investigation as of 2012 include the 7-repeat polymorphism of the dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) on chromosome 11, which has been linked to disorganized attachment, whilst the combined effect of the 7-repeat polymorphism and the 10/10 dopamine transporter (DAT) genotype has been linked to abnormalities in inhibitory control, both noted features of BPD.[55] There is a possible connection to chromosome 5.[56]

Brain abnormalities

A number of neuroimaging studies in BPD have reported findings of reductions in regions of the brain involved in the regulation of stress responses and emotion, affecting the hippocampus, the orbitofrontal cortex, and the amygdala, amongst other areas.[55] A smaller number of studies have used magnetic resonance spectroscopy to explore changes in the concentrations of neurometabolites in certain brain regions of BPD patients, looking specifically at neurometabolites such as N-acetylaspartate, creatine, glutamate-related compounds, and choline-containing compounds.[55]

Some studies have identified increased gray matter in areas such as the bilateral supplementary motor area, dentate gyrus, and bilateral precuneus, which extends to the bilateral posterior cingulate cortex (PCC).[57] The hippocampus tends to be smaller in people with BPD, as it is in people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, in BPD, unlike PTSD, the amygdala also tends to be smaller.[58] This unusually strong activity may explain the unusual strength and longevity of fear, sadness, anger, and shame experienced by people with BPD, as well as their heightened sensitivity to displays of these emotions in others.[58] Given its role in regulating emotional arousal, the relative inactivity of the prefrontal cortex might explain the difficulties people with BPD experience in regulating their emotions and responses to stress.[59]

Neurobiology

Borderline personality disorder has previously been strongly associated with the occurrence of childhood trauma. While many psychiatric diagnoses are believed to be associated with traumatic experiences occurring during critical periods of childhood, specific neurobiological factors have been identified within patients diagnosed with BPD. Dysregulations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and cortisol levels have been intensively studied in individuals who have experienced childhood traumas and have been formally diagnosed with BPD. The HPA axis functions to maintain homeostasis when the body is exposed to stressors but has been found to be dysregulated among individuals with a history of childhood abuse. When the body is exposed to stress, the hypothalamus, specifically the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) releases peptides arginine vasopressin (AVP) and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF). When these peptides travel through the body, they stimulate corticotrophic cells, resulting in the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH binds to receptors in the adrenal cortex, which stimulates the release of cortisol. Intracellular glucocorticoid receptor subtypes of mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and low-affinity type receptor (GR) have been found to mediate the effects of cortisol on different areas of the body. While MRs have high affinity for cortisol and are highly saturated in response to stress, GRs have low affinity for cortisol and bind cortisol at high concentrations when an individual is exposed to a stressor.[60] There have also been associations identified with FKBP5 polymorphisms, rs4713902 and rs9470079 in individuals with BPD. For those with BPD who have experienced childhood trauma, rs3798347-T and rs10947563-A have been associated, specifically in individuals with both BPD diagnosis and a history of childhood physical abuse and emotional neglect.[60]

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) regulates cortisol production, which is released in response to stress. Cortisol production tends to be elevated in people with BPD, indicating a hyperactive HPA axis in these individuals.[61] This causes them to experience a greater biological stress response, which might explain their greater vulnerability to irritability.[62] Since traumatic events can increase cortisol production and HPA axis activity, one possibility is that the prevalence of higher than average activity in the HPA axis of people with BPD may simply be a reflection of the higher than average prevalence of traumatic childhood and maturational events among people with BPD.[62]

Estrogen

Individual differences in women's estrogen cycles may be related to the expression of BPD symptoms in female patients.[63] A 2003 study found that women's BPD symptoms were predicted by changes in estrogen levels throughout their menstrual cycles, an effect that remained significant when the results were controlled for a general increase in negative affect.[64]

Childhood trauma

There is a strong correlation between child abuse, especially child sexual abuse, and development of BPD.[65][66][67] Many individuals with BPD report a history of abuse and neglect as young children, but causation is still debated.[68] Patients with BPD have been found to be significantly more likely to report having been verbally, emotionally, physically, or sexually abused by caregivers of either sex.[69] They also report a high incidence of incest and loss of caregivers in early childhood.[70] Individuals with BPD were also likely to report having caregivers of both sexes deny the validity of their thoughts and feelings. Caregivers were also reported to have failed to provide needed protection and to have neglected their child's physical care. Parents of both sexes were typically reported to have withdrawn from the child emotionally and to have treated the child inconsistently.[70] Additionally, women with BPD who reported a previous history of neglect by a female caregiver and abuse by a male caregiver were significantly more likely to have experienced sexual abuse by a non-caregiver.[70]

It has been suggested that children who experience chronic early maltreatment and attachment difficulties may go on to develop borderline personality disorder.[71] Writing in the psychoanalytic tradition, Otto Kernberg argues that a child's failure to achieve the developmental task of psychic clarification of self and other and failure to overcome splitting might increase the risk of developing a borderline personality.[72]

Neurological patterns

The intensity and reactivity of a person's negative affectivity, or tendency to feel negative emotions, predicts BPD symptoms more strongly than does childhood sexual abuse.[73] This finding, differences in brain structure (see Brain abnormalities), and the fact that some patients with BPD do not report a traumatic history[74] suggest that BPD is distinct from the post-traumatic stress disorder which frequently accompanies it. Thus, researchers examine developmental causes in addition to childhood trauma.

Research published in January 2013 by Anthony Ruocco at the University of Toronto has highlighted two patterns of brain activity that may underlie the dysregulation of emotion indicated in this disorder: (1) increased activity in the brain circuits responsible for the experience of heightened emotional pain, coupled with (2) reduced activation of the brain circuits that normally regulate or suppress these generated painful emotions. These two neural networks are seen to be dysfunctionally operative in the limbic system, but the specific regions vary widely in individuals, which calls for the analysis of more neuroimaging studies.[75]

Also (contrary to the results of earlier studies) sufferers of BPD showed less activation in the amygdala in situations of increased negative emotionality than the control group. John Krystal, editor of the journal Biological Psychiatry, wrote that these results "[added] to the impression that people with borderline personality disorder are 'set-up' by their brains to have stormy emotional lives, although not necessarily unhappy or unproductive lives".[75] Their emotional instability has been found to correlate with differences in several brain regions.[76]

Executive function

While high rejection sensitivity is associated with stronger symptoms of borderline personality disorder, executive function appears to mediate the relationship between rejection sensitivity and BPD symptoms.[77] That is, a group of cognitive processes that include planning, working memory, attention, and problem-solving might be the mechanism through which rejection sensitivity impacts BPD symptoms. A 2008 study found that the relationship between a person's rejection sensitivity and BPD symptoms was stronger when executive function was lower and that the relationship was weaker when executive function was higher.[77] This suggests that high executive function might help protect people with high rejection sensitivity against symptoms of BPD.[77] A 2012 study found that problems in working memory might contribute to greater impulsivity in people with BPD.[78]

Family environment

Family environment mediates the effect of child sexual abuse on the development of BPD. An unstable family environment predicts the development of the disorder, while a stable family environment predicts a lower risk. One possible explanation is that a stable environment buffers against its development.[79]

Self-complexity

Self-complexity, or considering one's self to have many different characteristics, may lessen the apparent discrepancy between an actual self and a desired self-image. Higher self-complexity may lead a person to desire more characteristics instead of better characteristics; if there is any belief that characteristics should have been acquired, these may be more likely to have been experienced as examples rather than considered as abstract qualities. The concept of a norm does not necessarily involve the description of the attributes that represent the norm: cognition of the norm may only involve the understanding of "being like", a concrete relation and not an attribute.[80]

Thought suppression

A 2005 study found that thought suppression, or conscious attempts to avoid thinking certain thoughts, mediates the relationship between emotional vulnerability and BPD symptoms.[73] A later study found that the relationship between emotional vulnerability and BPD symptoms is not necessarily mediated by thought suppression. However, this study did find that thought suppression mediates the relationship between an invalidating environment and BPD symptoms.[81]

Developmental theories

Marsha Linehan's biosocial developmental theory of borderline personality disorder suggests that BPD emerges from the combination of an emotionally vulnerable child, and an invalidating environment. Emotional vulnerability may consist of biological, inherited factors that affect a child's temperament. Invalidating environments may include contexts where a child's emotions and needs are neglected, ridiculed, dismissed, or discouraged, or may include contexts of trauma and abuse.

Linehan’s theory was modified by Sheila Crowell, who proposed that impulsivity also plays an important role in the development of BPD. Crowell found that children who are emotionally vulnerable and are exposed to invalidating environments are much more likely to develop BPD if they are also highly impulsive.[82] Both theories describe an interplay between a child’s inherited personality traits and their environment. For example, an emotionally sensitive or impulsive child may be difficult to parent, exacerbating the invalidating environment; conversely, invalidation can make an emotionally sensitive child more reactive and distressed.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of borderline personality disorder is based on a clinical assessment by a mental health professional. The best method is to present the criteria of the disorder to a person and to ask them if they feel that these characteristics accurately describe them.[13] Actively involving people with BPD in determining their diagnosis can help them become more willing to accept it.[13] Some clinicians prefer not to tell people with BPD what their diagnosis is, either from concern about the stigma attached to this condition or because BPD used to be considered untreatable; it is usually helpful for the person with BPD to know their diagnosis.[13] This helps them know that others have had similar experiences and can point them toward effective treatments.[13]

In general, the psychological evaluation includes asking the patient about the beginning and severity of symptoms, as well as other questions about how symptoms impact the patient's quality of life. Issues of particular note are suicidal ideations, experiences with self-harm, and thoughts about harming others.[83] Diagnosis is based both on the person's report of their symptoms and on the clinician's own observations.[83] Additional tests for BPD can include a physical exam and laboratory tests to rule out other possible triggers for symptoms, such as thyroid conditions or substance abuse.[83] The ICD-10 manual refers to the disorder as emotionally unstable personality disorder and has similar diagnostic criteria. In the DSM-5, the name of the disorder remains the same as in the previous editions.[5]

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition (DSM-5) has removed the multiaxial system. Consequently, all disorders, including personality disorders, are listed in Section II of the manual. A person must meet 5 of 9 criteria to receive a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder.[84] The DSM-5 defines the main features of BPD as a pervasive pattern of instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affect, as well as markedly impulsive behavior.[84] In addition, the DSM-5 proposes alternative diagnostic criteria for BPD in section III, "Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders". These alternative criteria are based on trait research and include specifying at least four of seven maladaptive traits.[85] According to Marsha Linehan, many mental health professionals find it challenging to diagnose BPD using the DSM criteria, since these criteria describe such a wide variety of behaviors.[86] To address this issue, Linehan has grouped the symptoms of BPD under five main areas of dysregulation: emotions, behavior, interpersonal relationships, sense of self, and cognition.[86]

International Classification of Disease

The World Health Organization's ICD-10 defines a disorder that is conceptually similar to BPD, called (F60.3) Emotionally unstable personality disorder. Its two subtypes are described below.[87]

F60.30 Impulsive type

At least three of the following must be present, one of which must be (2):

- marked tendency to act unexpectedly and without consideration of the consequences;

- marked tendency to engage in quarrelsome behavior and to have conflicts with others, especially when impulsive acts are thwarted or criticized;

- liability to outbursts of anger or violence, with inability to control the resulting behavioral explosions;

- difficulty in maintaining any course of action that offers no immediate reward;

- unstable and capricious (impulsive, whimsical) mood.

F60.31 Borderline type

At least three of the symptoms mentioned in F60.30 Impulsive type must be present [see above], with at least two of the following in addition:

- disturbances in and uncertainty about self-image, aims, and internal preferences;

- liability to become involved in intense and unstable relationships, often leading to emotional crisis;

- excessive efforts to avoid abandonment;

- recurrent threats or acts of self-harm;

- chronic feelings of emptiness;

- demonstrates impulsive behavior, e.g., speeding in a car or substance abuse.[88]

The ICD-10 also describes some general criteria that define what is considered a personality disorder.

Millon's subtypes

Theodore Millon has proposed four subtypes of BPD. He suggests that an individual diagnosed with BPD may exhibit none, one, or multiple of the following:[89]

| Subtype | Features |

|---|---|

| Discouraged borderline (including avoidant and dependent features) | Pliant, submissive, loyal, humble; feels vulnerable and in constant jeopardy; feels hopeless, depressed, helpless, and powerless. |

| Petulant borderline (including negativistic features) | Negativistic, impatient, restless, as well as stubborn, defiant, sullen, pessimistic, and resentful; easily feels "slighted" and quickly disillusioned. |

| Impulsive borderline (including histrionic or antisocial features) | Captivating, capricious, superficial, flighty, distractable, frenetic, and seductive; fearing loss, the individual becomes agitated; gloomy and irritable; and potentially suicidal. |

| Self-destructive borderline (including depressive or masochistic features) | Inward-turning, intropunitive (self-punishing), angry; conforming, deferential, and ingratiating behaviors have deteriorated; increasingly high-strung and moody; possible suicide. |

Misdiagnosis

People with BPD may be misdiagnosed for a variety of reasons. One reason for misdiagnosis is BPD has symptoms that coexist (comorbidity) with other disorders such as depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and bipolar disorder.[90][91]

Family members

People with BPD are prone to feeling angry at members of their family and alienated from them. On their part, family members often feel angry and helpless at how their BPD family members relate to them.[13] Parents of adults with BPD are often both over-involved and under-involved in family interactions.[92] In romantic relationships, BPD is linked to increased levels of chronic stress and conflict, decreased satisfaction of romantic partners, domestic abuse, and unwanted pregnancy. However, these links may apply to personality disorders in general.[28]

Adolescence

Onset of symptoms typically occurs during adolescence or young adulthood, although symptoms suggestive of this disorder can sometimes be observed in children.[93] Symptoms among adolescents that predict the development of BPD in adulthood may include problems with body-image, extreme sensitivity to rejection, behavioral problems, non-suicidal self-injury, attempts to find exclusive relationships, and severe shame.[13] Many adolescents experience these symptoms without going on to develop BPD, but those who experience them are 9 times as likely as their peers to develop BPD. They are also more likely to develop other forms of long-term social disabilities.[13]

BPD is recognised as a valid and stable diagnosis during adolescence.[94][95][96][97] The diagnosis of BPD (also described as "personality disorder: borderline pattern qualifier") in adolescents is supported in recent updates to the international diagnostic and psychiatric classification tools including the DSM-5 and ICD-11.[98][99][100] Early diagnosis of BPD has been recognised as instrumental to the early intervention and effective treatment for BPD in young people.[96][101][102] Accordingly, national treatment guidelines recommend the diagnosis and treatment of BPD among adolescents in many countries including Australia, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Switzerland.[103][104][105][106]

The diagnosis of BPD during adolescence has been controversial.[96][107][108] Early clinical guidelines encouraged caution when diagnosing BPD during adolescence.[109][110][111] Perceived barriers to the diagnosis of BPD during adolescence included concerns about the validity of a diagnosis in young people, the misdiagnosis normal adolescent behaviour as symptoms of BPD, the stigmatising effect of a diagnosis for adolescents, and whether personality during adolescence was sufficiently stable for a valid diagnosis of BPD.[96] Psychiatric research has since shown BPD to be a valid, stable and clinically useful diagnosis in adolescent populations.[94][95][96][97] However, ongoing misconceptions about the diagnosis of BPD in adolescence remain prevalent among mental health professionals.[112][113][114] Clinical reluctance to diagnose BPD as a key barrier to the provision of effective treatment in adolescent populations.[112][115][116]

A BPD diagnosis in adolescence might predict that the disorder will continue into adulthood.[109][117] Among individuals diagnosed with BPD during adolescence, there appears to be one group in which the disorder remains stable over time and another group in which the individuals move in and out of the diagnosis.[118] Earlier diagnoses may be helpful in creating a more effective treatment plan for the adolescent.[109][117] Family therapy is considered a helpful component of treatment for adolescents with BPD.[119]

Differential diagnosis and comorbidity

Lifetime comorbid (co-occurring) conditions are common in BPD. Compared to those diagnosed with other personality disorders, people with BPD showed a higher rate of also meeting criteria for[120]

- mood disorders, including major depression and bipolar disorder

- anxiety disorders, including panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- other personality disorders, including schizotypal, antisocial and dependent personality disorder

- substance abuse

- eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa and bulimia

- attention deficit hyperactivity disorder[121]

- somatic symptom disorders (formerly known as somatoform disorders: a category of mental disorders included in a number of diagnostic schemes of mental illness)

- dissociative disorders

A diagnosis of a personality disorder should not be made during an untreated mood episode/disorder, unless the lifetime history supports the presence of a personality disorder.

Comorbid Axis I disorders

| Axis I diagnosis | Overall (%) | Male (%) | Female (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mood disorders | 75.0 | 68.7 | 80.2 |

| Major depressive disorder | 32.1 | 27.2 | 36.1 |

| Dysthymia | 9.7 | 7.1 | 11.9 |

| Bipolar I disorder | 31.8 | 30.6 | 32.7 |

| Bipolar II disorder | 7.7 | 6.7 | 8.5 |

| Anxiety disorders | 74.2 | 66.1 | 81.1 |

| Panic disorder with agoraphobia | 11.5 | 7.7 | 14.6 |

| Panic disorder without agoraphobia | 18.8 | 16.2 | 20.9 |

| Social phobia | 29.3 | 25.2 | 32.7 |

| Specific phobia | 37.5 | 26.6 | 46.6 |

| PTSD | 39.2 | 29.5 | 47.2 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 35.1 | 27.3 | 41.6 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder** | 15.6 | --- | --- |

| Substance use disorders | 72.9 | 80.9 | 66.2 |

| Any alcohol use disorder | 57.3 | 71.2 | 45.6 |

| Any drug use disorder | 36.2 | 44.0 | 29.8 |

| Eating disorders** | 53.0 | 20.5 | 62.2 |

| Anorexia nervosa** | 20.8 | 7 * | 25 * |

| Bulimia nervosa** | 25.6 | 10 * | 30 * |

| Eating disorder not otherwise specified** | 26.1 | 10.8 | 30.4 |

| Somatoform disorders** | 10.3 | 10 * | 10 * |

| Somatization disorder** | 4.2 | --- | --- |

| Hypochondriasis** | 4.7 | --- | --- |

| Somatoform pain disorder** | 4.2 | --- | --- |

| Psychotic disorders** | 1.3 | 1 * | 1 * |

| * Approximate values ** Values from 1998 study[120] --- Value not provided by study | |||

A 2008 study found that at some point in their lives, 75% of people with BPD meet criteria for mood disorders, especially major depression and bipolar I, and nearly 75% meet criteria for an anxiety disorder.[122] Nearly 73% meet criteria for substance abuse or dependency, and about 40% for PTSD.[122] It is noteworthy that less than half of the participants with BPD in this study presented with PTSD, a prevalence similar to that reported in an earlier study.[120] The finding that less than half of patients with BPD experience PTSD during their lives challenges the theory that BPD and PTSD are the same disorder.[120]

There are marked sex differences in the types of comorbid conditions a person with BPD is likely to have[120] – a higher percentage of males with BPD meet criteria for substance-use disorders, while a higher percentage of females with BPD meet criteria for PTSD and eating disorders.[120][122][123] In one study, 38% of participants with BPD met the criteria for a diagnosis of ADHD.[121] In another study, 6 of 41 participants (15%) met the criteria for an autism spectrum disorder (a subgroup that had significantly more frequent suicide attempts).[124]

Regardless that it is an infradiagnosed disorder, a few studies have shown that the "lower expressions" of it might lead to wrong diagnoses. The many and shifting Axis I disorders in people with BPD can sometimes cause clinicians to miss the presence of the underlying personality disorder. However, since a complex pattern of Axis I diagnoses has been found to strongly predict the presence of BPD, clinicians can use the feature of a complex pattern of comorbidity as a clue that BPD might be present.[120]

Mood disorders

Many people with borderline personality disorder also have mood disorders, such as major depressive disorder or a bipolar disorder.[26] Some characteristics of BPD are similar to those of mood disorders, which can complicate the diagnosis.[125][126][127] It is especially common for people to be misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder when they have borderline personality disorder or vice versa.[128] For someone with bipolar disorder, behavior suggestive of BPD might appear while experiencing an episode of major depression or mania, only to disappear once mood has stabilized.[129] For this reason, it is ideal to wait until mood has stabilized before attempting to make a diagnosis.[129]

At face value, the affective lability of BPD and the rapid mood cycling of bipolar disorders can seem very similar.[130] It can be difficult even for experienced clinicians, if they are unfamiliar with BPD, to differentiate between the mood swings of these two conditions.[131] However, there are some clear differences.[128]

First, the mood swings of BPD and bipolar disorder tend to have different durations. In some people with bipolar disorder, episodes of depression or mania last for at least two weeks at a time, which is much longer than moods last in people with BPD.[128] Even among those who experience bipolar disorder with more rapid mood shifts, their moods usually last for days, while the moods of people with BPD can change in minutes or hours.[131] So while euphoria and impulsivity in someone with BPD might resemble a manic episode, the experience would be too brief to qualify as a manic episode.[129][131]

Second, the moods of bipolar disorder do not respond to changes in the environment, while the moods of BPD do respond to changes in the environment.[129] That is, a positive event would not lift the depressed mood caused by bipolar disorder, but a positive event would potentially lift the depressed mood of someone with BPD. Similarly, an undesirable event would not dampen the euphoria caused by bipolar disorder, but an undesirable event would dampen the euphoria of someone with borderline personality disorder.[129]

Third, when people with BPD experience euphoria, it is usually without the racing thoughts and decreased need for sleep that are typical of hypomania,[129] though a later 2013 study of data collected in 2004 found that borderline personality disorder diagnosis and symptoms were associated with chronic sleep disturbances, including difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and waking earlier than desired, as well as with the consequences of poor sleep, and noted that "[f]ew studies have examined the experience of chronic sleep disturbances in those with borderline personality disorder".[132]

Because the two conditions have a number of similar symptoms, BPD was once considered to be a mild form of bipolar disorder[133][134] or to exist on the bipolar spectrum. However, this would require that the underlying mechanism causing these symptoms be the same for both conditions. Differences in phenomenology, family history, longitudinal course, and responses to treatment suggest that this is not the case.[135] Researchers have found "only a modest association" between bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder, with "a strong spectrum relationship with [BPD and] bipolar disorder extremely unlikely".[136] Benazzi et al. suggest that the DSM-IV BPD diagnosis combines two unrelated characteristics: an affective instability dimension related to bipolar II and an impulsivity dimension not related to bipolar II.[137]

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) occurs in 3–8% of women.[138] Symptoms begin during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, and end during menstruation.[139] Symptoms may include marked mood swings, irritability, depressed mood, feeling hopeless or suicidal, a subjective sense of being overwhelmed or out of control, anxiety, binge eating, difficulty concentrating, and substantial impairment of interpersonal relationships.[140][141] People with PMDD typically begin to experience symptoms in their early twenties, although many do not seek treatment until their early thirties.[140]

Although some of the symptoms of PMDD and BPD are similar, they are different disorders. They are distinguishable by the timing and duration of symptoms, which are markedly different: the symptoms of PMDD occur only during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle,[140] whereas BPD symptoms occur persistently at all stages of the menstrual cycle. In addition, the symptoms of PMDD do not include impulsivity.[140]

Comorbid Axis II disorders

| Axis II diagnosis | Overall (%) | Male (%) | Female (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any cluster A | 50.4 | 49.5 | 51.1 |

| Paranoid | 21.3 | 16.5 | 25.4 |

| Schizoid | 12.4 | 11.1 | 13.5 |

| Schizotypal | 36.7 | 38.9 | 34.9 |

| Any other cluster B | 49.2 | 57.8 | 42.1 |

| Antisocial | 13.7 | 19.4 | 9.0 |

| Histrionic | 10.3 | 10.3 | 10.3 |

| Narcissistic | 38.9 | 47.0 | 32.2 |

| Any cluster C | 29.9 | 27.0 | 32.3 |

| Avoidant | 13.4 | 10.8 | 15.6 |

| Dependent | 3.1 | 2.6 | 3.5 |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 22.7 | 21.7 | 23.6 |

About three-fourths of people diagnosed with BPD also meet the criteria for another Axis II personality disorder at some point in their lives. (In a major 2008 study – see adjacent table – the rate was 73.9%.)[122] The Cluster A disorders, paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal, are broadly the most common. The Cluster as a whole affects about half, with schizotypal alone affecting one third.[122]

BPD is itself a Cluster B disorder. The other Cluster B disorders, antisocial, histrionic, and narcissistic, similarly affect about half of BPD patients (lifetime incidence), with again narcissistic affecting one third or more.[122] Cluster C, avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive, showed the least overlap, slightly under one third.[122]

Management

Psychotherapy is the primary treatment for borderline personality disorder.[7] Treatments should be based on the needs of the individual, rather than upon the general diagnosis of BPD. Medications are useful for treating comorbid disorders, such as depression and anxiety.[142] Short-term hospitalization has not been found to be more effective than community care for improving outcomes or long-term prevention of suicidal behavior in those with BPD.[143]

Psychotherapy

Long-term psychotherapy is currently the treatment of choice for BPD.[144] While psychotherapy, in particular dialectical behavior therapy and psychodynamic approaches, is effective, the effects are slow: many people have to put in years of work to be effective.[145]

More rigorous treatments are not substantially better than less rigorous treatments.[146] There are six such treatments available: dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy (DDP),[147] mentalization-based treatment (MBT), transference-focused psychotherapy, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), general psychiatric management, and schema-focused therapy.[13] While DBT is the therapy that has been studied the most,[148] all these treatments appear effective for treating BPD, except for schema-focused therapy.[13] Long-term therapy of any kind, including schema-focused therapy, is better than no treatment, especially in reducing urges to self-injure.[144]

Transference-focused therapy aims to break away from absolute thinking. In this, it gets the people to articulate their social interpretations and their emotions in order to turn their views into less rigid categories. The therapist addresses the individual's feelings and goes over situations, real or realistic, that could happen as well as how to approach them.[149]

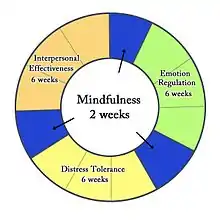

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) has similar components to CBT, adding in practices such as meditation. In doing this, it helps the individual with BPD gain skills to manage symptoms. These skills include emotion regulation, mindfulness, and stress hardiness.[149] Since those diagnosed with BPD have such intense emotions, learning to regulate them is a huge step in the therapeutic process. Some components of DBT are working long-term with patients, building skills to understand and regulate emotions, homework assignments, and strong availability of therapist to their client. [150] Patients with borderline personality disorder also must take time in DBT to work with their therapist to learn how to get through situations surrounded by intense emotions or stress as well as learning how to better their interpersonal relationships.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is also a type of psychotherapy used for treatment of BPD. This type of therapy relies on changing people's behaviors and beliefs by identifying problems from the disorder. CBT is known to reduce some anxiety and mood symptoms as well as reduce suicidal thoughts and self-harming behaviors.[4]

Mentalization-based therapy and transference-focused psychotherapy are based on psychodynamic principles, and dialectical behavior therapy is based on cognitive-behavioral principles and mindfulness.[144] General psychiatric management combines the core principles from each of these treatments, and it is considered easier to learn and less intensive.[13] Randomized controlled trials have shown that DBT and MBT may be the most effective, and the two share many similarities.[151][152] Researchers are interested in developing shorter versions of these therapies to increase accessibility, to relieve the financial burden on patients, and to relieve the resource burden on treatment providers.[144][152]

Some research indicates that mindfulness meditation may bring about favorable structural changes in the brain, including changes in brain structures that are associated with BPD.[153][154][155] Mindfulness-based interventions also appear to bring about an improvement in symptoms characteristic of BPD, and some clients who underwent mindfulness-based treatment no longer met a minimum of five of the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for BPD.[155][156]

Medications

A 2010 review by the Cochrane collaboration found that no medications show promise for "the core BPD symptoms of chronic feelings of emptiness, identity disturbance, and abandonment". However, the authors found that some medications may impact isolated symptoms associated with BPD or the symptoms of comorbid conditions.[157] A 2017 review examined evidence published since the 2010 Cochrane review and found that "evidence of effectiveness of medication for BPD remains very mixed and is still highly compromised by suboptimal study design".[158]

Of the typical antipsychotics studied in relation to BPD, haloperidol may reduce anger and flupenthixol may reduce the likelihood of suicidal behavior. Among the atypical antipsychotics, one trial found that aripiprazole may reduce interpersonal problems and impulsivity.[157] Olanzapine, as well as quetiapine, may decrease affective instability, anger, psychotic paranoid symptoms, and anxiety, but a placebo had a greater benefit on suicidal ideation than olanzapine did. The effect of ziprasidone was not significant.[157][158]

Of the mood stabilizers studied, valproate semisodium may ameliorate depression, impulsivity, interpersonal problems, and anger. Lamotrigine may reduce impulsivity and anger; topiramate may ameliorate interpersonal problems, impulsivity, anxiety, anger, and general psychiatric pathology. The effect of carbamazepine was not significant. Of the antidepressants, amitriptyline may reduce depression, but mianserin, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and phenelzine sulfate showed no effect. Omega-3 fatty acid may ameliorate suicidality and improve depression. As of 2017, trials with these medications had not been replicated and the effect of long-term use had not been assessed.[157][158]

Because of weak evidence and the potential for serious side effects from some of these medications, the United Kingdom (UK) National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2009 clinical guideline for the treatment and management of BPD recommends, "Drug treatment should not be used specifically for borderline personality disorder or for the individual symptoms or behavior associated with the disorder." However, "drug treatment may be considered in the overall treatment of comorbid conditions". They suggest a "review of the treatment of people with borderline personality disorder who do not have a diagnosed comorbid mental or physical illness and who are currently being prescribed drugs, with the aim of reducing and stopping unnecessary drug treatment".[159]

Services

There is a significant difference between the number of those who would benefit from treatment and the number of those who are treated. The so-called "treatment gap" is a function of the disinclination of the afflicted to submit for treatment, an underdiagnosing of the disorder by healthcare providers, and the limited availability and access to state-of-the-art treatments.[160] Nonetheless, individuals with BPD accounted for about 20% of psychiatric hospitalizations in one survey.[161] The majority of individuals with BPD who are in treatment continue to use outpatient treatment in a sustained manner for several years, but the number using the more restrictive and costly forms of treatment, such as inpatient admission, declines with time.[162]

Experience of services varies.[163] Assessing suicide risk can be a challenge for clinicians, and patients themselves tend to underestimate the lethality of self-injurious behaviors. People with BPD typically have a chronically elevated risk of suicide much above that of the general population and a history of multiple attempts when in crisis.[164] Approximately half the individuals who commit suicide meet criteria for a personality disorder. Borderline personality disorder remains the most commonly associated personality disorder with suicide.[165]

After a patient suffering from BPD died, The National Health Service (NHS) in England was criticized by a coroner in 2014 for the lack of commissioned services to support those with BPD. Evidence was given that 45% of female patients had BPD and there was no provision or priority for therapeutic psychological services. At the time, there were only a total of 60 specialized inpatient beds in England, all of them located in London or the northeast region.[166]

Prognosis

With treatment, the majority of people with BPD can find relief from distressing symptoms and achieve remission, defined as a consistent relief from symptoms for at least two years.[167][168] A longitudinal study tracking the symptoms of people with BPD found that 34.5% achieved remission within two years from the beginning of the study. Within four years, 49.4% had achieved remission, and within six years, 68.6% had achieved remission. By the end of the study, 73.5% of participants were found to be in remission.[167] Moreover, of those who achieved recovery from symptoms, only 5.9% experienced recurrences. A later study found that ten years from baseline (during a hospitalization), 86% of patients had sustained a stable recovery from symptoms.[169]

Patient personality can play an important role during the therapeutic process, leading to better clinical outcomes. Recent research has shown that BPD patients undergoing dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) exhibit better clinical outcomes correlated with higher levels of the trait of agreeableness in the patient, compared to patients either low in agreeableness or not being treated with DBT. This association was mediated through the strength of a working alliance between patient and therapist; that is, more agreeable patients developed stronger working alliances with their therapists, which in turn, led to better clinical outcomes.[170]

In addition to recovering from distressing symptoms, people with BPD also achieve high levels of psychosocial functioning. A longitudinal study tracking the social and work abilities of participants with BPD found that six years after diagnosis, 56% of participants had good function in work and social environments, compared to 26% of participants when they were first diagnosed. Vocational achievement was generally more limited, even compared to those with other personality disorders. However, those whose symptoms had remitted were significantly more likely to have good relationships with a romantic partner and at least one parent, good performance at work and school, a sustained work and school history, and good psychosocial functioning overall.[171]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of BPD was initially estimated to be 1–2% of the general population[168] and to occur three times more often in women than in men.[172][173] However, the lifetime prevalence of BPD, as defined in the DSM-IV, in a 2008 study was found to be 5.9% of the American population, occurring in 5.6% of men and 6.2% of women.[122] The difference in rates between men and women in this study was not found to be statistically significant.[122]

Borderline personality disorder is estimated to contribute to 20% of psychiatric hospitalizations and to occur among 10% of outpatients.[174]

29.5% of new inmates in the U.S. state of Iowa fit a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder in 2007,[175] and the overall prevalence of BPD in the U.S. prison population is thought to be 17%.[174] These high numbers may be related to the high frequency of substance abuse and substance use disorders among people with BPD, which is estimated at 38%.[174]

History

The coexistence of intense, divergent moods within an individual was recognized by Homer, Hippocrates, and Aretaeus, the latter describing the vacillating presence of impulsive anger, melancholia, and mania within a single person. The concept was revived by Swiss physician Théophile Bonet in 1684 who, using the term folie maniaco-mélancolique,[178] described the phenomenon of unstable moods that followed an unpredictable course. Other writers noted the same pattern, including the American psychiatrist Charles H. Hughes in 1884 and J. C. Rosse in 1890, who called the disorder "borderline insanity".[179] In 1921, Kraepelin identified an "excitable personality" that closely parallels the borderline features outlined in the current concept of BPD.[180]

The first significant psychoanalytic work to use the term "borderline" was written by Adolf Stern in 1938.[181][182] It described a group of patients suffering from what he thought to be a mild form of schizophrenia, on the borderline between neurosis and psychosis.

The 1960s and 1970s saw a shift from thinking of the condition as borderline schizophrenia to thinking of it as a borderline affective disorder (mood disorder), on the fringes of bipolar disorder, cyclothymia, and dysthymia. In the DSM-II, stressing the intensity and variability of moods, it was called cyclothymic personality (affective personality).[109] While the term "borderline" was evolving to refer to a distinct category of disorder, psychoanalysts such as Otto Kernberg were using it to refer to a broad spectrum of issues, describing an intermediate level of personality organization[180] between neurosis and psychosis.[183]

After standardized criteria were developed[184] to distinguish it from mood disorders and other Axis I disorders, BPD became a personality disorder diagnosis in 1980 with the publication of the DSM-III.[168] The diagnosis was distinguished from sub-syndromal schizophrenia, which was termed "schizotypal personality disorder".[183] The DSM-IV Axis II Work Group of the American Psychiatric Association finally decided on the name "borderline personality disorder", which is still in use by the DSM-5 today.[5] However, the term "borderline" has been described as uniquely inadequate for describing the symptoms characteristic of this disorder.[185]

Etymology

Earlier versions of the DSM, prior to the multiaxial diagnosis system, classified most people with mental health problems into two categories, the psychotics and the neurotics. Clinicians noted a certain class of neurotics who, when in crisis, appeared to straddle the borderline into psychosis.[186] The term "borderline personality disorder" was coined in American psychiatry in the 1960s. It became the preferred term over a number of competing names, such as "emotionally unstable character disorder" and "borderline schizophrenia" during the 1970s.[187][188] Borderline personality disorder was included in DSM-III (1980) despite not being universally recognized as a valid diagnosis.[189]

Controversies

Credibility and validity of testimony

The credibility of individuals with personality disorders has been questioned at least since the 1960s.[190]:2 Two concerns are the incidence of dissociation episodes among people with BPD and the belief that lying is a key component of this condition.

Dissociation

Researchers disagree about whether dissociation, or a sense of detachment from emotions and physical experiences, impacts the ability of people with BPD to recall the specifics of past events. A 1999 study reported that the specificity of autobiographical memory was decreased in BPD patients.[191] The researchers found that decreased ability to recall specifics was correlated with patients' levels of dissociation.[191]

Lying as a feature

Some theorists argue that patients with BPD often lie.[192] However, others write that they have rarely seen lying among patients with BPD in clinical practice.[192]

Gender

Since BPD can be a stigmatizing diagnosis even within the mental health community, some survivors of childhood abuse who are diagnosed with BPD are re-traumatized by the negative responses they receive from healthcare providers.[193] One camp argues that it would be better to diagnose these men or women with post-traumatic stress disorder, as this would acknowledge the impact of abuse on their behavior. Critics of the PTSD diagnosis argue that it medicalizes abuse rather than addressing the root causes in society.[194] Regardless, a diagnosis of PTSD does not encompass all aspects of the disorder (see brain abnormalities and terminology).

Joel Paris states that "In the clinic ... Up to 80% of patients are women. That may not be true in the community."[195] He offers the following explanations regarding these sex discrepancies:

The most probable explanation for gender differences in clinical samples is that women are more likely to develop the kind of symptoms that bring patients in for treatment. Twice as many women as men in the community suffer from depression (Weissman & Klerman, 1985). In contrast, there is a preponderance of men meeting criteria for substance abuse and psychopathy (Robins & Regier, 1991), and males with these disorders do not necessarily present in the mental health system. Men and women with similar psychological problems may express distress differently. Men tend to drink more and carry out more crimes. Women tend to turn their anger on themselves, leading to depression as well as the cutting and overdosing that characterize BPD. Thus, anti-social personality disorder (ASPD) and borderline personality disorders might derive from similar underlying pathology but present with symptoms strongly influenced by gender (Paris, 1997a; Looper & Paris, 2000). We have even more specific evidence that men with BPD may not seek help. In a study of completed suicides among people aged 18 to 35 years (Lesage et al., 1994), 30% of the suicides involved individuals with BPD (as confirmed by psychological autopsy, in which symptoms were assessed by interviews with family members). Most of the suicide completers were men, and very few were in treatment. Similar findings emerged from a later study conducted by our own research group (McGirr, Paris, Lesage, Renaud, & Turecki, 2007).[35]

In short, men are less likely to seek or accept appropriate treatment, more likely to be treated for symptoms of BPD such as substance abuse rather than BPD itself (the symptoms of BPD and ASPD possibly deriving from a similar underlying etiology), possibly more likely to wind up in the correctional system due to criminal behavior, and possibly more likely to commit suicide prior to diagnosis.

Among men diagnosed with BPD there is also evidence of a higher suicide rate: "men are more than twice as likely as women—18 percent versus 8 percent"—to die by suicide.[34]

There are also sex differences in borderline personality disorders.[196] Men with BPD are more likely to abuse substances, have explosive temper, high levels of novelty seeking and have anti-social, narcissistic, passive-aggressive or sadistic personality traits.[196] Women with BPD are more likely to have eating disorders, mood disorders, anxiety and post-traumatic stress.[196]

Manipulative behavior

Manipulative behavior to obtain nurturance is considered by the DSM-IV-TR and many mental health professionals to be a defining characteristic of borderline personality disorder.[197] However, Marsha Linehan notes that doing so relies upon the assumption that people with BPD who communicate intense pain, or who engage in self-harm and suicidal behavior, do so with the intention of influencing the behavior of others.[198] The impact of such behavior on others—often an intense emotional reaction in concerned friends, family members, and therapists—is thus assumed to have been the person's intention.[198]

However, their frequent expressions of intense pain, self-harming, or suicidal behavior may instead represent a method of mood regulation or an escape mechanism from situations that feel unbearable.[199]

Stigma

The features of BPD include emotional instability; intense, unstable interpersonal relationships; a need for intimacy; and a fear of rejection. As a result, people with BPD often evoke intense emotions in those around them. Pejorative terms to describe people with BPD, such as "difficult", "treatment resistant", "manipulative", "demanding", and "attention seeking", are often used and may become a self-fulfilling prophecy, as the negative treatment of these individuals triggers further self-destructive behavior.[200]

Physical violence

The stigma surrounding borderline personality disorder includes the belief that people with BPD are prone to violence toward others.[201] While movies and visual media often sensationalize people with BPD by portraying them as violent, the majority of researchers agree that people with BPD are unlikely to physically harm others.[201] Although people with BPD often struggle with experiences of intense anger, a defining characteristic of BPD is that they direct it inward toward themselves.[202] One of the key differences between BPD and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) is that people with BPD tend to internalize anger by hurting themselves, while people with ASPD tend to externalize it by hurting others.[202]

In addition, adults with BPD have often experienced abuse in childhood, so many people with BPD adopt a "no-tolerance" policy toward expressions of anger of any kind.[202] Their extreme aversion to violence can cause many people with BPD to overcompensate and experience difficulties being assertive and expressing their needs.[202] This is one way in which people with BPD choose to harm themselves over potentially causing harm to others.[202] Another way in which people with BPD avoid expressing their anger through violence is by causing physical damage to themselves, such as engaging in non-suicidal self-injury.[20][201]

Mental health care providers

People with BPD are considered to be among the most challenging groups of patients to work with in therapy, requiring a high level of skill and training for the psychiatrists, therapists, and nurses involved in their treatment.[203] A majority of psychiatric staff report finding individuals with BPD moderately to extremely difficult to work with and more difficult than other client groups.[204] This largely negative view of BPD can result in people with BPD being terminated from treatment early, being provided harmful treatment, not being informed of their diagnosis of BPD, or being misdiagnosed.[205] With healthcare providers contributing to the stigma of a BPD diagnosis, seeking treatment can often result in the perpetuation of BPD features. [205] Efforts are ongoing to improve public and staff attitudes toward people with BPD.[206][207]

In psychoanalytic theory, the stigmatization among mental health care providers may be thought to reflect countertransference (when a therapist projects his or her own feelings on to a client). Thus, a diagnosis of BPD often says more about the clinician's negative reaction to the patient than it does about the patient and explains away the breakdown in empathy between the therapist and the patient and becomes an institutional epithet in the guise of pseudoscientific jargon.[183] This inadvertent countertransference can give rise to inappropriate clinical responses, including excessive use of medication, inappropriate mothering, and punitive use of limit setting and interpretation.[208]

Some clients feel the diagnosis is helpful, allowing them to understand that they are not alone and to connect with others with BPD who have developed helpful coping mechanisms. However, others experience the term "borderline personality disorder" as a pejorative label rather than an informative diagnosis. They report concerns that their self-destructive behavior is incorrectly perceived as manipulative and that the stigma surrounding this disorder limits their access to health care.[209] Indeed, mental health professionals frequently refuse to provide services to those who have received a BPD diagnosis.[210]

Terminology

Because of concerns around stigma, and because of a move away from the original theoretical basis for the term (see history), there is ongoing debate about renaming borderline personality disorder. While some clinicians agree with the current name, others argue that it should be changed,[211] since many who are labelled with borderline personality disorder find the name unhelpful, stigmatizing, or inaccurate.[211][212] Valerie Porr, president of Treatment and Research Advancement Association for Personality Disorders states that "the name BPD is confusing, imparts no relevant or descriptive information, and reinforces existing stigma".[213]

Alternative suggestions for names include emotional regulation disorder or emotional dysregulation disorder. Impulse disorder and interpersonal regulatory disorder are other valid alternatives, according to John G. Gunderson of McLean Hospital in the United States.[214] Another term suggested by psychiatrist Carolyn Quadrio is post traumatic personality disorganization (PTPD), reflecting the condition's status as (often) both a form of chronic post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as a personality disorder.[67] However, although many with BPD do have traumatic histories, some do not report any kind of traumatic event, which suggests that BPD is not necessarily a trauma spectrum disorder.[74]

The Treatment and Research Advancements National Association for Personality Disorders (TARA-APD) campaigned unsuccessfully to change the name and designation of BPD in DSM-5, published in May 2013, in which the name "borderline personality disorder" remains unchanged and it is not considered a trauma- and stressor-related disorder.[215]

Society and culture

Fiction

Films and television shows have portrayed characters either explicitly diagnosed with or exhibiting traits suggestive of BPD. These may be misleading if they are thought to depict this disorder accurately.[201] The majority of researchers agree that in reality, people with BPD are unlikely to physically harm others, but rather most likely to harm themselves.[201]

Robert O. Friedel has suggested that the behavior of Theresa Dunn, the leading character of Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1975) is consistent with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder.[216]

The films Play Misty for Me (1971)[217] and Girl, Interrupted (1999, based on the memoir of the same name) both suggest the emotional instability of the disorder.[218] The film Single White Female (1992), like the first example, also suggests characteristics, some of which are actually atypical of the disorder: the character Hedy had markedly disturbed sense of identity and reacts drastically to abandonment.[217]:235 In a review of the film Shame (2011) for the British journal The Art of Psychiatry, another psychiatrist, Abby Seltzer, praises Carey Mulligan's portrayal of a character with the disorder even though it is never mentioned onscreen.[219]

Films attempting to depict characters with the disorder include A Thin Line Between Love and Hate (1996), Filth (2013), Fatal Attraction (1987), The Crush (1993), Mad Love (1995), Malicious (1995), Interiors (1978), The Cable Guy (1996), Mr. Nobody (2009), Moksha (2001), Margot at the Wedding (2007), Cracks (2009),[220] and Welcome to Me (2014).[221][222] Psychiatrists Eric Bui and Rachel Rodgers argue that the Anakin Skywalker/Darth Vader character in the Star Wars films meets six of the nine diagnostic criteria; Bui also found Anakin a useful example to explain BPD to medical students. In particular, Bui points to the character's abandonment issues, uncertainty over his identity, and dissociative episodes.[223]

On television, The CW show Crazy Ex-Girlfriend portrays a main character with borderline personality disorder,[224] and Emma Stone's character in the Netflix miniseries Maniac is diagnosed with the disorder.[225] Additionally, incestuous twins Cersei and Jaime Lannister, in George R. R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire series and its television adaptation, Game of Thrones, have traits of borderline and narcissistic personality disorders.[226]

Awareness

In early 2008, the United States House of Representatives declared the month of May Borderline Personality Disorder Awareness Month.[227][228]

In 2020, South Korean singer-songwriter Lee Sunmi spoke out about her struggle with borderline personality disorder on the show Running Mates, having been diagnosed 5 years prior. [229]

References

- Cloninger RC (2005). "Antisocial Personality Disorder: A Review". In Maj M, Akiskal HS, Mezzich JE (eds.). Personality disorders. New York City: John Wiley & Sons. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-470-09036-7. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Blom JD (2010). A dictionary of hallucinations (1st ed.). New York: Springer. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4419-1223-7. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Edvard Munch : the life of a person with borderline personality as seen through his art. [Danmark]: Lundbeck Pharma A/S. 1990. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-8798352419.

- "Borderline Personality Disorder". NIMH. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5 (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. pp. 645, 663–6. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Borderline Personality Disorder. Melbourne: National Health and Medical Research Council. 2013. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-1-86496-564-3.

In addition to the evidence identified by the systematic review, the Committee also considered a recent narrative review of studies that have evaluated biological and environmental factors as potential risk factors for BPD (including prospective studies of children and adolescents, and studies of young people with BPD)

- Leichsenring F, Leibing E, Kruse J, New AS, Leweke F (January 2011). "Borderline personality disorder". Lancet. 377 (9759): 74–84. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61422-5. PMID 21195251. S2CID 17051114.

- "Borderline Personality Disorder Differential Diagnoses". emedicine.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Borderline personality disorder NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 78. British Psychological Society. 2009. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Chapman AL (August 2019). "Borderline personality disorder and emotion dysregulation". Development and Psychopathology. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 31 (3): 1143–1156. doi:10.1017/S0954579419000658. ISSN 0954-5794. PMID 31169118. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Aviram RB, Brodsky BS, Stanley B (2006). "Borderline personality disorder, stigma, and treatment implications". Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 14 (5): 249–56. doi:10.1080/10673220600975121. PMID 16990170. S2CID 23923078.

- "Diagnostic criteria for 301.83 Borderline Personality Disorder – Behavenet". behavenet.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.