Battle of Droop Mountain

The Battle of Droop Mountain occurred in Pocahontas County, West Virginia, on November 6, 1863, during the American Civil War. A Union brigade commanded by Brigadier General William W. Averell defeated a smaller Confederate force commanded by Brigadier General John Echols and Colonel William L. "Mudwall" Jackson. Confederate forces were driven from their breastworks on Droop Mountain, losing weapons and equipment. They escaped southward through Lewisburg, West Virginia; hours before a second Union force commanded by Brigadier General Alfred N. Duffié occupied the town.

| Battle of Droop Mountain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Pocahontas County, West Virginia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~ 3,855 | ~ 1,700 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 140 (45 killed, 93 wounded, 2 captured) | 276 (33 killed, 121 wounded, 122 missing) | ||||||

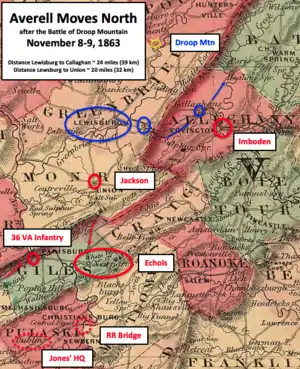

The Battle of Droop Mountain was one of the largest engagements in West Virginia during the war. Although Averell had a sound victory at Droop Mountain, he did not achieve his objectives of eliminating the Confederate Army in Lewisburg and damaging the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. The pro-Confederate community of Lewisburg was captured, but the Confederate Army escaped and returned weeks later. No serious attempt was made to attack the railroad. After the expedition, Averell moved north to near the West Virginia-Maryland border, and Duffié moved back toward Charleston.

Some historians claim the battle ended organized Confederate resistance in West Virginia. Post battle, most of the region's fighting shifted east to the Shenandoah Valley and West Virginia's eastern panhandle region. Other historians believe that the battle was a tactical victory for Echols and Jackson, since Averell did not eliminate the Confederate Army in Lewisburg; and more importantly, did not disturb the railroad.

Background and plans

On April 17, 1861, representatives of the Commonwealth of Virginia held the Virginia Secession Convention, and passed an Ordinance of Secession that declared secession from the United States. The ordinance was ratified by popular referendum on May 23, and Virginia later joined the Confederate States of America.[1] Many people in the northwestern portion of the state preferred to remain loyal to the United States, and delegates from that portion of the state met in June at the Second Wheeling Convention. On June 19, they approved a plan to establish an alternative loyal state government that would be located in Wheeling.[1] Although loyal Virginians approved their own statehood on October 24, 1861, West Virginia did not become a state in the United States until June 20, 1863.[2] After the creation of West Virginia, regular Confederate Army soldiers still operated within the state. Residents of the new state were not all loyal to the union, and the state continued to be plagued by bushwhackers and Partisan rangers practicing guerrilla warfare.[3] Historians estimate that residents of West Virginia provided 20,000 to 22,000 soldiers to each side in the American Civil War.[4] Lewisburg, located in West Virginia near the border with Virginia, was one of the communities that supported the Confederacy.[Note 1] Five skirmishes occurred at Lewisburg during the war, plus a small battle in 1862 and the town's capture and brief occupation in 1863.[6][7]

The new state had rugged terrain, few good roads, few settlements, and its people were poor.[8] One important asset for the Union Army was the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (a.k.a. B&O Railroad), which had rail line in the northern part of the West Virginia that was often targeted by the Confederate Army and its sympathizers.[9] Army resources were needed for the railroad's protection.[10] Union army leaders normally considered troops in West Virginia to be a defensive force that should handle Confederate raids and confront guerrillas and bushwhackers. Troops were typically scattered in small detachments.[8]

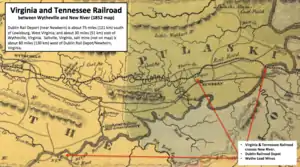

A significant portion of the fighting in West Virginia was related to railroads.[11] While the Union had an important railroad in the northern part of West Virginia; the Confederacy had the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, which was located in Virginia close to West Virginia's southern border. This railroad was used by the Confederacy for moving troops and supplies between those states, and connected to more railroads at Lynchburg, Virginia and Bristol, Tennessee.[12] It also had telegraph wires along its line, and important salt and lead mines were located along its route near Wytheville, Virginia.[13] The lead mine was the source for an estimated one third of the lead used by the Confederacy to produce bullets for its armies.[14] Multiple raids on the railroad originated from West Virginia.[12] A mid-July 1863 raid by Union cavalry and mounted infantry, known as the Wytheville Raid or Toland's Raid, failed to inflict permanent damage to the railroad and did not reach the mines.[15] An August 1863 planned raid of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad ended when Brigadier General William W. Averell was "handsomely repulsed" by a brigade commanded by Colonel George S. Patton in the Battle of White Sulphur Springs.[16]

Kelley's orders

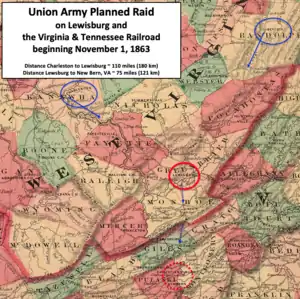

Brigadier General Benjamin Franklin Kelley was commander of the Union Army's Department of West Virginia. Kelley reported to General-in-Chief Henry Halleck. Through his chief-of-staff, Brigadier General George W. Cullum, Halleck let Kelley know that he wanted the Confederates out of Lewisburg and the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad disabled.[17][18] On October 23, 1863, Kelley ordered Averell to move his command south from Beverly, West Virginia, and attack a Confederate force stationed near Lewisburg in Greenbrier County, West Virginia. Droop Mountain was not part of the plan. The objective was to capture, or drive away, Confederate forces at or near Lewisburg.[17] A second Union force, which was from Brigadier General Eliakim P. Scammon's Third Division, would move southeast from Charleston to meet Averell in Lewisburg and provide assistance. The Charleston force would consist of two regiments of infantry and two regiments of cavalry, plus artillery.[17]

After Lewisburg, Averell was to attack the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad if practicable. Union infantry that was not mounted would remain in Lewisburg while mounted troops (cavalry and mounted infantry, including Duffié's) would proceed further south to Monroe County and cross into Virginia. Their objective was to destroy the railroad bridge over the New River, which was less than 10 miles (16 km) from the railroad's Dublin Station near Newbern, Virginia.[19] One historian considers the destruction of the railroad bridge and line to be the principal goal of Averell's expedition. At the time, Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet was in Tennessee with two divisions of the Army of Northern Virginia—serious damage to the railroad would disrupt his ability to communicate with army leadership and make it difficult to return his troops to the east.[20] If Averell determined that an attack on the railroad bridge was impracticable; he was to send his infantry and one battery back to Beverly. The remaining portion of his command would move to New Creek and get resupplied.[17] New Creek, originally known as Paddytown and later as Keyser, was a stop on the B&O Railroad near the West Virginia–Maryland border.[21] With no attack on the railroad, Duffié's command would hold Lewisburg or fall back to Meadow Bluff, West Virginia.[17]

Opposing forces

Confederate army

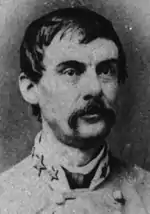

In November 1863, the Confederate Army controlled much of the Greenbrier Valley in West Virginia.[22] Confederate Major General Sam Jones commanded the Department of Western Virginia and East Tennessee, and his headquarters were about 75 miles (121 km) south of Lewisburg, West Virginia, at the Dublin Rail Depot for the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad in Virginia. Although Jones did not participate directly in the battle, the men and territory were his responsibility, as were the railroad and bridge near his headquarters that were targeted by the Union.[23][Note 2] He was in eastern Tennessee when Averell began his expedition, and returned to Dublin around November 6.[27] Brigadier General John Echols commanded a brigade that was headquartered in Lewisburg, and Colonel William L. "Mudwall" Jackson had a small cavalry brigade that patrolled in the Huntersville-Hillsboro region of West Virginia.[28][29][30] Further east, Brigadier General John D. Imboden commanded the Shenandoah Valley District.[31] Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins, who was a Cabell County, West Virginia native, was recovering from a wound received at the Battle of Gettysburg—but two regiments and a battery from his brigade were detached in the Greenbrier County area of West Virginia. Colonel Milton J. Ferguson temporarily commanded Jenkins' brigade.[32]

Union army—Averell

Beginning Union Army commander Kelley's plan, Averell's 4th Separate Brigade departed from Beverly on November 1, 1863. Many of his men were already familiar with the territory and opposition because they had been defeated a few months earlier during August in the Battle of White Sulphur Springs.[33] The brigade consisted of two infantry regiments, three mounted infantry regiments, one cavalry regiment, a portion of an independent cavalry battalion, two light batteries, and a signal corps detachment. The two infantry regiments were the 10th West Virginia and the 28th Ohio, while the mounted infantry regiments were the 2nd West Virginia, 3rd West Virginia, and 8th West Virginia.[34] The infantry was often led by Colonel Augustus Moor, and Colonel John H. Oley usually led the mounted infantry.[35][36] Moor was a veteran of Florida's Second Seminole War, and colonel of his regiment in the Mexican–American War.[37] Averell's cavalry was the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment and a battalion of six companies from West Virginia, Illinois, and Ohio. The cavalry was led by Colonel James M. Schoonmaker, and was armed with carbines.[38] The infantry, mounted or not, had muzzle-loader Enfield muskets.[39] Based on earlier reports, Averell's brigade had a maximum of 3,855 officers and men present for duty.[39][Note 3]

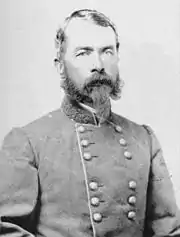

Union army—Duffié

.jpg.webp)

The mounted portion of Scammon's force, commanded by Brigadier General Alfred N. Duffié, departed from Charleston for Lewisburg on November 3. It numbered 970 officers and men with 1,025 horses, and initially consisted of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry Regiment, the 34th Ohio Mounted Infantry Regiment, and Simmonds' Battery.[40] Most of the men were familiar with Lewisburg, which was about 110 miles (180 km) away—one soldier from the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry described this excursion as the "Third Expedition to Lewisburg".[41] Both regiments were involved in a July 1863 raid on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, where they captured the town of Wytheville but inflicted little permanent damage to the railroad—and lost both of their colonels.[42][43] On November 4, after crossing the Gauley River at Gauley Bridge, Duffié was delayed by blockades in the road that were so numerous that a new road had to be dug around them in some instances.[41] Two infantry regiments, commanded by Colonel Carr B. White, joined Duffié's mounted men on November 5 at Tyree's Tavern in Fayette County.[44]

Initial movements

Contact

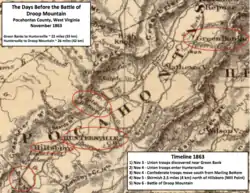

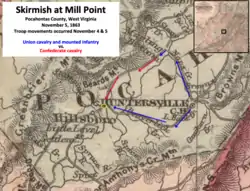

In the first few days of the expedition, Averell's Brigade traveled south over the most direct route, and encountered a few bands of guerrillas and small detachments of Confederate Army soldiers.[17] They reached the summit of Cheat Mountain at noon on November 2, and camped that evening in the Greenbrier Valley in Pocahontas County.[45] On November 3, a squadron of the 8th West Virginia Mounted Infantry, which Averell had sent on a different route, was discovered near Green Bank, by a detachment of about 350 men from the 19th Virginia Cavalry Regiment commanded by Lieutenant George W. Siple. After a small clash, the squadron of West Virginians continued south and reunited with Averell's main force near Green Bank and Arbovale, which was about 20 miles (32 km) north of Huntersville.[46]

Siple reported the encounter to Colonel Jackson, who was headquartered with the main body of the 19th Virginia Cavalry just northwest of Hillsboro in Mill Point.[46] Jackson warned Colonel William W. Arnett, who was 8 miles (13 km) north with the 20th Virginia Cavalry Regiment near the Greenbrier River in Marling Bottom.[Note 4] Jackson also sent the news to nearby detachments and Brigadier General John Echols in Lewisburg.[46] Siple's detachment became cut-off and did not rejoin the 19th Virginia Cavalry until days later—depriving Jackson of much needed manpower.[49] While Jackson repositioned his small brigade, Averell moved further south and went into camp. His advance camped about 15 miles (24 km) north of Huntersville.[49] Averell and Jackson were now aware of each other's proximity, and Jackson needed reinforcements for his small brigade.[50] Jackson's brigade consisted of the 19th and 20th Virginia Cavalry Regiments, a cavalry battalion consisting of four companies commanded by Major Joseph R. Kessler, and a battery that consisted of two 12-pounder howitzers. Only 750 men were available to Jackson three days later at Droop Mountain.[51]

Averell's trap

Averell resumed his march southward at 7:00 am on November 4, and burned two enemy campsites. Arriving at Huntersville and finding no enemy troops, he determined that a portion of the 19th Virginia Cavalry was six miles (9.7 km) west at Marling Bottom—and devised a plan to cut them off from their headquarters at Mill Point. About noon, he sent Schoonmaker and the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, with the 3rd West Virginia Mounted Infantry, southwest on Beaver Creek Road. Their objective was to reach the intersection with the Marling Bottom Road before the 19th Virginia Cavalry got there from Marling Bottom, and prevent the Virginians from reaching Mill Point and Hillsboro.[52] Averell was somewhat correct—Colonel Arnett and the 20th Virginia Cavalry Regiment (not the 19th) were at Marling Bottom, which is eight miles (13 km) north of Mill Point.[46]

Four hours later, Colonel Oley and the 8th West Virginia Mounted Infantry, which had been in the rear of Averell's command, arrived in Huntersville. Hoping to trap a portion of the Confederate cavalry between Schoonmaker and Oley, Averell immediately sent Oley west to Marling Bottom with a force that consisted of the 8th West Virginia, the 2nd West Virginia Mounted Infantry, and a section of Ewing's Artillery.[53] Hours earlier, Arnett and his brigade commander Jackson learned of the Union force on Beaver Creek Road. Arnett departed from Marling Bottom for Mill Point to unite with Jackson, setting blockades on the road as he went. Jackson sent a portion of the 19th Virginia Cavalry, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William P. Thompson, one mile (1.6 km) north on the Beaver Creek Road to blockade the road long enough for Arnett to pass through to Mill Point.[53] Thompson and Schoonmaker began skirmishing around 3:00 pm. Around dusk, Oley entered Marling Bottom, but Arnett was already gone and passed through the intersection near Mill Point after dark while Thompson continued skirmishing—Averell's trap had failed.[54]

Elsewhere, during the afternoon of November 4, two regiments from the Confederate cavalry brigade of Albert G. Jenkins were resting in Greenbrier County while their commander, Colonel Ferguson, consulted with Brigadier General Echols. Ferguson divided his brigade to assist Jackson at Mill Point and to protect Lewisburg. His 16th Virginia Cavalry Regiment was sent five miles (8.0 km) west of Lewisburg to guard one of the approaches to town. A portion of his 14th Virginia Cavalry Regiment guarded a second approach. The remaining six companies from the 14th Virginia Cavalry, commanded by Colonel James A. Cochran, rode north to assist Jackson at Mill Point.[54]

That evening at Mill Point, Jackson's Confederates assumed defensive positions on the southwest side of Stamping Creek, with Arnett commanding the "infantry" (dismounted cavalry).[55] Schoonmaker fought through Thompson's blockade and took a position on the northeast side of the creek. The two camps were separated by 300 yards (270 m) and a creek, and both sides could see each other. Oley was still in Marling Bottom, and Averell remained in Huntersville with the infantry and one battery.[36] Further east in the Shenandoah Valley, Brigadier General John Imboden was notified that Averell was in Greenbrier County with a large force.[56]

Fight at Mill Point

Early in the morning on November 5, Averell moved his infantry from Huntersville toward Mill Point, and Oley left Marlinton for the same destination.[57] Schoonmaker believed he was outnumbered three-to-one, and placed his force in a defensive position.[58] He began skirmishing with Jackson's two regiments around daylight. Jackson also made use of his two howitzers, which made the situation difficult for Schoonmaker because he had no artillery. Oley, who was about nine miles (14 km) away, could hear the artillery—and knew that Schoonmaker had none.[57] He hurried his two mounted regiments and battery toward the front. Upon arrival, he found Schoonmaker facing strong pressure. Schoonmaker had him dismount his two regiments and deploy them on the right (west) while Schoonmaker and his two regiments took the left (east) side. Ewing's battery, which had longer range than Jackson's howitzers, was placed in between.[59][60]

Jackson was aware of the Union reinforcement, and also knew that his howitzers did not have the range of the Union guns. He chose to fall back to Droop Mountain, which was just south of Hillsboro and about 24 miles (39 km) north of Lewisburg.[60] Arnett led his men to the top of the mountain adjacent to the road, using a route that had forest and hills for cover.[55] Lieutenant Colonel Thompson and 32 men from the cavalry covered the rear and defended against a Union cavalry assault.[61] When Lurty's Battery, already positioned on the mountain, began shelling the pursuing Union cavalry, all fighting ended.[62] Averell and his infantry arrived at Mill Point around the time Jackson was falling back to Droop Mountain.[60] The Union soldiers went into camp around 2:00 pm after fighting stopped. Averell, who's November 7 report said he "attacked Jenkins in front of Mill Point" (actually Jackson), said there was a "trifling loss on either side".[63]

Confederates prepare

When Jackson and Arnett reached the summit of Droop Mountain on November 5, they deployed Arnett's 20th Virginia Cavalry in a defensive position at a high point next to the road. The crest of Droop Mountain is 3,100 feet (940 m) high, and Jackson could see Union Army camps around Hillsboro.[64] Jackson had about 750 men, since a squadron (Siple's) was cut off further north in Pocahontas County.[65]

About 100 miles (160 km) away, Imboden's Brigade had moved to Buffalo Gap in Virginia's Augusta County, but did not depart from there until November 6. He had about 600 mounted men and a section of artillery.[66] At Lewisburg, Echols decided to bring more reinforcements to Jackson despite his worry that another Union force might attack from the west and cause the entire Confederate force to be surrounded. (Duffié was, in fact, approaching from the west.)[67] Echols covered half the distance to Droop Mountain on November 5, and camped at Spring Creek near the Greenbrier River.[68] That evening, Cochran and six companies from the 14th Virginia Cavalry arrived at Droop Mountain as the first group of reinforcements for Jackson.[69] At 2:00 am on November 6, Echols resumed his march to Droop Mountain.[70] After about two miles (3.2 km), he realized that the road from Falling Springs to Hillsboro could be used by Union soldiers to attack Jackson's extreme right flank. Wary of a Union trap, he detached the 26th (Edgar's) Infantry Battalion, with one piece of artillery, to block the road.[71]

Battle

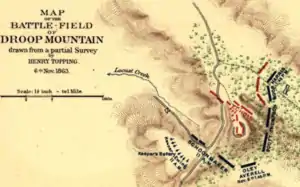

Averell's plan

Averell was up early in the morning on November 6 planning his strategy, and began moving his troops from Mill Point to Hillsboro shortly after sunrise. Skirmishers went further south on diverse maneuvers for the purpose of confusing the Confederates.[72] As the Confederate skirmishers fell back to the mountain, Averell inspected the terrain and enemy positions. He determined that a frontal assault would be a disaster, and made a plan for a three-sided dismounted attack. While a portion of his troops on his left would divert the attention of the Confederates, a large portion would flank the enemy from the right. In the final phase, more troops would attack from the front and right.[73] Beginning the flanking maneuver, Colonel Augustus Moor departed shortly after 9:00 am with 1,175 men. His force included the 10th West Virginia Infantry, the 28th Ohio Infantry, Company C of the 16th Illinois Cavalry Regiment, and a small group of signalman from the 68th New York Infantry led by Lieutenant Abraham C. Merritt. Colonel Thomas M. Harris led the 10th West Virginia Infantry, and Lieutenant Colonel Gottfried Becker led Moor's 28th Ohio Infantry when needed. Moor's force fell back about one mile (1.6 km), then began an obscure circuitous route of six miles (9.7 km) to nine miles (14 km) that would put them on the enemy's left flank.[73] Schoonmaker and the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry moved to the left (Confederate right) with the artillery, where they made sure they had the attention of Jackson's men at the top of the mountain.[74] The Union battery was positioned on a hill that was 500 feet (150 m) lower than the Confederate guns, making it difficult to achieve the same accuracy as the Confederate cannons.[75]

Echols takes over

Brigadier General Echols arrived at Droop Mountain with reinforcements around 9:00 am on November 6, bringing Colonel Ferguson from Jenkins' Brigade with him.[76][77] Echols brought the 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment, the 23rd Virginia Infantry Battalion (a.k.a. Derrick's Battalion), Chapman's Battery, and Jackson's Battery from Jenkins' Brigade.[77] Their arrival was acknowledged by loud rebel yells and music from a band—making sure both sides knew about the reinforcement.[78] Echols assumed command of all forces, and Colonel George S. Patton commanded Echols' Brigade. Major Robert A. "Gus" Bailey commanded the brigade's 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment, and the 23rd Virginia Infantry Battalion was commanded by Major William Blessing.[79] Major William L. McLaughlin commanded the two batteries.[67] Echols placed his two batteries on his right close to Colonel Jackson's two howitzers. Blessing's Battalion (a.k.a. Derrick's Battalion) was placed on the Confederate right on the right side of the road to Lewisburg. Bailey and the 22nd Virginia were placed behind the artillery.[80][81] The total Confederate force engaged in the battle, mostly dismounted cavalry, numbered 1,700.[82] Throughout most of the battle, Echols would command the Confederate right, Jackson the center, and the left was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William P. Thompson (not to be confused with Lieutenant Colonel Francis W. Thompson, commander of the 3rd West Virginia Mounted Infantry).[80]

Battle begins

Although some skirmishing already happened, historians consider artillery shots fired at Droop Mountain by Schoonmaker using Keeper's Battery, which occurred around 11:00 am, as the beginning of the battle.[83][Note 5] Artillery fire continued all day, but the Union cannons were not able to hit enemy artillery. Confederate artillery was accurate and eventually killed almost all the horses belonging to Ewing's Battery (Battery G).[85] Keeper's Battery (Battery B) had two people killed and five wounded.[63] By noon, Schoonmaker realized he could not hit enemy artillery, so he withdrew two of the three sections of Keepers Battery to preserve the guns and ammunition.[86]

Between noon and 1:00 pm, Averell readied his men for the center and right-center dismounted assault. In the case of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Scott's 2nd West Virginia Mounted Infantry, the men dismounted near the front and remained out of sight while waiting for orders. Scott's men were positioned on the right center, between Oley's 8th West Virginia Mounted Infantry on the left and Colonel Francis S. Thompson's 3rd West Virginia Mounted Infantry on the right.[87] Around 1:00 pm, Schoonmaker repositioned two sections of artillery while preparing to assist in the frontal attack on his right. At that time, Lieutenant Joseph W. Daniels of Keepers Battery was decapitated by artillery fire while standing next to Schoonmaker.[88] The main body of Schoonmaker's troops did not get to the foot of the mountain in time to assist the three regiments making the frontal assault, although his advance did.[75]

Moor finds the Confederate left

On the far right (or Confederate left) Colonel Moor encountered the Confederate left flank at about 1:45 .[89] The 28th Ohio Infantry and Lieutenant Colonel Becker led the way and met Captain Jacob W. Marshall of the 19th Virginia Cavalry, who was reinforced by a group of 50 dismounted cavalry men led by Major Joseph R. Kessler. The Confederate force, numbering about 200, surprised Becker with a charge from close by that drove the 28th Ohio Infantry back. Understanding he was outnumbered, William Thompson sent a request to Echols for more reinforcements. Echols responded by sending 300 men from the 23rd Virginia Infantry Battalion and two companies from the 14th Virginia Cavalry—Company B and Company I. Those two companies were equipped for close-quarters fighting, as they were armed with sabers, pistols, and carbines.[90] Moor responded to the initial Confederate thrust by ordering his Ohio infantrymen to lie down and "fire by file".[91] Colonel Thomas M. Harris and the 10th West Virginia Infantry moved to the front on Moor's right and began pushing their outnumbered enemy back.[92]

Center attack

Although signals from Moor on the Confederate left were not received, the sounds from the fighting and the Confederate "disturbed appearance in front" led Averell to conclude that it was time for the attack at the center.[93][94] Averell's three mounted infantry regiments began advancing up the mountain while dismounted, with Francis Thompson's 3rd West Virginia Infantry making the most progress and the 8th West Virginia Infantry struggling with the steep and barren mountainside.[87] They faced sharpshooters, musket fire from breastworks, and battery fire of grape and canister.[95] Schoonmaker briefly advanced two guns from Ewing's Battery partially up the mountainside, where they fired upon the 22nd Virginia Infantry. Return fire from Chapman and Lurty caused the Union guns to back off.[96] The 3rd West Virginia Infantry found Moor's left, and Echols began to face five Union regiments on his left and center. The Confederate center was strongly defended by portions of the 14th Virginia Cavalry commanded by Colonel Cochran and the 20th Virginia Cavalry commanded by Colonel Arnett. When the Union regiments reached the breastworks, the fighting was hand-to-hand at the top as Confederate soldiers used their empty muskets as clubs. After Union soldiers began sticking only their pistols over the breastworks and firing blindly, the Confederates eventually retreated.[97] The 2nd West Virginia Infantry, which had the most casualties of the three center-attack regiments, was the first to enter the Confederate breastworks.[98] Both Jackson and McLaughlin recognized that the Confederate center defense was faltering, and moved most of the artillery to the rear where it could be used to cover a retreat if necessary.[99]

Resistance crumbles

Although the 23rd Virginia Infantry Battalion helped William Thompson's men stall Moor's large infantry force, the Confederates on the extreme left were being driven back toward the center, forming a dangerous angle in their line. After receiving a report from Thompson, Echols shifted Patton and three companies to the left and joined Jackson at the center. The reinforcements temporarily checked the Union advance, but sustained a high number of casualties and was not strong enough to stop Moor's advance. The Confederate center and right were also in trouble, as Ewing's Battery found a target and some of Jackson's men began fleeing toward the rear.[99] A signalman from the 68th New York Infantry signal corps detachment observed the Confederate disarray, and Averell received the news near 3:00 pm. Averell ordered Major Thomas Gibson, who's Independent Cavalry Battalion was held in reserve almost four miles (6.4 km) back, to advance as quickly as possible. A section of Ewing's Battery was also sent in pursuit. The battle was mostly finished by 4:00 pm, and Echols received news about then that Duffié was at a mountaintop only 18 miles (29 km) west of Lewisburg.[100][Note 6] With both his left and right flanks breached, Echols ordered Jackson and Patton to fall back. Major Blessing and the 23rd Infantry Battalion (Derrick's Battalion) were ordered to fall back to the road to Lewisburg. Moor's infantry advanced from the Confederate left to the Confederate right where the Confederate artillery had been posted on a hill. Although the Confederates were able to withdraw their last two pieces of artillery that were still on the hill, Moor's presence caused some Confederate panic as men feared being cut off and captured.[100]

Retreat and pursuit

One of the last Confederate officers to leave Droop Mountain was Major Robert Augustus Bailey, of the 22nd Virginia Infantry. Bailey was mortally wounded trying to rally his men. His regiment started the battle with 550 men, and had 113 casualties. The regiment also had three captains wounded (two seriously), and one lieutenant mortally wounded. By the time Bailey was shot, the pike to Lewisburg was "blocked with artillery, caissons, wagons, and horses."[101] The Confederate retreat became even more urgent, and weapons were being thrown away as the men ran. At least one officer is known to have ordered his company to "get out and save yourselves".[102] Many of the Confederate soldiers ran to the woods. Colonel Patton was unable to reorganize his command until he arrived at Frankford—19 miles (31 km) south of the battle.[101] Both Colonel Cochran and Lieutenant Colonel Thompson were thought to be captured or killed, but were unharmed and eventually returned to their units.[103] The 26th Virginia Infantry Battalion, which had been posted on another road before the battle, became cut off from Echols' Battalion.[104]

The first pursuers of the Confederate Army were Moor's infantry, who fired into the retreating rebels from the original location of the Confederate artillery. Moor described a scene of dead and wounded horses, a "fast-moving mass" that "melted away by scattering through the woods south of the pike."[91] Moor's infantry pursued the Confederates about six miles (9.7 km), before stopping after dark to go into camp.[91] Other pursuers were Gibson's Independent Cavalry Battalion and Ewing's Battery, who advanced about seven miles (11 km) before falling back one mile (1.6 km) in the dark.[105] Schoonmaker reported going into camp at 8:00 pm.[105]

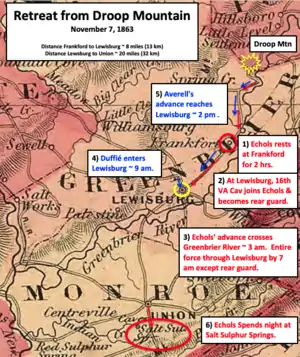

Lewisburg

Duffié skirmished with enemy pickets on Little Sewell Mountain on November 6, and continued on to Meadow Bluff—about 15 miles (24 km) from Lewisburg. His advance guard was briefly attacked at 2:00 am on November 7, and his command was moving toward Lewisburg by 3:00 am. The command arrived in Lewisburg at 9:00 am, as the Confederate read guard was departing. Most of the Confederate Army passed through 2 hours earlier.[44] The Confederate read guard was the 16th Virginia Cavalry Regiment, which had been guarding the western approach to Lewisburg and had not endured fighting at Droop Mountain.[106] Duffié began a pursuit with the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry as the advance, but returned to Lewisburg after finding blockades and a burnt bridge at the Greenbrier River.[44] The 2nd West Virginia Cavalry captured 110 head of cattle and a small number of the enemy. At Lewisburg the knapsacks and tents of the 22nd Virginia Infantry were captured in addition to supplies.[107] Averell had Schoonmaker's cavalry in the advance on the morning of November 7. Upon arriving in Lewisburg, Schoonmaker found looting that was ended by his provost marshal.[75] Duffié reported that Averell arrived in Lewisburg around 4:30 pm.[44] By the evening, Echols was in Monroe County close to the Virginia border at Salt Sulphur.[108]

Expedition ends

The pursuit of Echols ended on August 8, and Averell and Duffié appeared to blame each other for the stoppage. Averell reported that he began the pursuit on the morning of November 8, but ended the search because of a "formidable blockade", being "encumbered" with prisoners and captured property, and Duffié’s infantry being "unfit for further operations".[109] Duffié’s report said he made the pursuit on the morning of November 8 with his cavalry and mounted infantry, and he "received an order from General Averell to return" when he was eight miles (13 km) from Union, West Virginia.[110] One important factor in the decision to end the chase was that Averell was informed that reinforcements would be waiting for Echols at the Dublin Rail Depot.[111] Although he could not have known, only the 36th Virginia Infantry Regiment with a battery was moving toward Echols' destination of Salt Pond Mountain.[108] The 26th Virginia Infantry Battalion, which did not engage at Droop Mountain and became cut off from the main force, was able to reunite with Echols in Virginia by November 10—and had several hundred additional men that fled the battle.[112]

Duffié began a move to Meadow Bluff as ordered, but found that location impractical because of bad weather and difficulties with the supply line.[113] He endured a snowstorm on Sewell Mountain and returned to Charleston on November 13.[107] Moor, with the 28th Ohio Infantry, 10th West Virginia Infantry, and Keeper's Battery, was sent back to Beverly. Moor took the prisoners and wounded, and reached his destination on November 12. Averell moved north with the cavalry, mounted infantry, and Ewing's Battery.[109] They moved through White Sulphur Springs, where Averell learned that enemy troops were nearby.[114]

Imboden reached Covington in Virginia's Alleghany County on November 8. There he found 100 to 200 men from Jackson's command that had fled Droop Mountain. During the night, more men arrived. He also had 800 more men, and two 6-pounder guns from the Rockbridge Home Guard and Cadets about 13 miles (21 km) away at Clifton Forge.[115]

Averell detached two squadrons of the 8th West Virginia Mounted Infantry, under the command of Major Hedgmen Slack, on the evening of November 8. On the next day, Slack had a small confrontation with Imboden's rear guard near Covington, capturing 21 men. However, Slack believed that Imboden was moving his command south toward the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad to reinforce Echols, and neither side pursued each other.[114] Averell reached New Creek on November 17, bringing prisoners and captured horses.[109]

Casualties

Averell had 45 men killed, including those mortally wounded. He also had 93 wounded and 2 captured.[116][Note 7] This total of 140 casualties agrees with the National Park Service summary.[118] The original report listed 30 killed as part of 119 casualties, although some of the mortally wounded may not have died at the time of the report. The 10th West Virginia Infantry, followed by the 28th Ohio Infantry, had the most casualties.[63] For Confederate troops, 33 were killed, 121 wounded, and 122 captured. The 19th Virginia Cavalry and the 22nd Virginia Infantry had the most casualties.[117] The total of 276 casualties almost matches the count of 275 reported by Echols and used by the National Park Service.[82][118]

Aftermath

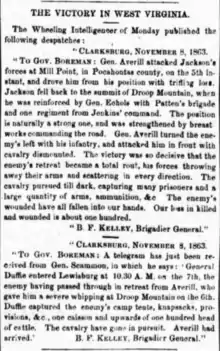

Averell reported that his Droop Mountain "victory was decisive and the enemy's retreat became a total rout".[63] However, Duffié reported that "Had General Averell, instead of attacking the enemy in force and making a general engagement, engaged him lightly, detaining him until my command reached Lewisburg, it is my opinion that we might have captured almost the entire rebel force."[113] The Confederates were aware that if they had held their line on the mountain, they would have become trapped between Duffié and Averell. They also knew that if they had not retreated (or ran) when they did, they would have been surrounded by Averell's two wings of infantry led by Moor and Oley.[119] One historian was critical of Averell's decision to end the mission, writing that if Averell had "the drive and the instinct for the jugular" of someone like Philip Sheridan or George Armstrong Custer, he would have continued pursuing Echols and gone on to the railroad bridge.[111]

On November 7, Major General Sam Jones sent a report to General Samuel Cooper in Richmond requesting assistance and saying that Echols was badly defeated, closely pursued, and would probably not escape.[120] By November 15, Jones believed the affair at Droop Mountain was not as big of a loss as he originally thought. On December 11, he reported that Confederate troops had reoccupied their positions held prior to the battle, and the enemy had suffered heavier losses than those inflicted.[121]

After the Battle of Droop Mountain, the only major battles in West Virginia were the Battle of Moorefield, the Battle of Summit Point, and the Battle of Smithfield Crossing. All three battles were in the Eastern Panhandle of the state.[6] Some historians conclude that Confederate resistance in West Virginia collapsed after the Battle of Droop Mountain.[118] However, the Confederates returned to their original positions in December, and fighting may have simply shifted to the Shenandoah Valley.[122] At worst (for the Union cause), the Battle of Droop Mountain can be considered a tactical victory for Echols, since the Confederate Army was not eliminated from West Virginia and the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was unharmed. In December, Halleck again ordered Averell to destroy the railroad and another expedition started.[18] At best, the Battle of Droop Mountain was a sound victory for Averell and a morale booster. President Abraham Lincoln made reference to the battle it in a speech, and Major General Ambrose Burnside confirmed that the victory encouraged his Army of the Ohio in Tennessee.[123]

Future leaders

Averell was often criticized for being too cautious, and was removed in September 1864 as a division commander by General Philip Sheridan for not pursuing the enemy promptly enough.[124] However, Averell was one of the few Union cavalry leaders that achieved cavalry victories in the eastern theater before Sheridan arrived. In addition to Droop Mountain, he soundly defeated the Confederates at the Battle of Rutherford's Farm and the Battle of Moorefield. He also performed well at the Battle of Kelly's Ford. Historian Scott Patchan noted that Averell had successes while "serving as an independent or quasi-independent commander, while his failures arose when his superiors expected him to cooperate within the framework of a larger command structure."[125]

Averell and Echols were the generals on the field at the Battle of Droop Mountain. Of the Union leaders in the battle, Harris, Moor, and Oley eventually became generals.[126] Schoonmaker led a charge against a fort in the Third Battle of Winchester, and was awarded the Medal of Honor.[127][128] Harris served on the commission that tried the Lincoln assassination conspirators.[129] For the Confederates, Jackson eventually became a general, while Patton would have become a general if he had survived his wounds received at the Third Battle of Winchester.[126] Patton is the grandfather of the famous World War II tank commander, George S. Patton.[130]

Notes

Footnotes

- A soldier from the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry Regiment called Lewisburg a "hot rebel town", and described its inhabitants cheering Confederate soldiers in a May 1862 battle.[5]

- Some sources, and Jones himself, called Jones' command the Department of Western Virginia and East Tennessee.[24][23] Other sources call his command the Department of Western Virginia.[25][26]

- Estimates of the number of men in Averell's brigade range from 3,000 to 7,000.[39] Lowry says Averell reported 3,855 officers and men on August 31, 1863, and did not engage in any significant fighting between then and the Battle of Droop Mountain. He concludes that Averell's force at Droop Mountain was that total less men absent for furloughs, illness, or detached service.[39]

- Marlinton, the county seat of Pocahontas County, was originally named Marlin's Bottom. It was renamed Marlinton in 1887.[47] It was also described as Marling's Bottom in the 1860s, and shown as Marling Bottom on some maps.[30][48]

- Echols believed his artillery started the battle, writing that his artillery "after being placed in position opened upon the enemy in the valley beneath, the enemy's artillery for some time replying vigorously...."[77] His artillery commander, Major William McLaughlin, disagreed—reporting that the enemy "opened fire" and he "promptly replied".[84]

- Confederate Brigadier General Echols uses 4:00 pm as "when the battle ceased" in his report.[82]

- The casualties used herein, for Union and Confederate troops, are based on a detailed study by historian Terry Lowry.[116][117]

Citations

- Snell 2011, Ch. 1 of e-book

- "West Virginia History - Statehood for West Virginia: An Illegal Act?". West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- "Civil Neighbors to Violent Foes: Guerrilla Warfare in Western Virginia during the Civil War". Marshall University. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- Snell 2011, Ch. 2 of e-book

- Sutton 2001, p. 53

- "West Virginia Civil War Battles". National Park Service. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- "Lewisburg National Register Historic District/Greenbrier County Visitor Center". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- Starr 1981, pp. 154-156

- Snell 2011, Ch. 4 of e-book

- Lowry 1996, p. 6

- Nolting, Mike (2020-05-24). "Former State Park Superintendent Reflects on Battle of Droop Mountain". MetroNews - The Voice of West Virginia. West Virginia MetroNews Network. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- Bogart & Ambrose 2014, p. 28

- Whisonant 2015, p. 157

- "Geology and the Civil War in Southwest Virginia: The Wythe County Mines" (PDF). Commonwealth of Virginia, Division of Mineral Resources (May 1996). Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- "Virginia Center for Civil War Studies - Wytheville". Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech). Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- Scott 1890, p. 43

- Scott 1890, pp. 499-502

- Starr 1981, p. 165

- William Willis Blackford (1856). Map & Profile of the Virginia & Tennessee Rail Road (Map). Richmond, Virginia: Ritchie & Dunnavant (Library of Congress). Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- Starr 1981, p. 161

- "Map of Allegany with Folck's Mill". Western Maryland Regional Library. Retrieved 2020-10-01.

- "The Civil War in West Virginia". West Virginia Archives and History. West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- Scott 1890, p. 525

- Lowry 1996, p. 5

- Hewitt & Bergeron 2010, p. 13

- Knight 2010, p. 15

- Lowry 1996, p. 114

- Scott 1890, p. 528

- "Rantings of a Civil War Historian - Brig. Gen. William L. "Mudwall" Jackson". Rantings of a Civil War Historian - Bringing Obscurity into Focus. Eric J. Wittenberg. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- Scott 1890, p. 536

- Scott 1890, p. 547

- Lowry 1996, p. 52

- Steelhammer, Rick (2013-05-19). "I-64 Gas Stop Sparks Book on Obscure W.Va. Civil War Battle". Charleston Gazette-Mail. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- Lowry 1996, p. 11

- Lowry 1996, p. 64

- Lowry 1996, p. 74

- Lowry 1996, p. 26

- Lowry 1996, p. 21

- Lowry 1996, p. 32

- Scott 1890, p. 522

- Sutton 2001, p. 109

- United States Congress 1891, p. 1003

- "Yankee Raid Upon Wytheville". Staunton Spectator. 1863-07-28. p. 2.

The result of this fight was, that the Yankees lost a Colonel, (Toland) Major, and had another Colonel (Powell) severely wounded ...

- Scott 1890, p. 523

- Lowry 1996, pp. 63-64

- Lowry 1996, p. 65

- Wilcox, Rivard Dwain (2016-06-30). "Marlinton – The Way We Were". Pocahontas Times. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- G.W. & C.B. Colton & Co. (Library of Congress) (1876). Colton's New Topographical Map of the States of Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland & Delaware: and Portions of Other Adjoining States (Map). New York, New York (Washington, District of Columbia): G.W. & C.B. Colton & Co. (Library of Congress). Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- Lowry 1996, p. 66

- Lowry 1996, p. 67

- Lowry 1996, pp. 49-52

- Lowry 1996, p. 68

- Lowry 1996, p. 70

- Lowry 1996, p. 72

- Scott 1890, p. 544

- Lowry 1996, p. 75

- Lowry 1996, p. 77

- Scott 1890, p. 518

- Scott 1890, p. 515

- Lowry 1996, p. 82

- Lowry 1996, p. 84

- Lowry 1996, p. 86

- Scott 1890, p. 503

- Lowry 1996, p. 88

- Lowry 1996, p. 93

- Scott 1890, p. 548

- Lowry 1996, p. 83

- Lowry 1996, p. 90

- Scott 1890, p. 537

- Scott 1890, p. 529

- Lowry 1996, p. 97

- Lowry 1996, p. 101

- Lowry 1996, pp. 102-104

- Lowry 1996, p. 104

- Scott 1890, p. 519

- Scott 1890, p. 545

- Scott 1890, p. 538

- Lowry 1996, p. 105

- Lowry 1996, p. 43

- Lowry 1996, p. 106

- Lowry 1996, p. 107

- Scott 1890, p. 531

- Lowry 1996, pp. 113-114

- Scott 1890, p. 546

- Lowry 1996, p. 115

- Scott 1890, pp. 518-519

- Lowry 1996, p. 118

- Lowry 1996, pp. 119-120

- Lowry 1996, p. 125

- Lowry 1996, pp. 129-131

- Scott 1890, p. 511

- Lowry 1996, p. 136

- Scott 1890, p. 509

- Scott 1890, p. 506

- Lowry 1996, p. 122

- Lowry 1996, p. 133

- Lowry 1996, p. 143

- Lowry 1996, p. 150

- Lowry 1996, p. 152-155

- Lowry 1996, pp. 159-161

- Scott 1890, pp. 533-534

- Lowry 1996, p. 167

- Lowry 1996, p. 183

- Scott 1890, p. 532

- Scott 1890, p. 521

- Lowry 1996, p. 192

- Sutton 2001, pp. 109-110

- Lowry 1996, p. 195

- Scott 1890, p. 507

- Scott 1890, pp. 523-524

- Starr 1981, p. 164

- Lowry 1996, p. 206

- Scott 1890, p. 524

- Scott 1890, p. 517

- Lowry 1996, pp. 200-201

- Lowry 1996, p. 259

- Lowry 1996, p. 269

- "Battle Detail - Droop Mountain". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- "Battle of Droop Mountain - Letter, James McChesney to Mother - McChesney Papers". West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- Scott 1890, pp. 525-526

- Scott 1890, pp. 527-528

- Lowry 1996, p. 222

- Lowry 1996, p. 221

- Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 505

- Patchan 2007, p. 119

- Lowry 1996, p. 237

- Lowry 1996, p. 226

- "James M. Schoonmaker U.S. Civil War". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- Lowry 1996, p. 228

- "Patton Family at VMI". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

References

- Ainsworth, Fred C.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1902). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies - Series I Volume XLII Part I - Additions and Corrections, Chapter LV. Washington, District of Columbia: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 427057. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- Bogart, Charles H.; Ambrose, William M. (2014). First Kentucky Independent Battery (Simmonds' Battery): The only Kentucky Unit to Fight in the Eastern theater for the Federal Army. Frankfort, Kentucky: Yellow Sparks Press. ISBN 978-1-31244-231-3. OCLC 908834960.

- Hewitt, Lawrence L.; Bergeron, Arthur W. (2010). Confederate Generals in the Western Theater. Volume 2, Essays on America's Civil War. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-699-5. OCLC 1126026346.

- Knight, Charles R. (2010). Valley Thunder: The Battle of New Market and the Opening of the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, May 1864. New York, New York: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-054-5. OCLC 763157018.

- Lowry, Terry (1996). Last Sleep: The Battle of Droop Mountain, November 6, 1863. Charleston, West Virginia: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-57510-024-1. OCLC 36488613.

- Patchan, Scott C. (2007). Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0700-4. OCLC 122563754.

- Scott, Robert N. (1890). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies - Series I Volume XXIX Part I - Reports, Chapter XLI. Washington, District of Columbia: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1-57510-024-1. OCLC 36488613. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- Snell, Mark A. (2011). West Virginia and the Civil War : Mountaineers are Always Free. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 978-1-61423-390-9. OCLC 829025932.

- Starr, Stephen Z. (1981). Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 4492585.

- Sutton, Joseph J. (2001) [1892]. History of the Second Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry Volunteers, During the War of the Rebellion. Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press. ISBN 978-0-9628866-5-2. OCLC 263148491.

- United States Congress (1891). "The Miscellaneous Documents of the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Fifty-First Congress 1889-'90". The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXVII Part II. U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 191710879. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- Whisonant, Robert C. (2015). Arming the Confederacy : How Virginia's Minerals Forged the Rebel War Machine. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-14508-2. OCLC 903929889.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Droop Mountain. |