Wytheville Raid

The Wytheville Raid or Toland's Raid (July 18, 1863) was an attack by an undersized Union brigade on a Confederate town during the American Civil War. Union Colonel John Toland led a brigade of over 800 men against a Confederate force of about 130 soldiers and 120 civilians. The location of Wytheville, the county seat of Wythe County in southwestern Virginia, had strategic importance because of a nearby lead mine and the railroad that served it. This mine supplied lead for about one third of the Confederate Army's munitions, while the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad transported Confederate troops and supplies; plus telegraph wires along the railroad line were vital for communications. In addition to logistics of moving the lead to bullet manufacturing facilities, this rail line also connected an important salt works of an adjacent county with the wider Confederacy.

| Wytheville Raid | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Wythe County in Virginia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Col. John Toland † Col. William H. Powell |

Maj. Thomas M. Bowyer Maj. Joseph Kent | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

34th Ohio Infantry 2nd WV Cavalry (6 co.) 1st WV Cavalry (2 co.) |

Virginia Infantry Wytheville Home Guard Civilians | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 818 | 250 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 11 killed, 32 wounded, 17 prisoners, 26 missing |

USA Report: 75 killed, unknown wounded, 125 prisoners (paroled) CSA Report: 3 soldiers killed | ||||||

| Union troops captured town but retreated hours later. Union losses included two colonels and a captain. | |||||||

Toland's entire brigade was mounted, and consisted of a mounted infantry regiment plus eight companies of cavalry. It approached the small town of Wytheville on the evening of July 18. The community had been warned that a large force of Union horsemen was heading in its direction, and hastily made preparations before the brigade's arrival. While many in the community fled south or hid in their homes, a force of about 120 civilians (including home guard) volunteered to defend their town. The Union cavalry entered the town first, charging in column down the main road that led into town. The men from the cavalry were ambushed by Confederate soldiers, Home Guard, and local citizens. Most of the local men, and women, fired their one–shot muskets from inside their homes and businesses. This type of warfare was considered unconventional at the time. One Union soldier described the road as an "avenue of death".[1]

The Union force suffered significant losses. The Union commander, Colonel Toland, was killed. The severely wounded cavalry commander, Colonel William H. Powell, was left to die and became a prisoner of the Confederates. (Powell was also second in command of the entire brigade.) Additional officers and enlisted men were killed, wounded, or missing. The Union after action report listed a total of 86 men killed, wounded, missing, or taken prisoner during the entire expedition—although Confederate leadership believed the Union casualties were much higher. (The entire expedition includes the trips to and from Wytheville.) Approximately 300 horses were lost (killed, wounded, or injured) by the brigade during the raid and retreat—including an estimated 80 killed on the streets of Wytheville. Despite significant losses, the Union brigade was eventually able to secure the town. However, the victory was costly, and the northerners retreated less than 24 hours after entering the small community. A group of soldiers and civilians, less than one third the size of the Union force they opposed, prevented a brigade from destroying vital assets of the Confederacy—a railroad line, telegraph line along the railroad, a lead mine, and possibly a salt mine. After the conflict, Union infantry leaders were critical of the Union cavalry's performance, and men from the cavalry were critical of the infantry leadership's tactics.

Wythe County

Wythe County is located in southwestern Virginia near the Blue Ridge Mountains. It was created in 1790, and named after George Wythe.[2] Wythe was a legal mentor to Thomas Jefferson during the 1760s, and signed the Declaration of Independence.[3] The crossroads town of Wytheville was the county seat during the Civil War, and remains so today. According to the 1860 census, the county's population was 12,305, and Wytheville's population was 1,111.[4][5] Wytheville was said to have 1,800 "inhabitants" in 1863.[6]

Wythe County had two resources that caught the attention of the Union army during the Civil War—a lead mine and a railroad. The lead mine was located about 10 miles (16.1 km) southeast of Wytheville in the unincorporated community of Austinville.[7] The mine was the source for a significant portion, estimated to be about one third, of the lead used by the Confederacy to produce bullets for its armies.[8]

The Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, which ran roughly east–west through the county, served the lead mine. Telegraph lines strung along the railroad were vital for communications in the region, and enabled communications between the Confederate capitol of Richmond and points as far west as Tennessee.[9] In addition, the railroad was important for transporting Confederate troops and supplies.[10] The railroad had a station located about 0.75 mi (1.2 km) south of the center of Wytheville. Ammunition and weapons for the Confederate Army were often stored there.[11] Thus, the town had a strategic significance during the American Civil War, and was often a target.[Note 1]

Because of the railroad, Wytheville was connected to two more points of military significance. A small headquarters for the Confederate army was located about 44 mi (70.8 km) west of Wytheville at the western edge the adjacent Smyth County.[13] The army outpost was at the community named Saltville, which was the home of a salt mine that was important to the Confederacy. Salt is essential for the diet of humans and livestock, and was also used (at the time) to preserve meat. Salt was not widely available during the Civil War, and eight states used salt from this mine.[Note 2] More fighting would occur at Saltville in 1864. About 25 mi (40.2 km) east of Wytheville in Pulaski County is the Dublin railroad depot, which was a regional headquarters for the Confederate Army.[15] The Dublin Depot was originally named Newbern Depot, although the town of Newbern is 2 mi (3.2 km) south of the railroad line. A short time before the Civil War, the depot was renamed Dublin Depot in honor of the New Dublin Presbyterian Church, which was located nearby. Thus, some maps from the early 1860s still used New Bern to identify the depot.[16]

Union brigade

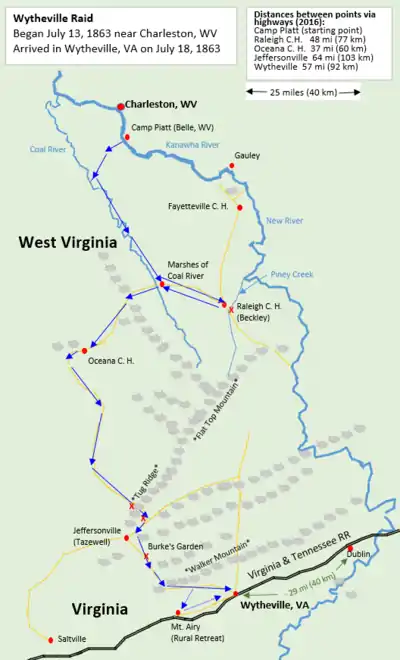

On the afternoon of July 13, 1863, a brigade of 870 Union soldiers departed their base camp located a few miles upriver (east) of Charleston, West Virginia. Their orders, which came from General Eliakim P. Scammon, were to disable the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad. Telegraph line strung along the railroad line was also a target. If circumstances allowed, nearby lead and salt mines would also be objectives.[17] Although the railroad, lead mine, and salt mine were obvious targets, communications sent by General Scammon were in code. Thus, exact details of the plan were known by few.[18]

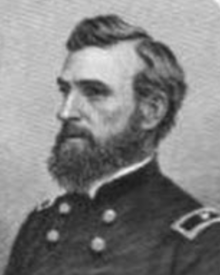

The Union brigade consisted of 365 men from the 2nd West Virginia Volunteer Cavalry Regiment and 505 men from the 34th Ohio Volunteer Infantry.[Note 3] This combined force is considered undersized for a Civil War brigade, which usually consisted of about 2,600 soldiers.[20] Colonel John T. Toland was the acting brigadier general, and therefore commanded the brigade. He was from the 34th Ohio Volunteer Infantry.[21] Toland had performed with "utmost bravery and valor" in the Kanawha Valley Campaign, which occurred during September 1862.[22] During the campaign, Toland twice escaped serious injury while his horses were killed.[23]

The infantry commander was Lieutenant Colonel Freeman E. Franklin.[21] The 34th Ohio Volunteer Infantry was also known as "Piatt's Zouaves" or the "1st Ohio Zouaves", and typically served as a mounted infantry, including in this expedition. As mounted infantry, Piatt's Zouaves used horses for transportation, but (unlike cavalry) fought dismounted. Their infantry weapons were heavier and had longer range than the light weapons used by cavalry.[24] Colonel Abram S. Piatt, who retired in 1862 after injuries, was their original commander. Piatt's Zouaves wore distinctive caps and uniforms trimmed in red, but did not always have the Asian-style baggy pants with open jackets typical of zouave units.[25] Regiments that dressed as zouaves during the Civil War were copying the look (and hopefully the discipline) of elite French troops that fought successfully during the 1850s in northern Africa.[26]

Colonel William H. Powell was commander of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry regiment, and second in command of the brigade. Powell also performed well in the Kanawha Valley Campaign, leading (as a major) the advance guard of the 2nd Loyal (West) Virginia Cavalry that successfully attacked a larger rebel cavalry and drove it away.[Note 4]</ref> If the rebel cavalry had not been removed from its position, the entire Union army in the Kanawha River Valley would have been surrounded and prevented from retreating to safety.[23] During November 1862, Powell led a group of 22 men that captured an entire rebel camp in what became known as the Sinking Creek Raid. For this action, Powell was later awarded the Medal of Honor.[27] Powell, who had been told by General George Crook to not return from the Sinking Creek Raid without good results, received a letter from Crook in 1889 that said "... I have always regarded the part you took in that expedition as one of the most daring, brilliant and successful of the whole war."[28]

Raleigh

After departing from camp, the brigade traveled along the Coal River, moving upriver about 50 mi (80.5 km) without significant incidents. Traveling along the river required numerous river crossings. On the evening of July 14, the advance guard (the cavalry's Company C) was about 4 mi (6.4 km) east of Raleigh Court House (also known as Beckley, West Virginia) when it was ambushed while crossing Piney Creek.[29][Note 5] A sergeant was killed, and a private mortally wounded. Three additional men were wounded.[31][Note 6] Colonel Toland sent forward two companies of infantry as skirmishers, which soon drove the Confederate force away.[33]

After the incident, the men were ordered to fall back to the pike that was located between the West Virginia communities of Raleigh Court House and Oceana. (At the time, Oceana was the county seat of Wyoming County.) The brigade became separated into two groups during this time (early morning before sunrise on July 15) because the portion led by Lieutenant Colonel Franklin had not received the order to fall back. Both groups were required to operate on bad roads and in extreme darkness. They were reunited about 10 mi (16.1 km) from Raleigh Court House around noon.[34]

At a farm 6 mi (9.7 km) west of Raleigh Court House, a two-company detachment from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry joined the brigade and brought supplies. The detachment's leader, Captain George Washington Gilmore, also brought orders from General Scammon that clarified the brigade's mission.[Note 7] The men were issued four days of rations plus three days of rations for their horses. Any men or horses determined to be unfit to continue the expedition were sent back to their home camp with the empty supply wagons. The group returning to home camp was escorted by one company from the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry.[Note 8] Thus, the brigade continued with 441 mounted infantry men, 298 men from the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry, and 79 men from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry.[38]

Tug Ridge

The brigade passed Oceana Court House in Wyoming County on July 16. On the next day, the advance guard (cavalry companies D, E, and F with Colonel Powell) was sent forward to the top of Tug Ridge. Tug Ridge is located on the north side of Abb's Valley, near the Virginia border with West Virginia. During the war, Abb's Valley was an important mountain pass monitored by rebel troops.[39] It was raining as Powell's men advanced, and they encountered a picket of six rebels who were inside a tent. A portion of the three companies led by Lieutenant Jeremiah Davidson surprised the rebels, capturing them without firing a shot.[40] About 3 mi (4.8 km) beyond the ridge, near Abbs Valley, Powell and the three companies "... dashed into Camp Pemberton, at the head of Abb's Valley, and captured 25 prisoners belonging to a home-guard company ... and 700 stand of arms, intended for arming a regiment in that vicinity."[41] Food was also captured, and redistributed among the brigade. The weapons were destroyed.[Note 9] Up until this point, the brigade captured all rebels confronted in an effort to keep its location secret. However, one rebel in the Tug Ridge-Abb's Valley region either was not captured or was captured and escaped—and warned his superiors that a large Union force was approaching.[43] A newspaper article about the raid, published a week later in Abingdon, Virginia, described the Union brigade while it was in Abb's Valley as having "a Colonel along acting as a Brigadier, but mainly commanded by a one-eyed Colonel by the name of Powell".[44]

Walker Mountain

On the evening of July 17, the brigade (and its prisoners) camped on a farm about 6 mi (9.7 km) from Tazewell Court House (Jeffersonville) and 45 mi (72.4 km) from Wytheville.[1] On the morning of July 18, they passed Burk's Garden, and some houses and weapons were burned.[29] At the foot of Walker Mountain, about 8 mi (12.9 km) from Wytheville, the brigade's rear guard was attacked by Major Andrew Jackson May's cavalry of about 150 men. The rear guard at that time was Company C from the 34th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, and it had also been assigned the task of guarding prisoners. The opposing forces had not expected a confrontation at this location, and May's force outnumbered the small group of surprised men from Ohio. May was able to free the rebel prisoners (many were from the company that had been captured in Abb's Valley) and capture Union soldiers.[45] According to the report of Confederate General John S. Williams, Toland's brigade lost 8 men killed and 20 taken prisoner.[Note 10]

About 5 mi (8.0 km) outside of Wytheville, Colonel Toland sent two companies (D and F) of cavalry west to strike the Mount Airy railroad depot.[41] The two-company detachment was led by Captain George Millard. Its purpose was to destroy railroad infrastructure and telegraph lines on the west side of Wytheville, which would prevent Confederate troops located in the Saltville region from arriving by train and reinforcing Wytheville. It was determined that the target was too strongly guarded, so the two companies rode east to rejoin the brigade. They arrived in Wytheville near the end of the fighting.[48]

The main portion of Toland's brigade arrived in Wytheville around 6:00 p.m. on July 18. The rear of the brigade was still skirmishing with Major May's men at that time.[41] After its successful clash with the rear guard, May's cavalry had pressed forward until it came upon the main body of Toland's men, about 3 mi (4.8 km) from Wytheville. May was eventually forced to retreat to the mountains, since he was now outnumbered and had no advantage in the open terrain.[49] After a small rebel skirmish line was discovered in front of the brigade near the entrance to the town, Colonel Powell and the cavalry were called forward from the rear.[1]

Confederates

The Confederate Army became aware of the Union horsemen on July 17, after one man from the 45th Virginia Infantry escaped Toland's brigade near Tug Mountain. The rebel, who either evaded capture or was captured and escaped, fled on horseback and warned Confederate headquarters.[Note 11]

Saltville

Confederate General John S. "Cerro Gordo" Williams, headquartered in Saltville, Virginia, was notified of the invading Union Army at 11:00 am (July 17) while he was visiting outposts in Tazewell County.[51] The information was passed by couriers and telegraph, and Confederate military posts throughout the region became aware of a Union army force near Tazewell Court House that was estimated to be 1,300 men. By sunrise on July 18, Williams had a cavalry unit of 250 men report for duty. This cavalry unit, which had been retrieved from adjacent counties west of Saltville, was led by Major May and Major John D. Morris. Rebel scouts were now reporting the movements of the Union army. Major May's cavalry was sent to harass the Union force until a planned junction with Confederate infantry led by Colonel William E. Peters.[51]

In addition to the headquarters of General Williams, Saltville was the home of an important salt mine that provided salt for much of the Confederate nation.[14] As the Union brigade moved in Tazewell County, the Confederate Army command became concerned about the salt works, which is located on the west side of Smyth County. For this reason, the infantry force led by Colonel Peters was moved back toward Saltville—and Major May did not receive support.[51] On the early afternoon of July 18, the situation changed: the Union expedition was moving closer to Wytheville and the lead mine located in Wythe County, just south of Wytheville in Austinville, Virginia.[52] The lead mine was a major source of lead for bullets used by the Confederate army. (Ironically, the company that ran the mine was named Union Lead Mining Company.) Lead was shipped on the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad to Richmond, Knoxville, and Chattanooga, to be made into bullets for the Confederate Army.[8]

Dublin

General Samuel Jones, commander of the Confederate Armies in southwest Virginia, was informed of the Union Army's movements beginning midday July 18.[51] Jones' headquarters was at the Dublin railroad depot—east of Wytheville along the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad.[50] Jones intercepted a passenger train on the railroad line around 3:00 pm, and the train was used to haul soldiers and equipment to Wytheville. He sent two small newly organized companies, employees from his headquarters, and some local citizens who volunteered to help. This group totaled to about 130, and was led by Major Thomas M. Bowyer.[51] Bowyer's men were well armed, and brought two pieces of artillery plus additional small weapons for the locals. The train carrying Bowyer and his men was delayed because it had to wait for an eastbound train to pass.[53]

Wytheville

The citizens of Wytheville eventually became aware of the invading Union Army. Local legend says that on July 17, a farmer in Tazewell County (located north of Wytheville) sent his daughter on a night ride to warn the town of Wytheville of the approaching Union horsemen. The young woman, Molly Tynes, rode 41 mi (66.0 km) through mountain ranges and a forest to warn the small town.[Note 12] Joseph Kent, who was working on his farm east of the town, was summoned by the town leaders. Kent was a veteran of the Mexican–American War who had fought at the First Battle of Bull Run (also known as First Manassas) before resigning and returning home.[57] Kent was called "Major Joseph F. Kent" in Bowyer's after action report.[51] Because of his military experience, Kent was asked to lead the community's defense. He held a meeting at the courthouse, and sent volunteers to Walker Mountain to serve as lookouts.[53] Many in the community panicked and fled south to the mountains (not Walker Mountain). Valuables were removed from the banks and the post office, and also moved to the mountains south of town.[58] The citizens that were willing to fight were asked to gather their weapons and reassemble at the courthouse.[53]

Bowyer and his men arrived at the train station south of Wytheville at 5:10 pm, when the Union brigade was about 1 mi (1.6 km) north of town.[59] The depot was about 0.75 miles (1.2 km) south of the center of town. The artillery was unloaded from the train, but horses could not be found to move it. Bowyer, with assistance from Kent and Abraham Umbarger from the local militia, distributed his extra small arms to the local citizens. A small line of rebels had already formed on the north side of town. By 5:30, Bowyer's men began moving from the depot toward town.[48] Bowyer wanted to bring all armed citizens to the railroad depot, where he believed he could use his artillery. Kent rejected that idea, believing they would have no chance against a quick strike from the horsemen. Kent moved his citizen volunteers into houses and buildings, while most of Bowyer's men stayed near the courthouse or at the south end of town.[60]

Raid

As the Union soldiers approached Wytheville in the early evening of July 18, the rear portion of the command was having small skirmishes with Confederate cavalry following them. About 1 mi (1.6 km) outside of Wytheville, rebels were encountered in the front. This small group of rebels was positioned along the crest of a low ridge that obscured the view into town. Colonel Powell and the cavalry were ordered from the rear to the front to charge into town. Toland's order was for the charge to be made in columns down the town's main pike that was blocked by the small group of rebels. Colonel Powell requested that Colonel Toland have the infantry dismount and drive the rebel skirmishers toward town before the charge, because he was unable to see what was behind the rebels.[1] Powell also suggested that if the cavalry were to charge, the men should be deployed "to right and left" instead of a straight ahead charge.[61] Toland "characteristically disregarded" and strongly rejected Powell's suggestions.[Note 13]

Charge

The cavalry obeyed Colonel Toland's order and charged forward in column, four abreast. The small group of rebels quickly fled into town with the Union cavalry following.[1] The charge was led by Captain Gilmore's two-company detachment from the First West Virginia Cavalry, followed by Colonel Powell and Company I of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry. A second group consisting of Company B and Company H from the 2nd West Virginia, led by Major John J. Hoffman, entered the town next. Company E served as the cavalry's rear guard.[29] The riders expected a battle line with Confederate soldiers further down the street. Instead, they discovered that the road was lined with a high stake fence, and the houses on both sides of the road were full of armed citizens of the community. Private Joseph Sutton, a member of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry and participant in the raid, described the street that led into Wytheville as "an avenue of death".[1]

As the Union cavalry approached, about half of the 120 local civilians fled south toward the railroad depot, and took positions closer to the men from the Confederate army.[65] The initial volley fired by the remaining (and nervous) locals was ineffective because it had been fired too soon.[66] The second volley, fired after a signal by Major Kent, found many in Captain Delaney's Company A. His group was fired upon by a company of Confederate soldiers in the street and from locals in the houses. One local, recalling this volley many years later, said "The colonel commanding the raiding party was killed, and the head of the column went down, men and horses in a confused mass."[65] He also said "The momentum of the column of cavalry carried many who were near the front over the dead and wounded men and horses. It was death to them to remain or hesitate. They spurred their horses forward over their dead and dying comrades and passed between our ranks as we opened out to the sidewalks. While they dashed by us firing their pistols, we continued the use of the musket. The bugle sounded the retreat, and the column of cavalrymen faced about and retired, only to re-form and come at us again."[65]

Major Kent's idea to fight from the cover of buildings was considered "an irregular but most successful combat".[67] Major Bowyer, leader of the Confederate force, said "Owing to the great advantage we secured in fighting from houses and other shelter against mounted men in the streets, we were enabled to inflict far greater loss upon the enemy than we sustained ..."[68] Although the original shooters from the town's buildings were citizens and home guard, they were eventually joined by some of the soldiers from the Confederate army.[68] A newspaper described the beginning as a "desperate fight", with the locals in the houses "shooting them down like sheep, and producing great consternation amongst them."[67]

The three Union cavalry companies leading the charge advanced into the town, but suffered casualties almost immediately.[6] Captain Delaney of Company A of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry (not a colonel) was the leader of the charge. Delaney was one of the first officers killed.[69] Both of Delaney's lieutenants were wounded—one of them (First Lieutenant William E. Guseman) mortally.[Note 14] Leaders were definitely targets. Major Hoffman, leading the remaining portion of the cavalry, was thrown over his horse after it was shot.[62] The horse was killed and the hard fall left Hoffman temporarily stunned. Although Hoffman was not killed, one newspaper report mentioned a major among the Union dead.[67] Hoffman's portion of the cavalry, along with the many casualties from the first three companies, was effectively stopped—with many of the men injured after being thrown from their horses, wounded, or killed. They were mostly caught in an open space and surrounded by a high fence and dead horses—and being shot by an enemy protected by the cover of buildings.[62] One historian wrote that the trapped cavalry men were "sitting ducks".[71] Some of the men took cover behind dead horses while others fled back up the road. Approximately 80 horses lay dead in the street.[67] Assuming the 80 horses all belonged to the cavalry, about one fifth of the cavalry became horseless. Of the 79 men in the detachment from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry, 26 were killed, missing, or wounded during the expedition. Most of those casualties occurred in Wytheville.[47] Confederate General Sam Jones claimed that the Union force "lost every one of their field officers."[72]

Reinforcements

Despite the casualties of men and horses, portions of the first three companies "began to work in earnest, flashing from one end of town to the other."[6] A request was made for reinforcements from the infantry. The infantry had been held in reserve, but "immediately dismounted" and moved forward when the 2nd West Virginia "sought safety".[73] Lieutenant Colonel Franklin wisely brought his infantry forward on the sides of the street—dismounted (as Powell preferred earlier). A company of infantry occupied one side of the pike that led into town. Portions of the trapped 2nd West Virginia, now dismounted, pushed down the fence and occupied the other side. These two groups moved forward as skirmishers to dislodge its enemy from houses and buildings.[62]

Colonels shot

During the early part of the fighting, Colonel Powell was accidentally shot in the back from friendly fire. The 2nd West Virginia Cavalry, without its two highest-ranking officers (Powell and Hoffman), became disorganized.[33] A portion of the cavalry was trapped in the open against shooters protected by buildings, and many dismounted either for their own safety or because their horse had been shot.[62] At that time, Colonel Toland hurried forward to run the leaderless dismounted cavalry. Freeman and the infantry were already further south in town. The cavalry believed their behavior was appropriate for the situation, and advised Colonel Toland to act in a similar manner. Toland, still on his horse, became an easy target for shooters from a nearby two-story brick house.[62] Despite warnings from the cavalry's Company H that he should take cover, Toland refused to dismount—saying "the bullet that can kill me has not been made". He was shot through the heart immediately after his exclamation.[74] This happened early in the fighting, and men from the 2nd West Virginia's Company H were close enough to hear the bullet strike him.[62] Thus, both colonels were eliminated from the fighting during the first 10 minutes.[19][Note 15]

With Toland dead, the severely–wounded Powell was in command of the brigade—but Powell was thought to be dying, and could not be moved. This left the infantry's Lieutenant Colonel Franklin in command, although he did not know this until the fighting was mostly over.[75] The 2nd West Virginia Cavalry did not reform and act as a regiment. It had only four companies in the town, and one was serving as the rear guard.[Note 16] Instead, individual companies were led by their captains (or lieutenants), and some of these leaders performed well.[71] Captain Gilmore led the portion of cavalry that was still mounted, including what was left of his two-company detachment from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry. Gilmore's detachment, which "suffered most severely", was complemented in the after action report made by Lieutenant Colonel Franklin. The 34th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, led by Franklin and Major John W. Shaw, also performed well.[47]

Overwhelmed

On the south side of town, a Confederate artillery crew led by Captain John M. Oliver struggled to find horses to move their two artillery pieces. Finally securing horses, they moved toward Main Street with their two large weapons. Captain Gilmore, from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry, became aware of the artillery threat, while a small group of Confederate soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Henry Bozang rushed to protect the artillery and its crew.[71] A combined force of cavalry and infantry, led by Lieutenant Abraham from Gillmore's Company, charged through Bozang's men while the artillery crew hurriedly tried to load their weapons.[76] The Confederate artillerists were able to fire one shot, but its main effect was to cause the horses still attached to the other piece of artillery to panic and pull it over. Before the remaining artillery piece could be reloaded, Abraham's men captured it while killing Oliver and two gunners. The remaining artillery crew fled. Lieutenant Bozang was wounded and his command surrendered.[77]

The 34th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, with its superiority in weapons and size, soon drove back all resistance.[71] They attacked the courthouse (Major Bowyer's command post) and surrounding buildings. After some very intense and close fighting, the Confederate soldiers—understanding that they were vastly outnumbered, their artillery had been captured, and some of the buildings were on fire—were ordered to withdraw from the town. They were to meet about 1 mi (1.6 km) south of the railroad depot at the railroad water tank, where the train had been moved for safety. When they arrived at the rendezvous point, they discovered that the railroad conductor had panicked—and left without them. They were forced to walk back to Dublin.[78]

Without the Confederate soldiers, the remaining fighters (home guard and citizens of the town) were vastly outnumbered by the invading force. Many of them dropped their weapons and fled south. The disorganized Union soldiers had trouble differentiating between innocent bystanders and fighters (unless gunpowder marks on their clothing gave them away).[77] Toland's acting Adjutant-General, Lieutenant Ezra W. Clark, ordered more buildings burned.[78] The Union soldiers began burning all buildings that had contained rebel marksmen (and markswomen), and prisoners were taken.[62] Around this time, Captain Millard's cavalry detachment arrived in Wytheville. He reported that the Mount Airy Depot was occupied by a strong Confederate Army force. It was close to 8:00 pm, and the fighting was over.[79] The report of Lieutenant Colonel Freeman Franklin said that "The loss of the enemy in killed was estimated at 75; the number of wounded unknown. We took 86 prisoners, besides 35 at Abb's Valley."[19]

Return march

Eight to ten houses were set on fire by the Union army. A small amount of damage was inflicted on the railroad line, but it was later repaired in less than an hour.[80] Later in the evening, Lieutenant Colonel Franklin began planning the brigade's next move. After consulting with Colonel Powell and regimental commanders, he determined that a return to the safety of base camp was the best alternative—especially without good intelligence on the strength of the enemy forces assumed to be moving toward Wytheville.[Note 17] The brigade left town less than 12 hours after it arrived.[Note 18]

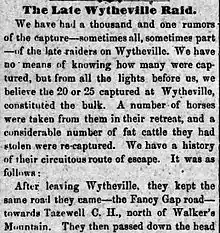

Franklin's brigade departed on the same road it used to enter Wytheville, the road that leads to Tazewell Courthouse (Jeffersonville). It was a good decision to leave, because the Confederate army had already begun an attempt to block their return home. One of the two main roads available for the return trip was occupied by troops under the command of Colonel John McCausland, and the other road was blocked by the command of Brigadier-General John S. Williams.[82] Two cavalry units were in pursuit, including Major May's cavalry that had harassed the brigade as it approached Wytheville.[Note 19]

Because of the difficult situation, the Union brigade paroled its prisoners, and continued its retreat north by obscure and winding mountain paths. Many horses "gave out" and were left on the mountain paths. Some of the worn animals fell to their deaths on the steep trails. The brigade was able to capture additional horses, so only about 100 men returned to home camp dismounted.[85] The rear guard was attacked on July 19 and 20, but repulsed its pursuers.[86] The Union brigade reached the safety of Union lines at Fayetteville on July 23, having received no rations for four days.[Note 20] Confederate Colonel McCausland believed that the retreating Union brigade should have been captured. His report said "I am also of the opinion that the cavalry force that was in Tazewell, under General Williams and Colonel May, was sufficient to have captured the enemy, if it had been properly managed."[88]

Aftermath

Franklin's report said that Union losses for the entire excursion were 11 killed, 32 wounded, 17 taken prisoner, and 26 missing. This includes 2 officers killed, 5 wounded, and 1 missing. More men would eventually die from their wounds, including Lieutenant Guseman from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry. The infantry's portion of the casualties was 4 killed, 11 wounded, 17 taken prisoner, and 10 missing.[47] Captain Gilmore's two-company cavalry detachment had the most severe losses (about one third of the men were killed or wounded), especially Company A.[Note 21] Companies B and I from the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry had fatalities in Wytheville, while Company C lost two men early in the excursion in the ambush near Piney Creek.[90] An estimated 300 horses died or were left to die.[85] Infantry leaders were critical of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry, and members of the cavalry were critical of the infantry leadership.[Note 22] Despite the losses, Union General Scammon wrote an order saying "The general commanding congratulates the troops of his command on the brilliant achievements ..."[35]

The Confederate point of view for the battle was much different from the reports of the Union officers. Confederate General Jones reported "The information I have is that the expedition started from Kanawha 1,200 or 1,300 strong, and that when it reached Fayetteville, on the return, it numbered but 500, only 300 of whom were mounted. The commander (Colonel Toland) and several other officers were killed, the second in command, Colonel Powell, and other officers wounded and captured. They admit a loss of more than 60 killed and wounded; it was probably much greater. Their dead bodies were scattered along the roads and mountain paths. Our loss, as reported to me, was 1 captain and 5 men killed, and about double that number wounded."[82] The Reverend J. M. Wharey, who fought as a citizen of Wytheville during the raid, wrote "... there was no telling what damage they would have done. Had Colonel Toland lived, the lead mines, the salt works, and the railroad bridges near Wytheville would have been at their mercy. So our little battle disconcerted their plans and the raid was a complete failure."[91]

Colonel Powell's wound to his back was judged to be fatal by surgeons for both the Union and Confederate armies. One historian believed that Powell also lost an eye in this battle, but his eye was permanently injured before the war.[Note 23] When the Union army departed from Wytheville, Powell was left behind with other wounded soldiers that could not be moved. These men became prisoners of the Confederacy. The citizens of Wytheville blamed Powell for the burning of many of the community's homes.[15] General Jones wanted Powell held accountable for the burning of two buildings from an earlier raid, and added that Powell was "... one of the most dangerous officers we have had to contend with ..."[93] For his own safety, Powell was hidden. Several local women were instrumental in preventing retaliation on the blue-coated prisoners.[15] Powell unexpectedly healed, and was eventually moved to Richmond's Libby Prison where he survived for a portion of that time in a dungeon on a bread and water diet.[94] He was exchanged for Colonel Richard H. Lee in early February 1864, and returned to the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry during March 1864.[95] Years after the fighting, the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry's Captain Fortescue (Company I), wrote "... though I was afterwards on many hotly contested fields, I was never upon any that was more so than Wytheville."[96]

See also

- West Virginia Units in the Civil War

- West Virginia in the Civil War

- Ohio in the Civil War

Notes

Footnotes

- The region suffered another major attack during the war in April 1865, when General George B. Stoneman led 4,000 cavalry troops into the area. His men attacked Wytheville (among several communities), disabled the nearby lead mine, and destroyed much of the railroad infrastructure.[12]

- As of 1862, the following states were involved with the Saltville, Virginia, salt mine: Virginia, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, and South Carolina.[14]

- The entire 2nd West Virginia Cavalry regiment did not participate in the raid. Companies initially present were B, C, D, E, F, H, and I.[19]

- The western portion of the state of Virginia became the state of West Virginia on June 20, 1863—and the 2nd Regiment of Loyal Virginia Volunteer Cavalry became known as the 2nd West Virginia Volunteer Cavalry Regiment.<ref name='<"WVState"'>"The New State of West Virginia". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved 2017-01-01.

- At the time of the American Civil War, some of the small county seats were identified with the county name followed by "Court House". For example, Beckley, Virginia (later Beckley, West Virginia) is identified in some maps as "Beckley", but in others as "Raleigh C.H." or Raleigh Court House. Beckley is the county seat of Raleigh County. Some of these smaller communities consisted of not much more than a courthouse during the 1860s.[30]

- One of the men from the cavalry wrote about the ambush, saying "This was understood to have been caused by a blunder of the commander in not providing a sufficient advance guard, thus allowing the column to be drawn into a trap."[32]

- The two-company detachment from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry was commanded by Captain George Washington Gilmore. Company A was led by Captain Dennis Delaney and the other company was led by Lieutenant James Abraham.[35] Abraham's company had been attached to the 1st West Virginia, but formed independently by Captain Gilmore at the request of General George B. McClellan. Gilmore's company (led by Abraham in this action) eventually became Company L of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry.[36] Company A in this case was not the original 1st (West) Virginia Cavalry Company A captained by J. Lowrie McGee and later Harrison H. Hagans. A report made by the state of West Virginia identifies Captain Dennis Delaney's company as Company I of the First Regiment West Virginia Cavalry Volunteers.[37]

- Using the after action report of Major John J. Hoffman, and eliminating companies that were listed in the report over the next few days, it can be determined that Company C escorted the empty supply wagons back to base camp. This is the company that was ambushed at Piney Creek. Since the original 870 men were joined by 79 men from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry, and 818 men continued on the expedition, 131 men (including dead and wounded) returned to camp.[34]

- A second account of the Abb's Valley confrontation says the J. E. Stollings infantry company of 45 men, all inside a house, was captured along with horses and 500 weapons.[42]

- The Confederate report contradicts the Union report.[46] The deaths of Colonel Toland and various members of the cavalry, added to Williams' report, would exceed Franklin's Union report—which states totals of 11 men killed, 32 wounded, 17 taken prisoner, and 26 missing for the entire expedition.[47]

- Sources are not in complete agreement on if the escapee was captured and escaped, or evaded capture. Johnson says only "... a Confederate soldier escaped to give vital information on the location of the Union Army."[50] Sutton says that, in the rain, a small cavalry group "captured the entire picket before one of them had time to get outside the tent." He says the remaining (much larger) portion of the Confederate force was in a house, which was "surrounded and all the inmates captured while they were enjoying an old Virginia hoe-down."[40] Moore says "the rebel pickets and entire camp were captured ... but one escaped who was then on horse."[18] Franklin's report says "Colonel Powell effected, capturing all but 1 man, who made his escape and gave intelligence to the enemy of our approach, the first intelligence of the kind that had preceded us."[33]

- Molly Tynes' ride was described in a 1951 Charleston newspaper article.[54] There is some doubt if she really made her ride, but a young woman named Molly Tynes was living in the area during the 1860s.[55] The after action reports filed by Confederate leaders General Samuel Jones, Major Thomas M. Bowyer, General John S. Williams, and Colonel John McCausland do not mention Molly Tynes.[51] Molly Tynes Davidson is discussed (and pictured) in a 1910 journal, which says she is buried "in the old cemetery at Tazewell." She is credited as the one who warned the community of the impending invasion.[56]

- Private Sutton of the cavalry's Company H, who participated in the raid, discusses the disagreement between Toland and Powell in his book—including Toland's strong rejection of Powell's preference.[1] The cavalry felt that it was a mistake to charge "in column, when there was plenty of open ground on each side of the road". Describing the immediate aftermath of the charge, Sutton wrote "Colonel Toland hurried forward, evidently seeing the mistake he made by charging in column ..."[62] Another author, and former officer in the 6th West Virginia Cavalry, discussed the exchange between Toland and Powell—saying Toland's orders resulted in a loss that was "heavy and totally unjustified".[63] The author of a book published more recently discussed the exchange between the two colonels, and said Powell's suggestion "... would have been the correct strategy for the situation."[60] The 2nd West Virginia Cavalry had already seen the result of a cavalry charge into a town without knowing what was waiting for them. This experience was earned in the hostile (then Virginia) town of Lewisburg. In 1862, Union leader George Crook used a small group of skirmishers to lure a Confederate cavalry charge into Lewisburg, and ambushed the Confederates after they chased the skirmishers to the other side of town. Confederate losses in Lewisburg were considerable—over 170 casualties and about 150 taken prisoner. A battalion of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry, including Major John J. Hoffman and (then) Captain William H. Powell, was used to pursue the fleeing rebels.[64]

- An 1864 account of the raid said "One volley killed Captain Delaney and his First Lieutenant, and severely wounded his Second Lieutenant ..."[6] Another source has a different description of Delaney's death. According to Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, who was not at Wytheville, Delaney's "... horse had been killed and he stood by her firing his revolver. He re-loaded after firing all his shots." Hayes also said, in a July 26 letter to Mrs. Delaney, that Delaney was shot in the head by a shooter from a second story window—possibly the same citizen that later shot Colonel Toland.[70]

- A letter written by Captain William Fortescue, of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry's Company I, has a different version of the events surrounding the two colonels. Fortescue wrote that he was the senior officer of the advance, and Captain Delaney was his junior. He said Colonel Toland gave Colonel Powell an order for a saber charge, and Toland was shot while Powell was giving Fortescue the order. Powell was shot shortly afterwards. Fortescue did not mention any friendly fire accident connected to Powell.[69]

- Companies A, G, and K from the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry were not on the Wytheville expedition.[34] Company C, which had been ambushed early in the expedition, escorted the empty supply wagons back to camp. Companies D and F had been detached by Colonel Toland, and sent to the Mount Airy depot. The remaining companies were B, E, H, and I—but Toland placed Company E on picket duty.[34]

- Private Joseph Sutton, from the cavalry, wrote that Franklin sent Lieutenant Clark to the wounded Colonel Powell for instructions around 10:00 p.m. Powell's opinion was that it was "impractical to attempt to continue the raid as planned" and that Franklin should use his best judgement to return the brigade to its camp near Charleston.[81] Franklin's regimental commanders, provided they were healthy enough, were Major Shaw for the infantry and Major Hoffman for the cavalry. Franklin wrote in his report that after "consultation with the regimental commanders, it was thought inadvisable to make any further demonstrations against the enemy."[73]

- Private Joseph Sutton wrote that the brigade left around midnight.[81] Lieutenant Colonel Franklin reported two times of departure. In one report, he said "At daylight Sunday morning [19th], we commenced our return march."[19] In another report, he wrote "... at 3 a.m., of July 19, commenced the return march."[73] Another source says that a train whistle alarmed the Union brigade, which feared Confederate reinforcements.[65]

- Among the pursuers was Company E of the 8th Virginia Cavalry, known as the Border Rangers.[83] The main pursuing forces were led by Major May and Colonel John D. Morris.[84]

- Having no rations for four days does not mean the men had no food for four days, although they had very little. There was little food in the region for foraging. Private Sutton described a portion of the command obtaining four small steers plus a small quantity of corn meal on July 21.[87]

- Captain Gilmore's detachment of two companies had 26 of 79 men killed or wounded.[36] From Captain Delaney's Company A, Delaney and First Lieutenant William E. Guseman were killed. Second Lieutenant Charles H. Livingstone was wounded and taken prisoner along with two other enlisted men. Among Company A's wounded, Franklin Funk died August 31 in a hospital, and John Gilmore's arm was amputated.[89]

- Two Union leaders were critical of the cavalry. General E. Parker Scammon, commanding the U.S. Army 3rd Division, 8th Army Corps, mentioned "the discredit which attaches to the Second Virginia Cavalry", and praised Lieutenant Colonel Franklin (commander of the infantry) for his skill in leading the return where he evaded "superior numbers of the enemy" who he "defeated with heavy loss when assailed".[43] The report of infantry Lieutenant Colonel Freeman E. Franklin says "I regret to state that the Second West Virginia Cavalry did not behave so well, but were thrown into considerable confusion, many of them dismounting and leaving their horses while they sought their own safety."[33] Men from the cavalry thought Toland did not have an advance guard at the beginning of the expedition that was large enough.[32] One former cavalry leader, writing about the beginning of the expedition, said the brigade "suffered some loss at Raleigh C. H. through lack of proper precaution, evidencing the worthlessness of temporarily mounted infantry as cavalrymen."[63] The men from the cavalry, including Colonel Powell, were also unhappy with the order to charge in column down the main street into Wytheville, especially when they were not sure what was waiting for them in the town.[1] After the fighting began, Toland joined the dismounted portion of the cavalry but remained on his horse in the street. The cavalry believed that if Toland had followed their advice to get out of the street, he would not have been killed.[62]

- One historian said "Powell received a pistol wound in his shoulder and lost an eye during Toland's Raid and was later taken to Libby Prison in Richmond."[66] However, Powell was involved with iron mills before the Civil War, and he lost the vision in his right eye after an accident at an iron mill in 1846.[92]

Citations

- Sutton 2001, p. 91

- "Welcome to Wythe County, Virginia". Wythe County, Virginia. Retrieved 2016-07-04.

- "George Wythe". The Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved 2016-07-04.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Moore 1864, p. 447

- Johnson & Wythe County Historical Society 2003, p. 3

- "Geology and the Civil War in Southwest Virginia: The Wythe County Mines" (PDF). Commonwealth of Virginia, Division of Mineral Resources (May 1996). Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- Johnson & Wythe County Historical Society 2003, p. 1

- Whisonant 2015, p. 157

- Johnson & Wythe County Historical Society 2003, pp. 25–26

- "Stoneman's Raid in Virginia". Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, Virginia Tech History Department. Retrieved 2016-06-05.

- Johnson & Wythe County Historical Society 2003, p. 4

- "Geology and the Civil War in Southwest Virginia: The Smyth County Salt Works" (PDF). Commonwealth of Virginia, Division of Mineral Resources (August 1996). Retrieved 2015-03-16.

- Whisonant 2015, p. 80

- "Dublin, VA". New River VA.com. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- Johnson & Wythe County Historical Society 2003, p. 5

- Moore 1864, p. 446

- Scott 1889, p. 943

- "Civil War Army Organization". Civil War Trust. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- Sutton 2001, p. 88

- Scott, Lazelle & Davis 1887, p. 1061

- "Campaign in the Kanawha Valley, W. Va. (September 23, 1862, report of Col. Edward Siber; and September 24, 1862, report of Colonel J. A. J. Lightburn)". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved 2015-07-22.

- Hill 2014, pp. 84–85

- Troiani, Coates & McAfee 2006, p. 16

- Troiani, Coates & McAfee 2006, pp. 1–2

- Wallace 1897, p. 189

- Lang 1895, p. 186

- "Report of Major John J. Hoffman, Second Virginia Cavalry". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- "Beckley Raleigh County Chamber of Commerce". Beckley Raleigh County Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- Sutton 2001, p. 246

- Sutton 2001, pp. 88–89

- United States Congress 1891, p. 1002

- Scott 1889, pp. 943–945

- Scott 1889, p. 941

- Livingston 1912, p. 766

- West Virginia & Adjutant General's Office 1866, p. 70

- Sutton 2001, p. 89

- Walker 1985, p. 40

- Sutton 2001, p. 90

- Scott 1889, p. 944

- Sutton 2001, pp. 90–91

- Scott 1889, p. 942

- "The Recent Raid - Further Particulars". Abingdon Virginian. 1863-07-24. p. 2.

- Walker 1985, p. 50

- Scott 1889, p. 951

- United States Congress 1891, p. 1005

- Walker 1985, p. 45

- Walker 1985, p. 51

- Johnson & Wythe County Historical Society 2003, p. 6

- Scott 1889, pp. 945–962

- Walker 1992, p. 19

- Walker 1985, p. 44

- "Raid in Virginia by Union Men Recalled in Civil War Report". Charleston Gazette. 1951-11-04. p. 27.

Wytheville Saved by Woman's Night Ride to Warn of Approach of Yankees

- "The Thrilling Ride of Mollie Tynes". Blue Ridge Institute and Museum. Retrieved 2016-03-15.

- Unlisted (Confederate Veteran) 1910, pp. 428–429

- Walker 1992, p. 21

- Johnson & Wythe County Historical Society 2003, p. 11

- Walker 1992, p. 20

- Walker 1985, p. 46

- Andrew 1910, p. 31

- Sutton 2001, p. 92

- Lang 1895, p. 187

- Sutton 2001, pp. 52–54

- Johnson 1909, p. 336

- Johnson & Wythe County Historical Society 2003, p. 18

- "Yankee Raid Upon Wytheville". Staunton Spectator. 1863-07-28. p. 2.

The result of this fight was, that the Yankees lost a Colonel, (Toland) Major, and had another Colonel (Powell) severely wounded ...

- Scott 1889, p. 949

- Pendleton 1920, p. 619

- "Diaries of Rutherford B. Hayes, Volume II, Chapter XXII, page 423". Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- Walker 1985, p. 47

- Scott 1889, p. 945

- United States Congress 1891, p. 1003

- Walker 1992, p. 22

- Walker 1992, p. 24

- Johnson & Wythe County Historical Society 2003, p. 12

- Walker 1985, p. 48

- Johnson & Wythe County Historical Society 2003, pp. 20–21

- Johnson & Wythe County Historical Society 2003, p. 23

- Scott 1889, p. 950

- Sutton 2001, p. 93

- Scott 1889, p. 947

- "War-Time Reminiscences of James D. Sedinger Company E, 8th Virginia Cavalry (Border Rangers)". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved 2016-06-01.

- Scott 1889, pp. 950–953

- Sutton 2001, p. 95

- Sutton 2001, p. 94

- Sutton 2001, pp. 94–95

- Scott 1889, p. 962

- "1st Regiment West Virginia Cavalry". Ohio Civil War Central. Retrieved 2016-07-19.

- Sutton 2001, pp. 245–250

- Johnson 1909, p. 337

- "William H. Powell Papers, 1825–1899". Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- Sutton 2001, p. 103

- Lang 1895, p. 188

- Sutton 2001, p. 112

- Walker 1985, p. 60

References

- Andrew, T. C. (1910). "The Wytheville Raid—Another Account". Confederate Veteran. Nashville, TN: S. A. Cunningham. XVIII (1). OCLC 1564663.

- Hill, John (2014). Across a Deadly Field : Regimental Rules for Large Civil War Battles. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-0259-0. OCLC 889525171.

- Johnson, John M.; Wythe County Historical Society (2003). Lead, Salt, and the Railroad : Toland's Raid on Wytheville, July 18, 1863. Wytheville, VA: Wythe County Historical Society. OCLC 53012023.

- Johnson, V. M. (1909). "Recollections of the Wytheville Raid". Confederate Veteran. Nashville, TN: S. A. Cunningham. XVII (7). OCLC 1564663.

- Lang, Joseph J. (1895). Loyal West Virginia from 1861 to 1865 : With an Introductory Chapter on the Status of Virginia for Thirty Years Prior to the War. Baltimore, MD: Deutsch Publishing Co. OCLC 779093.

- Livingston, Joel Thomas (1912). A History of Jasper County, Missouri, and its People. Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co. OCLC 2704614.

- Moore, Frank (1864). The Rebellion Record : A Diary of American Events, with Documents, Narratives, Illustrative Incidents, Poetry, Etc. New York: G.P. Putnam. OCLC 2230865.

- Pendleton, William C. (1920). History of Tazewell County and Southwest Virginia, 1748–1920. Richmond, VA: W. C. Hill Printing Co. OCLC 1652100.

- Scott, Robert N. (1889). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXVIII Part II. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 318422190.

- Scott, Robert Nicholson; Lazelle, H. M.; Davis, George B. (1887). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XIX Part 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-918678-07-2. OCLC 427057.

- Sutton, Joseph J. (2001) [1892]. History of the Second Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry Volunteers, During the War of the Rebellion. Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press. ISBN 978-0-9628866-5-2. OCLC 263148491.

- Troiani, Don; Coates, Earl J.; McAfee, Michael J. (2006). Don Troiani's Civil War Zouaves, Chasseurs, Special Branches, & Officers. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3320-5. OCLC 61859726.

- United States Congress (1891). "The Miscellaneous Documents of the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Fifty-First Congress 1889-'90". The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXVII Part II. U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 191710879. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- Unlisted (Confederate Veteran) (1910). "Girl Saved Wytheville—Toland's Raid". Confederate Veteran. Nashville, TN: S. A. Cunningham. XVII (8). OCLC 1564663.

- Walker, Gary C. (1985). The War in Southwest Virginia, 1861–65. Roanoke, VA: Gurtner Graphics & Print. Co. OCLC 12703870.

- Walker, Gary C. (1992). Civil War Tales. Roanoke, VA: A & W Enterprise. OCLC 27975601.

- Wallace, Lew (1897). The Story of American heroism : Thrilling Narratives of Personal Adventures During the Great Civil War, as Told by the Medal Winners and Roll of Honor Men. Springfield, Ohio: J. W. Jones. OCLC 11816985.

- West Virginia; Adjutant General's Office (1866). Annual Report of the Adjutant General's Office of the State of West Virginia for the year ending December 31, 1865. Wheeling: John Grew. OCLC 6742841.

- Whisonant, Robert C. (2015). Arming the Confederacy : How Virginia's Minerals Forged the Rebel War Machine. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-14508-2. OCLC 903929889.