Atlantic County, New Jersey

Atlantic County is a county located in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2010 United States Census, the county had a population of 274,549,[3] having increased by 21,997 from the 252,552 counted at the 2000 Census (+8.7%, tied for third-fastest in the state),[4][5][6] As of the 2019 Census Bureau estimate, the county's population was 263,670, making it the 15th-largest of the state's 21 counties.[7][8][9] Its county seat is the Mays Landing section of Hamilton Township.[2] The most populous place was Egg Harbor Township, with 43,323 residents at the time of the 2010 Census; Galloway Township, covered 115.21 square miles (298.4 km2), the largest total area of any municipality, though Hamilton Township has the largest land area, covering 111.13 square miles (287.8 km2).[6]

Atlantic County | |

|---|---|

Atlantic City boardwalk | |

Seal | |

Location within the U.S. state of New Jersey | |

New Jersey's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 39.47°N 74.64°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1837 |

| Named for | Atlantic Ocean[1] |

| Seat | Mays Landing[2] |

| Largest municipality | Egg Harbor Township (population) Galloway Township (total area) Hamilton Township (land area) |

| Government | |

| • County executive | Dennis Levinson (R)[lower-alpha 1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 671.83 sq mi (1,740.0 km2) |

| • Land | 555.70 sq mi (1,439.3 km2) |

| • Water | 116.12 sq mi (300.7 km2) 17.28% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 274,549 |

| • Estimate (2019) | 263,670 |

| • Density | 410/sq mi (160/km2) |

| Congressional district | 2nd |

| Website | www |

This county forms the Atlantic City–Hammonton Metropolitan Statistical Area,[10] which is also part of the Delaware Valley Combined Statistical Area.[11][12]

History

Since the 6th millennium BC, Indigenous people have inhabited New Jersey. By the 17th century, the Absegami tribe of the Unalachtigo Lenape tribe – "people near the ocean" – stayed along the streams and back bays of what is now Atlantic County. The group referred to the broader area as Scheyichbi – "land bordering the ocean".[13][14] European settlement by the Dutch, Sweden, and England contributed to the demise of the indigenous people. In 1674, West Jersey was established, and its provincial government designated the court of Burlington County in 1681, splitting off Gloucester County five years later from the southern portion. This county was bounded by the Mullica River to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, and the Great Egg Harbor River and Tuckahoe River to the south.[13] Great Egg Harbour Township, also called New Weymouth and later just Egg Harbor, was designated in 1693 from the eastern portions of Gloucester County.[13]

The region's early settlers, many of them Quakers, lived along the area's waterways. In 1695, John Somers purchased 300 acres (120 ha) of land on the northern shore of the Great Egg Harbor Bay in 1695, the same year he began ferry service across the bay to Cape May County. His son, Richard, built Somers Mansion between 1720 and 1726, which is the oldest home in existence in the county.[15] Daniel Leeds first surveyed the coastal waters of Egg Harbor in 1698, eventually finding Leeds Point.[16] In 1735 according to folklore, Mother Leeds gave birth and cursed her 13th child in Leeds Point, which became known as the Jersey Devil.[17] In the early 18th century, George May founded Mays Landing.[16]

In 1774, the northern portion of Egg Harbor Township became Galloway Township.[13] In 1785, residents in what is now Atlantic County requested to split from Gloucester County to the New Jersey legislature, wanting a local court. Mays Landing – the region's largest community at the time, had more saloons than churches. Criminals could escape custody before reaching Gloucester City on a four-day wagon ride.[18] In 1798, the western portion split off to become Weymouth Township, and in 1813, the northwestern portion partitioned to become Hamilton Township. On February 7, 1837, the New Jersey legislature designated Atlantic County from Galloway, Hamilton, Weymouth, and Egg Harbor townships,[13] choosing Mays Landing as the county seat. In the same year, the Board of Freeholders was established as the county government.[16] As of the 1830 census, the townships making up Atlantic County only had a population of 8,164, making it the least populated New Jersey county. By that time, a continuous line of houses extended from Somers Point to Absecon.[19]

Mullica Township was established from Galloway Township in 1837.[13] In 1852, Dr. Jonathan Pitney recommended Absecon Island as a health resort, and formed the Camden and Atlantic Railroad Company to construct the line from Camden to the coast. The company purchased land from Atlantic and Galloway Townships in 1853, then promoted and sold the lots. Atlantic City formed on May 1, 1854, in advance of the rail line opening on July 4 of that year.[20] In 1858, Egg Harbor City was formed from portions of Galloway and Mullica townships. In 1866, Hammonton was founded from Hamilton and Mullica townships. A year later, portions of Hamilton Township split off to become Buena Vista Township. In 1872, Absecon was split from portions of Egg Harbor and Galloway townships.[13] By 1885, more than half of the county's population lived in Atlantic City, and by 1910 this more than two-thirds of the county lived there.[14]

With more people moving to the area in the late 1800s into the early 1900s, several municipalities were created in short succession – Margate (then called South Atlantic City) in 1885, Somers Point in 1886, Pleasantville and Linwood in 1889, Brigantine in 1890, Longport in 1898, Ventnor in 1903, Northfield and Port Republic in 1905, and Folsom in 1906. On May 17, 1906, the eastern coastal boundary of Atlantic County was established. The final municipalities in the county to be created were Corbin City from Weymouth Township in 1922, Estell Manor from Weymouth Township in 1925, and Buena from Buena Township in 1948. In 1938, the county's western border was clarified with Camden and Burlington counties using geographic coordinates.[13] After a peak in prominence in the 1920s during the prohibition era, Atlantic City began declining in population in the 1950s as tourism declined. The county's growth shifted to the mainland.[14][21]

In 1973, the New Jersey Coastal Area Facilities Review Act required additional state permitting for construction in the eastern half of the county.[14] In the same ballot as the 1976 presidential election, 56.8% of New Jersey voters approved an initiative to allow legalized gambling in Atlantic City. Two years later, Resorts Atlantic City opened as the first casino in the city, and there were 15 by 1990. Since then, five have closed, including four in 2014, while two casinos – the Borgata and Ocean Resort Casino – have opened. Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Atlantic City opened in 2018, refurbishing the former Trump Taj Mahal.[22][14] In 1978, Congress created the Pinelands National Reserve, which created the Pinelands Commission and a management policy for the seven counties in the Pine Barrens, including Atlantic County.[14][23] Concurrent with the 1980 Presidential election, Atlantic County residents voted in favor to create a new state of South Jersey, along with five other counties in a nonbinding referendum.[24]

Geography

Atlantic County is located about 100 mi (160 km) south of New York City and about 60 mi (100 km) southeast of Philadelphia.[14] It is roughly 30 mi (48 km) in width by 20 mi (32 km) in height.[19] According to the 2010 Census, the county had a total area of 671.83 square miles (1,740.0 km2), including 555.70 square miles (1,439.3 km2) of land (82.7%) and 116.12 square miles (300.7 km2) of water (17.3%). It is the third largest county in New Jersey, behind Ocean County and Burlington County.[6][25]

The county lies along the Atlantic Coastal Plain, with sea level and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Adjacent to the coast are three barrier islands – Absecon Island (Which contains Atlantic City, Ventnor, Margate, and Longport), Brigantine Island, and Little Beach.[14] To the west of the barrier islands, 4 mi (6 km) stretch of marshlands, inlets, and waterways connect and form the Intracoastal Waterway.[26][19] Beneath the county is a mile of clay and sand that contains the Kirkwood–Cohansey aquifer, which supplies fresh groundwater for all of the streams and rivers in the region. The interior of the county is part of the Pine Barrens, which covers the southern third of New Jersey, and is prone to forest fires. Lowland areas are swampy and contain pitch pine or white cedar trees. Upland areas in the west of the county are hilly, containing oak and pine trees.[14] The highest elevation in the county – about 150 ft (46 m) above sea level – is found near the border with Camden County, just west of Hammonton.[27] The county's western boundary with Burlington and Camden counties, clarified in 1761, is a manmade line about halfway between the Atlantic Ocean and the Delaware Bay.[13]

Adjacent counties

Atlantic County borders the following counties:[28]

- Burlington County – north

- Camden County – northwest

- Cape May County – south

- Cumberland County – southwest

- Gloucester County – northwest

- Ocean County – northeast

Climate

| Mays Landing, New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In recent years, average temperatures in the county seat of Mays Landing have ranged from a low of 24 °F (−4 °C) in January to a high of 86 °F (30 °C) in July, although a record low of −11 °F (−24 °C) was recorded in February 1979 and a record high of 106 °F (41 °C) was recorded in June 1969. Average monthly precipitation ranged from 2.99 inches (76 mm) in February to 4.21 inches (107 mm) in March.[29]

The county has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa). Average monthly temperatures in central Atlantic City range from 33.9 °F in January to 75.2 °F in July, while in Folsom they range from 32.7 °F in January to 76.3 °F in July.

In December 1992, a nor'easter produced the highest tide on record in Atlantic City, 9.0 ft (2.7 m) above mean lower low water.[30] Former Hurricane Sandy struck near Brigantine as an extratropical cyclone, which produced an all-time minimum barometric pressure of 948.5 mbar (28.01 inHg) and wind gusts to 91 mph (146 km/h) in Atlantic City, as well as a storm surge that inundated low-lying areas. Three people died in the county during the storm, and damage was estimated at $300 million (2012 USD).[31][30]

National protected areas

- Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge covers 47,000 acres (19,000 ha) of coastal habitat in Atlantic and Ocean counties.[32]

- Great Egg Harbor Scenic and Recreational River runs from Camden County to Great Egg Harbor.[33]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 8,726 | — | |

| 1850 | 8,961 | 2.7% | |

| 1860 | 11,786 | 31.5% | |

| 1870 | 14,093 | 19.6% | |

| 1880 | 18,704 | 32.7% | |

| 1890 | 28,836 | 54.2% | |

| 1900 | 46,402 | 60.9% | |

| 1910 | 71,894 | 54.9% | |

| 1920 | 83,914 | 16.7% | |

| 1930 | 124,823 | 48.8% | |

| 1940 | 124,066 | −0.6% | |

| 1950 | 132,399 | 6.7% | |

| 1960 | 160,880 | 21.5% | |

| 1970 | 175,043 | 8.8% | |

| 1980 | 194,119 | 10.9% | |

| 1990 | 224,327 | 15.6% | |

| 2000 | 252,552 | 12.6% | |

| 2010 | 274,549 | 8.7% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 263,670 | [34] | −4.0% |

| Historical sources: 1790-1990[35] 1970-2010[6] 2000[4] 2010[3] 2000-2010[36] | |||

Census 2010

The 2010 United States Census counted 274,549 people, 102,847 households, and 68,702 families in the county. The population density was 494.1 per square mile (190.8/km2). There were 126,647 housing units at an average density of 227.9 per square mile (88.0/km2). The racial makeup was 65.40% (179,566) White, 16.08% (44,138) Black or African American, 0.38% (1,050) Native American, 7.50% (20,595) Asian, 0.03% (92) Pacific Islander, 7.36% (20,218) from other races, and 3.24% (8,890) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 16.84% (46,241) of the population.[3]

Of the 102,847 households, 29.8% had children under the age of 18; 45.6% were married couples living together; 15.5% had a female householder with no husband present and 33.2% were non-families. Of all households, 26.9% were made up of individuals and 10.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.61 and the average family size was 3.17.[3]

23.3% of the population were under the age of 18, 9.3% from 18 to 24, 24.6% from 25 to 44, 28.7% from 45 to 64, and 14.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39.9 years. For every 100 females, the population had 94.2 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 91 males.[3]

Census 2000

As of the 2000 United States Census[37] there were 252,552 people, 95,024 households, and 63,190 families residing in the county. The population density was 450 people per square mile (174/km2). There were 114,090 housing units at an average density of 203 per square mile (79/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 68.36% White, 17.63% Black or African American, 0.26% Native American, 5.06% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 6.06% from other races, and 2.58% from two or more races. 12.17% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[4][38] Among those residents listing their ancestry, 18.3% were of Italian, 17.3% Irish, 13.8% German and 7.7% English ancestry.[38][39]

There were 95,024 households, out of which 31.70% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.50% were married couples living together, 14.80% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.50% were non-families. 27.00% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.70% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.59 and the average family size was 3.16.[4]

In the county, the population was spread out, with 25.30% under the age of 18, 8.10% from 18 to 24, 30.60% from 25 to 44, 22.40% from 45 to 64, and 13.60% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females there were 93.60 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.20 males.[4]

The median income for a household in the county was $43,933, and the median income for a family was $51,710. Males had a median income of $36,397 versus $28,059 for females. The per capita income for the county was $21,034. About 7.6% of families and 10.50% of the population were below the poverty line, including 12.8% of those under age 18 and 10.50% of those age 65 or over.[38][40]

Government and politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 46.0% 64,438 | 52.7% 73,808 | 1.3% 1,785 |

| 2016 | 44.6% 52,690 | 51.6% 60,924 | 3.8% 4,427 |

| 2012 | 41.0% 46,522 | 57.9% 65,600 | 1.1% 1,222 |

| 2008 | 41.9% 49,902 | 56.9% 67,830 | 1.3% 1,517 |

| 2004 | 46.6% 49,487 | 52.5% 55,746 | 0.8% 864 |

| 2000 | 39.1% 35,593 | 58.0% 52,880 | 2.9% 2,629 |

| 1996 | 35.3% 29,538 | 53.2% 44,434 | 11.5% 9,629 |

| 1992 | 38.0% 34,279 | 43.9% 39,633 | 18.2% 16,386 |

| 1988 | 56.3% 44,748 | 42.9% 34,047 | 0.8% 647 |

| 1984 | 59.3% 49,158 | 40.1% 33,240 | 0.6% 453 |

| 1980 | 49.8% 37,973 | 41.1% 31,286 | 9.1% 6,943 |

| 1976 | 45.6% 36,733 | 52.1% 41,965 | 2.4% 1,932 |

| 1972 | 59.5% 45,667 | 36.8% 28,203 | 3.7% 2,830 |

| 1968 | 42.2% 32,807 | 45.7% 35,581 | 12.1% 9,446 |

| 1964 | 32.9% 25,626 | 65.3% 50,945 | 1.9% 1,448 |

| 1960 | 50.9% 39,158 | 46.9% 36,129 | 2.2% 1,682 |

| 1956 | 65.7% 44,698 | 31.9% 21,668 | 2.5% 1,672 |

| 1952 | 58.0% 40,259 | 41.7% 28,953 | 0.2% 163 |

| 1948 | 54.4% 31,608 | 43.6% 25,313 | 2.0% 1,150 |

| 1944 | 46.7% 25,593 | 52.9% 28,972 | 0.4% 229 |

| 1940 | 45.7% 30,551 | 54.1% 36,155 | 0.1% 92 |

| 1936 | 38.2% 24,680 | 61.2% 39,605 | 0.6% 403 |

| 1932 | 51.9% 31,264 | 46.6% 28,071 | 1.5% 926 |

| 1928 | 66.0% 37,238 | 33.9% 19,152 | 0.1% 75 |

| 1924 | 73.6% 27,936 | 18.3% 6,937 | 8.1% 3,066 |

| 1920 | 76.6% 21,245 | 20.8% 5,753 | 2.6% 727 |

| 1916 | 62.9% 9,713 | 35.4% 5,467 | 1.7% 267 |

| 1912 | 31.7% 4,422 | 35.0% 4,885 | 33.3% 4,656 |

| 1908 | 63.7% 8,822 | 33.1% 4,578 | 3.2% 448 |

| 1904 | 70.4% 7,933 | 27.2% 3,064 | 2.4% 268 |

| 1900 | 67.7% 6,122 | 28.4% 2,566 | 4.0% 358 |

| 1896 | 66.0% 5,005 | 29.4% 2,233 | 4.4% 338 |

| County CPVI: D+2 | |||

In 1974, Atlantic County voters changed the county governmental form under the Optional County Charter Law to the County executive form. Atlantic County joins Bergen, Essex, Hudson and Mercer counties as one of the five of 21 New Jersey counties with an elected executive.[42] The charter provides for a directly elected executive and a nine-member Board of Chosen Freeholders, responsible for legislation. The executive is elected to a four-year term and the freeholders are elected to staggered three-year terms, of which four are elected from the county on an at-large basis and five of the freeholders represent equally populated districts.[43][44] In 2016, freeholders were paid $20,000 a year, while the freeholder chairman was paid an annual salary of $21,500.[45]

As of 2018, Atlantic County's Executive is Republican Dennis Levinson, whose term of office ends December 31, 2019.[46] He had previously won election in 1999, 2003, 2007 and 2011.[47]

Members of the Board of Chosen Freeholders are:[43][48]

- Chairman Frank D. Formica, Freeholder At-Large (R, 2018, Margate City)[49]

- Vice Chairwoman Maureen Kern, Freeholder District 2, including Atlantic City (part), Egg Harbor Township (part), Linwood, Longport, Margate City, Northfield, Somers Point and Ventnor City (R, 2018, Somers Point)[50]

- James A. Bertino, Freeholder District 5, including Buena, Buena Vista Township, Corbin City, Egg Harbor City, Estell Manor, Folsom, Hamilton Township (part), Hammonton, Mullica Township and Weymouth Township (R, 2018, Hammonton)[51]

- Ernest D. Coursey, Freeholder District 1, including Atlantic City (part), Egg Harbor Township (part) and Pleasantville (D, 2019, Atlantic City)[52]

- Richard R. Dase, Freeholder District 4, including Absecon, Brigantine, Galloway Township and Port Republic (R, 2019, Galloway Township)[53]

- Caren L. Fitzpatrick, Freeholder At-Large (D, 2020, Linwood)[54]

- Amy L. Gatto, Freeholder At-Large (R, 2019, Mays Landing in Hamilton Township)[55]

- John W. Risley, Freeholder At-Large (R, 2020, Egg Harbor Township)[56]

Pursuant to Article VII Section II of the New Jersey State Constitution, each county in New Jersey is required to have three elected administrative officials known as "constitutional officers." These officers are the County Clerk and County Surrogate (both elected for five-year terms of office) and the County Sheriff (elected for a three-year term).[57] Atlantic County's constitutional officers are:[58]

- County Clerk Edward P. McGettigan (D, 2021, Linwood)[59][60]

- Sheriff Eric Scheffler (D, 2021, Northfield)[61][62]

- Surrogate James Curcio (R, 2020, Hammonton)[63][64]

The Atlantic County Prosecutor is Damon G. Tyner of Egg Harbor Township, who took office in March 2017 after being nominated the previous month by Governor of New Jersey Chris Christie and receiving confirmation from the New Jersey Senate.[65][66]

Atlantic County, along with Cape May County, is part of Vicinage 1 of New Jersey Superior Court. The Atlantic County Civil Courthouse Complex is in Atlantic City, while criminal cases are heard in May's Landing; the Assignment Judge for Vicinage 1 is Julio L. Mendez.[67]

The 2nd Congressional District covers all of Atlantic County.[68][69] For the 116th United States Congress, New Jersey's Second Congressional District is represented by Jeff Van Drew (R, Dennis Township).[70]

The county is part of the 1st, 2nd, 8th and 9th Districts in the New Jersey Legislature.[71] For the 2020–2021 session (Senate, General Assembly), the 1st Legislative District of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Mike Testa (R, Vineland) and in the General Assembly by Antwan McClellan (R, Ocean City) and Erik K. Simonsen (R, Lower Township).[72][73] For the 2018–2019 session (Senate, General Assembly), the 2nd Legislative District of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Chris A. Brown (R, Ventnor City) and in the General Assembly by Vince Mazzeo (D, Northfield) and John Armato (D, Buena Vista Township).[74][75] For the 2018–2019 session (Senate, General Assembly), the 8th Legislative District of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Dawn Marie Addiego (R, Evesham Township) and in the General Assembly by Joe Howarth (R, Evesham Township) and Ryan Peters (R, Hainesport Township).[76][77] For the 2018–2019 session (Senate, General Assembly), the 9th Legislative District of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Christopher J. Connors (R, Lacey Township) and in the General Assembly by DiAnne Gove (R, Long Beach Township) and Brian E. Rumpf (R, Little Egg Harbor Township).[78][79]

Politics

In state and national elections, Atlantic County is a reliably Democratic county, in contrast to the other three counties on the Jersey Shore -- Monmouth, Ocean and Cape May counties—which tend to lean heavily Republican.

As of August 1, 2020, there were a total of 195,965 registered voters in Atlantic County, of whom 71,142 (36.3%) were registered as Democrats, 52,513 (26.8%) were registered as Republicans and 69,466 (35.5%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 2,844 (1.5%) voters registered to other parties.[80] Among the county's 2010 Census population, 62.5% were registered to vote, including 76.7% of those ages 18 and over.[81][82]

In the 2016 presidential election, Democrat Hillary Clinton received 60,924 votes (51.0%) in the county, ahead of Republican Donald Trump with 52,690 votes (44.1%), and other candidates with 3,677 (3.1%). In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 65,600 votes (57.9%) in the county, ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 46,522 votes (41.1%) and other candidates with 1,057 votes (0.9%), among the 113,231 ballots cast by the county's 172,204 registered voters, for a turnout of 65.8%.[83][84] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 67,830 votes (56.5%) in Atlantic County, ahead of Republican John McCain with 49,902 votes (41.6%) and other candidates with 1,310 votes (1.1%), among the 120,074 ballots cast by the county's 176,316 registered voters, for a turnout of 68.1%.[85] In the 2004 presidential election, Democrat John Kerry received 55,746 votes (52.0%), ahead of Republican George W. Bush with 49,487 votes (46.2%) and other candidates with 864 votes (0.8%), among the 107,187 ballots cast by the county's 153,496 registered voters, for a turnout of 69.8%.[86]

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 43,975 votes in the county (60.0%), ahead of Democrat Barbara Buono with 25,557 votes (34.9%) and other candidates with 947 votes (1.3%), among the 73,258 ballots cast by the county's 176,696 registered voters, yielding a 41.5% turnout.[87][88] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 35,724 votes (47.7%), ahead of Democrat Jon Corzine with 33,361 votes (44.5%), Independent Chris Daggett with 3,611 votes (4.8%) and other candidates with 913 votes (1.2%), among the 74,915 ballots cast by the county's 166,958 registered voters, yielding a 44.9% turnout.[89]

Economy

Based on data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, Atlantic County had a gross domestic product (GDP) of $12.9 billion in 2018, which was ranked 15th in the state and represented an increase of 3.5% from the previous year.[90]

When Atlantic County was first established in 1837, its sparse population subsided on clams, oysters, and fishing. An early industry was shipbuilding, using the sturdy oak trees of the Pine Barrens.[19] Bog iron furnaces opened in the early 1800s, but declined by the 1850s due to the growth of the Philadelphia iron industry. Around this time, several people and cotton mills opened. The first railroad across the county opened in 1854, intended to assist the bog iron industry; instead, it spurred development in Atlantic City, as well as the growth of farming towns.[14] Farmers began growing grapes, cranberries, and blueberries.[21] The competition dropped the price of travel to 50¢, affordable for Philadelphia's working class.[91] Travelers often brought their lunch in shoe boxes, leading to their nickname "shoobies".[92]

Legalized gambling and the growth of the casino industry employed more than 34,145 people as of 2012.[22]

Breweries, distilleries, and wineries

In 1864, Louis Nicholas Renault brought property in Egg Harbor City and opened Renault Winery, the oldest active winery in New Jersey, and third-oldest in the United States. During the prohibition era, the winery obtained a government permit to sell wine tonic for medicinal purposes.[93][94][95] Tomasello Winery grew its first vineyard in 1888, and opened to the public in 1933. Gross Highland Winery operated in Absecon from 1934 to 1987, when it was sold to developers. Balic Winery opened in 1966 in Mays Landing,[96] although its vineyards date back to the early 19th century.[97] Sylvin Farms Winery opened in 1985 in Egg Harbor City.[98] In 2001, Bellview Winery opened in the Landisville section of Buena.[99] A year later, DiMatteo Vineyards opened in Hammonton,[100] and in 2007, Plagido's Winery opened in the same town.[101]

In 1998, Tun Tavern Brewery opened in Atlantic City across from the Atlantic City Convention Center, named after the original Tun Tavern in Philadelphia, which was the oldest brew house in the country, opening in 1685.[102] In 2015, Tuckahoe Brewing moved from Ocean View to a facility in Egg Harbor Township capable of producing four times the amount of beer.[103] Garden State Beer Company opened in 2016 in Galloway.[104] In 2018, Hidden Sands Brewery opened in Egg Harbor Township.[105]

In 2014, Lazy Eye Distillery opened in Richland in Buena Vista Township.[106] Little Water Distillery opened in Atlantic City in 2016.[107]

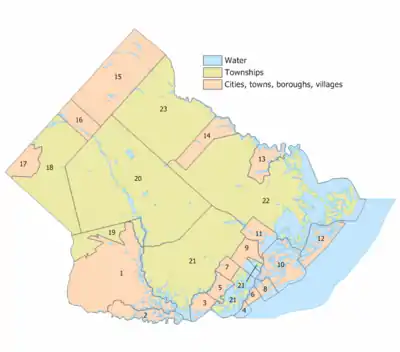

Municipalities

Municipalities in Atlantic County (with 2010 Census data for population, housing units and area) are:[108]

| Municipality (with map key) |

Map key | Mun. type |

Pop. | Housing units |

Total area |

Water area |

Land area |

Pop. density |

Housing density |

School district | Communities[109] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absecon | 11 | City | 8,411 | 3,365 | 7.29 | 1.90 | 5.40 | 1558.8 | 623.6 | Pleasantville (9-12) (S/R) Absecon (PK-8) | |

| Atlantic City | 10 | City | 39,558 | 20,013 | 17.04 | 6.29 | 10.75 | 3680.8 | 1862.2 | Atlantic City | |

| Brigantine | 12 | City | 9,450 | 9,222 | 10.36 | 3.98 | 6.39 | 1479.5 | 1443.8 | Atlantic City (9-12) (S/R) Brigantine (PK-8) | |

| Buena | 17 | Borough | 4,603 | 1,855 | 7.58 | 0.00 | 7.58 | 607.4 | 244.8 | Buena | Landisville Minotola |

| Buena Vista Township |

18 | Township | 7,570 | 3,008 | 41.53 | 0.47 | 41.05 | 184.4 | 73.3 | Buena | Collings Lakes CDP (1,706) East Vineland Milmay Newtonville Richland |

| Corbin City | 2 | City | 492 | 212 | 8.94 | 1.28 | 7.67 | 64.2 | 27.7 | Ocean City (9-12) (S/R) Upper Township (K-8) (S/R) | |

| Egg Harbor City | 14 | City | 4,243 | 1,736 | 11.44 | 0.51 | 10.93 | 388.1 | 158.8 | Greater Egg Harbor (9-12) Egg Harbor City (PK-8) | Clarks Landing |

| Egg Harbor Township |

21 | Township | 43,323 | 16,347 | 74.93 | 8.34 | 66.6 | 650.5 | 245.5 | Egg Harbor Township | Bargaintown English Creek Jeffers Landing |

| Estell Manor | 1 | City | 1,735 | 673 | 55.10 | 1.78 | 53.32 | 32.5 | 12.6 | Buena (9-12) (S/R) Estell Manor (K-8) | Hunters Mill |

| Folsom | 16 | Borough | 1,885 | 717 | 8.44 | 0.24 | 8.2 | 229.8 | 87.4 | Hammonton (9-12) (S/R) Folsom (PK-8) | Penny Pot |

| Galloway Township |

22 | Township | 37,349 | 14,132 | 115.21 | 26.14 | 89.07 | 419.3 | 158.7 | Greater Egg Harbor (9-12) Galloway Township (PK-8) | Absecon Highlands Cologne Conovertown Germania Leeds Point Oceanville Pomona CDP (7,124) Smithville CDP (7,242) |

| Hamilton Township |

20 | Township | 26,503 | 10,196 | 113.07 | 1.94 | 111.13 | 238.5 | 91.8 | Greater Egg Harbor (9-12) Hamilton Township (PK-8) | Mays Landing CDP (2,135) McKee City Mizpah |

| Hammonton | 15 | Town | 14,791 | 5,715 | 41.42 | 0.53 | 40.89 | 361.8 | 139.8 | Hammonton | Da Costa Dutchtown |

| Linwood | 5 | City | 7,092 | 2,798 | 4.24 | 0.38 | 3.87 | 1834.9 | 723.9 | Mainland Regional (9-12) Linwood (PK-8) | |

| Longport | 4 | Borough | 895 | 1,656 | 1.56 | 1.17 | 0.39 | 2323.7 | 4299.4 | Ocean City (9-12) (S/R) Margate (K-8) (S/R) | |

| Margate City | 6 | City | 6,354 | 7,114 | 1.63 | 0.22 | 1.42 | 4490.3 | 5027.4 | Atlantic City (9-12) (S/R) Margate (K-8) | |

| Mullica Township |

23 | Township | 6,147 | 2,360 | 56.9 | 0.48 | 56.42 | 108.9 | 41.8 | Greater Egg Harbor (9-12) Mullica Township (PK-8) | Elwood CDP (1,437) Nesco, Sweetwater |

| Northfield | 7 | City | 8,624 | 3,260 | 3.44 | 0.04 | 3.40 | 2533.7 | 957.8 | Mainland Regional (9-12) Northfield (K-8) | |

| Pleasantville | 9 | City | 20,249 | 7,219 | 7.30 | 1.60 | 5.69 | 3556.5 | 1267.9 | Pleasantville | |

| Port Republic | 13 | City | 1,115 | 444 | 8.58 | 1.10 | 7.48 | 149.0 | 59.3 | Greater Egg Harbor (9-12) (S/R) Port Republic (K-8) | |

| Somers Point | 3 | City | 10,795 | 5,556 | 5.16 | 1.13 | 4.03 | 2678.8 | 1378.7 | Mainland Regional (9-12) Somers Point (PK-8) | |

| Ventnor City | 8 | City | 10,650 | 7,829 | 3.52 | 1.57 | 1.95 | 5457.4 | 4011.8 | Atlantic City (9-12) (S/R) Ventnor (PK-8) | |

| Weymouth Township |

19 | Township | 2,715 | 1,220 | 12.45 | 0.36 | 12.09 | 224.6 | 100.9 | Buena (9-12) (S/R) Weymouth Township (PK-8) | Dorothy, Weymouth |

Health resources and utilities

Education

Institutions of higher education in Atlantic County include:

- Atlantic Cape Community College in Mays Landing serves students from both Atlantic and Cape May counties, having been created in 1964 as the state's second county college.[110] Rutgers University offers an off-site program at Atlantic Cape Community College that allows students with an associate degree from an accredited college to earn a bachelor's degree from Rutgers.[111]

- Stockton University, in Pomona, was established to provide a four-year college serving the South Jersey area.[112]

Health and police services

AtlantiCare is the largest non-casino employer, with a staff of over 5,500 people over five counties, established in 1993 by the Atlantic City Medical Center Board of Governors. Atlantic City Hospital opened in 1898, becoming Atlantic City Medical Center in 1973. Two years later, the hospital built its Mainland Division in Pomona.[113] AtlantiCare has also opened four urgent care centers.[114] In 1928, Dr. Charles Ernst and Dr. Frank Inksetter built Atlantic Shores Hospital and Sanitarium in Somers Point as a private institute for the treatment of alcohol and drug dependency. In 1940, citizens turned the facility into the not-for-profit Shore Medical Center, which has expanded over time to add more beds and units.[115][116]

In 1840, the first county jail opened in Mays Landing, designed by Thomas Ustick Walter, who also designed the U.S. Capital building. This facility was replaced by newer facilities in 1932, 1962, and the current Gerard L. Gormley Justice Facility in 1985, which can hold 1,000 inmates. The facility has controlled by the Atlantic County Department of Public Safety since 1987.[18][117]

Transportation

The indigenous people of New Jersey developed a series of trails across the state, including one from current-day Absecon to Camden.[13] Early transportation relied on the region's waterways. An early coastal road was constructed in 1716 from Somers Point to Nacote Creek in Port Republic. Roads into the county's interior were slow, unreliable, and muddy, with one main roadway along the Mullica River that eventually connected to Burlington. Roads later connected the region's industries in the 19th century,[21] until the county's first railroad opened in 1854, which brought more people to the region.[19] By 1870, the Camden and Atlantic Railroad Company carried 417,000 people each year. Also in that year, the Pleasantville and Atlantic Turnpike opened, crossing Beach Thorofare into Atlantic City.[21] A railroad competitor, the Philadelphia and Atlantic City Railway, opened in 1877 after only 90 days of construction.[20] Other rail lines connected farms and cities throughout the county by the end of the 19th century.[21] A notable railroad tragedy occurred on October 28, 1906, when three train cars derailed on a draw bridge into 30 ft (9.1 m) deep water in Beach Thorofare, killing 53 people, with only two survivors.[118] Improved roads reduced the reliance on railroads by the 1950s.[21]

In the late 1800s, a bridge opened in Mays Landing, providing road access to the county's interior.[119] The first car in Atlantic City was seen in 1899. By the 1890s, visitors began riding bicycles in the coastal resort towns, and thousands of people would ride from Camden to the coast on weekends.[21] Amid pressure from motorists and cyclists, the county improved the conditions of the roads in the early 20th century. The first road bridge to Atlantic City opened in 1905, using Albany Avenue on what is now US 40/322. In 1916, the causeway that is now New Jersey Route 152 opened between Somers Point and Longport. In 1919, the White Horse Pike (US 30) was completed from Atlantic City to Camden, and repaved through the county in 1925. Also in 1922, the Harding Highway (US 40) opened from Pennsville Township to Atlantic City, named after then-President Warren G. Harding.[91] In 1928, the Beesley's Point Bridge opened, replacing the ferry between Somers Point and Cape May County.[119] The Black Horse Pike (US 322) opened in 1935, connecting Atlantic City to Camden. Most of the county's older bridges were replaced over time, although the oldest still in existence is a swing bridge from 1904 that crosses Nacote Creek in Port Republic.[21][91] The Great Egg Harbor Bridge opened in 1956, marking the completion of the Garden State Parkway, which connected Cape May and Atlantic counties, continuing to North Jersey.[119] In 1964, the Atlantic City Expressway opened between the Parkway and Camden County, and a year later was extended into Atlantic City. In 2001, the Atlantic City–Brigantine Connector was built, connecting the Expressway with Atlantic City's marina district.[120]

As early as 1990, the South Jersey Transportation Authority had plans to construct an Atlantic County Beltway as a limited-access road, beginning along Ocean Heights Avenue in southern Egg Harbor Township at a proposed Exit 32 with the Garden State Parkway. The proposed road would pass west of the Atlantic City Airport and reconnect with the Parkway at Exit 44 via County Route 575 in Galloway Township. The routing was later truncated from U.S. 40 (the Black Horse Pike) to Exit 44 on the Parkway. The project was considered "desirable" but was not funded.[121][122]

Roads and highways

As of 2010, the county had a total of 1,930.77 miles (3,107.27 km) of roadways, of which 1,357.05 miles (2,183.96 km) were maintained by the local municipality, 372.63 miles (599.69 km) by Atlantic County and 143.50 miles (230.94 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation and 57.59 miles (92.68 km) by either the New Jersey Turnpike Authority or South Jersey Transportation Authority.[123]

Major highways

Major roadways include the Garden State Parkway (with 21.5 miles (34.6 km) of roadway in the county), the Atlantic City Expressway (29.6 miles (47.6 km)), U.S. Route 9, U.S. Route 30, U.S. Route 40, U.S. Route 206 and U.S. Route 322, as well as Route 49, Route 50, Route 52, Route 54, Route 87 and Route 152.[124][125]

Public transportation

NJ Transit's Atlantic City Line connects the Atlantic City Rail Terminal in Atlantic City with the 30th Street Station in Philadelphia, with service at intermediate stations at Hammonton, Egg Harbor City and Absecon in the county.[126][127]

Notes

- Term ends December 31, 2019.

References

- Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed October 30, 2017.

- New Jersey County Map, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed July 10, 2017.

- DP1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data for Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 30, 2013.

- DP-1 - Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000; Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data for Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed January 21, 2013.

- NJ Labor Market Views Archived September 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, March 15, 2011. Accessed October 7, 2013.

- New Jersey: 2010 - Population and Housing Unit Counts; 2010 Census of Population and Housing, p. 6, CPH-2-32. United States Census Bureau, August 2012. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- State & County QuickFacts - Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed March 24, 2018.

- Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2017 - 2017 Population Estimates Archived February 13, 2020, at Archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed March 24, 2018.

- GCT-PEPANNCHG: Estimates of Resident Population Change and Rankings: July 1, 2016 to July 1, 2017 - State -- County / County Equivalent from the 2017 Population Estimates for New Jersey Archived February 13, 2020, at Archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed March 24, 2018.

- May 2012 Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Area Definitions, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed May 29, 2013.

- May 2012 Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Area Definitions, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed October 7, 2013.

- Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas, Office of Management and Budget, February 28, 2013. Accessed October 7, 2013.

- John P. Snyder (1969). The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968 (PDF). Trenton, New Jersey: Bureau of Geology and Topography.

- "Atlantic County Master Plan" (PDF). Government of Atlantic County. October 2000. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "A Short History of Somers Point" (PDF). Somers Point Historical Society. 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- "History of Atlantic County". Government of Atlantic County. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- Carol Johnson; David Munn. "Jersey Devil - Fact or Fiction?". Atlantic County Library. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- "A Brief History of The Atlantic County Sheriff's Office". Atlantic County Sheriff. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- John Warner Barber (1844). Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey: Containing a General Collection of the Most Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, Etc., Relating to Its History and Antiquities, with Geographical Descriptions of Every Township in the State. B. Olds. pp. 63–64.

atlantic county sparse population 1850s.

- "How the Railroads came to Margate" (PDF). The Beacon. The Margate Public Library. 10 (3): 1, 6. July 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 27, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- New Jersey Historic Bridge Survey (PDF). A. G. Lichtenstein & Associates (Report). New Jersey Department of Transportation. September 1994. pp. 85–92. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "History of Casino Gambling in Atlantic City". Atlantic County Library. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "CMP Summary". State of New Jersey Pinelands Commission. Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- Erik Larson (March 5, 2016). "South Jersey voted to secede from NJ". Asbury Park Press. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- "Census 2010 U.S. Gazetteer Files: New Jersey Counties" (TXT). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- Peter L. Griffes (2004). "Intercoastal Waterway". Atlantic Boating Almanacs: Sandy Hook, NJ To St. Johns River, Fl & Bermuda. Atlantic Boating Almanac. 3. pp. 161, 174–175. ISBN 9781577855033.

- "Atlantic County High Point, New Jersey". Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "Areas touching Atlantic County". MapIt. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- Monthly Averages for Mays Landing, New Jersey, The Weather Channel. Accessed October 13, 2012.

- "High Wind Event". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- Blake, Eric S; Kimberlain, Todd B; Berg, Robert J; Cangialosi, John P; Beven II, John L (February 12, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Sandy: October 22 – 29, 2012 (PDF) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- Edwin P. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Accessed October 24, 2017. "Welcome to the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, where more than 47,000 acres of southern New Jersey coastal habitats are actively protected and managed for wildlife and for you."

- Great Egg Harbor River, United States National Park Service. Accessed October 24, 2017. "Starting as a trickle near Berlin, NJ, the River gradually widens as it picks up the waters of 17 tributaries on its way to Great Egg Harbor and the Atlantic Ocean. Established by Congress in 1992, nearly all of this 129-mile river system rests within the Pinelands National Reserve."

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- Forstall, Richard L. Population of states and counties of the United States: 1790 to 1990 from the Twenty-one Decennial Censuses, pp. 108-109. United States Census Bureau, March 1996. ISBN 9780934213486. Accessed October 7, 2013.

- U.S. Census Bureau Delivers New Jersey's 2010 Census Population Totals, United States Census Bureau, February 3, 2011. Accessed February 5, 2011.

- U.S. Census website, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Tables DP-1 to DP-4 from Census 2000 for Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau, backed up by the Internet Archive as of May 18, 2011. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- DP-2 - Profile of Selected Social Characteristics: 2000 from the Census 2000 Summary File 3 (SF 3) - Sample Data for Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 30, 2013.

- DP-3 - Profile of Selected Economic Characteristics: 2000 from Census 2000 Summary File 3 (SF 3) - Sample Data for Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 30, 2013.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- Rinde, Meir. "Explainer: What's a Freeholder? NJ's Unusual County Government System", NJ Spotlight, October 27, 2015. Accessed February 25, 2018. "Five counties -- Atlantic, Bergen, Essex, Hudson, and Mercer -- opted for popularly elected county executives in addition to freeholder boards."

- Atlantic County Board of Chosen Freeholders, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed October 21, 2017.

- District Map, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed October 21, 2017.

- Gallo Jr., Bill. "Which N.J. county freeholders are paid the most?", NJ.com, March 11, 2016. Accessed October 25, 2017. "Freeholder chairman: $21,500; Other freeholders: $20,000"

- County Executive, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- Hurley, Harry. "Dennis Levinson seeks his fifth term as Atlantic County executive" Archived 2018-02-23 at the Wayback Machine, Shore News Today, July 21, 2015. Accessed June 5, 2018. "Levinson went on to win the elections of 1999, 2003, 2007 and 2011, consistently by very wide margins."

- Atlantic County Manual 2017, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- Frank D. Formica, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- Maureen Kern, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- James A. Bertino, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- Ernest D. Coursey, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- Richard R. Dase, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- Caren L. Fitzpatrick, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- Amy L. Gatto, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- John W. Risley, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- New Jersey State Constitution (1947), Article VII, Section II, Paragraph 2, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed October 26, 2017.

- Constitutional Officers, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- Meet the Atlantic County Clerk Archived October 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Atlantic County Clerk. Accessed October 21, 2017.

- Members List: Clerks, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- Sheriff Eric Scheffler, Atlantic County Sheriff's Office. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- Members List: Sheriffs, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- Surrogate's Office, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed October 21, 2017.

- Members List: Surrogates, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- Meet the Prosecutor, Office of the Atlantic County Prosecutor. Accessed October 2, 2017. "Prosecutor Damon G. Tyner was appointed as the Atlantic County Prosecutor on March 15, 2017 by the Governor of New Jersey with the advice and consent of the State Senate."

- "Governor Chris Christie Files Nomination", Governor of New Jersey Chris Christie, press release dated February 28, 2017. "Atlantic County Prosecutor - Nominate for appointment the Honorable Damon Tyner (Egg Harbor Township, Atlantic)"

- Atlantic/Cape May Counties, New Jersey Courts. Accessed October 21, 2017.

- 2012 Congressional Districts by County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections. Accessed October 2, 2013.

- Plan Components Report, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 23, 2011. Accessed October 2, 2013.

- Directory of Representatives: New Jersey, United States House of Representatives. Accessed January 3, 2019.

- 2011 Legislative Districts by County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections. Accessed October 2, 2013.

- Legislative Roster 2020–2021 Session, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed April 16, 2020.

- District 1 Legislators, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed April 16, 2020.

- Legislative Roster 2018-2019 Session, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 21, 2018.

- District 2 Legislators, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 22, 2018.

- Legislative Roster 2018-2019 Session, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 22, 2018.

- District 8 Legislators, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 22, 2018.

- Legislative Roster 2018-2019 Session, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 22, 2018.

- District 9 Legislators, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 22, 2018.

- "Politics of New Jersey", Wikipedia, August 25, 2020, retrieved September 20, 2020

- Statewide Voter Registration Summary Archived 2014-12-22 at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, as of October 31, 2014. Accessed May 11, 2015.

- GCT-P7: Selected Age Groups: 2010 - State -- County / County Equivalent from the 2010 Census Summary File 1 for New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 11, 2015.

- Presidential November 6, 2012 General Election Results - Atlantic County Archived December 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, March 15, 2013. Accessed December 24, 2014.

- Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast November 6, 2012 General Election Results - Atlantic County Archived December 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, March 15, 2013. Accessed December 24, 2014.

- 2008 Presidential General Election Results: Atlantic County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 23, 2008. Accessed December 24, 2014.

- 2004 Presidential Election: Atlantic County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 13, 2004. Accessed December 24, 2014.

- 2013 Governor: Atlantic County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, January 29, 2014. Accessed December 24, 2014.

- Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast November 5, 2013 General Election Results : Atlantic County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, January 29, 2014. Accessed December 24, 2014.

- 2009 Governor: Atlantic County Archived 2016-01-12 at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 31, 2009. Accessed December 24, 2014.

- Local Area Gross Domestic Product, 2018, Bureau of Economic Analysis, released December 12, 2019. Accessed December 12, 2019.

- Steven Lemongello (July 17, 2011). "Historian: Atlantic City was built by the railroad". Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- Susan Tischler. "The Excursionists: A Ticket to Success". Cape May Magazine. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- Jacqueline L. Urgo (December 20, 2015). "Historic New Jersey winery works to stay open". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on August 7, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Joseph Federico; Matthew McHenry (2011). Galloway Township. Arcadia Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 9780738574110.

- Charles Hammell (August 30, 1981). "Sherry to Champagne State's Wineries Produce It". The New York Times. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Hudson Cattell (2014). Wines of Eastern North America: From Prohibition to the Present—A History and Desk Reference. Cornell University Press. p. 288. ISBN 9780801469008.

- Kevin Post (December 21, 2012). "Old winery, new location in Vineland". Press of Atlantic City.

- Hope Gruzlovic (March 20, 1998). "Sylvin Farms Wins 1998 Governor's Cup". New Jersey Department of Agriculture. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- Paul Tonnacci (May 20, 2015). "Bellview Winery has great history, awesome summer music". Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- "Guide To South Jersey Wineries". CBS3 Philadelphia. July 7, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- Lee Procida (February 4, 2011). "Outcome of federal court case could sour New Jersey's wine industry". Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- Pamela Dollak (September 24, 2014). "Take in Tun Tavern - A.C.'s historic brew house". Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Nicholas Huba (October 21, 2015). "Tuckahoe Brewing moves to bigger digs in Egg Harbor Township". Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Ray Schweibert (April 6, 2015). "A.C. Beer and Music Fest is the total entertainment package". Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Bill Barlow (January 15, 2018). "Hidden Sands Brewing Co. opens in Egg Harbor Township". Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Michael Miller (June 28, 2015). "New distillery opens in Wildwood". Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- "Little Water opens as Atlantic City's first legal distillery". The Philadelphia Inquirer. November 30, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- GCT-PH1: Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County -- County Subdivision and Place from the 2010 Census Summary File 1 for Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed January 18, 2014.

- Locality Search Archived 2016-07-09 at the Wayback Machine, State of New Jersey. Accessed May 11, 2015.

- History, Atlantic Cape Community College. Accessed October 2, 2013.

- Rutgers Off Campus - Atlantic Cape, Rutgers University. Accessed October 28, 2013.

- History, Stockton University. Accessed October 21, 2017.

- "About AtlantiCare". AtlantiCare. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- "Locations & Hours". AtlantiCare. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- Pamela Dollak (February 25, 2016). "A 75-year history". Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- Shore Medical Center 2015 Annual Report (Report). September 7, 2016. Issuu.com. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- "Division of Adult Detention (Atlantic County Jail)". Government of Atlantic County. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- Edgar A. Haine (1993). Railroad Wrecks. Cornwall Books. pp. 68–70. ISBN 9780845348444.

- "The Garden State Parkway Crossing the Great Egg Harbor Bay" (PDF). New Jersey Turnpike Authority. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- "History & Milestones". South Jersey Transportation Authority. 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- Memorandum of Understanding between the New Jersey Expressway Authority and the New Jersey Pinelands Commission (PDF) (Report). December 19, 1990.

- NJ Route 52 (1) Causeway Between City of Somers Point, Atlantic County, and Ocean City, Cape May County Draft Environmental Impact Statement (PDF) (Report). United States Department of Transportation. August 2000. III-62, III-77, III-89, III-116, III-118, III-130, IV-II, I-13. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- Atlantic County Mileage by Municipality and Jurisdiction, New Jersey Department of Transportation, May 2010. Accessed December 23, 2013.

- Fast Facts About Atlantic County, Atlantic County, New Jersey. Accessed October 21, 2017.

- Atlantic County Road Map, New Jersey Department of Transportation. Accessed December 1, 2019.

- Atlantic City Rail Line, NJ Transit. Accessed December 24, 2013.

- South Jersey Transit Guide Archived 2018-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, Cross County Connection, as of April 1, 2010. Accessed May 11, 2015.