Apple III

The Apple III (styled as apple ///) is a business-oriented personal computer produced by Apple Computer and released in 1980. Running the Apple SOS operating system, it was intended as the successor to the Apple II series, but was largely considered a failure in the market. It was designed to provide key features business users wanted in a personal computer: a true typewriter-style upper/lowercase keyboard (the Apple II only supported uppercase) and an 80-column display.

| |

| Developer | Apple Computer |

|---|---|

| Release date | November 1980[1] |

| Introductory price | US$4,340 – $7,800 (equivalent to $13,470 – $24,200 in 2019)[2] |

| Discontinued | April 1984 |

| Operating system | Apple SOS |

| CPU | Synertek 6502B @ 1.8 MHz |

| Memory | 128 kB of RAM, expandable to 512 kB |

| Predecessor | Apple II |

| Successor | Apple III Plus |

Work on the Apple III started in late 1978 under the guidance of Dr. Wendell Sander. It had the internal code name of "Sara", named after Sander's daughter.[3] The system was announced on May 19, 1980 and released in late November that year.[1] Serious stability issues required a design overhaul and a recall of the first 14,000 machines produced. The Apple III was formally reintroduced on November 9, 1981.[1][4]

Damage to the computer's reputation had already been done and it failed to do well commercially. Development stopped and the Apple III was discontinued on April 24, 1984, and its last successor, the III Plus, was dropped from the Apple product line in September 1985.[3]

An estimated 65,000–75,000 Apple III computers were sold.[4][3] The Apple III Plus brought this up to approximately 120,000.[3] Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak stated that the primary reason for the Apple III's failure was that the system was designed by Apple's marketing department, unlike Apple's previous engineering-driven projects.[5] The Apple III's failure led Apple to reevaluate its plan to phase out the Apple II, prompting the eventual continuation of development of the older machine. As a result, later Apple II models incorporated some hardware and software technologies of the Apple III, such as the thermal Apple Scribe printer.

Overview

Design

Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs expected hobbyists to purchase the Apple II, but because of VisiCalc and Disk II, small businesses purchased 90% of the computers.[6] The Apple III was designed to be a business computer and successor. Though the Apple II contributed to the inspirations of several important business products, such as VisiCalc, Multiplan, and Apple Writer, the computer's hardware architecture, operating system, and developer environment are limited.[7] Apple management intended to clearly establish market segmentation by designing the Apple III to appeal to the 90% business market, leaving the Apple II to home and education users. Management believed that "once the Apple III was out, the Apple II would stop selling in six months", Wozniak said.[6]

The Apple III is powered by a 1.8-megahertz Synertek 6502A or B[8] 8-bit CPU and, like some of the later machines in the Apple II family, uses bank switching techniques to address memory beyond the 6502's traditional 64 kB limit, up to 256 kB in the III's case. Third-party vendors produced memory upgrade kits that allow the Apple III to reach up to 512 kB of random-access memory (RAM). Other Apple III built-in features include an 80-column, 24-line display with upper and lowercase characters, a numeric keypad, dual-speed (pressure-sensitive) cursor control keys, 6-bit (DAC) audio, and a built-in 140-kilobyte 5.25-inch floppy disk drive. Graphics modes include 560x192 in black and white, and 280x192 with 16 colors or shades of gray. Unlike the Apple II, the Disk III controller is part of the logic board.

The Apple III is the first Apple product to allow the user to choose both a screen font and a keyboard layout: either QWERTY or Dvorak. These choices cannot be changed while programs were running, unlike the Apple IIc, which has a keyboard switch directly above the keyboard, allowing the user to switch on the fly.

Software

_(8249708093).jpg.webp)

The Apple III introduced an advanced operating system called Apple SOS, pronounced "apple sauce". Its ability to address resources by name allows the Apple III to be more scalable than the Apple II's addressing by physical location such as PR#6, CATALOG, D1. Apple SOS allows the full capacity of a storage device to be used as a single volume, such as the Apple ProFile hard disk drive, and it supports a hierarchical file system. Some of the features and code base of Apple SOS were later adopted into the Apple II's ProDOS and GS/OS operating systems, as well as Lisa 7/7 and Macintosh system software.

With a starting price between $4,340 to $7,800, the Apple III was more expensive than many of the CP/M-based business computers that were available at the time.[2] Few software applications other than VisiCalc are available for the computer;[9] according to a presentation at KansasFest 2012, fewer than 50 Apple III-specific software packages were ever published, most shipping when the III Plus was released.[10] Because Apple did not view the Apple III as suitable for hobbyists, it did not provide much of the technical software information that accompanies the Apple II.[9] Originally intended as a direct replacement to the Apple II series, it was designed to be backward compatible with Apple II software. However, since Apple did not want to encourage continued development of the II platform, Apple II compatibility exists only in a special Apple II Mode which is limited in its capabilities to the emulation of a basic Apple II Plus configuration with 48 kB of RAM. Special chips were intentionally added to prevent access from Apple II Mode to the III's advanced features such as its larger amount of memory.[6]

Peripherals

The Apple III has four expansion slots, a number that inCider in 1986 called "miserly".[11] Apple II cards are compatible but risk violating government RFI regulations, and require Apple III-specific device drivers; BYTE stated that "Apple provides virtually no information on how to write them". As with software, Apple provided little hardware technical information with the computer[9] but Apple III-specific products became available, such as one that made the computer compatible with the Apple IIe.[11] Several new Apple-produced peripherals were developed for the Apple III. The original Apple III has a built-in real-time clock, which is recognized by Apple SOS. The clock was later removed from the "revised" model, and was instead made available as an add-on.

Along with the built-in floppy drive, the Apple III can also handle up to three additional external Disk III floppy disk drives. The Disk III is only officially compatible with the Apple III. The Apple III Plus requires an adaptor from Apple to use the Disk III with its DB-25 disk port.[12]

With the introduction of the revised Apple III a year after launch, Apple began offering the ProFile external hard disk system.[13] Priced at $3,499 for 5 MB of storage, it also required a peripheral slot for its controller card.

Backward compatibility

The Apple III has the built-in hardware capability to run Apple II software. In order to do so, an emulation boot disk is required that functionally turns the machine into a standard 48-kilobyte Apple II Plus, until it is powered off. The keyboard, internal floppy drive (and one external Disk III), display (color is provided through the 'B/W video' port) and speaker all act as Apple II peripherals. The paddle and serial ports can also function in Apple II mode, however with some limitations and compatibility issues.

Apple engineers added specialized circuity with the sole purpose of blocking access to its advanced features when running in Apple II emulation mode. This was done primarily to discourage further development and interest in the Apple II line, and to push the Apple III as its successor. For example, no more than 48 kB of RAM can be accessed, even if the machine has 128 kB of RAM or higher present. Many Apple II programs require a minimum of 64 kB of RAM, making them impossible to run on the Apple III. Similarly, access to lowercase support, 80 columns text, or its more advanced graphics and sound are blocked by this hardware circuitry, making it impossible for even skilled software programmers to bypass Apple's lockout. A third party company, Titan Technologies, sold an expansion board called the III Plus II that allows Apple II mode to access more memory, a standard game port, and with a later released companion card, even emulate the Apple IIe.

Certain Apple II slot cards can be installed in the Apple III and used in native III-mode with custom written SOS device drivers, including Grappler Plus and Liron 3.5 Controller.

Revisions

Once the logic board design flaws were discovered, a newer logic board design was produced – which includes a lower power requirement, wider traces, and better-designed chip sockets.[13] The $3,495 revised model also includes 256 kB of RAM as the standard configuration.[13] The 14,000 units of the original Apple III sold were returned and replaced with the entirely new revised model.

Apple III Plus

Apple discontinued the III in October 1983 because it violated FCC regulations, and the FCC required the company to change the redesigned computer's name.[14][15] It introduced the Apple III Plus in December 1983 at a price of US$2,995. This newer version includes a built-in clock, video interlacing, standardized rear port connectors, 55-watt power supply, 256 kB of RAM as standard, and a redesigned, Apple IIe-like keyboard.[13][15]

Owners of the Apple III could purchase individual III Plus upgrades, like the clock and interlacing feature,[15] and obtain the newer logic board as a service replacement. A keyboard upgrade kit, dubbed "Apple III Plus upgrade kit" was also made available – which included the keyboard, cover, keyboard encoder ROM, and logo replacements. This upgrade had to be installed by an authorized service technician.

Design flaws

According to Wozniak, the Apple III "had 100 percent hardware failures".[6] Former Apple executive Taylor Pohlman stated that:[16]

There was way too short a time frame in manufacturing and development. When the decision was made to announce, there were only three Apple IIIs in existence, and they were all wire-wrapped boards.

The case of the Apple III had long since been set in concrete, so they had a certain size logic board to fit the circuits on ... They went to three different outside houses and nobody could get a layout that would fit on the board.

They used the smallest line circuit boards that could be used. They ran about 1,000 of these boards as preproduction units to give to the dealers as demonstration units. They really didn't work ... Apple swapped out the boards. The problem was, at this point there were other problems, things like chips that didn't fit. There were a million problems that you would normally take care of when you do your preproduction and pilot run. Basically, customers were shipped the pilot run.

Steve Jobs insisted on the idea of having no fan or air vents, in order to make the computer run quietly. Jobs would later push this same ideology onto almost all Apple models he had control of, from the Apple Lisa and Macintosh 128K to the iMac.[17] To allow the computer to dissipate heat, the base of the Apple III was made of heavy cast aluminum, which supposedly acts as a heat sink. One advantage to the aluminum case was a reduction in RFI (Radio Frequency Interference), a problem which had plagued the Apple II series throughout its history. Unlike the Apple II series, the power supply was mounted – without its own shell – in a compartment separate from the logic board. The decision to use an aluminum shell ultimately led to engineering issues which resulted in the Apple III's reliability problems. The lead time for manufacturing the shells was high, and this had to be done before the motherboard was finalized. Later, it was realized that there was not enough room on the motherboard for all of the components unless narrow traces were used.

Many Apple IIIs were thought to have failed due to their inability to properly dissipate heat. inCider stated in 1986 that "Heat has always been a formidable enemy of the Apple ///",[11] and some users reported that their Apple IIIs became so hot that the chips started dislodging from the board, causing the screen to display garbled data or their disk to come out of the slot "melted". BYTE wrote, "the integrated circuits tended to wander out of their sockets".[9] It is has been rumored Apple advised customers to tilt the front of the Apple III six inches above the desk and then drop it to reseat the chips as a temporary solution.[3] Other analyses blame a faulty automatic chip insertion process, not heat.[18]

Case designer Jerry Manock denied the design flaw charges, insisting that tests proved that the unit adequately dissipated the internal heat. The primary cause, he claimed, was a major logic board design problem. The logic board used "fineline" technology that was not fully mature at the time, with narrow, closely spaced traces.[19] When chips were "stuffed" into the board and wave-soldered, solder bridges would form between traces that were not supposed to be connected. This caused numerous short circuits, which required hours of costly diagnosis and hand rework to fix. Apple designed a new circuit board with more layers and normal-width traces. The new logic board was laid out by one designer on a huge drafting board, rather than using the costly CAD-CAM system used for the previous board, and the new design worked.

Earlier Apple III units came with a built-in real time clock. The hardware, however, would fail after prolonged use.[9] Assuming that National Semiconductor would test all parts before shipping them, Apple did not perform this level of testing. Apple was soldering chips directly to boards and could not easily replace a bad chip if one was found. Eventually, Apple solved this problem by removing the real-time clock from the Apple III's specification rather than shipping the Apple III with the clock pre-installed, and then sold the peripheral as a level 1 technician add-on.[3]

BASIC

Microsoft and Apple each developed their own versions of BASIC for the Apple III. Apple III Microsoft BASIC was designed to run on the CP/M platform available for the Apple III. Apple Business BASIC shipped with the Apple III. Donn Denman ported Applesoft BASIC to SOS and reworked it to take advantage of the extended memory of the Apple III.

Both languages introduced a number of new or improved features over Applesoft BASIC. Both languages replaced Applesoft's single-precision floating-point variables using 5-byte storage with the somewhat-reduced-precision 4-byte variables, while also adding a larger numerical format. Apple III Microsoft BASIC provides double-precision floating-point variables, taking 8 bytes of storage,[20] while Apple Business BASIC offers an extra-long integer type, also taking 8 bytes for storage.[21] Both languages also retain 2-byte integers, and maximum 255-character strings.

Other new features common to both languages include:

- Incorporation of disk-file commands within the language.

- Operators for MOD and for integer-division.

- An optional ELSE clause in IF...THEN statements.

- HEX$() function for hexadecimal-format output.

- INSTR function for finding a substring within a string.

- PRINT USING statement to control format of output. Apple Business BASIC had an option, in addition to directly specifying the format with a string expression, of giving the line number where an IMAGE statement gave the formatting expression, similar to a FORMAT statement in FORTRAN.

Some features work differently in each language:

| Apple III Microsoft BASIC | Apple Business BASIC | |

|---|---|---|

| integer division operator | \ (backslash) | DIV |

| reading the keyboard without waiting | INKEY$ function returns a one-character string representing the last key pressed, or the null string if no new key pressed since last reading | KBD read-only "reserved variable" returns the ASCII code of the last key pressed; the manual fails to document what is returned if no new key pressed since last reading |

| reassigning a portion of a string variable | MID$() assignment statement | SUB$() assignment statement |

| determining position of text output | POS() function to read horizontal screen position, and LPOS() function to read horizontal position on printer | HPOS and VPOS assignable "reserved variables" to read or set the horizontal or vertical position for text screen output |

| accepting hexadecimal-format values | "&H"-formatted expressions | TEN() function to give numerical value from string representing hexadecimal |

| result of ASC("")

(null string operand) |

causes an error | returns the value −1 |

Microsoft BASIC additional features

- INPUT$() function to replace Applesoft's GET command.

- LINE INPUT statement to input an entire line of text, regardless of punctuation, into a single string variable.

- LPRINT and LPRINT USING statements to automatically direct output to paper.

- LSET and RSET statements to left- or right-justify a string expression within a given string variable's character length.

- OCT$() function for output, and "&"- or "&O"-formatted expressions, for manipulating octal notation.

- SPACE$() function for generating blank spaces outside of a PRINT statement, and STRING$() function to do likewise with any character.

- WHILE...WEND statements, for loop structures built on general Boolean conditions without an index variable.

- Bitwise Boolean (16-bit) operations (AND, OR, NOT), with additional operators XOR, EQV, IMP.

- Line number specification in the RESTORE command.

- RESUME options of NEXT (to skip to the statement after that which caused the error) or a specified line number (which replaces the idea of exiting error-handling by GOTO-line, thus avoiding Applesoft II's stack error problem).

- Multiple parameters in user-defined (DEF FN) functions.

- A return to the old Applesoft One concept of having multiple USR() functions at different addresses, by establishing ten different USR functions, numbered USR0 to USR9, with separate DEF USRx statements to define the address of each. The argument passed to a USRx function can be of any specific type, including string. The returned value can also be of any type, by default the same type as the argument passed.

There is no support for graphics provided within the language, nor for reading analog controls or buttons; nor is there a means of defining the active window of the text screen.

Business BASIC additional features

Apple Business BASIC eliminates all references to absolute memory addresses. Thus, the POKE command and PEEK() function were not included in the language, and new features replaced the CALL statement and USR() function. Functionality of certain features in Applesoft that had been achieved with various PEEK and POKE locations is now provided by:

- BUTTON() function to read game-controller buttons

- WINDOW statement to define the active window of the text screen by its coordinates

- KBD, HPOS, and VPOS system variables

External binary subroutines and functions are loaded into memory by a single INVOKE disk-command that loads separately-assembled code modules. A PERFORM statement is then used to call an INVOKEd procedure by name, with an argument-list. INVOKEd functions would be referenced in expressions by EXFN. (floating-point) or EXFN%. (integer), with the function name appended, plus the argument-list for the function.

Graphics are supported with an INVOKEd module, with features including displaying text within graphics in various fonts, within four different graphics modes available on the Apple III.

Reception

[W]e probably put $100 million in advertising, promotion, and research and development into a product that was 3 percent of our revenues. In that same time frame, think what we could have done to improve the Apple II, or how much could have been done by Apple to give us products in IBM's market.

Despite devoting the majority of its R&D to the Apple III and so ignoring the II that for a while dealers had difficulty in obtaining the latter,[22] the III's technical problems made marketing the computer difficult. Ed Smith, who after the APF Imagination Machine became a distributor's representative, described the computer as "a complete disaster". He recalled that he "was responsible for going to every dealership, setting up the Apple III in their showroom, and then explaining to them the functions of the Apple III, which in many cases didn’t really work".[23] Pohlman said that Apple was only selling 500 units a month by late 1981, mostly as replacements. The company was able to raise monthly sales to 5,000, but the IBM PC's successful launch encouraged software companies to develop for it instead, causing Apple to shift focus to the Lisa and Macintosh.[16] The PC almost ended sales of the III, the most comparable Apple computer;[24] by early 1984, sales were only to existing III owners, Apple itself—its 4500 employees had about 3000-4500 units—and some small businesses.[14][15] Apple discontinued the Apple III series on April 24, 1984, four months after introducing the III Plus, after selling 65,000-75,000 computers and replacing 14,000 defective units.[25]

Jobs said that the company lost "infinite, incalculable amounts" of money on the Apple III.[25] Wozniak estimated that Apple had spent $100 million on the III, instead of improving the II and better competing against IBM.[6] Pohlman claimed that there was a "stigma" at Apple associated with having contributed to the computer. Most employees who worked on the III reportedly left Apple.[16]

Legacy

The file system and some design ideas from Apple SOS, the Apple III's operating system, were part of Apple ProDOS and Apple GS/OS, the major operating systems for the Apple II series following the demise of the Apple III, as well as the Apple Lisa, which was the de facto business-oriented successor to the Apple III. The hierarchical file system influenced the evolution of the Macintosh: while the original Macintosh File System (MFS) was a flat file system designed for a floppy disk without subdirectories, subsequent file systems were hierarchical. By comparison, the IBM PC's first file system (again designed for floppy disks) was also flat and later versions (designed for hard disks) were hierarchical.

In popular culture

At the start of the Walt Disney Pictures film TRON, lead character Kevin Flynn (played by Jeff Bridges) is seen hacking into the ENCOM mainframe using an Apple III.[26]

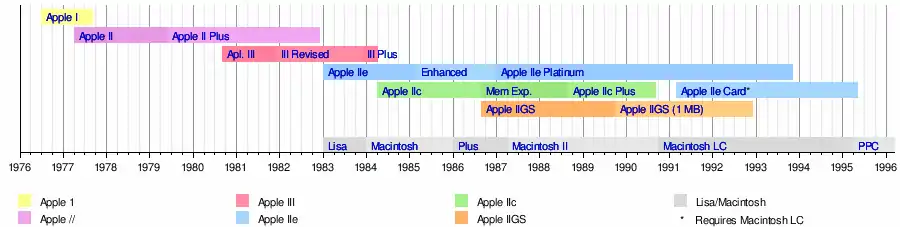

Timeline of Apple II family models

References

- Linzmayer 2004, pp. 41–42.

- VAW: Pre-PowerPC Profile Specs Archived February 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Linzmayer 2004, pp. 41–43.

- Stenger, Steven. "Apple III". oldcomputers.net.

- Wozniak, S. G. (2006). iWoz: From Computer Geek to Cult Icon: How I Invented the Personal Computer, Co-Founded Apple, and Had Fun Doing It. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-06143-4. OCLC 502898652.

- Williams, Gregg; Moore, Rob (January 1985). "The Apple Story / Part 2: More History and the Apple III". BYTE (interview). United States: UBM Technology Group. 10 (1): 167. ISSN 0360-5280. OCLC 637876171.

- "The Apple III Project". Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- Dennis J. Grimes, Brian W. Kelly (1983). Personal Computer Buyers Guide: With Exclusive Product Reference Guide. Ballinger Publishing Company. pp. I-5. ISBN 978-0-884-10917-4. OCLC 1019542512.

- Moore, Robin (September 1982). "The Apple III and Its New Profile". BYTE. 7 (9). United States: UBM Technology Group. p. 92. ISSN 0360-5280. OCLC 637876171. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- Maginnis, Mike (May 25, 2012). Apple III: A Closer Look. Event occurs at 31:42 – via YouTube.

- Obrien, Bill (September 1986). "And II For All". inCider. pp. 38, 94–95. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- "Archived - Floppy Disk Drives: Apple III Plus External Drive Adapter". Apple. February 19, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- "Apple III". Bott.org.

- Mace, Scott (April 9, 1984). "Apple IIe Sales Surge as IIc is Readied". InfoWorld. 6 (15). United States: IDG. pp. 54–55. ISSN 0199-6649. OCLC 421861736. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- Shea, Tom (January 23, 1984). "Apple releases overhauled III as the III Plus". InfoWorld. 6 (4). United States: IDG. p. 17. ISSN 0199-6649. OCLC 923931674. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- Bartimo, Jim (December 10, 1984). "Q&A: Taylor Pohlman". InfoWorld. 6 (50). United States: IDG. p. 41. ISSN 0199-6649. OCLC 923931674. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- Estes, Bob (May 15, 2009). "First Cool, Now Quiet". On-Screen Scientist.

- "What Really Killed the Apple III". AppleLogic.

- Brunner, Robert; Manock, Jerry (November 13, 2007). Apple Industrial Designers Robert Brunner and Jerry Manock. Computer History Museum. Catalog number 102695056.

- Apple III Microsoft BASIC Reference Manual, Microsoft Corporation, 1982

- Apple Business BASIC Reference Manual, Apple Computer, Inc., 1981

- McMullen, Barbara E.; John F. (February 21, 1984). "Apple Charts The Course For IBM". PC Magazine. 3 (3). Ziff Davis. p. 122. ISSN 0888-8507. OCLC 805084898. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- Edwards, Benj (February 22, 2017). "VC&G Anthology Interview: Ed Smith, Black Video Game and Computer Pioneer". Vintage Computing and Games.

- Pollack, Andrew (March 27, 1983). "Big I.B.M. Has Done It Again". The New York Times. p. Section 3, Page 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- LEM Staff (October 6, 2013). "Apple III Chaos: Apple's First Failure". Low End Mac. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- "1980: Apple III Business Computer".

The picture above is 07:31 into Side 1 of the CED movie TRON, where Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges) is using an Apple III at home...

- Sources

- Linzmayer, Owen W. (2004). "Apple III Fiasco". Apple Confidential 2.0: The Definitive History of the World's Most Colorful Company. No Starch Press. pp. 41–44. ISBN 9781593270100. OCLC 921280642.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apple III. |