Anthracotheriidae

Anthracotheriidae is a paraphyletic family of extinct, hippopotamus-like artiodactyl ungulates related to hippopotamuses and whales. The oldest genus, Elomeryx, first appeared during the middle Eocene in Asia. They thrived in Africa and Eurasia, with a few species ultimately entering North America during the Oligocene. They died out in Europe and Africa during the Miocene, possibly due to a combination of climatic changes and competition with other artiodactyls, including pigs and true hippopotamuses.[3] The youngest genus, Merycopotamus, died out in Asia during the late Pliocene. The family is named after the first genus discovered, Anthracotherium, which means "coal beast", as the first fossils of it were found in Paleogene-aged coal beds in France. Fossil remains of the anthracothere genus were discovered by the Harvard University and Geological Survey of Pakistan joint research project (Y-GSP) in the well-dated middle and late Miocene deposits of the Pothohar Plateau in northern Pakistan.[4]

| Anthracotheriidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Anthracotherium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Suborder: | Whippomorpha |

| Family: | †Anthracotheriidae Leidy, 1869 |

| Subfamilies and genera[1][2] | |

|

† Anthracotheriinae

† Bothriodontinae

† Microbunodontinae | |

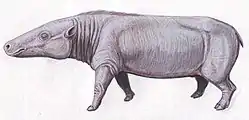

In life, the average anthracothere would have resembled a skinny hippopotamus with a comparatively small, narrow head and most likely pig-like in general appearance.[5] They had four or five toes on each foot, and broad feet suited to walking on soft mud. They had full sets of about 44 teeth with five semicrescentric cusps on the upper molars,[3] which, in some species, were adapted for digging up the roots of aquatic plants.[6]

Evolutionary relationships

Some skeletal characters of anthracotheres suggest they are related to hippos.[7] The nature of the sediments in which they are fossilized implies they were amphibious, which supports the view, based on anatomical evidence, that they were ancestors of the hippopotamuses.[8] In many respects, especially the anatomy of the lower jaw, Anthracotherium, as with other members of the family, is allied to the hippopotamus, of which it is probably an ancestral form.[9] However, one study suggests, instead of anthracotheres, another pig-like group of artiodactyls, called palaeochoerids, are the true stem group of Hippopotamidae.[10]

Recent evidence, gained from comparative gene sequencing, further suggests that hippos are the closest living relatives of whales,[11][12] so, if anthracotheres are stem hippos, they would also be related to whales in a clade provisionally called Whippomorpha.

However, the earliest known anthracotheres appear in the fossil record in the middle Eocene, well after the archaeocetes had taken up totally aquatic lifestyles. Although phylogenetic analyses of molecular data on extant animals strongly support the notion that hippopotamids are the closest relatives of cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises), the two groups are unlikely to be closely related when extant and extinct artiodactyls are analyzed. Cetaceans originated about 50 million years ago in south Asia, whereas the family Hippopotamidae is only 15 million years old, and the first hippopotamids are only 6 million years old. Yet, analyses of fossil clades have not resolved the issue of cetacean relations.[13]

Another study has offered a suggestion that anthracotheres are part of a clade that also consists of entelodonts (and even Andrewsarchus) and that is a sister clade to other cetancodonts, with Siamotherium as the most basal member of the clade Cetacodontamorpha.[14]

References

- Kron, D.G., B.; Manning, E. (1998). "Anthracotheriidae". In Janis, C.M.; Scott, K.M.; Jacobs, L.L. (eds.). Evolution of Tertiary mammals of North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 381–388. ISBN 978-0-521-35519-3.

- Lihoreau, Fabrice; Jean-Renaud Boisserie; et al. (2006). "Anthracothere dental anatomy reveals a late Miocene Chado-Libyan bioprovince" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (originally published online May 24, 2006): 8763–7. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.8763L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603126103. PMC 1482652. PMID 16723392.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2009-04-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- [], Chaire de Paléoanthropologie et de Préhistoire, Collège de France, 11 place Marcelin Berthelot, 75005 Paris, France Copyright 2007 The Palaeontological Association

- Allaby, Michael (1999). "Anthracotheriidae". A Dictionary of Zoology. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 15 Apr 2009.

- Douglas Palmer; consultant editor Barry Cox (1999). Palmer, D. (ed.). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-84028-152-1.

- Boisserie, Jean-Renaud; Fabrice Lihoreau; Michel Brunet (February 2005). "The position of Hippopotamidae within Cetartiodactyla". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (5): 1537–1541. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.1537B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409518102. PMC 547867. PMID 15677331.

- Michael Allaby. "Anthracotheriidae." A Dictionary of Zoology. 1999. Encyclopedia.com. 15 Apr. 2009 <http://www.encyclopedia.com>.

- Nature 450, 1190-1194 (20 December 2007) | doi:10.1038/nature06343; Received 26 June 2007; Accepted 3 October 2007

- Pickford, Martin (2008). "The myth of the hippo-like anthracothere: The eternal problem of homology and convergence". Revista Española de Paleontología. 23 (1): 31–90. ISSN 0213-6937.

- Gatesy, J. (1 May 1997). "More DNA support for a Cetacea/Hippopotamidae clade: the blood-clotting protein gene gamma-fibrinogen". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 14 (5): 537–543. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025790. PMID 9159931.

- Ursing, B.M.; U. Arnason (1998). "Analyses of mitochondrial genomes strongly support a hippopotamus-whale clade". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 265 (1412): 2251–5. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0567. PMC 1689531. PMID 9881471.

- Thewissen, JGM; Cooper, Lisa Noelle; Clementz, Mark T; Bajpai, Sunil; Tiwari, BN (20 December 2007). "Whales originated from aquatic artiodactyls in the Eocene epoch of India" (PDF). Nature. 450 (7173): 1190–4. Bibcode:2007Natur.450.1190T. doi:10.1038/nature06343. OCLC 264243832. PMID 18097400. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- Spaulding, M; O'Leary, MA; Gatesy, J (2009). Farke, Andrew Allen (ed.). "Relationships of Cetacea (Artiodactyla) Among Mammals: Increased Taxon Sampling Alters Interpretations of Key Fossils and Character Evolution". PLOS ONE. 4 (9): e7062. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7062S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007062. PMC 2740860. PMID 19774069.