Albanian art

The Albanian art (Albanian pronunciation: [aˈr:ti ʃcipˈta:rɛ] — Albanian: Arti shqiptar) refers to all artistic expressions and artworks in Albania or produced by Albanians. The country's art is either work of arts produced by its people and influenced by its culture and traditions. It has preserved its original elements and traditions despite its long and eventful history around the time when Albania was populated to Illyrians and Ancient Greeks and subsequently conquered by Romans, Byzantines, Venetians and Ottomans.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Albania |

|---|

|

At different times, Illyrian, Ancient Greek and Roman art developed in Albania and survived in a number of media inclusive of architecture, sculpture, pottery, and mosaic. The rock inscriptions in Grama Bay and mosaic in Durrës can be traced back to the 4th century BC and there are nonetheless ancient remains of extraordinary quality available at Apollonia, Byllis, Shkodër, Butrint and elsewhere across the country.

The centerpiece of medieval Albanian art started with the successor of the Roman Empire, namely the Byzantine Empire that ruled the great majority of Albania and the Balkan Peninsula.[1] It comprised gradually of frescoes, murals, and icons painted with an admirable use of color and gold. Onufri, David Selenica, Kostandin Shpataraku and the Zografi Brothers are the most eminent representatives of medieval Albanian art. The Epitaph of Gllavenica, an epitaph written on a shroud, is one of the best artifacts of this genre in the Balkans.

During the Ottoman invasion of Albania, many Albanians migrated out of the area to escape either various socio-political and economic difficulties. Among them, the medieval painters Marco Basaiti and Viktor Karpaçi, sculptor and architect Andrea Nikollë Aleksi and art collector Alessandro Albani.[2][3] Those who resided in the Venetian Empire established the Scuola degli Albanesi that served as a cultural and social center for Albanians.[4]

The Albanian Renaissance, in the field of arts, developed for the first time since the Middle Ages in rather different directions especially toward the occident and was initially dominated by the central figure of Kolë Idromeno. Painters were searching for meaning, traditions and identity, leading initially to realism and later with impressionism.

History

Early period

Within the boundaries of the present Albanian state, there have been several prehistoric Mediterranean cultures that left a number of pictorial records located in the Kryegjata Valley, Goranxi, Maliq, Konispol Cave, Blaz Cave, Gajtan Cave, Treni Cave and numerous other sites throughout Albania.[5][6][7][8][9]

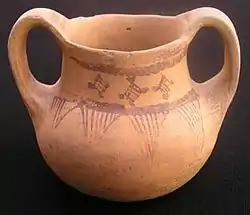

During the Bronze Age, a number of Illyrian and Ancient Greek tribes started to emerge itself on the territory of Albania and established several artistic centers at the same time. Terracotta was widely used by both cultures most notably for reliefs and other architectural purposes. Quite a number of terracotta figures, among others from the Illyrians, were found near Belsh but besides that as well throughout Albania.[10][11][12]

The art of pottery flourished also during that period and is considered amongst the most distinctive art produced from antiquity.[13] Various symbols, rituals, language and folklore were embodied in pottery art. Devollian pottery, named after the Devoll Valley, was made by the Illyrians.[14] Pottery of Illyrians consisted initially of geometric patterns like circles, squares, diamonds and other similar motifs and was nonetheless later influenced by Ancient Greek pottery.[15][16]

From earliest times mosaics have been used to cover floors in principal rooms of buildings, palaces, and tombs, as well as in the formal rooms of private houses. The use of mosaic became widespread in Illyria and Ancient Greek colonies within the Illyrian coast on the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea. The earliest examples of mosaic flooring date to the ancient period are housed in Apollonia, Butrint, Tirana, Lin, and Durrës.[17] The Beauty of Durrës, the earliest mosaic discovered in Albania, is a polychromatic mosaic mainly made of multicolored pebbles.[18] It has a marvelous grace of its figure and great excellence of artistic creativity.

The Roman period is marked by the production of sculptures presented as symbolic art. Roman sculpture was largely influenced by the sculptures of Greece and the Etruscan civilization whereas impressive examples can be mostly found in the cities of Apollonia and Butrint, which flourished during that period.

Medieval Byzantine period

When the Roman Empire was divided in the fourth century, most of Illyria remained in the Eastern Roman Empire that was conventionally known as the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine art, the art of the Eastern Roman Empire from about the 5th century until the fall of Constantinople in 1453, was predominantly marked by religious expressions and a renewed interest in techniques of the Roman Empire mixed with the themes of Christianity.

Icons and frescoes emerged as a significant art form with an extensive church building in Albania. They covered sacred building interior walls, floors and domes increased and expanded in size and importance. The use of gold and bright colors was important indeed each color had its own value and meaning. In addition, colors were never mixed together but were always used pure.

The earliest icons of Albania date from the thirteenth century and generally estimated that their artistic peak reached in the eighteenth century.[1] No paintings before the thirteenth century, produced by Albanians, have been located to date.[1] Nonetheless few older structures in the country house different collections of paintings dating to the Byzantine period.

Manuscripts were another significant feature of Albanian medieval art. The handwritten Codex Beratinus and Codex Beratinus II are two ancient Gospels from Berat, dating from the sixth and ninth centuries. They represent one of the most valuable treasures of the Albanian cultural heritage that was inscribed on the UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in 2005.

By the fifteenth century after the Fall of Constantinople and the invasion of Southeastern Europe by the Ottoman Empire, art produced by Eastern Orthodox Christians living in the Balkans was often named Post-Byzantine art. In that period many valuable monuments and artifacts were made by Albanian painters.[19]

The most famous Albanian painter was Onufri who worked almost his entire life in Albania and Macedonia.[17] Onufri was distinguished for its rich use of colors and decorative shades with certain ethnographic national elements that are more visible with his successors David Selenica, Kostandin Shpataraku and the Zografi Brothers.[17] They lavishly painted diverse churches and monasteries throughout Albania and neighboring countries, especially visible in Berat, Elbasan, Voskopojë, and Korçë.

The Ottoman period of Albania during the fifteenth century is traditionally said to have had a negative impact on Albanian art and so the influences of Renaissance were extinguished. This influence was absorbed and reinterpreted with an extensive construction of mosques that opened a new section in Albanian art, that of Islamic art.[20] This style of art was usually portrayed by the highest degree of motifs, arabesques and ornamentation of interlacing geometrical patterns of polygons, circles and interlocked lines and curves.

Albanian Renaissance

In the nineteenth century, a significant era for Albanian art begins. The great liberation acts starting with League of Prizren in 1878, that led to the Independence in 1912, established the climate for a new artistic movement, which would reflect life and history more realistically and Impressionism and Realism came into dominance.[21]

Kolë Idromeno is perhaps the most famous of the Realist painters in the country and often considered as the introducer of Realism in Albania.[22] Some artists captured the historical past and identity of Albanians in landscapes of vast forests, wide rivers, pristine lakes as well as portraits. Other artists have been focused on social criticism, showing the conditions of the people. By the early twentieth century, a radical artistic change occurred and experienced a patriotic renaissance. The year 1883 is dominated and celebrated for the creation of the most crucial and finest paintings The Portrait of Skanderbeg by Jorgji Panariti and Motra Tone by Kolë Idromeno.

Impressionism did not make itself evident among Albanian artists until after 1900. It did inspired numerous painters among them Vangjush Mio, the first impressionist painter of Albania.

By the middle of the twentieth century, a communist government took rule over Albania and the artwork that arrived during the communist era reflects its time. Art was censored by the government and artists were urged to create works that endorsed socialism. The dominant theme of Albanian paintings was the proletariat, the backbone of the socialist system. Much of the country's art focused on domestic scenes such as men working in the fields and women feeding chickens. Also, landscape scenes were highly popularized by Albanian painters.

Modern period

.jpg.webp)

Although Albania left communism for democracy in 1991, scholars currently label Albanian artwork under the category of "socialist realism", for its emphasis on portraying real people and situations. Although much of Albanian artwork is influenced by impressionism and expressionism, it is most realistic in its depiction of everyday life. Such works can be found at the National Arts Gallery of Albania and the National History Museum both located in Tirana. Contemporary Albanian artwork captures the struggle of everyday Albanians, however, new artists are utilizing different artistic styles to convey this message. Albanian artists continue to move art forward, while their art still remains distinctively Albanian in content.

Alt post-modernism was only introduced fairly recently among Albanian artists, there are a number of artists and works known internationally. Among the most famous Albanian post-modernists are Anri Sala, Sislej Xhafa, Adrian Paci, Oltsen Gripshi, Vénera Kastrati e Helidon Gjergji.

Post-modern tendencies among Albanians were first spotted during the 1980s in Kosovo.[23]

Sculptures of national icons became popular throughout the country. In 1968, Sculptor Odhise Paskali (with help from fellow sculptors Andrea Mana and Janaq Paço) constructed a monument of Skanderbeg, Albania’s national hero, in honor of the 500th anniversary of his death, and it is placed in the center of the capital city of Tirana.

The Tirana Biennale is the main contemporary, international art event. Founded in 2001 by Edi Muka, Gezim Qëndro, and Giancarlo Politi, it has enjoyed over the years the contribution of many international curators, like Francesco Bonami, Adela Demetja, Massimiliano Gioni, Jens Hoffmann, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Harald Szeemann. Many famous Albanian and foreign artists are usually invited.[24]

Dedications

Through different times, various visual art works of foreign artists throughout Europe, such as paintings, portraits, etchings, sculptures, reliefs and works of other genres of art has been dedicated to Albania and the Albanian people.

In 1585, the Italian Renaissance painter, Paolo Veronese dedicated a painting illustrating the Siege of Shkodër from the Middle Ages to the Shkodrans, which is housed on the ceiling of the Doge's Palace in Venice, Italy.[25]

In 1809, the English poet and nobleman Lord Byron arrived in Albania which made a great impression upon him and his life.[26] Afterwards, Thomas Phillips completed in 1813 a portrait of Lord Byron that shows him wearing a traditional Albanian dress that Byron also described it the most magnificent in the world.[27]

Between 1827 and 1828, the French painter, Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps made a visit to Albania that resulted a great series of paintings illustrating the Albanians with their costumes.[28] Among his most impressive and renowned paintings include the Albanian Duel and Les Danseurs Albanais.

Another passionate British painter and poet include Edward Lear who travelled to Albania in 1848 where he was impressively inspired by Albanian landscapes.[29] He lavishly created a grandiose collection of paintings and drawings that depicted the culture, the traditions and lands of the Albanians exactly as it appeared.[17]

Individual works were created even earlier by distinguished authors such as Ary Scheffer (Gratë Suliote), Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (L'Albanaise), Eugène Delacroix (several works), Jean-Leon Gerome (several works), John Singer Sargent (Albanian Olive Pickers), Amedeo Preziosi (Albanians Mercenaries), Erwin Speckter (Portrait of an Albanian women), Charles Bargue (Head of Young man) and William Linton (Albanian Mountains).

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Art of Albania. |

- Architecture of Albania

- Culture of Albania

- Albanian Institute New York

- National Gallery of Figurative Arts of Albania

- List of art galleries in Albania

- List of public art in Albania

Further reading

- Brewer, Bob. My Albania. New York: Lion of Tepelena P, 1992.

- Halliday, Jon. The Artful Albanian. London: Rowland, 1986.

- Pollo, Stefanaq, and Arben Puto. The history of Albania: from its origins to the present day. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981.

- Muka, Edi. Albania Today. The Time of ironic Optimism. Milan, Politi Editore, 1997.

- Schwander-Sievers, Stephanie, and Bernd J. Fischer. Albanian Identities. London: Hurst & Company, 2002.

References

- "Icons from the Orthodox Communities of Albania - COLLECTION OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF MEDIEVAL ART, KORCË" (PDF). helios-eie.ekt.gr. p. 20.

- Walker Art Gallery. Annual Report and Bulletin of the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Andrea Alessi, architect and sculptor, was a native of Durazzo in Albania and possibly of local rather than Italian origin.

- Babinger, Franz (1962). "L'origine albanese del pittore Marco Basaiti (ca. 1470 - ca. 1530)". Atti. Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, Classe di Scienze Morali e Lettere. CXX: 497–500.

- Carol M. Richardson (2007). Locating Renaissance Art. Yale University Press, 2007. p. 19. ISBN 9780300121889.

- Ceka 2013, p. 25.

- Jacques 2009, p. 4.

- Templer 2016, p. 227.

- Jacques 2009, p. 4

- Templer 2016, p. 221.

- Civici, N. (2007). "Analysis of Illyrian terracotta figurines of Aphroditeand other ceramic objects using EDXRF spectrometry†". X-Ray Spectrometry. 36 (2): 1. doi:10.1002/xrs.945.

- John Bagnell Bury; Stanley Arthur Cook; Frank Ezra Adcock (1996). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C.-A.D. 69, 2nd ed., 1996 - Band 10 von The Cambridge Ancient History, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards. University Press, 1996.

- "Bashkia Belsh". qarkuelbasan.gov.al (in Albanian). Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- Aleksandar Stipčević (1977). The Illyrians: history and culture (Aleksandar Stipčević ed.). Noyes Press, 1977. ISBN 9780815550525.

- Irad Malkin (1998-11-30). The Returns of Odysseus: Colonization and Ethnicity. University of California Press, 1998. p. 77. ISBN 9780520920262.

- The Cambridge Ancient History (John Boederman ed.). Cambridge University Press, 1997. 1924. p. 230. ISBN 9780521224963.

- J. M. Coles; A. F. Harding (2014-10-30). Meine Bücher Mein Verlauf Bücher bei Google Play The Bronze Age in Europe: An Introduction to the Prehistory of Europe C.2000-700 B.C. Routledge, 2014. pp. 448–470. ISBN 9781317606000.

- Ferid Hudhri. "2.10. FINE /VISUAL ARTS" (PDF). seda.org.al. p. 2.

- Fjalori Enciklopedik Shqiptar, Akademia e Shkencave - Tiranë, 1984 (MOZAIKU I DURRËSIT ME PORTRETIN E NJE GRUAJE, page 726)

- "KONFERENCA E DYTË E STUDIMEVE ALBANOLOGJIKE" (PDF). albanianorthodox.com (in Albanian). Tirana. p. 2.

- Edmond Manahasa; İlknur Aktug Kolay. "Observations on the existing Ottoman mosques in Albania" (PDF). az.itu.edu.tr.

- MaryLee Knowlton (2005). Albania - Band 23 von Cultures of the world. Marshall Cavendish, 2004. pp. 102–103. ISBN 9780761418528.

- Ferid Hudhri (2003). Albania Through Art. Tirana: Onufri. ISBN 978-9992753675.

- "Shkëlzen Maliqi, Umelec Magazine". Archived from the original on 2008-02-06. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- TICA

- Marin Barleti (2012). The Siege of Shkodra: Albania's Courageous Stand Against Ottoman Conquest, 1478 (David Hosaflook ed.). David Hosaflook, 2012. p. 17. ISBN 9789995687779.

- John Galt (1835). The life of Lord Byron. Harvard University: Harper & Brothers, 1835. pp. 96–100.

- Michael Hüttler; Emily M. N. Kugler; Hans Ernst Weidinger (2015-08-05). Ottoman Empire and European Theatre Vol. III: Images of the Harem in Literature and Theatre. Hollitzer Wissenschaftsverlag, 2015. ISBN 9783990120736.

- Dewey F. Mosby (1977). Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, 1803-1860, Band 1 Outstanding dissertations in the fine arts Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, 1803-1860, Dewey F. Mosby. Garland Pub., 1977. p. 366. ISBN 9780824027148.

- Robert Elsie (2010-03-19). Historical Dictionary of Albania - Band 75 von Historical Dictionaries of Europe (Robert Elsie ed.). Scarecrow Press, 2010. pp. 270–271. ISBN 9780810873803.

.jpg.webp)