32nd Infantry Division (United States)

The United States 32nd Infantry Division was formed from Army National Guard units from Wisconsin and Michigan and fought primarily during World War I and World War II. With roots as the Iron Brigade in the American Civil War, the division's ancestral units came to be referred to as the Iron Jaw Division. During tough combat in France in World War I, it soon acquired from the French the nickname Les Terribles, referring to its fortitude in advancing over terrain others could not.[1] It was the first allied division to pierce the German Hindenburg Line of defense,[1] and the 32nd then adopted its shoulder patch; a line shot through with a red arrow, to signify its tenacity in piercing the enemy line. It then became known as the Red Arrow Division.[2]

| 32nd Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

32nd Infantry Division shoulder sleeve insignia | |

| Active | 1917–1919 1924–1946 1946–1967 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Nickname(s) | "Les Terribles"; "Red Arrow Division" |

| Mascot(s) | Vicksburg |

| Engagements | World War I |

| Decorations | Presidential Unit Citation |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Clovis E. Byers Edwin F. Harding Robert Bruce McCoy |

During World War II, the division was credited with many "firsts". It was the first United States division to deploy as an entire unit overseas and among the first[3] of seven U.S. Army and U.S. Marine units to engage in offensive ground combat operations during 1942. The division was among the first divisions to engage the enemy and were still fighting holdouts after the official Japanese surrender. The 32nd logged a total of 654 days of combat during World War II, more than any other United States Army division.[2][4] The unit was inactivated in 1946 after occupation duty in Japan.

During 1961, the division was called up for a one-year tour of service in the state of Washington during the Berlin Crisis. In 1967, the 32nd Infantry Division (now made up completely of units from Wisconsin) was inactivated and partially reorganized as the 32nd Infantry Brigade, the largest unit of the Wisconsin Army National Guard.

World War I

|

History during World War I

|

Activation, organization and training

When the United States declared war on Germany on 11 April 1917, the Wisconsin Adjutant General ordered the Milwaukee troops to add a squadron, and Troop C and Troop D were added. The Guard units' Troop A and Troop B had been mustered out of federal service less than a year earlier on 20 October 1916 and 6 March 1917, respectively. The Adjutant General then directed the unit to add a new regiment, and the Second and Third Squadrons were formed as the First Wisconsin Cavalry, with units organized in various cities. Troop E commanded by Captain John S. Coney was formed in Kenosha on 10 May 1917, and the Wisconsin Cavalry was officially formed on 29 May 1917.[8]

Only two months later, the 32nd Division was activated in July 1917 at Camp MacArthur, Waco, Texas of National Guard units from Wisconsin and Michigan. Wisconsin furnished approximately 15,000 men, and another 8,000 troops came from Michigan.[9] The division was made up of the 125th and 126th Infantry Regiments (63rd Infantry Brigade) and the 127th and 128th Infantry Regiments (64th Infantry Brigade), as well as three artillery regiments within the 57th Field Artillery Brigade. On 4 August 1917, Battery F, 121st Field Artillery regiment was the first unit to arrive at Camp MacArthur. The remainder arrived as soon as trains could be mustered for transportation.[10]

On 26 August 1917, Major General James Parker assumed command. General Parker had previously been awarded the Medal of Honor during the Philippine–American War. On 18 September 1917, General Parker left for France on special duty with his chief of staff, Lieut. Col. E. H. DeArmond. Brigadier General William G. Haan assumed command in his absence. When General Parker returned in December, he was almost immediately transferred to the 85th Infantry Division at Camp Custer, Michigan. General Haan assumed command once again. In keeping with the 1917 Army Tables of Organizations, he reorganized the division during September to increase the number of men in each regiment.[10]

The 120th Field Artillery Regiment was organized on 22 September 1917 at Camp MacArthur, as a part of the 57th Field Artillery Brigade, better known as the Iron Brigade. The nickname originated with the 1st Wisconsin Cavalry and was traditionally given to crack artillery units in the Civil War.[11] Once at Camp MacArthur, the division was resupplied for their overseas assignment. Shortly before the division left for France, 4,000 National Army troops from Wisconsin and Michigan were transferred to the division.[10]

Captain Alien L. Briggs returned to Camp MacArthur to assist with training. He had been an Aide-de-camp to General Parker and had been in Europe when the war broke out in 1914. He had observed the training methods used in military schools in France. As training intensified in preparation for leaving for France, five French and four British officers, along with several non-commissioned officers, joined the division as instructors. A trench system was built outside the camp in which the division practiced the techniques of trench warfare. There was a continual shortage of equipment that hampered training in the artillery and machine gun battalions. Additional training for junior and non-commissioned officers was implemented, and General Haan offered additional daily instruction to the brigade, regimental and battalion commanders.[10]

By early December, it had received the equipment assigned to it and was judged to be ready for deployment. War Department inspectors found the division more advanced in its training than any other division in the United States. Orders were received in late December, and the first troops left Waco on 2 January 1918 for the New York Port of Embarkation at Hoboken, New Jersey. The infantry was moved first, arriving at Camp Merritt before the division headquarters sailed.[10] The unit received its first casualties when the SS Tuscania (1914) was sunk by a German U-boat. Brigadier General William G. Haan led the unit when it arrived in France.

Combat in France

The 32nd Division arrived on the Western Front in February 1918. The 32nd was the sixth U.S. division to join the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), under General John J. Pershing. The unit's morale was temporarily lessened when they learned they were assigned to create a depot for I Corps that would train replacement soldiers. Major General Haan reminded his commanders that it was every soldier's duty to contribute their best to the war effort, including training replacements. However, Haan lobbied Pershing and after several stormy sessions, finally convinced him that the 32nd could hold its own as a division.[12][13] Up to this point much of the war had been a stalemate, fought from static trench lines over the same few kilometers of terrain. Over the next six months, the division was under constant fire, with only 10 days' rest. The division took a leading role in three important offensives, fighting on five fronts, suffered more than 14,000 casualties, captured more than 2,000 prisoners, and never yielded ground to the enemy.[13]

Major General James Parker had re-assumed command on 7 December 1917, and led the unit into Alsace in May 1918, attacking 19 kilometers (12 mi) in seven days. During the Battle of Marne, they captured Fismes. The only American unit in French General Charles Mangin's famous 10th French Army, it fought between the Moroccans and the Foreign Legion, two of the best divisions in the French army in the Battle of Oise-Battle of Aisne offensive.[9] The 10th Army took Juvigny. In the five-day battle against five German divisions, the 32nd suffered 2,848 casualties.[13]

On 18 May 1918, four battalions of the 32nd division replaced decimated French troops on the front line at Haute Alsace, along a 17 miles (27 km) front from the Aspach-le-Bas to the Swiss border. The division's units conducted combat patrols into Germany itself, gaining the distinction of being the first US troops to set foot on enemy soil in World War I.[12]

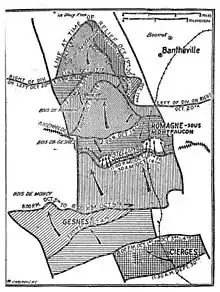

Moving out of their trenches, the division fought continuously for 20 days during the Meuse–Argonne offensive. The division was the front line element of the Third U.S. Army. The Germans were well dug in after four years of trench warfare and had orders to hold the line at all costs. On 14 October at 5:30 am, the division broke through the maze of barbed wire and took the line of trenches forming the Hindenburg Line and moved on to the last German stronghold at Kriemhilde Stellung, where they reached the Meuse River. The 32nd was the first Allied Army unit to penetrate the Hindenburg Line. They then captured Côte Dame de Marie, the key to all the defenses in the area. Over the next five days the division continued to advance while under nearly constant machine gun and artillery fire. The 32nd Division defeated 11 German divisions in the Argonne fighting, including the fearsome Prussian Guards and the German Army's 28th Division, known as Kaiser's Own. The offensive cost the division 5,950 casualties.[9][13]

Their next objective was to flank the Germans at Metz and they marched 300 kilometers (190 mi) to the Rhine River. There they occupied the center sector in the Koblenz bridgehead for four months, during which they held 400 square kilometers (150 sq mi) and 63 towns.[14]

Origin of nickname Les Terribles

The division fought in three major offensives, engaging and defeating 23 German divisions. They took 2,153 prisoners and gained 32 kilometers (20 mi), pushing back every German counterattack.[9] During the drive to capture Fismes, they successfully attacked over open ground at great cost.[1]

The authorized strength of the 3rd battalion was 20 officers and 1,000 men, but by 4 August it had only 12 officers and 350 men on the line. As they advanced over 2,100 yards (1,900 m) of mostly open ground, the Germans targeted them with intense artillery and machine gun fire. They were reinforced by the 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry, which was also understrength. The 127th Infantry finally captured Fismes, but they lost many men. By the end of the day, the 3rd Battalion had only two officers and 94 men; the 2nd Battalion had five officers and 104 men.[1]

General de Mondesir, the 38th French Corps Commander, which the 32nd served under, went to the front to observe the fighting. When he saw how the 32nd cleared the Germans out of their reinforced positions with unrelenting and successful attacks, he exclaimed, Oui, Oui, Les soldats terrible, tres bien, tres bien! General Charles Mangin heard of it and referred to the 32nd Division as Les Terribles when he asked for the division to join his 10th French Army north of Soissons. He later made the nickname official when he incorporated it in his citation for their attack at Juvigny. The division's shoulder patch, a line shot through with a red arrow, symbolizes the fact that the 32nd Division penetrated every German line of defense that it faced during World War I.[1][15][16]

Casualties and decorations

The division was still engaging German troops east of the Meuse River when the Armistice was finally signed. The division suffered a total of 13,261 casualties, including 2,250 men killed in action and 11,011 wounded, placing it third in the number of battle deaths among U.S. Army divisions. The American, French, and Belgian governments decorated more than 800 officers and enlisted men for their gallantry in combat.[9]

All four infantry regiments, the three artillery regiments, and the division's three machine gun battalions all were awarded the Croix de guerre by the Republic of France. The flag and standard of every unit in the division was authorized four American battle streamers.[9] The 32nd Division was the only American division recognized with a nom-de-guerre by an Allied nation during the war.[17]

Inactivation and reorganization

Following the war's end, the division served in the Army of Occupation in Germany, commanded by Maj. Gen. William Lassiter. The division was inactivated on 5 April 1919. On 24 July 1924, the 32nd Division was reorganized incorporating National Guard units from Wisconsin and Michigan. Its headquarters home was at Lansing, Michigan.[9]

World War II

|

History during World War II

|

Pre–World War II

In the period between the World Wars, the 32nd Division was largely a paper unit. During 1937 and 1938, the 107th Engineer Battalion trained at Camp Grayling in Michigan, with emphasis on boat drills and float bridging. The Regiment was short of men, had no vehicles, and what equipment it had was of World War I vintage.[20]

Its training was poor, rarely leaving the local drill hall. Only the fall of France in June 1940 injected some urgency into their training operations, and on 27 August 1940, Congress authorized inducting the National Guard into federal service. Eighteen National Guard divisions were activated, including the 32nd.[21] On 16 September 1940 Congress authorized the first peacetime draft in United States history.[21]

Federalization 1940

When the division was federalized on 15 October 1940, it was made up of National Guard units from Michigan and Wisconsin. It was authorized to have a peacetime strength of about 11,600 soldiers, but like almost all units in the National Guard and the Regular Army prior to World War II, was not at full strength nor was it assigned all of the equipment it was authorized. Training for many soldiers was incomplete.

The division was scheduled to receive a year of training. In October 1940, the division began a six-day motor march to Camp Beauregard, Louisiana. On 26 January 1941, the 32nd Division relocated to the recently completed Camp Livingston, about 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Alexandria, Louisiana.[20] The unit then spent the next 16 months training in Louisiana.[11]

During the summer of 1941, the division moved to Camp Beauregard, Louisiana.[22] as part in the Third and Fourth Army maneuvers—nicknamed the Louisiana Maneuvers—which provided the army high command a good look at the preparedness of the regiment. The first test, which was held in the vicinity of Camp Beauregard, was conducted 16–27 June and included the 32nd Division as well as the 37th Division from Ohio. From 16–30 August, the maneuvers expanded to include the 34th and 38th Divisions. During September, the largest maneuvers were held with the Seventh Corps of the Second Army, opposing the Fourth, Fifth, and Eighth Corps of the Third Army. The Grand Rapids Guard was part of the Fifth Corps. It was the largest maneuver of its kind in the history of the Army and included some 100,000 men.

National Guard units were at the time not required to serve active duty outside of the western hemisphere and draftees were inducted for a maximum of one year of service. But on 7 August 1941, by a margin of a single vote, Congress approved an indefinite extension of service for the Guard, draftees, and Reserve officers, including the Red Arrow Division.[21][23] After the Attack on Pearl Harbor, the division was one of the first activated for federal duty.

During January and February 1942, the division lost one of its infantry regiments when, like all U.S. Army divisions, its "square" infantry division structure was reorganized into a triangular organization, centered on three instead of four infantry regiments. It was left with the 126th Infantry Regiment, 127th Infantry Regiment, and the 128th Infantry Regiment. The three existing artillery regiments (120th, 121st and 126th) were converted into four separate battalions (120th, 121st, 126th and 129th), and supporting units.[22] In early February 1942 it received a new commander, Major General Edwin F. Harding.[22]

Pacific Theater

The division was initially ordered to prepare for an early departure overseas to Europe and the division moved to Fort Devens, Massachusetts, for transport to Northern Ireland.[23] The 107th Engineer Battalion left Camp Livingston on 2 January 1942, and was shipped by train to Fort Dix, New Jersey, where it lost its 2nd battalion and was redesignated the 107th Engineer Combat Battalion. The 107th was shipped ahead of the rest of the division as an advance party so they could prepare an overseas camp for the division's arrival.[24]

The rest of the division was to have three months to prepare for embarkation to the front in Europe. However, Japan had rapidly advanced into the South Pacific, progressively occupying an increasing number of islands. Japan was evidently intent on cutting Australia off from its American supply lines, and Australia feared that Japan was planning to invade. Prime Minister John Curtin demanded the Allies release Australian troops from the Mediterranean and North Africa front to defend their home. The United States initially sent the 41st Infantry Division, less one regiment, from where it was training at Ft. Lewis, Washington. The 41st Division arrived in Melbourne on 6 April 1942.[25]

Though the Allies released the Australian 6th and 7th Divisions, the 9th could not be spared. In a compromise, the 32nd was notified on 25 March, less than six weeks after Harding was placed in command, to turn around and ship out west to the Pacific instead.[26] Harding was told the entire unit was to be ready to board ships in San Francisco in only three weeks. Implementing these orders cost the division's preparedness a great deal.[27] The 35th Division, in lieu of an aborted mission to the Philippines to reinforce American forces there, was designated to replace the 32nd Division for eventual shipment to England.

The 114th Engineer Combat Battalion was hurriedly assigned to replace the 107th Engineers, who were already in the middle of the Atlantic bound for Ireland.[24] On 1 June 1942, the original 107th Engineer Combat Battalion was redesignated the 2nd Battalion, 112th Engineer Regiment; on 19 August 1943, at Saunton Sands near Camp Braunton, England, the 2nd Battalion, 112th Engineers was redesignated as the 254th Engineer Combat Battalion.[28]

The division boarded 13 freight trains and 25 passenger trains at Fort Devens near Boston on 9 April 1942 and arrived five days later in Oakland, California. Portions of the unit were then transported by bus to Pier 7 in San Francisco, where they boarded the U.S. Army ferry USAT General Frank M. Coxe for Angel Island in San Francisco Bay, which was utilized by the Army as Fort McDowell.[29][30] :33 The remainder were housed at Fort Ord near Monterey, California, at the Dog Track Pavilion in Emeryville and at the Cow Palace, where the men slept uncomfortably in stadium chairs and in horse stalls.[30]:38

On 22 April 1942, just before the division boarded ships in San Francisco bound for Australia, they received about 3,000 additional soldiers, most of whom had just finished basic training, to fill in their incomplete ranks. The division was still missing about 1,800 men. The division had to make do with whatever equipment was found in depots near San Francisco. Not even its firearms allocation was complete; it could not obtain any compact M1 carbine rifles meant for officers and support forces, forcing the division to arm them with the regular infantry's longer, heavier yet more powerful M1 Garand.[27][29] They traded in their World War I-era horse-drawn artillery pieces for new 105mm M101 howitzers, though they received scant training on the new guns.

After eight days waiting for transit, the division returned to San Francisco and boarded a convoy of seven Matson Line ships, including the S.S. Lurline and USS Hugh L. Scott at Pier 42. The convoy (SF 43) was escorted by the cruiser USS Indianapolis and two corvettes. Four days out of San Francisco, the Lurline ship's crew discovered the division's mascot, a dog named Vicksburg. She was named for the town she was born in and the location of the final major campaign of the American Civil War. (Vicksburg was killed in a road accident in Southport, Australia on 8 October 1942).[31] A monument to the dog still exists at the former entrance to Camp Cable.[32][33]

Taking a southerly route to avoid the Japanese Navy, they arrived in southern Australia at Port Adelaide on 14 May 1942, having traveled 9,000 miles (14,000 km) in 23 days.[29] They were the first American division in World War II to be moved in a single convoy from the United States to the front lines.[30]:38

Training in Australia

After the division arrived in Adelaide, the 126th Infantry Regiment was sent to Camp Sandy Creek (north of Adelaide), and the 127th and 128th went to Camp Woodside, east of Adelaide and 30 miles (48 km) from Camp Sandy Creek.[30]:41 Once the unit arrived in Australia, rather than begin combat training, the division was forced to build its new camps from scratch. Their initial training was planned to be oriented around a defense of the Australian mainland. However, instead of learning the basics of patrolling and maneuvering, they cut down trees, dug wells and latrines, and set up kitchens and tents.[34] The division did not begin training again for several weeks.[30]:50–51

Preparedness for jungle warfare

Although the 32nd had spent a good deal of time training in Louisiana with considerable swamp close at hand, their destination at that time was Europe. Most official records state that the men had little additional training for jungle conditions while in Australia. General Eichelberger, MacArthur's Chief of Staff, wrote that "In Washington I had read General MacArthur's estimates of his two infantry divisions, and these reports and our own inspections had convinced my staff and me that the American troops were in no sense ready for jungle warfare." However, some veterans interviewed report they received general training with weapons and practice at terrain maneuvers, and in jungle warfare. They said this increased once the unit arrived in Brisbane.[23]

Less than two months after their arrival in Australia, the unit was moved in July 1942 halfway across Australia, 1,223 miles (1,968 km) northeast to Camp Tamborine, about 50 kilometers (31 mi) south of Brisbane on Australia's east coast. The majority of the division and its equipment was split up and shipped by railroad, while some were transported on five Liberty Ships. Each Australian state had a different rail gauge (or width), and the equipment and men had to be offloaded at each state's boundary and reloaded onto a new train. The division's trains crossed four states before it reached Brisbane.[24]

On 30 August, Camp Tamborine was renamed Camp Cable, in honor of Sergeant Gerald O. Cable, a soldier in Service Company, 126th Infantry. Sergeant Cable was the sole casualty when his Liberty ship, en route from Adelaide to Brisbane, was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, making him the first soldier of the 32nd Division to die in combat during World War II.[35]

Japanese assault on Port Moresby

The Battle of Coral Sea in early May followed by the Allied victory at the Battle of Midway in early June foiled Japan's plans to capture Port Moresby by sea. The Japanese were undaunted. A Japanese convoy conveyed Maj. Gen. Tomitarō Horii with about 4,400 troops onto the beach at Gona during the night of 21–22 July 1942 on the north-eastern shore of Papua New Guinea. They proceeded inland to Popondetta and then south-westward onto the Kokoda Trail with the object of capturing Port Moresby. By 13 August, the Japanese had landed about 11,100 men, which the object of securing a base to dominate the south Pacific. The Allies commonly believed the Japanese intended to invade Australia, whose Cape York Peninsula was only 340 miles (550 km) from New Guinea. Unknown to the Allies, the Chief of the Imperial Japanese Naval General Staff, Osami Nagano, had proposed an invasion, but this plan was rejected in favor of a decision to occupy Midway Island with the intention of cutting Australia off from United States supply lines, eventually forcing Australia to surrender.

General Willoughby continued to believe that the Japanese only intended to build airfields on the northern coast with the intent to attack Port Moresby and Australia by air. But the Japanese fought up the northern side of the Owen Stanley Mountains and in the middle of September, after weeks of fighting, descended the southern slopes to Ioribaiwa Ridge, within 32 kilometers (20 mi) of Port Moresby. At the peak of their effort, the Japanese had 16,000 troops in the region.[36] Japanese engineers remained on the coast to fortify the beachhead and build a system of reinforced and cross-linked bunkers.[30]:48

The Allied air forces relentlessly attacked the Japanese supply lines over the Owen Stanley Mountains that connected the Japanese forces to Buna, Sanananda, and Gona. The weakened Japanese forces, attacked from the air and on the front and flanks by Australian forces, were finally stopped on 17 September at Imita Range, south of Ioribaiwa.[37]:214–215

Japanese withdrawal from Kokoda Track

On Guadalcanal, Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake's initial thrust to re-take the island's Henderson Field had been badly defeated. Meanwhile, a landing at Milne Bay had also been repulsed.[37]:230 With the concurrence of the Japanese command staff, he ordered General Horii to withdraw his troops on the Kokoda Track until the issue at Guadalcanal was decided.[38]:162–193 On 28 September, General Horii and his troops began to hastily withdraw northward over the Owen Stanley Mountains to Kokoda and then to Buna–Gona.[39]

Transport to New Guinea

General Douglas MacArthur had repeatedly requested Washington, D.C. to send him additional troops with which to initiate an offensive campaign and had been pointedly told he would have to make do with the troops on hand.[25] MacArthur had decided as soon as he had reached Australia that the key to its defense lay not on the mainland but in New Guinea.[25] On 13 September 1942 he ordered parts of the 32nd Division to Papua New Guinea even though they had less than two months of training. This would become part of the opening ground offensive against Japanese troops in the Southwest Pacific Area, and MacArthur expected the Americans to quickly and easily advance on and capture the Japanese forward base at Buna.[40]

The U.S. Army typically required divisions to train as a unit for a full year before entering combat.[41] The 32nd had arrived in Australia in April 1942, spent several weeks building its first camp, was transported to a new camp in July, and nearly one third of its troops had been in boot camp only five months previously. Nonetheless U.S. officers decided it was the most combat-ready unit in Australia.

Kapa Kapa Trail march

The Australian Army units on New Guinea were under increasing pressure from the Japanese forces who had advanced within 32 kilometers (20 mi) of Port Moresby. Anxious to blunt the Japanese attack, and although no white man had crossed using that route since 1917, General Douglas MacArthur issued orders for United States forces to take the Kapa Kapa Trail running parallel to the Kokoda Track. The 32nd's Divisional Headquarters and two regimental combat teams formed around the 126th and 128th infantry regiments were deployed to Port Moresby between 15 and 29 September 1942.[27]

MacArthur believed based on available intelligence that the U.S. forces could guard the right flank of the Australian forces and entrap the Imperial Japanese troops between the two allied forces.[42] Beginning on 14 October 900 troops of the 2nd Battalion, 114th Engineer Battalion, 19th Portable Hospital, and the 107th Quartermaster Company of 126th Infantry, commanded by Lt. Col. Henry A. Geerds, departed in stages from Karekodobu, nicknamed "Kalamazoo" by the GIs who had a hard time pronouncing the local name.

They were charged with making an extremely difficult trek inland over the Kapa Kapa Trail toward Jaure, where they were to flank the Japanese on the Kokoda Trail. The total distance over the mountains to the Japanese positions was over 130 miles (210 km), and most of the trail was barely a goat path.[43] The men carried only six days rations, expecting to be resupplied en route. The food, however, was very poor, including hardtack, rice and bully beef, some of which had become rancid and sickening many men.[44]:108 They had leather toilet seats[45] but no machetes, insect repellent, waterproof containers for medicine or personal effects, and it rained heavily every day.[46] The men found themselves utterly unprepared for the extremely harsh conditions found in the jungle. The Kapa Kapa trail across the Owen Stanley divide was a "dank and eerie place, rougher and more precipitous"[43] than the Kokoda Track on which the Australians and Japanese were then fighting.

Lead elements of the 126th finally crossed the 2,800-meter (9,200 ft) gap near Mount Obree, which they nicknamed Ghost Mountain, where all of the remaining native porters abandoned the Americans, leaving them to carry their own equipment. On 20 November 1942, after almost 42 days on the trail, crossing exceedingly difficult terrain, including hogback ridges, jungle, and mountainous high-altitude passes, E Company was the first to reach Soputa near the front. The remainder of the battalion trickled in over the next few days.[44]:109 As a result of the extremely difficult march and the decimated ranks of the unit, the battalion earned the nickname of The Ghost Battalion.[30]:378 No other troops were tasked with making the same trek.

Attack on Buna

Two weeks later the remainder of 128th RCT was flown to Wanigela near the Buna where they joined the Australian 18th Brigade. They were to begin an assault on 16 November 1942 on the main Japanese beachheads in eastern New Guinea.

The 32nd Division was among the first of all US divisions to engage in a ground assault against the enemy in World War II.[3] General Harding was nearly killed before the attack began. The first day of the assault, Harding was on board a sixty-two-foot wooden coastal trawler, the Australian civilian crewed Minnamurra that was operating as part of the U.S. Army's Small Ships Section, with his headquarters company when it and its convoy carrying important artillery and supplies was attacked by Japanese fighter-bombers.[47] Harding saved himself by diving overboard and swimming to shore. The attack destroyed all five vessels and the supplies Harding was relying on for the upcoming attack.[48] More were sunk over the following days or ran aground. General George Kenney wielded a great deal of influence over MacArthur, and although he had no knowledge of jungle warfare, insisted that tanks had no role in ground action in the jungle, but that the "artillery in this theater flies."[49] Harding reluctantly accepted MacArthur's decision to go ahead with the attack and to rely on direct air support in place of tanks or heavy artillery.

Japanese defenses

The Japanese were now commanded by Maj. Gen. Kensaku Oda, who succeeded General Horii, who had drowned in the Kumusi River[37]:248 while retreating from their initial attack across the Kokoda Track on Port Moresby. The Japanese at Buna-Gona were unable to dig deep trenches or shelters due to the 91-centimetre-deep (3 ft) water table. Instead, they built hundreds of coconut log bunkers.[37]:246 These had mutually supporting lines of fire and were organized in depth. The bunkers were often linked by trenches allowing the Japanese to move at will among them, reinforcing one another.[44]

Buna was General Douglas MacArthur's first ground offensive campaign against Japanese troops in World War II. He received intelligence from Brigadier General Charles Willoughby, who told MacArthur before the operation that there was "little indication of an attempt to make a strong stand against the Allied advance."[40] Other intelligence he received led him to believe that Buna was held by about 1,000 sick and malnourished soldiers. Unfamiliar with the state of Japanese defenses, Lieutenant General Richard K. Sutherland, MacArthur's chief of staff, glibly referred to these fortifications as "hasty field entrenchments."

The division's performance in battle under the circumstances was not surprising. It was unprepared for offensive operations against what turned out to be some of the strongest Japanese fortified positions in the South Pacific, and was severely hampered by completely inadequate fire support.[27]

Harding relieved

After taking a large number of casualties and making virtually no progress, MacArthur became frustrated with the 32nd Division's performance and gave Major General Robert Eichelberger authority to remove Harding, which Eichelberger promptly did. Eichelberger then ordered a two-day pause in operations, had hot food brought to the front, got additional supplies moved forward, and was able to get the detached 128th restored to the division. These were all actions that Harding had requested and been denied.

Casualties and refitting

U. S. Air Force historian Stanley Falk wrote, "The Papuan campaign was one of the costliest Allied victories of the Pacific war in terms of casualties per troops committed."[30] Of the 9,825 men of the 32nd Division who entered combat, the division suffered 2,520 battle casualties, including 586 killed in action. More telling was the huge number who were casualties due to illness: 7,125 (66%, with 2,952 requiring hospitalization), and 100 more died from other causes. The total casualty count of 9,956 exceeded the division's entire battle strength.[27][50]

The Ghost Mountain Boys of the 2/126th were especially hard hit. When Buna was taken they finished the fight with only six officers and 126 troops standing out of the 900 plus who had started out from Kapa Kapa.[51] The extremely difficult 210-kilometer-long (130 mi) march by the U.S. 2/126th from Kapa Kapa to Jaure and the brutal combat at Buna-Gona taught the Allied armies important lessons that they applied throughout the Pacific Theater and remainder of the war in the Pacific.[52]

Refitting and retraining

After the 32nd Division wrapped up operations at Buna, the men were slowly transported to Australia for rest, rehabilitation and training. The first units arrived in Brisbane, Australia on 1 March 1943. The complete move took several weeks because of the limited number of planes available to transport the troops over the Owen Stanley Mountains and the few ships available to get the men from Port Moresby to Australia. The last units arrived in April.[53] Upon arrival, some men spent a few days camped near Brisbane and went into town to get drunk. The division then returned to Camp Cable where it had been stationed before it left for New Guinea.[53]

On 1 March 1943, Major General William H. Gill at Camp Carson, Colorado was ordered to Australia to assume command of the division. After a period of rest, the division began training to incorporate the many replacements into its ranks and help them gain the lessons of jungle warfare they had gained in battle. During March, the 107th Quartermaster Battalion was reorganized as the 32nd Quartermaster Company, and the ordnance detachment was redesignated the 732nd Ordnance Company. The 121st Field Artillery Battalion's 155 mm howitzers were replaced with 75 mm howitzers. By October 1943 the division was ready for combat and moved back to New Guinea.[53] From 16 to 30 October 1943 the 32nd Division was moved from Australia back to New Guinea. At Milne Bay and Goodenough Island they continued their training and prepared for future combat operations.[53]

During December 1943 the U.S. Sixth Army was given the mission to capture Saidor with the goal to cut off the Japanese retreat from Finschhafen. The 32nd division formed the majority of the Michaelmas Task Force given the assignment to help establish a blocking position at Saidor with the intent to trap an entire Japanese division at Sio. They were charged with seizing the airfield at Saidor and securing the surrounding area. The main combat power for the task force was the 126th Infantry.[53]

Operation Cartwheel and Western New Guinea

On 2 January 1944, the 32nd Division took part in Operation Cartwheel, part of MacArthur's "leap-frog" operational plan to take strategic points to use as forward bases. MacArthur sent Allied forces westward along the 1,500 miles (2,400 km) northern coast of New Guinea in a sequence of operations against selected locations that would provide landing fields for aircraft. This was designed to provide his ground forces with continued close air support and deny the enemy sea and airborne resupply, effectively cutting the Japanese forces off as they were under attack.[54][55]

Elements of the 32nd's 126th Infantry Regimental Combat Team landed at Saidor on the north coast of New Guinea and helped to end enemy resistance there on 14 April 1944.[56] On 23 April, elements took part in the landing at Aitape, the division arriving on 3 May. After meeting slight initial resistance, the 32nd had to withstand savage counterattacks in the Driniumor River area.[57]

By 31 August, Aitape was secured and the division rested. Elements landed on Morotai on 15 September. The 32nd's command post opened at Hollandia, Dutch New Guinea on 1 October, setting the stage for the advance into the Philippines.

Battle of Leyte

The Battle of Leyte was the invasion and conquest of Leyte in the Philippines by American and Filipino guerrilla forces under the command of MacArthur. The U.S. forces fought Japanese Army forces led by General Tomoyuki Yamashita. The battle took place from 17 October to 31 December 1944 and launched the Philippines campaign of 1944–45, the goal of which was to recapture and liberate the entire Philippine Archipelago and to end almost three years of Japanese occupation. The 32nd was in reserve and was not deployed to Leyte until 14 November when it was assigned to the US X Corps. It relieved the 24th Infantry Division and went into action along the Pinamopoan-Ormoc highway, taking Limon and smashing the Yamashita line in bitter hand-to-hand combat. The division linked up with elements of the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division in the vicinity of Lonoy, on 22 December, marking the collapse of Japanese resistance in the upper Oromoc Valley. The division remained on the front lines until the Japanese resistance on Leyte was broken near the end of December.[58]

Battle of Luzon

From Leyte the division moved to Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, on 27 January 1945. It pushed up the Villa Verde Trail, on 30 January, and after 119 days of fighting, it took Imugan.[59] Four men were awarded the Medal of Honor during its six-week fight up the 20 miles of the Villa Verde Trail: William R. Shockley, David M. Gonzales, Thomas E. Atkins, and Ysmael R. Villegas. It took American troops until the end of June to seize the Cagayan Valley and its food supplies.

On 28 May it met the 25th Infantry Division near Santa Fe, securing Balete Pass, the gateway to the Cagayan Valley. While elements of the division continued mopping-up activities near Imugan, other units moved to rest and rehabilitation centers. Active elements secured the Baguio area, wiped out Japanese forces in the Agno River Valley area, and opened Highway 11 as a supply route. They captured General Tomoyuki Yamashita, who surrendered on 2 September 1945, in Kiangan. "It was a great moment for the 32nd," wrote Maj. Gen. William H. Gill, commanding general of the Red Arrow Division, "a glorious finish to this long bitter struggle."[59]

End of the war

Operations officially ceased on 15 August 1945 when Japan surrendered, although A Company beat off a banzai charge during the morning that killed one soldier and wounded two others, and another 18 hours later in which another soldier died and seven were wounded.[60]

On 9 October, the 32nd Division left Luzon for Japan and occupation duty in a convoy of 31 ships. They arrived on 14 October at Sasebo, Japan on the island of Kyushu. The 32nd stayed in Kyushu until the division was inactivated on 28 February 1946.[22] Among the first to enter combat,[3] and the very last to cease fighting, the 32nd was in combat for 654 days, more than any other United States Army unit during World War II, and eleven of its men were awarded the Medal of Honor.[61][62] It was estimated the division had killed over 32,000 Japanese soldiers during the war.[60][63]

Many firsts

The 32nd Division was the first division to deploy as an entire unit from the United States and the first division to be shipped as a single convoy overseas. Once in the South West Pacific Area, portions of the 128th Infantry were the first to be airlifted into combat, from Australia to Port Moresby, New Guinea.[19]

United States forces first launched amphibious offensive operations against the Japanese during the summer and fall of 1942. These were led by the 1st Marine and the Americal divisions on Guadalcanal beginning on 7 August, followed by Carlson's Raiders on Makin Island on 17 August.[64]

On 16 November the 32nd became the first U.S. forces to launch a ground assault against Japanese forces.[3][19] They were followed by the 163rd Regimental Combat Team of the 41st Infantry Division, which arrived at Port Moresby, New Guinea on 27 December, and whose first elements flew over the Owen Stanley Range to the Buna Gona front on 30 December.[65]:329–330 On the Atlantic front, the first units to engage in a ground assault were the 1st Infantry, 3rd Infantry, 9th Infantry, 1st Armored and the 2nd Armored Divisions in North Africa on 8 November.[66]

In another first, the four gun sections of Battery A of the 129th Field Artillery became the first howitzers flown into a war, first carried to Port Moresby by a B-17 bomber. Then one half of Battery A, 129th Field Artillery, a single 105 mm howitzer, was air-lifted in pieces by three Douglas Dakota aircraft over the Owen Stanley Range to Buna, becoming the first U.S. Army artillery flown into combat in World War II.[19]

At Saidor, they became the first U.S. division to make a beach landing in the New Guinea campaign. They were the first to employ General MacArthur's "by-pass strategy," leaving some Japanese units alone and attacking behind them to cut them off from their lines of supply. In the battle for Aitape, they were the first division to simultaneously supply 11 battalions in combat in one action completely by airdrop. Later on, in the Battle of Leyte, they were the first to supply four infantry battalions for two days from artillery liaison "Cub" planes. They were the first to publish an American servicemen's letterpress newspaper (the Stalker)[67] in the Southwest Pacific. Finally, elements of the 32nd Division were among the first American occupation troops to land in Japan.[19]

Division march

Theodore Steinmetz wrote and conducted the words to a march song about the unit's origins and tenacity.[68]

Look out! Look out!

Here comes the Thirty Second

The mighty Thirty Second

The fighting Thirty Second

Look out! Look out!

They led the way in France

Red Arrows never glance

Though hell burn in advance

Yea! On Wisconsin On Wisconsin

Michigan My Michigan

We fight for liberty

For justice and equality

Post-war criticism

In 1949, U.S. Air Force General George Kenney published General Kenney Reports, a personal history of the air war he commanded from 1942 to 1945. In it he praised Australian Generals George Vasey and George Wootten, commanders of the 7th and 9th Divisions, but he also criticized Australian Lieutenant General Sydney Rowell, who was dismissed by General Edmund Herring for insubordination.[69]:219 He said Rowell had a "defeatist attitude." Of the U.S. 32nd Division, he said the troops "were green and the officers were not controlling them." He quoted General Herring and Major General Sir Thomas Blamey as critical of the 32nd's efforts. Kenney said the 32nd sat in the jungle for 10 days "doing nothing but worrying about the rain and the strange noises at night."[70]

In a letter to General Herring in 1959, General Eichelberger responded to criticism about Herring's dismissal of General Rowell and his dismissal of General Harding:

It is a funny thing about war historians. If a general dismisses a subordinate at any time he is immediately attacked; whereas in our football game, if you have a better player for a particular place, you always play him, and everybody expects you to do this. I have little doubt that the same is true of your ball game. War historians never seem to give generals credit for having thought that X might be better than Y for the next phase of operations.[71]

Decorations and citations

At the conclusion of the Buna Campaign in April 1943, the division was sent to Australia for recuperation, replacement, and re-training. On 6 May 1943, the 32nd Division was awarded the Distinguished Unit Citation, a streamer embroidered Papua, for "outstanding performance of duty in action during the period 23 July 1942 to 23 January 1943." The citation read:

When [a] bold and aggressive enemy invaded Papua in strength, the combined action of ground and air units of these forces, in association with Allied units, checked the hostile advance, drove the enemy back to the seacoast and in a series of actions against a highly organized defensive zone, utterly destroyed him. Ground combat forces, operating over roadless jungle-covered mountains and swamps, demonstrated their courage and resourcefulness in closing with an enemy who took every advantage of the nearly impassable terrain. Air forces, by repeatedly attacking the enemy ground forces and installations, by destroying his convoys attempting reinforcement and supply, and by transporting ground forces and supplies to areas for which land routes were non-existent and sea routes slow and hazardous, made possible the success of the ground operations. Service units, operating far forward of their normal positions and at times in advance of ground combat elements, built landing fields in the jungle, established and operated supply points, and provided for the hospitalization and evacuation of the wounded and sick. The courage, spirit, and devotion to duty of all elements of the command made possible the complete victory attained.[72]

It was also recognized by the Philippine government for its efforts in the battles for Leyte and Luzon with the Philippine Presidential Unit Citation, the streamer embroidered, "17 OCTOBER 1944 TO 4 JULY 1945".

Recent history

The division was recreated within the Army National Guard after the end of the Second World War in 1946. In 1954, it comprised the 127th, 128th, and 426th Infantry Regiments, 120th, 121st, 126th, and 129th Field Artillery Battalions, 132nd Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion, 132nd Tank Battalion, and other units, including the 724th Engineer Battalion.[73]

On 6 September 1961, with the heightening of the tensions due to the Berlin Crisis, the 32nd Infantry Division was alerted to an impending call-up. The commanding general, Major General Herbert A. Smith was notified a few days later that the division was to report on 15 October 1961 to Fort Lewis, Washington, for active duty. This was exactly 21 years after their activation date for World War II, at which time then Lt. Col. Herbert A. Smith had been commander of the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry. The unit served until August 1962 at Fort Lewis, Washington, and was assigned to the Strategic Army Command. The division began training as replacements for the 4th Infantry and the 2nd Armored Divisions at Fort Lewis, Washington, and Fort Hood, Texas, in case they were deployed overseas as reinforcements for the Seventh Army in Germany. They returned to Wisconsin without being deployed overseas.[76]

The 32nd Division (as were all U.S. infantry divisions at the time) was organized in a Pentomic division, composed of five line (rifle) companies, a combat support company, and a headquarters company. From 1940 until 1959, divisions had contained three regiments. This divisional structure was found unwieldy and was eliminated in 1963.

Reorganized as brigade combat team

In 1967, the 32nd Division—by then made up entirely of Wisconsin units—was inactivated and reorganized as the non-divisional 32nd Separate Infantry Brigade. In 1971, the brigade was converted to mechanized infantry. In 1997, the 32nd reorganized from a separate to a divisional brigade, reducing in the process the staff of its headquarters from 300 down to 85.

After it was converted back to light infantry, Army officials designated the 32nd an "enhanced" brigade, eligible for a higher level of funding and other resources than most National Guard brigades receive. Changing the brigade's shape to fit the profile of a light brigade also meant significant benefits for the unit and for the state, including more than US$6 million a year in additional federal funds to operate units and provide training and logistics support. This also meant an increase in the number of physical assets, such as trucks and scoop loaders, which are available to the state in an emergency.

Major changes in the structure of the 32nd Infantry Brigade included:

- One new infantry battalion—the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry—was formed to fill the brigade's three-battalion infantry complement.

- The 173rd Engineer Battalion and the 1st Battalion, 632nd Armor, were deactivated. Similar or related missions were assigned to new, smaller units—the 32nd Engineer Company and Troop E, 105th Cavalry, a light reconnaissance unit.

- The 1st Battalion, 120th Field Artillery converted from the 55,000-pound (25,000 kg) 155 mm self-propelled howitzer to the more easily transported 4,475-pound (2,030 kg) 105 mm towed howitzer.

- The brigade added an intelligence unit, the 232nd Military Intelligence Company.

- New detachments were formed in the 132nd Support Battalion to provide transportation support to the brigade's three infantry battalions.

The 32nd Brigade headquarters moved from Madison to Camp Douglas and Wausau, locations more central to the brigade's statewide units.

The changing mission of the 32nd Separate Infantry Brigade (Mech.) from mechanized to light infantry also brought many changes for the Maneuver Area Training Equipment Site (MATES) at Fort McCoy. The 32nd is part of the Wisconsin Army National Guard. MATES is owned and operated by the State of Wisconsin and the Wisconsin Army Guard so it is tasked to support the 32nd's equipment needs. MATES was required to bring 32nd equipment not necessary for light infantry, such as M1 tanks and the M113 armored personnel carriers (APCs), up to Army standards so they can be re-distributed to other units.

In February 2009, the 32nd Brigade deployed 3,200 members on a fourteen-month deployment to Iraq, its largest deployment since World War II.[77]

Legacy

Several people who served in the division gained notability during and after their time in the division. In World War I, PFC Joseph William Guyton (1889–1918), became the first American killed on German-held territory, earning him the French Croix de guerre. During World War II, notable members of the division included Captain Herman Bottcher, recipient of two Distinguished Service Cross Medals, Captain William "Bill" Walter Kouts, and Private John Rawls, recipient of a Bronze Star who later became a political philosopher.

Additionally, eleven men were awarded the Medal of Honor while serving with the division, all for action during World War II. They include PFC Thomas E. Atkins, Private Donald R. Lobaugh, PFC David M. Gonzales, Staff Sergeant Ysmael R. Villegas, PFC Dirk J. Vlug, Staff Sergeant Gerald L. Endl, Sergeant Kenneth E. Gruennert, First Sergeant Elmer J. Burr, Sergeant Leroy Johnson, PFC William A. McWhorter, and PFC William R. Shockley.

For its efforts in both World Wars, the division has been honored and memorialized by communities throughout the United States and Philippines for its actions. Some of these memorials include:

- The 32nd Division March song, written by Theodore Steinmetz, is still played by marching bands to this day.[68]

- Wisconsin Highway 32 (WIS 32), as well as a portion of former U.S. Route 12 in Michigan (now Red Arrow Highway), are named in honor of the 32nd Infantry Division, and all WIS 32 markers carry the Red Arrow insignia.[78] A memorial plaque describing the division is located at southern end of WIS 32 on Sheridan Road in Kenosha County, Wisconsin.[79] Ceremonies were held along the route and included veterans of the Grand Rapids Guard, which had been part of the Thirty-second Division during both world wars.

- Lowell High School in Lowell, Michigan, adopted the nickname Red Arrows in honor of the 32nd Infantry Division shortly after their return.

- A memorial to the division was built in San Nicolas, Pangasinan, Philippines. It is inscribed, "Erected by the officers and men of the 32d Infantry Division United States Army in memory of their gallant comrades who were killed along the Villa Verde Trail 30 January 1945 – 28 May 1945".

- The Red Arrow Elementary School in Hartford, Michigan, is named for the division

- The Red Arrow High School in San Nicolas, Pangasinan, Philippines was named in honor of the division

- Milwaukee built the Red Arrow Park dedicated to the men of the 32nd Red Arrow Division who came from Wisconsin following World War I. When Interstate 43 was built over the site, the park was relocated to a site just north of Milwaukee City Hall at E. State Street and N. Water Street. On 11 November 1984, the city dedicated a red granite monument at the park. At its base is inscribed "Les Terribles".

- Red Arrow Park in Kenosha, Wisconsin is dedicated to the division.[80]

- Red Arrow Park in Manitowoc, Wisconsin is dedicated to the division.[81]

- Red Arrow Park in Marinette, Wisconsin, is dedicated to the division.

- A memorial to the division was built in Arcadia, Wisconsin. It bears the inscription:

The 32nd Red Arrow Division was first formed in July 1917 at Camp McArthur, Waco, Texas of National Guard units from both Wisconsin and Michigan. Its 27,000 men arrived in Europe in January and February 1918. It was the first division to pierce the famed German Hindenburg line of defense. From a French general, then all French troops, it was given the fearsome name "Les Terribles." This is the division whose shoulder patch is the Red Arrow, shot through a line denoting that it pierced every battle line it ever faced. The 32nd division was inactivated and retired in 1967.

- Veterans of Foreign Wars Post #1527 "The Red Arrow Post" in Portage, Michigan is named in their honor.

Notable former members

- Byron Darnton, World War I

References

Citations

- "The 32nd Division in World War I: From the "Iron Jaw Division" to "Les Terribles"". The 32nd 'Red Arrow' Veteran Association. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- Hubbuch, Chris (11 November 2008). "Remembering Wisconsin's citizen soldiers". La Crosse Tribune. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- "Michigan National Guard in World War II". State of Michigan. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- "Wisconsin National Guard Museum". Wisconsin Veterans Museum Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- "Division History: 32nd Infantry Division". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "Organization of the 32D Division during WWI - 32D 'Red Arrow' Veteran Association". www.32nd-division.org. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- "The History of the 32d Division National Guard". Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- "1st Battalion, 126th Field Artillery". 23 May 2005. Archived from the original on 15 November 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- Department of Military and Veteran's Affairs. "World War I". Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- "Birth of the Thirty-Second Division". Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- "1st Battalion – 120th Field Artillery Regiment". Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- "Marshall Beattie and the Red Arrow Division". Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- Nolan, Jenny (13 September 1997). "The Red Arrow Division: Fierce fighters of the first World War". The Detroit News. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- File:The 32nd Division in the World War, 1917-1919 (IA 32nddivisioninwo00wisc).pdf

- "32nd Infantry Division". The National Guard Education Foundation. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- 32nd-Division.org History of the Red Arrow Insignia Archived 13 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Brief History of the "Red Arrow" From the 32nd Division to the 32nd Infantry Brigade". The 32nd 'Red Arrow' Veteran Association. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths (Statistical and Accounting Branch, Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- "Highlights of the 32nd Infantry Division "The Red Arrow" in World War II". The 32nd 'Red Arrow' Veteran Association. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- Frederick Stonehouse. "Combat Engineer! The History of the 107th Engineer Battalion (1881–1981)". Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- Anderson, Rich. "US Army in World War II Introduction and Organization". Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- "Remembering the war in New Guinea: 32nd U.S. (Red Arrow) Infantry Division". Archived from the original on 16 September 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- Brockschmidt, Kelli. "The New Guinea Campaign: A New Perspective Through the Use of Oral Histories". McNair Scholars Journal. Grand Valley State University. 9 (1). Archived from the original on 28 December 2013.

- "The 32nd Infantry Division "The Red Arrow" in World War II". Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- Samuel Milner (December 2002). Victory in Papua. United States Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 978-1-4102-0386-1. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- "The Kokoda Track: Ghost to Coast". Archived from the original on 15 September 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- Fenton, Damien (12 September 2003). "32nd US (Red Arrow) Infantry Division (Overview text)". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- "History of the 254Combat Engineers in World War II". Archived from the original on 22 April 2001. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Bagley, Joseph. "My father's wartime experiences: Francis G. Bagley, Company B, 114th Combat Engineers, 32nd US Infantry Division". Remembering the war in New Guinea. Archived from the original on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- Campbell, James (30 September 2008). The Ghost Mountain Boys: Their Epic March and the Terrifying Battle for New Guinea—The Forgotten War of the South Pacific. Three Rivers Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-307-33597-5. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018.

- "Suburban histories: Yarrabilba". Logan City Council. 1 October 2008. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- Dunn, Peter (7 August 2000). "Camp Cable". Australia at War. Archived from the original on 8 August 2009. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- "Vicksburg (mascot) B: Vicksburg, Mississippi Aug 1940 D: Southport, QLD, 8 Oct 1944 Camp Cable (memorial) Park, Beaudesert". Archived from the original on 23 December 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- "Homminga, Wellington Francis (Interview outline and video), 2009". Veterans History Project collection, RHC-27. Grand Valley State University. University Libraries. Special Collections & University Archives. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Camp Cable near Logan Village, south of Brisbane". 7 August 2000. Archived from the original on 21 December 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- "Buna". Archived from the original on 29 August 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). The South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne: Grayflower. OCLC 7185705.

- Smith, Michael T. (28 January 2003). Bloody Ridge: The Battle That Saved Guadalcanal. New York: Pocket. ISBN 978-0-7434-6321-8. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018.

- "Papuan Campaign". Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- "World War II: Buna Mission". Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- "U.S. Army Divisions in World War II". Archived from the original on 28 September 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- Samuel Milner (1957). "United States Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific. The Japanese Offensive Collapses". Archived from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- Samuel Milner (1957). "United States Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific. Victory in Papua". Archived from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- Gailey, Harry (2000). Macarthur Strikes Back. Novato: Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-702-8.

- "PNG Treks - Kapa Kapa Track -Getaway Trekking". Getaway Trekking. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- Larrabee, Eric (2004). Commander in Chief: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, His Lieutenants, and Their War. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-455-8.

- Lunney, Bill; Finch, Frank (1995). Forgotten Fleet: a history of the part played by Australian men and ships in the U.S. Army Small Ships Section in New Guinea, 1942-1945. Medowie, NSW, Australia: Forfleet Publishing. pp. 20–24, 143. ISBN 0646260480. LCCN 96150459.

- Budge, Kent G. "Harding, Edwin Forrest (1886–1970)". The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- "Papuan Campaign – The Battle of Buna". The 32D Infantry Division in World War II The 'Red Arrow'. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- "Table of Strengths and Casualties during the Battle of Buna-Sanananda". The 32nd Infantry Division in World War II "The Red Arrow": The Papuan Campaign – The Battle of Sanananda. 15 March 1999. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- "PNG Treks—Kapa Kapa Track". Getaway Trekking. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- Mages, Robert (25 October 2009). "One Green Hell". U.S. Army Military History Institute. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "Back to Australia – Rehabilitation and Training". The 32D Infantry Division in World War II "The Red Arrow". Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Miller, John, Jr. (1959). "Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul". United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. p. 418. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

-

- Shaw, Henry I.; Douglas T. Kane (1963). "Volume II: Isolation of Rabaul". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Archived from the original on 20 November 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- Miller, CARTWHEEL: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 296

- Robert Ross Smith (1953). "The US Army in World War II: the approach to the Philippines (Chapters V to VIII)". Archived from the original on 18 February 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- Fenton, Damien. "Remembering the war in New Guinea". Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Ramos, Pedronio O. "San Nicolas, Pangasinan: Our Kind of Town". Archived from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- "Famous 32nd". The West Australian. 21 July 1945. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- "32nd Infantry Division". Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- "U.S. Army Divisions in World War Ii". Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- "Red Arrow Division Sets Combat Record". Red Arrow Division. 6 August 1945. Archived from the original on 4 November 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- "Pearl Harbor To Guadalcanal, History of the Marine Corps Operations in World War II, Volume I, p. 284". Archived from the original on 28 March 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- Milner, Samuel (1972). Victory in Papua. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History.

- Algeria-French Morocco. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-11. Archived from the original on 5 April 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- "WW II newspaper 32nd Red Arrow Division The Stalker". Worthopedia – Price Guide. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- "His Song Marches On". Portage Daily Register. 30 June 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- Sayers, Stuart (1980). Ned Herring: A Life of Lieutenant-General the Honorable Sir Edmund Herring KCMG, KBE, MC, ED. K St J, MA, DCL. Melbourne: Hyland House. ISBN 0-908090-25-0.

- "AIF Gets Full Praise For New Guinea". The Argus. 26 November 1949. p. 1. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- Letter, Eichelberger to Herring, 27 November 1959, Herring Papers, State Library of Victoria MSS11355.

- Blakeley, Herbert W. (6 May 1943). "The 32d Infantry Division in World War II (General Orders Number 21, War Department)". pp. 130, 131. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- Timothy Aumiller, 'Infantry Division Components of the U.S. Army 1917-2004, Tiger Lily Publications LLC, 2004, 75.

- Toepel & Kuehn 1960, pp. 516–517.

- Theobald 1964, pp. 615–616.

- "Organization of The 32nd 'Red Arrow' Infantry Division During the Berlin Crisis". The 32nd 'Red Arrow' Veteran Association. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- Sommers, Larry (19 February 2009). "Wisconsin to deploy largest force since WWII". Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- "Red Arrow Highway Morning". Star. 21 May 2006. p. 12. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ""Thirty-second Division Memorial Highway" Waymark". Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- "A Little Bit of History" (PDF). p. 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- "Manitowoc, WI: Red Arrow Park". Retrieved 9 September 2020.

Bibliography

- Toepel, M.G.; Kuehn, Hazel L., eds. (1960). The Wisconsin blue book, 1960. State of Wisconsin.

- Theobald, H. Rupert, ed. (1964). The Wisconsin blue book, 1964. State of Wisconsin.

Recommended readings

- The Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States U.S. Government Printing Office, 1950 reproduced at the United States Army Center of Military History.

- Anders, Leslie (1985). Gentle Knight: The Life and Times of Major General Edwin Forrest Harding. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-314-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 32nd Infantry Division (United States). |

- Wisconsin Military History Co. D, 2/128th Infantry

- 32nd Infantry Brigade (Light) (Separate)

- The History of Nº 435907 U.S. 2½ Ton 6x6 Trucks of World War II

- Henry's answers about his time during WWII

- The 32nd Division in the First World War

- Heroes: the Army Personal story of Donald C. Boyd

- Interview With Michael A. Catera Rutgers Oral History Archives, New Brunswick History Department

- Kokoda Trail

- Grand Valley State University Veteran's Oral History Project—126th Infantry Regiment

- Camp Cable monument

- Project PRIAM – WWII 32nd Infantry Division MIAs

- Red Arrow History Video produced by Wisconsin Public Television

- History of the 107th Combat Engineers