2019 Arkansas River floods

Between May and June 2019, an extended sequence of heavy rainfall events over the South Central United States caused historic flooding along the Arkansas River and its tributaries. Major and record river flooding occurred primarily in northeastern Oklahoma, and the elevated flows continued downstream into Arkansas where the caused additional inundation. Antecedent soil moisture levels and water levels in lakes and streams were already high from previous rains, priming the region for significant runoff and flooding. The prolonged combination of high atmospheric moisture and a sustained weather pattern extending across the continental United States led to frequent high-yield rainfall over the Arkansas River watershed. The overarching weather pattern allowed moisture levels to quickly rebound after each sequential rainfall episode. With soils already saturated, the excess precipitation became surface runoff and flowed into the already elevated lakes and streams. Most rainfall occurred in connection with a series of repeated thunderstorms between May 19–21, which was then followed by additional rains that kept streams within flood stage.

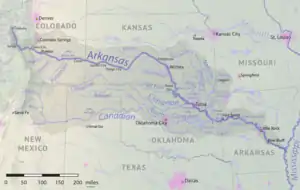

MODIS satellite image showing flooding along the Arkansas River on May 27 | |

| Date | May 18, 2019–June 14, 2019 |

|---|---|

| Location | Eastern Oklahoma, western Arkansas, southeastern Kansas, southwestern Missouri |

| Deaths | 5 total |

| Property damage | $3 billion (2019 USD)[note 1] |

Flooding in the Arkansas River basin caused an estimated $3 billion in damage and killed five people. The initial episode of torrential rainfall prompted the issuance of two flash flood emergencies for several counties in eastern Oklahoma on May 20, with numerous water rescues occurring during the event. Several reservoirs in eastern Oklahoma filled over capacity and reached record levels, requiring large releases of water to alleviate the dangerously high storage of water. Repeated rains continued to keep the reservoirs filled, necessitating further releases of water. The prolonged release of reservoir water combined with surface runoff to cause near-record to record flooding along the Arkansas River. Parts of the Tulsa metropolitan area and entire towns near swollen rivers were inundated. In some locations the Arkansas River backed upstream into its tributaries, causing major flooding. The bulge of elevated water levels that began in Oklahoma flowed downstream into Arkansas by May 23, breaching three levees along the Arkansas River and inundating numerous buildings. In Van Buren, the flood was assessed by the United States Geological Survey as a 1 in 200 year flood event.[note 2] Federal major disaster declarations and statewide states of emergencies were declared for Oklahoma and Arkansas.

Meteorological history

Across the continental United States, 12 months preceding May 2019 were the wettest in 124 years of recordkeeping,[2] in line with a longer-term trend of increasing precipitation and heavy rainfall events due to climate change.[3] Soil moisture and water levels in lakes and streams across the Southern Plains were high heading into May. During the latter half of May 2019, an active weather pattern became established over the United States, characterized by the juxtaposition of pronounced trough over the western half of the country and ridging over the southern and southeastern United States.[4] This configuration was favorable for frequent rainfalls over the Southern Plains,[4] placing the jet stream in a position to draw the warm and moist air mass atop the Gulf of Mexico northward.[1]:4 Atmospheric moisture was also atypically high during this period, with precipitable water content persisting between 1.5–2 in (38–51 mm), thereby increasing the precipitation potential of each individual shower and thunderstorm.[5][4] The first rains associated with the flood occurred on May 18, when a squall line moved across eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas. Additional showers immediately preceding and succeeding the squall enhanced rainfall totals.[5]:23

Between May 20–21, another storm system moved from the Rocky Mountains into Oklahoma. A warm front associated with the complex moved across the state during the daytime on May 20, followed by a cold front that swept eastwards across the state between the evening of May 20 into the following morning. This produced several episodes of severe thunderstorms enhanced by the confluence of the moist, warm, and unstable airmass ahead of the storm system.[6] Initially isolated thunderstorms over eastern Oklahoma coalesced into a line, with new storm cells training repeatedly tracking over the same locations as the line slowly moved east. The complex combined with another cluster of storms over central Oklahoma and tracked northeast, causing further rainfall before dissipating. Another squall line was generated by the storm system as the associated upper-level low moved into Kansas, sweeping through eastern Oklahoma and northwestern Arkansas on the morning of May 21 with its heaviest rains overlapping the same areas affected by the earlier storms.[5]:23 Most of the rainfall associated with the flood event occurred during a 36-hour period between May 19–21 in a region spanning from northeastern Oklahoma to northwestern Arkansas.[1]:1 Lesser rainfall events followed the primary rainfall event, keeping rivers in flood stage into June 2019.[1]:4 On May 22, the approach of an upper-level trough allowed moisture levels to quickly rebound in the wake of the previous day's storms. Several thunderstorms rapidly organized along Interstate 44 in Oklahoma during the late afternoon and moved towards the east-northeast. A surge of warm air and strengthening low-level winds during the nighttime hours instigated additional storm formation over the same areas.[5]:24

Two rounds of showers and thunderstorms affected eastern Oklahoma and the Ozarks between May 24–25, reaping a moist atmosphere characterized by precipitable water levels at least two standard deviations above normal over north-central Oklahoma and south-central Kansas. Widespread 1.5–4 in (38–102 mm) rainfalls occurred across the upper Arkansas River basin.[5]:30 The dominant trough over the western United States persisted, maintaining a southwesterly wind across the Southern Plains along which storms would travel. In the pre-dawn hours of May 26, a bow echo tracked across Oklahoma into Kansas, primarily affecting areas north of Interstate 40 and the Tulsa metropolitan area with severe weather and 1–3 in (25–76 mm) of rainfall. Two more periods of rainfall occurred on May 26, producing 0.5–3 in (13–76 mm) of rainfall along the Kansas–Oklahoma border.[5]:31 More rain fell ahead of a slow-moving cold front between May 28–30 over Oklahoma and Arkansas, with localized totals of 2–4 in (51–102 mm); this event was concentrated further southeast of the earlier rains, primarily affecting southeastern and east-central Oklahoma and northwestern Arkansas.[5]:34

Impact and aftermath

The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) estimated that flooding in the Arkansas River basin caused $3 billion in damage, with a 95% confidence interval between $1.8–$5.3 billion. Five people were killed by the floods.[7] Between May 18–30, 6–16 in (150–410 mm) of rain fell along and northwest of a line from Okmulgee, Oklahoma to near Bentonville, Arkansas, with 3–5 in (76–127 mm) of rain occurring at points southeast of this region.[4] The rains also extended into southern Kansas and southwestern Missouri.[5]:35 Rainfall totals of 10–16 in (250–410 mm) were widespread across southern Kansas and northern Oklahoma.[4] Some areas of Oklahoma received 22 in (560 mm) of rainfall in total, representing the highest accumulated rainfall during the flood event.[1]:1 Talala, Oklahoma, recorded more than twice its average May rainfall in a single week.[8] While most of the contributing rains fell between May 19–21, river flood crests occurred between May 26–June 4.[1]:1 Within the warning region of the National Weather Service office in Tulsa, Oklahoma, at least one river was at flood stage between the evening of May 20 and the morning of June 13.[5]:20 Kansas and Missouri ultimately had their wettest Mays on record, with Oklahoma experiencing its second-highest May totals and Arkansas recording its ninth-highest.[1]:4

Oklahoma

Six United States Army Corps of Engineers reservoirs in northeastern Oklahoma set records for water volume during the floods: Birch Lake, Lake Hudson, Kaw Lake, Keystone Lake, Oologah Lake, and Skiatook Lake. The National Weather Service cataloged 31 river flood events at 22 river forecast points in eastern Oklahoma. Two of these instances were at record flood stage, including the Arkansas River near Ponca City; 25 of the 31 flood events were classified as major floods. Several river gauges recorded flooding conditions lasting for more than a week; the longest flood was documented along the Arkansas River near Muskogee, which remained above flood stage for 22 days and 5 hours.[4] Numerous state and U.S. highways were closed by the Oklahoma Department of Transportation at various points due to flooding.[9] Over a thousand homes were affected by flooding associated with the Arkansas River.[10] Throughout the state, 4 people were killed and 87 others were injured.[11][4][12][13]

Prior to the primary flood event, water levels along the Arkansas River at Muskogee had remained just below flood stage. The first round of rainfall on May 18 produced widespread totals of 0.5–1 in (13–25 mm) across eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas, raising the Arkansas River into flood stage.[5]:23 With the threat of flood and a tornado outbreak looming, many events scheduled for the evening of May 20 were cancelled or rescheduled.[5]:24 That evening, heavy and persistent rainfall from a slow-moving line of thunderstorms caused widespread flash flooding primarily along a line from Bristow to Miami and areas northwest, submerging roadways and leading to several evacuations and water rescues. At 11:14 p.m. CDT on May 20, National Weather Service Tulsa issued a flash flood emergency for southern Osage, Pawnee, northwestern Tulsa County, Oklahoma, and Washington counties. Another flash flood emergency was issued 30 minutes later for western Mayes, southeastern Osage, Rogers, northern Wagoner, and Tulsa counties.[5]:23

By 7 a.m. CDT on May 21 between 4–8 in (100–200 mm) had fallen across north-central and northeastern Oklahoma. A station in Pawnee recorded the highest 24-hour total with 9.52 in (242 mm).[5]:24 More than 6 in (150 mm) of rain fell in a 24-hour period of May 21 over parts of Tulsa and Stillwater.[1]:4 Atop saturated soils, the rainfall became surface runoff which flowed into streams and the United States Army Corps of Engineers's flood control pools. Flooding affected the watersheds of the upper Arkansas, Neosho, and Verdigris rivers, which all reach a confluence in Muskogee.[5]:24 The submarine USS Batfish (SS-310) at the Muskogee War Memorial Park briefly took on water due to the swollen Arkansas River.[14] Flash flooding and broader areal flooding caused Bird Creek to inundate areas around Skiatook. Near Avant, the creek rose 30.5 ft (9.3 m) in 12 hours, cresting at 36.52 ft (11.13 m) on the morning of May 21. Water releases were necessary to relieve dangerously high lake levels in the absence of surcharge capacity, worsening flooding downstream of Pensacola Dam and Kerr Dam.[5]:24 Residents were forced to evacuate Webbers Falls on May 22 as the flooded river began to overtake homes.[15] A voluntary evacuation was declared for residents of Broken Arrow living within the 100-year floodplain near the Arkansas River.[16] Flash flooding following 6 in (150 mm) of rain in El Reno led to six water rescues.[17]

The water levels in Kaw, Keystone, and Oologah lakes began to exceed their flood control limits after the May 22–23 rainfall. Kaw Lake's depth reached 112.16% of its flood pool capacity on May 24, causing the associated surcharge pool to completely fill; similar circumstances were present at Keystone and Ooologah lakes, prompting releases of the excess water downstream.[5]:25 Releases at the Keystone Dam into the Arkansas River reached flow rates more than double the flow rates at Niagara Falls.[15] The Keystone Dam water release was its second largest on record and contributed to the Arkansas River reaching major flood stage in Tulsa during the afternoon of May 23.[5]:25 Tulsa city officials recommended that people living west of Downtown Tulsa evacuate in acknowledgement of the old age of the levees protecting the city from the swollen Arkansas River. The town of Braggs, approximately 55 mi (89 km) southeast of Tulsa, lost power and was fully enveloped by floodwaters.[11] Widespread flooding occurred across numerous streams as the May 22–23 rains further exacerbated the elevated river stages from the earlier extreme rainfall event. The entire stretch of the Arkansas River within the warning region of National Weather Service Tulsa—spanning 396 mi (637 km)–experienced a major flood. All barge traffic along the McClellan–Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System was suspended on May 22. Two unoccupied barges tethered together broke free from their moorings at the Port of Muskogee that evening, haphazardly floating downstream. They were briefly obstructed by rocks before continuing downstream as the river rose, eventually colliding with the lock and dam system at Webbers Falls Lake and capsizing at around noon on May 23.[5]:25 All residents in Moffett along the Arkansas River were ordered to evacuate on May 24.[18] The Neosho River crested at 25.5 ft (7.8 m) in Miami on May 24. Southern parts of the city were submerged, with some roads under 4 ft (1.2 m) underwater. Thirty water rescues took place in Miami during the floods.[19]

By May 25, the excess surface runoff flowing into the Arkansas River caused the river to begin piling water upstream into its tributaries. The Poteau River flooded in this manner near Panama and rises were documented upstream to Lake Wister. Lake Hudson reached a record height on May 24 despite concurrent water releases at Kerr Dam. Fort Gibson Lake crested a day later while excess water was being released via Fort Gibson Dam.[5]:30 Widespread runoff from the May 26 caused Keystone Lake to rise further, reaching a record elevation of 757.19 ft (230.79 m) two days later. A second water release from the dam took place on May 29, causing a 23.41 ft (7.14 m)-crest on the Arkansas River in Tulsa; this was the river's second highest crest in the city on record.[1]:1 A neighborhood on the western side of Sand Springs were flooded by both water releases from Keystone Lake.[20] Homes in southern Tulsa and Bixby were also inundated. Two people drowned in Tulsa on May 26 to the floodwaters along the Arkansas River.[4] Other locations along the Arkansas River downstream also set records or near-records for river heights. In addition to Keystone, six other lakes crested between May 25–27, with three setting new pools of record. Releases from Oologah Lake caused major flooding along the Verdigris River near Claremore.[5]:31 Saturated soils and high river levels quickened the development of flash flooding, leading to the issuance of a flash flood emergency for northwestern Muskogee, central Okfuskee, and Okmulgee counties on May 29 following another round of heavy rainfall. Although some lakes and streams had begun to recede, the new rains caused water levels to rise once more along the Arkansas River and Poteau River. Birch Lake exceeded its flood control pool for a second time while Lake Eufaula did so for its first time, requiring another water release into the Arkansas River.[5]:35

Governor of Oklahoma Kevin Stitt declared a state of emergency for all 77 counties on May 24, augmenting an earlier state of emergency that had been in place for 52 counties since the beginning of the month. U.S. President Donald Trump approved a Major Disaster Declaration for Oklahoma on June 1 with an incident period from May 7–June 9.[21] United States National Guard helicopters dropped 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) sandbags to reinforce strained levees.[22] The City of Tulsa began allowing flood-stricken evacuees back to their homes on June 1, following over a week of displacement.[23]

Arkansas

The swollen streams in northeastern Oklahoma led to record flows in Arkansas throughout the Arkansas River Valley as the elevated bulge of water moved downstream, combining both surface runoff and large releases of water from upstream dams.[24] On May 22, officials from the Army Corps of Engineers warned of potentially record-breaking flood levels and flow rates in Arkansas, and urged people in floodplains and other flood-prone areas to relocate livestock and other belongings.[25] The floods reached Fort Smith along the Arkansas–Oklahoma border on May 23.[26]

Six of seven streamgages along the Arkansas River surveyed by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in Arkansas recorded their highest streamflows on record. The flooding was considered a 1 in 200 year event near Van Buren, Arkansas, where the river reached a peak streamflow of 570,000 cu ft/s (16,000 m3/s).[1]:7 The river at Van Buren reached 40.79 in (1.036 m), topping the previous record of 38.1 ft (11.6 m).[18] Water from the Arkansas River backed upstream into Lee Creek, causing major flooding.[5]:25 At Dardanelle, the flooding reached magnitudes with return periods exceeding 200 years.[1]:7 At least three levees were breached along the Arkansas River between Fort Smith and Little Rock, with another five sustaining substantial damage.[1]:1 The breach of a 40 ft (12 m)-section of levee near Dardanelle in Yell County prompted evacuations, threatening 300–400 homes and 5,700 people.[15][27] While the homes were ultimately not affected, the flooding significantly impacted adjacent farmland. Arkansas Highway 155 sustained major damage. Other highways were also flooded, including Arkansas Highway 22, where one person died on May 28 after circumnavigating a flood barricade. Highway 22 remained closed until June 4, three days after the Arkansas River initially crested.[15] Parks, homes, and businesses in Fort Smith were overtaken by the river, leaving parts of the city accessible only by boat.[18][22] In total, 500 homes in Fort Smith were affected.[18]

Evacuations occurred in Faulkner County due to the rise of Lake Conway and the potential breach of the Lollie Levee. The lake flooded shoreline homes while the Lollie Levee maintained integrity.[15] Mandatory evacuations were also ordered in parts of Jefferson County.[27] On May 28, a partition of levee 80 ft (24 m) wide and 12 ft (3.7 m) high in Crawford County slumped against the rising Arkansas River, threatening 250 people in 152 residences; the levee remained intact as the river crested on June 1.[18] Governor of Arkansas Asa Hutchinson declared a state of emergency for the entire state on May 21.[21] Hutchinson estimated that flooding caused the state economy to lose $23 million per day. On May 29, $350,000 in state financial assistance was committed towards flood mitigation.[26] President Donald Trump approved a Major Disaster Declaration for Kansas on June 8 with an incident period from May 21–June 14.[21] The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development disbursed $9 million in recovery fund grants to twelve Arkansas counties in December 2019.[18]

See also

- Tornado outbreak sequence of May 2019 – occurred in conjunction with the flooding

- Concurrent floods in the United States:

- 2010 Arkansas floods – deadly flash flood along the Little Missouri and Caddo rivers

- Climate change in Arkansas

Notes

- All damage totals in 2019 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

- The return period refers to the probability of a given flood peak occurring over a period of time. A 100-year event, by definition, has a 1% chance happening in a specific year, although it is possible for such events to happen more than once over 100 years.[1]

References

- Lewis, Jason M.; Trevisan, Adam R. (2019). Peak Streamflow and Stages at Selected Streamgages on the Arkansas River in Oklahoma and Arkansas, May to June 2019 (PDF) (Report). Reston, Virginia: United States Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/ofr20191129. ISSN 2331-1258. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2019–1129. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Flooding Along the Arkansas River". Earth Observatory. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. May 30, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Record-Setting Precipitation Leaves U.S. Soils Soggy". Earth Observatory. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. May 27, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Storm Event Report for Flood in Tulsa County, OK. Storm Events Database (Storm Event). Asheville, North Carolina: National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Piltz, Steven F.; McGavcock, Nicole (May 2019). Monthly Report of River and Flood Conditions (PDF) (Report). Tulsa, Oklahoma: National Weather Service Tulsa, OK. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Storm Event Report for Flood in Osage County, OK. Storm Events Database (Storm Event). Asheville, North Carolina: National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Events". Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters. Asheville, North Carolina: NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Cappucci, Matthew (May 24, 2019). "A week of relentless rain is terrorizing Oklahoma, swallowing homes and sounding flood sirens". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved March 7, 2020. (subscription required)

- "Update: Oklahoma 72 from East 201st South near Coweta is open; road closures remain elsewhere". Tulsa World. Tulsa, Oklahoma. BH Media Group, Inc. May 31, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Grimwood, Harrison (May 31, 2019). "'A multiyear process for recovery': Flooding continues as Corps increases Keystone Dam output". Tulsa World. Tulsa, Oklahoma. BH Media Group, Inc. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Oklahoma neighborhoods prepare to evacuate as flooding tests levees". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California: Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. May 25, 2019.

- Storm Event Report for Flood in Lincoln County, OK. Storm Events Database (Storm Event). Asheville, North Carolina: National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Storm Event Report for Flood in Payne County, OK. Storm Events Database (Storm Event). Asheville, North Carolina: National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "UPDATE: Efforts Underway To Protect USS Batfish In Muskogee Flooding". NewsOn6.com. Tulsa, Oklahoma: Griffin Communications. May 24, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "NWS Little Rock, AR - Historic Flooding in 2019 (Arkansas River/Tropical Storm Barry)". Historic Events in Arkansas. Little Rock, Arkansas: National Weather Service Little Rock, AR. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "City Of Broken Arrow Urges Voluntary Evacuations In 100-Year Flood Plain". NewsOn6.com. Tulsa, Oklahoma: Griffin Communications. May 23, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Villareal, Mireya (May 21, 2019). "Oklahoma flooding leaves people trapped by rising waters". CBS News. CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Bryan, Max (December 31, 2019). "Arkansas River flood No. 1 story of 2019". Times Record. Fort Smith, Arkansas: Gannett Co., Inc. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Stogsdill, Sheila (May 25, 2019). "Miami police crack down on road barricade violations while residents go into 'survival mode' amid unrelenting flooding". Tulsa World. Tulsa, Oklahoma: BH Media Group, Inc. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Canfield, Kevin (May 28, 2019). "Angry residents west of Sand Springs say they didn't have enough warning to evacuate". Tulsa World. Tulsa, Oklahoma: BH Media Group, Inc. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "May 2019 Climate and Hydrology Summary". Tulsa, Oklahoma: National Weather Service Tulsa, OK. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Arkansas River communities scramble to hold historic flooding at bay". CBS News. CBS Interactive Inc. May 29, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "'It has been quite a week and a half': Residents returning home in some areas". Tulsa World. Tulsa, Oklahoma: BH Media Group, Inc. June 1, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Storm Event Report for Flood in Sebastian County, AR. Storm Events Database (Storm Event). Asheville, North Carolina: National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Rddad, Youssef (May 22, 2019). "Officials warn of potentially historic flooding as Arkansas River swells". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock, Arkansas: Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Inc. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Bryan, Max (May 31, 2019). "Governor, senators expect FEMA assistance for Fort Smith area". Times Record. Fort Smith, Arkansas: Gannett Co., Inc. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Levee in North Little Rock not breached despite earlier report, official says". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock, Texas: Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Inc. May 31, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2020.