Little Rock, Arkansas

Little Rock is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Arkansas. As the county seat of Pulaski County, the city was incorporated on November 7, 1831, on the south bank of the Arkansas River close to the state's geographic center. The city derived its name from a rock formation along the river, named the "Little Rock" (French: La Petite Roche) by the French explorer Jean-Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe in the 1720s. The capital of the Arkansas Territory was moved to Little Rock from Arkansas Post in 1821. The city's population was 197,312 in 2019 according to the United States Census Bureau. The six-county Little Rock-North Little Rock-Conway, AR Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) is ranked 78th in terms of population in the United States with 738,344 residents according to the 2017 estimate by the United States Census Bureau.[3][4]

Little Rock, Arkansas | |

|---|---|

| City of Little Rock | |

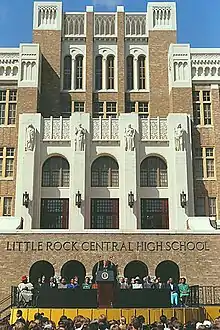

Clockwise from top: Little Rock skyline, Arkansas Razorbacks football in War Memorial Stadium, the Arkansas State Capitol, River Market District, Little Rock Central High School, and the William J. Clinton Presidential Library | |

Flag  Logo | |

| Nickname(s): The Rock, Rock Town, LR | |

Location within Pulaski County | |

Little Rock Location within Arkansas  Little Rock Location within the United States | |

| Coordinates: 34°44′10″N 92°19′52″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Pulaski |

| Township | Big Rock |

| Founded | June 1, 1821 |

| Incorporated (town) | November 7, 1831 |

| Incorporated (city) | November 2, 1835 |

| Named for | French: La Petite Roche (The "Little Rock") |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-manager |

| • Mayor | Frank Scott Jr. (D) |

| • Council | Little Rock Board of Directors |

| Area | |

| • State capital city | 122.95 sq mi (318.44 km2) |

| • Land | 119.99 sq mi (310.77 km2) |

| • Water | 2.96 sq mi (7.67 km2) |

| • Metro | 4,090.34 sq mi (10,593.94 km2) |

| Elevation | 335 ft (102 m) |

| Population | |

| • State capital city | 193,524 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 197,312 |

| • Rank | US: 126th |

| • Density | 1,644.39/sq mi (634.90/km2) |

| • Urban | 431,388 (US: 89th) |

| • Metro | 738,344 (US: 80th) |

| Demonym(s) | Little Rocker |

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| ZIP code(s) | 72002, 72103, 72201, 72202, 72204, 72205, 72206, 72207, 72209, 72210, 72211, 72212, 72223, 72227 |

| Area code(s) | 501 |

| FIPS code | 05-41000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 83350 |

| Major airport | Clinton National Airport/Adams Field (LIT) |

| Interstate Highways | I-30, I-40, I-430, I-440, I-530, I-630 |

| Other major highways | US 65, US 67, US 70, US 167, AR 107 |

| Website | www |

Little Rock is a cultural, economic, government, and transportation center within Arkansas and the South. Several cultural institutions are in Little Rock, such as the Arkansas Arts Center, the Arkansas Repertory Theatre, and the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra, in addition to hiking, boating, and other outdoor recreational opportunities. Little Rock's history is available through history museums, historic districts or neighborhoods like the Quapaw Quarter, and historic sites such as Little Rock Central High School. The city is the headquarters of Dillard's, Windstream Communications, Acxiom, Stephens Inc., University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Heifer International, Winrock International, the Clinton Foundation, and the Rose Law Firm. Other corporations, such as Amazon, Dassault Falcon Jet, LM Wind Power, Simmons Bank, Euronet Worldwide, AT&T, and Entergy have large operations in the city. State government is a large employer, with many offices downtown. Two major Interstate highways, Interstate 30 and Interstate 40, meet in Little Rock, with the Port of Little Rock serving as a shipping hub.

Etymology

Little Rock derives its name from a small rock formation on the south bank of the Arkansas River called the "Little Rock" (French: La Petite Roche). The Little Rock was used by early river traffic as a landmark and became a well-known river crossing. The Little Rock is across the river from The Big Rock, a large bluff at the edge of the river, which was once used as a rock quarry.[5]

History

Archeological artifacts provide evidence of Native Americans inhabiting Central Arkansas for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. The early inhabitants may have been the Folsom people, Bluff Dwellers, and Mississippian culture peoples who built earthwork mounds recorded in 1541 by Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto. Historical tribes of the area were the Caddo, Quapaw, Osage, Choctaw, and Cherokee.

Little Rock was named for a stone outcropping on the bank of the Arkansas River used by early travelers as a landmark.[6] It was named in 1722 by French explorer and trader Jean-Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe, marked the transition from the flat Mississippi Delta region to the Ouachita Mountain foothills. Travelers referred to the area as the "Little Rock." Though there was an effort to officially name the city "Arkopolis" upon its founding in the 1820s, and that name did appear on a few maps made by the US Geological Survey, the name Little Rock is eventually what stuck.[7][8][9]

Geography

Little Rock is located at 34°44′10″N 92°19′52″W (34.736009, −92.331122).[10]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 116.8 square miles (303 km2), of which 116.2 square miles (301 km2) is land and 0.6 square miles (1.6 km2) (0.52%) is water.

Little Rock is located on the south bank of the Arkansas River in Central Arkansas. Fourche Creek and Rock Creek run through the city, and flow into the river. The western part of the city is located in the foothills of the Ouachita Mountains. Northwest of the city limits are Pinnacle Mountain and Lake Maumelle, which provides Little Rock's drinking water.

The city of North Little Rock is located just across the river from Little Rock, but it is a separate city. North Little Rock was once the 8th ward of Little Rock. An Arkansas Supreme Court decision on February 6, 1904, allowed the ward to merge with the neighboring town of North Little Rock. The merged town quickly renamed itself Argenta (the local name for the former 8th Ward), but returned to its original name in October 1917.[11]

Neighborhoods

- Applegate

- Birchwood

- Breckenridge

- Briarwood

- Broadmoor

- Bryce's Creek

- Capitol-Main Historic District

- Capitol View/Stifft's Station

- Central High School Historic District

- Chenal Valley

- Cloverdale

- Colony West

- Downtown

- East End

- Fair Park

- Geyer Springs

- Governor's Mansion

- Granite Mountain

- Gum Springs

- Hanger Hill

- Hall High

- The Heights

- Highland Park

- Hillcrest

- John Barrow

- Leawood

- Mabelvale

- MacArthur Park

- Marshall Square

- Otter Creek

- Pankey

- Paul Laurence Dunbar School

- Pinnacle Valley

- Pleasant Valley

- Pulaski Heights

- Quapaw Quarter

- Riverdale

- Robinwood

- Rosedale

- Scott Street

- St. Charles

- South End

- South Main Street (apartments)

- South Main Street (residential)

- South Little Rock

- Southwest Little Rock

- Stagecoach

- Sturbridge

- University Park

- Walton Heights

- Wakefield

- West End

- Woodlands Edge

Metropolitan area

The 2017 U.S. Census population estimate for the Little Rock-North Little Rock-Conway, AR Metropolitan Statistical Area was 738,344. The MSA covers the following counties: Pulaski, Faulkner, Grant, Lonoke, Perry, and Saline. The largest cities are Little Rock, North Little Rock, Conway, Jacksonville, Benton, Sherwood, Cabot, Maumelle, and Bryant.

Climate

Little Rock lies in the humid subtropical climate zone, with hot, humid summers and cool winters with usually little snow. It has experienced temperatures as low as −12 °F (−24 °C), which was recorded on February 12, 1899, and as high as 114 °F (46 °C), which was recorded on August 3, 2011.[13]

| Climate data for Little Rock (Little Rock Nat'l Airport), 1981−2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1875−present[lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 83 (28) |

87 (31) |

91 (33) |

95 (35) |

98 (37) |

107 (42) |

112 (44) |

114 (46) |

106 (41) |

98 (37) |

86 (30) |

81 (27) |

114 (46) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 71.6 (22.0) |

75.9 (24.4) |

81.6 (27.6) |

86.4 (30.2) |

91.3 (32.9) |

96.2 (35.7) |

100.3 (37.9) |

100.9 (38.3) |

96.1 (35.6) |

88.5 (31.4) |

80.0 (26.7) |

71.9 (22.2) |

102.6 (39.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 50.5 (10.3) |

55.1 (12.8) |

64.0 (17.8) |

73.1 (22.8) |

81.1 (27.3) |

88.9 (31.6) |

92.5 (33.6) |

92.6 (33.7) |

85.6 (29.8) |

74.8 (23.8) |

63.0 (17.2) |

52.3 (11.3) |

72.9 (22.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 31.2 (−0.4) |

34.5 (1.4) |

42.7 (5.9) |

51.0 (10.6) |

61.1 (16.2) |

69.4 (20.8) |

73.2 (22.9) |

72.4 (22.4) |

64.5 (18.1) |

52.6 (11.4) |

42.2 (5.7) |

33.7 (0.9) |

52.5 (11.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 15.5 (−9.2) |

19.3 (−7.1) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

35.8 (2.1) |

47.0 (8.3) |

58.0 (14.4) |

64.8 (18.2) |

62.9 (17.2) |

48.2 (9.0) |

36.8 (2.7) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

18.2 (−7.7) |

11.3 (−11.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −8 (−22) |

−12 (−24) |

11 (−12) |

28 (−2) |

38 (3) |

46 (8) |

54 (12) |

52 (11) |

37 (3) |

27 (−3) |

10 (−12) |

−1 (−18) |

−12 (−24) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.55 (90) |

3.66 (93) |

4.68 (119) |

5.14 (131) |

4.87 (124) |

3.65 (93) |

3.27 (83) |

2.59 (66) |

3.18 (81) |

4.91 (125) |

5.28 (134) |

4.97 (126) |

49.75 (1,264) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.6 (4.1) |

1.3 (3.3) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

trace | 0.2 (0.51) |

3.5 (8.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.9 | 9.1 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 8.7 | 8.2 | 6.4 | 7.3 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 105.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 180.9 | 188.2 | 244.5 | 276.7 | 325.3 | 346.2 | 351.0 | 323.0 | 271.9 | 251.0 | 176.9 | 166.2 | 3,101.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 58 | 62 | 66 | 71 | 75 | 80 | 80 | 78 | 73 | 72 | 57 | 54 | 70 |

| Source: NOAA (sun 1961−1990 at North Little Rock Airport),[14][15][16] The Weather Channel[17] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 2,167 | — | |

| 1860 | 3,727 | 72.0% | |

| 1870 | 12,380 | 232.2% | |

| 1880 | 13,138 | 6.1% | |

| 1890 | 25,874 | 96.9% | |

| 1900 | 38,307 | 48.1% | |

| 1910 | 45,941 | 19.9% | |

| 1920 | 65,142 | 41.8% | |

| 1930 | 81,679 | 25.4% | |

| 1940 | 88,039 | 7.8% | |

| 1950 | 102,213 | 16.1% | |

| 1960 | 107,813 | 5.5% | |

| 1970 | 132,483 | 22.9% | |

| 1980 | 159,151 | 20.1% | |

| 1990 | 175,795 | 10.5% | |

| 2000 | 183,133 | 4.2% | |

| 2010 | 193,524 | 5.7% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 197,312 | [2] | 2.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

As of the 2005–2007 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, White Americans made up 52.7% of Little Rock's population; of which 49.4% were non-Hispanic Whites, down from 74.1% in 1970.[19] Blacks or African Americans made up 42.1% of Little Rock's population, with 42.0% being non-Hispanic blacks. American Indians made up 0.4% of Little Rock's population while Asian Americans made up 2.1% of the city's population. Pacific Islander Americans made up less than 0.1% of the city's population. Individuals from some other race made up 1.2% of the city's population; of which 0.2% were non-Hispanic. Individuals from two or more races made up 1.4% of the city's population; of which 1.1% were non-Hispanic. In addition, Hispanics and Latinos made up 4.7% of Little Rock's population.

.png.webp)

As of the 2010 census, there were 193,524 people, 82,018 households, and 47,799 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,576.0 people per square mile (608.5/km2). There were 91,288 housing units at an average density of 769.1 per square mile (296.95/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 48.9% White, 42.3% Black, 0.4% Native American, 2.7% Asian, 0.08% Pacific Islander, 3.9% from other races, and 1.7% from two or more races. 6.8% of the population is Hispanic or Latino.

There were 82,018 households, out of which 30.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.6% were married couples living together, 17.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.7% were non-families. 34.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 3.00.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 24.7% under the age of 18, 10.0% from 18 to 24, 31.7% from 25 to 44, 22.0% from 45 to 64, and 11.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $37,572, and the median income for a family was $47,446. Males had a median income of $35,689 versus $26,802 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,209. 14.3% of the population is below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 20.9% of those under the age of 18 and 9.0% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.

Crime

In the late 1980s, Little Rock experienced a 51% increase in murder arrests of children under 17, and a 40% increase in among 18- to 24-year-olds. From 1988 to 1992, murder arrests of youths under 18 increased by 256%.[20] By the end of 1992, Little Rock reached a record of 61 homicides,[21] but in 1993 surpassed it with 76.[22] It was one of the highest per-capita homicide rates in the country, placing Little Rock fifth in Money Magazine's 1994 list of most dangerous cities.[20] In July 2017, a shootout occurred at the Power Ultra Lounge nightclub in downtown Little Rock. Although there were no deaths, twenty-eight people were injured and one hospitalized.

Economy

Dillard's Department Stores, Windstream Communications and Acxiom, Simmons Bank, Bank of the Ozarks, Rose Law Firm, Central Flying Service and large brokerage Stephens Inc. are headquartered in Little Rock.

Large companies headquartered in other cities but with a large presence in Little Rock are Dassault Falcon Jet near Little Rock National Airport in the eastern part of the city, Fidelity National Information Services in northwestern Little Rock, and Welspun Corp in Southeast Little Rock.

Little Rock and its surroundings are the headquarters for some of the largest non-profit organizations in the world, such as Winrock International, Heifer International, the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, Clinton Foundation, Lions World Services for the Blind, Clinton Presidential Center, Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, FamilyLife, Audubon Arkansas, and The Nature Conservancy.

Associations, such as the American Taekwondo Association, Arkansas Hospital Association, and the Quapaw Quarter Association.

Arkansas Blue Cross and Blue Shield, Baptist Health Medical Center, Entergy, Dassault Falcon Jet, Siemens, AT&T Mobility, Kroger, Euronet Worldwide, L'Oréal Paris, Timex, and UAMS are employers throughout Little Rock.

One of the largest public employers in the state with over 10,552 employees, the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) and its healthcare partners—Arkansas Children's Hospital and the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System—have a total economic impact in Arkansas of about $5 billion per year. UAMS receives less than 11% of its funding from the state. Its operation is funded by payments for clinical services (64%), grants and contracts (18%), philanthropy and other (5%), and tuition and fees (2%).

The Little Rock port is an intermodal river port with a large industrial business complex. It is designated as Foreign Trade Zone 14. International corporations such as Danish manufacturer LM Glasfiber have established new facilities adjacent to the port.

Along with Louisville and Memphis, Little Rock has a branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.[23]

Arts and culture

Cultural sites in Little Rock include the following.

- Arkansas Arboretum – at Pinnacle Mountain, it has a trail with flora and tree plantings.

- Arkansas Arts Center – The state's largest art museum, containing drawings, collections, children's theater productions, works by Van Gogh, Rembrandt, and others in eight art galleries, a museum school, gift shop and restaurant.

- Community Theatre of Little Rock – Founded in 1956, it is the area's oldest performance art company.

- Arkansas Repertory Theatre – The state's largest professional, not-for-profit theatre company, in its 34th season. "The Rep" produces works such as contemporary comedies, dramas, world premiers, and dramatic literature.

- Arkansas Symphony Orchestra[24] – In its 41st season, the orchestra performs over 30 concerts a year and many events.

- Heifer International – Headquarters of the global hunger and poverty relief organization, adjacent to the Clinton Presidential Center

- Quapaw Quarter – Start of the 20th century Little Rock consists of three National Register historic districts with at least a hundred buildings on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Robinson Center Music Hall – The main performance center of the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra.

- Wildwood Park for the Arts – The largest park dedicated to the performing arts in the South. It features seasonal festivals and cultural events.

Museums

.jpg.webp)

- The Arkansas Arts Center, the state's largest cultural institution, is a museum of art and an active center for the visual and performing arts.

- The Museum of Discovery features hands-on exhibits in the fields of science, history and technology.

- The William J. Clinton Presidential Center includes the Clinton presidential library and the offices of the Clinton Foundation and the Clinton School of Public Service. The Library facility, designed by architect James Polshek, cantilevers over the Arkansas River, echoing Clinton's campaign promise of "building a bridge to the 21st century". The archives and library contains 2 million photographs, 80 million pages of documents, 21 million e-mail messages, and nearly 80,000 artifacts from the Clinton presidency. The museum within the library showcases artifacts from Clinton's term and has a full-scale replica of the Clinton-era Oval Office. Opened on November 18, 2004, the Clinton Presidential Center cost $165 million to construct and covers 150,000 square feet (14,000 m2) within a 28-acre (113,000 m2) park.

- The Historic Arkansas Museum is a regional history museum focusing primarily on the frontier time period.

- The MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History opened in 2001, the last remaining structure of the original Little Rock Arsenal and one of the oldest buildings in central Arkansas, it was the birthplace of General Douglas MacArthur who went on to be the supreme commander of US forces in the South Pacific during World War II.

- The Old State House Museum is a former state capitol building now home to a history museum focusing on Arkansas' recent history.

- The Mosaic Templars Cultural Center is a state operated history museum focusing on African American history and culture in Arkansas.

- The ESSE Purse Museum illustrates the stories of American women's lives during the 1900s through their handbags and the day-to-day items carried in them

Theatre

Founded in 1976, the Arkansas Repertory Theatre is the state's largest nonprofit professional theatre company. A member of the League of Resident Theatres (LORT D), The Rep has produced more than 300 productions, such as 40 world premieres, in its building located in downtown Little Rock. Producing Artistic Director John Miller-Stephany leads a resident staff of designers, technicians and administrators in eight to ten productions for an annual audience in excess of 70,000 for MainStage productions, educational programming and touring. The Rep produces works from contemporary comedies and dramas to world premiers and the classics of dramatic literature.

Outside magazine named Little Rock one of its 2019 Best Places to Live.[25] Dozens of parks such as Pinnacle Mountain State Park are in Little Rock.

Government

.jpg.webp)

The city has operated under the city manager form of government since November 1957. In 1993, voters approved changes from seven at-large city directors (who rated the position of mayor among themselves) to a popularly elected mayor, seven ward directors and three at-large directors. The position of mayor remained a part-time position until August 2007. At that point, voters approved making the mayor's position a full-time position with veto power, while a vice mayor is selected by and among members of the city board. The current mayor, elected in November 2018, is Frank Scott Jr., a former assistant bank executive, pastor and state highway commissioner. The current city manager is Bruce T. Moore, who is the longest-serving city manager in Little Rock history. The city employs over 2,500 individuals in 14 different departments, including the Police Department, the Fire Department, Parks and Recreation, and the Zoo.

Most Pulaski County government offices are located in the city of Little Rock, including the Quorum, Circuit, District, and Juvenile Courts; and the Assessor, County Judge, County Attorney, and Public Defenders offices.

Both the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas and the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit have judicial facilities in Little Rock. The city is served by the Little Rock Police Department.

Education

Colleges and universities

Little Rock is home to two universities that are part of the University of Arkansas System: the campuses of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences are located in the city. UAMS is Arkansas's largest basic and applied research institution, with programs in multiple myeloma, aging, and other areas.

A pair of smaller, historically black colleges, Arkansas Baptist College and Philander Smith College, affiliated with the United Methodist Church, are also in Little Rock.

Located in downtown is the Clinton School of Public Service, a branch of the University of Arkansas System, which offers master's degrees in public service.

Pulaski Technical College has two locations in Little Rock. The Pulaski Technical College Little Rock-South site houses programs in automotive technology, collision repair technology, commercial driver training, diesel technology, small engine repair technology and motorcycle/all-terrain vehicle repair technology. The Pulaski Technical College Culinary Arts and Hospitality Management Institute and The Finish Line Cafe are also located in Little Rock-South.

There is a Missionary Baptist Seminary in Little Rock associated with the American Baptist Association. The school began as Missionary Baptist College in Sheridan in Grant County.

Public schools

Little Rock is home to both the Arkansas School for the Blind (ASB) and the Arkansas School for the Deaf (ASD), which are state-run schools operated by the Board of Trustees of the ASB–ASD. In addition, eStem Public Charter High School and LISA Academy provide tuition-free public education as charter schools.

The city's comprehensive public school system is operated by the Little Rock School District (LRSD). As of 2012, the district consists of 64 schools with more schools being built. As of the 2009–2010 school year, the district has enrollment of 25,685. It has 5 high schools, 8 middle schools, 31 elementary schools, 1 early childhood (pre-kindergarten) center, 2 alternative schools, 1 adult education center, 1 accelerated learning center, 1 career-technical center, and about 3,800 employees.

LRSD public high schools include:

- Hall High School

- J. A. Fair Science and Technology Systems Magnet High School

- Little Rock Central High School

- McClellan Magnet High School

- Parkview Arts and Science Magnet High School

- Little Rock Southwest Magnet High School

The Pulaski County Special School District (PCSSD) serves parts of Little Rock. PCSSD high schools are located in the city such as:

Private schools

Various private schools are located in Little Rock, such as:

Little Rock previously had a Catholic high school for African-Americans, St. Bartholomew High School; it closed in 1964. The Catholic grade school St. Bartholomew School, also established for African-Americans, closed in 1974.[26] The Our Lady of Good Counsel School closed in 2006.[27]

Public libraries

The Central Arkansas Library System comprises the main building downtown and numerous branches throughout the city, Jacksonville, Maumelle, Perryville, Sherwood and Wrightsville. The Pulaski County Law Library is at the William H. Bowen School of Law.

Notable places

- American Taekwondo Association World Headquarters. The American Taekwondo Association [ATA] is based in Little Rock where it hosts the World Taekwondo Championships each summer. The ATA World Headquarters is also headquarters for all of the Songahm Taekwondo organizations such as the American Taekwondo Association, the Songahm Taekwondo Federation and the World Traditional Taekwondo Union. These combined organizations have millions of members in the US and worldwide.

- Arkansas River Trail

- Arkansas State Capitol – a neo-classical structure with many restored interior spaces, constructed from 1899 to 1915.

- Big Dam Bridge – The longest pedestrian/bicycle bridge in North America that has never been used by cars or trucks.

- Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Andrew (1878-1881)

- Clinton Presidential Library

- Heifer International

- Little Rock Marathon

- Little Rock Zoo – Consists of at least 725 animals and over 200 species.

- Pinnacle Mountain State Park

- Willow Springs Water Park – one of the first water theme parks in the U.S. built in 1928.

- A poster traced back to the Cicada 3301 mystery was discovered in downtown Little Rock.[28]

Sports

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arkansas Travelers | Texas League | Dickey-Stephens Park | 1963 (played as the Little Rock Travelers from 1887-1961) | 7 |

| Little Rock Rangers | USL League Two | War Memorial Stadium | 2016 | 0 |

| Little Rock Trojans | NCAA Division I (Sun Belt Conference) | Jack Stephens Center and Gary Hogan Field | 1927 | 3 |

Little Rock is home to the Arkansas Travelers. They are the AA professional Minor League Baseball affiliate of the Seattle Mariners in the Texas League. The Travelers played their last game in Little Rock at Ray Winder Field on September 3, 2006, and moved into Dickey-Stephens Park in nearby North Little Rock in April 2007.

The Little Rock Rangers soccer club of the National Premier Soccer League played their inaugural seasons in 2016 & 2017 for the men's and women's teams respectively. Home games are played at War Memorial Stadium.

Little Rock was also home to the Arkansas Twisters (later Arkansas Diamonds) of Arena Football 2 and Indoor Football League and the Arkansas RimRockers of the American Basketball Association and NBA Development League. Both of these teams played at Verizon Arena in North Little Rock.

The city is also home to the Little Rock Trojans, the athletic program of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. The majority of the school's athletic teams are housed in the Jack Stephens Center, which opened in 2005. The Trojans play in the Sun Belt Conference, where the Arkansas State Red Wolves are their chief rival.

Little Rock's War Memorial Stadium plays host to at least one University of Arkansas Razorback football game each year. The stadium is known for being in the middle of a golf course. Each fall, the city closes the golf course on Razorback football weekends for fans to tailgate. It is estimated that over 80,000 people are present for the tailgating activities on these weekends. War Memorial also hosts the Arkansas High School football state championships, and starting in the fall of 2006 hosts one game apiece for the University of Central Arkansas and the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. Arkansas State University also plays at the stadium from time to time.

Little Rock was a host of the First and Second Rounds of the 2008 NCAA Men's Basketball Tournament. It has also been a host of the SEC Women's Basketball Tournament.

The now defunct Arkansas RiverBlades and Arkansas GlacierCats, both minor-league hockey teams, were located in the Little Rock area. The GlacierCats of the now defunct Western Professional Hockey League (WPHL) played in Little Rock at Barton Coliseum while the RiverBlades of the ECHL played at the Verizon Arena.

Little Rock is home to the Grande Maumelle Sailing Club. Established in 1959, the club hosts multiple regattas during the year on both Lake Maumelle and the Arkansas River.

Little Rock is also home to the Little Rock Marathon, held on the first Saturday of March every year since 2003. The marathon features the world's largest medal given to marathon participants.

Media

Print

The Arkansas Democrat Gazette is the largest newspaper in the city, as well as the state. As of March 31, 2006, Sunday circulation is 275,991 copies, while daily (Monday-Saturday) circulation is 180,662, according to the Audit Bureau of Circulations. The monthly magazine Arkansas Life is part of the newspaper's niche publications division, and began publication in September 2008. From 2007 to 2015, the newspaper also published the free tabloid Sync Weekly. Beginning in 2020, the ADG ceased weekday publication of the newspaper and moved to an exclusive online version. The only physical newspaper that the Democrat-Gazette now publishes is a Sunday edition.[29]

Daily legal and real estate news is also provided Monday through Friday in the Daily Record. Healthcare news covered by Healthcare Journal of Little Rock. Entertainment and political coverage is provided weekly in Arkansas Times. Business and economics news is published weekly in Arkansas Business. Entertainment, Political, Business, and Economics news is published Monthly in "Arkansas Talks" www.Arkansastalks.org

In addition to area newspapers, the Little Rock market is served by a variety of magazines covering diverse interests. The publications are:

- At Home in Arkansas

- AY Magazine

- Inviting Arkansas

- Little Rock Family

- Little Rock Soiree

- RealLIVING

Television

Many television networks have local affiliates in Little Rock, in addition to numerous independent stations. As for cable TV services, Comcast has a monopoly over Little Rock and much of Pulaski County. Some suburbs have the option of having Comcast, Charter or other cable companies.

Television stations in the Little Rock area include:

| Call letters | Number | Network |

|---|---|---|

| KETS/AETN | 2 | PBS |

| KETS-2 | 2.2 | Create Arkansas Information Reading Service (audio only, only on SAP; radio reading service) |

| KETS-3 | 2.3 | PBS Kids |

| KETS-4 | 2.4 | World |

| KARK | 4 | NBC |

| Laff | 4.2 | Laff |

| Grit | 4.3 | Grit |

| Antenna TV | 4.4 | Antenna TV |

| KATV | 7 | ABC |

| KATV-DT2 | 7.2 | Comet TV |

| Charge! | 7.3 | Charge! |

| TBD | 7.4 | TBD |

| KTHV | 11 | CBS |

| THV2 | 11.2 | Court TV |

| Justice | 11.3 | Justice Network |

| Quest | 11.4 | Quest (U.S. TV network) |

| Circle | 11.5 | Circle (TV network) |

| KLRT | 16 | Fox |

| 16.2 | Escape | |

| KVTN | 25 | VTN: Your Arkansas Christian Connection |

| KASN | 38 | The CW |

| KKAP | 36 | Daystar |

| KARZ | 42 | MyNetworkTV |

| 42.2 | Bounce TV | |

| 42.3 | Ion Television | |

| KMYA-DT | 49.1 | Me-TV |

Infrastructure

Healthcare

Hospitals in Little Rock include:

- Arkansas State Hospital – Psychiatric Division

- Arkansas Children's Hospital

- Arkansas Heart Hospital

- Baptist Health Medical Center

- Central Arkansas Veteran's Health care System (CAVHS)

- Pinnacle Pointe Hospital

- St. Vincent Health System

- UAMS Medical Center

List of highways

Little Rock is served by two primary Interstate Highways and four auxiliary Interstates. Interstate 40 (I-40) passes through North Little Rock to the north, and I-30 enters the city from the south, terminating at I-40 in the north of the Arkansas River. Shorter routes designed to accommodate the flow of urban traffic across town include I-430, which bypasses the city to the west, I-440, which serves the eastern part of Little Rock including Clinton National Airport, and I-630 which runs east–west through the city, connecting west Little Rock with the central business district. I-530 runs southeast to Pine Bluff as a spur route.[30]

U.S. Route 70 (US 70 parallels I-40 into North Little Rock before multiplexing with I-30 at the Broadway exit (exit 141B). US 67 and US 167 share the same route from the northeast before splitting. US 67 and US 70 multiplex with I-30 to the southwest. US 167 multiplexes with US 65 and I-530 to the southeast.

Rail

Amtrak serves the city twice daily via the Texas Eagle, with northbound service to Chicago and southbound service to San Antonio, as well as numerous intermediate points. Through service to Los Angeles and intermediate points operates three times a week. The train carries coaches, a sleeping car, a dining car, and a Sightseer Lounge car. Reservations are required.

Aviation

Seven airlines serve 14 national/international gateway cities, e.g. Atlanta, Dallas, Chicago, Charlotte, Orlando etc. from Clinton National Airport. In 2006 they carried approximately 2.1 million passengers on approximately 116 daily flights to and from Little Rock. In July 2017, a seventh airline, Frontier Airlines, announced that they would be resuming scheduled operations to Denver in 2018.

Bus

Greyhound Lines serves Dallas and Memphis, as well as intermediate points, with numerous connections to other cities and towns. Jefferson Lines serves Fort Smith, Kansas City, and Oklahoma City, as well as intermediate points, with numerous connections to other cities and towns. These carriers operate out of the North Little Rock bus station.

Public transportation

Within the city, public bus service is provided by the Rock Region Metro, which until 2015 was named the Central Arkansas Transit Authority (CATA). As of January 2010, CATA operated 23 regular fixed routes, 3 express routes, as well as special events shuttle buses and paratransit service for disabled persons. Of the 23 fixed-route services, 16 offer daily service, 6 offer weekday service with limited service on Saturday, and one route runs exclusively on weekdays. The three express routes run on weekday mornings and afternoons. Since November 2004, downtown areas of Little Rock and North Little Rock have been additionally served by the Metro Streetcar system (formerly the River Rail Electric Streetcar), also operated by Rock Region Metro. The Streetcar is a 3.4-mile (5.5 km)-long heritage streetcar system that runs from the North Little Rock City Hall and throughout downtown Little Rock before crossing over to the William J. Clinton Presidential Library. The streetcar line has fourteen stops and a fleet of five cars with a daily ridership of around 350.

Modal characteristics

According to the 2016 American Community Survey, 82.9 percent of working Little Rock residents commuted by driving alone, 8.9 percent carpooled, 1.1 percent used public transportation, and 1.8 percent walked. About 1.3 percent commuted by all other means of transportation, including taxi, bicycle, and motorcycle. About 4 percent worked out of the home.[31]

In 2015, 8.2 percent of city of Little Rock households were without a car, which increased slightly to 8.9 percent in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Little Rock averaged 1.58 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8 per household.[32]

Notable people

- Matt Besser (born 1967), improvisational comedian and Upright Citizens Brigade co-founder

- Bobo Brazil (1924–1998), African-American professional wrestler, from Little Rock

- Kevin Brockmeier (born 1972), author of fantasy and literary fiction

- Bill Clinton (born 1946), former President of the United States and former governor of the state, lived in the city

- Hillary Clinton (born 1947), politician

- Chelsea Clinton (born 1980), daughter of Bill and Hillary Clinton, born in Little Rock

- Danielle Evans (born 1985), model, winner of Cycle 6 of "America's Next Top Model"

- John Gould Fletcher (1886–1950), Pulitzer Prize-winning Imagist poet and author, was born in Little Rock. The Fletcher Branch Library of the Central Arkansas Library System is named after him.[33]

- Will Hastings (born 1996), football player for the New England Patriots, born and raised in Little Rock, Pulaski Academy graduate

- Amy Lee (born 1981) lead vocalist of rock/metal band Evanescence, attended high school in Little Rock

- The Little Rock Nine, group of nine African American students who were initially prevented by the state government from entering a racially segregated school in 1957.

- Douglas MacArthur (1880–1964), U.S. general, born in Little Rock

- James Smith McDonnell, aviation pioneer and founder of McDonnell Aircraft Corporation.

- Sanford N. McDonnell, engineer, businessman and philanthropist; former chairman and CEO of McDonnell Douglas

- Darren McFadden, football player for the Dallas Cowboys, born in Little Rock

- Kyle Milliken (born 1989), computer hacker and email spammer responsible for breaching Imgur, Kickstarter and Quora

- Charlotte Moorman (1933–1991), cellist and advocate for avant-garde music, born in Little Rock

- Willie Oates (1918–2008), philanthropist, social activist, and politician, died in Little Rock

- Ben Piazza (1933 – 1991), American actor.

- Florence Price (born 1887), classical composer

- Brooks Robinson (born 1937), Hall of Fame third baseman for the Baltimore Orioles

- Winthrop Rockefeller (1912–1973), businessman, philanthropist, the first Republican governor of Arkansas since Reconstruction and the grandson of John D. Rockefeller.

- Pharoah Sanders (born October 13, 1940), jazz saxophonist, born in Little Rock

- Sheryl Underwood (born 1963), Emmy-winning co-host of The Talk, stand-up comedian, and actress, born in Little Rock

- Sam Walton (1918–1992), businessman and entrepreneur, died in Little Rock

Sister cities

Friendship cities

Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear, United Kingdom – 1999

Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear, United Kingdom – 1999 La Petite-Pierre, Bas-Rhin, France (Emeritus)[34]

La Petite-Pierre, Bas-Rhin, France (Emeritus)[34]

See also

Notes

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- Official records for Little Rock began on 28 February 1875 at the State Capitol and maintained there until 30 April 1942. The next day, and until 7 August 1942, temperature and precipitation were recorded separately at two different locations in and around Little Rock, and the official climatology station has been Adams Field since 8 August 1942. For more information, see Threadex

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- "Census shows overall state population up 9.1 percent". Arkansasonline.com. February 10, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "Our Historical City". City of Little Rock. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- "Colorful Names". Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism. Archived from the original on November 24, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2014.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- "The Hyde Park Historical Record". Hyde Park Historical Society. December 29, 2017 – via Google Books.

- Williams, C. Fred (December 29, 2017). Historic Little Rock: An Illustrated History. HPN Books. ISBN 9781893619821 – via Google Books.

- Herndon, Dallas Tabor (1922). The High Lights of Arkansas History. Arkansas History commission. p. 37 – via Internet Archive.

arkopolis little rock.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- Bradbury, Cary (November 14, 2007). "North Little Rock (Pulaski County)". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- Clinton, Bill (2004). My Life. Knopf Publishing Group. p. 244.

- "Climate Statistics for the Little Rock Area" (PDF). National Weather Service North Little Rock. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 1, 2011. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- "Station Name: AR LITTLE ROCK AP ADAMS FLD". National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- "NOAA". NOAA.

- "Monthly Averages for Little Rock, AR (72201)". The Weather Channel. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Arkansas – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- Prodis, Julia (October 1, 1995). "Little Rock's Boyz in the Hood Illustrate '90s American Graffiti : Violence: Gangs have colonized even small cities, bringing big-city crime with them. Lifestyle wins adherents via television". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- Eckholm, Erik (January 31, 1993). "Teen-Age Gangs Are Inflicting Lethal Violence on Small Cities". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- Koon, David; Herron, Kaya (July 15, 2015). "Bangin' in the '90s: An oral history: Police, former gang members, city leaders look back at Little Rock's gang wars". Arkansas Times. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- "Little Rock Branch | Regional Executive Robert Hopkins". St. Louis Fed. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- "arkansassymphony.org". arkansassymphony.org. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- "The 12 Best Places to Live in 2019". Outsideonline.com. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- Hargett, Malea (May 12, 2012). "State's last black Catholic school to close". Arkansas Catholic. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- Hargett, Malea (March 28, 2013). "Despite 'year of grace,' St. Joseph School will close". Arkansas Catholic. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- Tugman, Lindsey (March 11, 2014). "10 more unsolved Arkansas mysteries". KTHV. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- "Sync weekly magazine to cease publication Wednesday". Arkansas Online. October 23, 2015. Archived from the original on November 27, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- General Highway Map, Pulaski County, Arkansas (PDF) (Map). 1:62500. Cartography by Planning and Research Department. Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department. December 22, 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- "Means of Transportation to Work by Age". Census Reporter. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "Car Ownership in U.S. Cities Data and Map". Governing. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "John Gould Fletcher". The Central Arkansas Library System. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- "Boards and Commissions City of Little Rock". littlerock.org. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- "Caxias do Sul, Brazil". City of Little Rock. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- "Navy Names Littoral Combat Ship Little Rock" Archived February 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine DOD press release. 15 July 2011

Further reading

- The Atlas of Arkansas, Richard M. Smith 1989

- Cities in the U.S.; The South, Fourth Edition, Volume 1, Linda Schmittroth, 2001

- Greater Little Rock: a contemporary portrait, Letha Mills, 1990

- How We Lived: Little Rock as an American City, Frederick Hampton Roy, 1985

- Morgan, James. "Little Rock: The 2005 American Heritage Great American Place" American Heritage, October 2005.

- O'Donnell, William W. (1987). The Civil War Quadrennium: A Narrative History of Day-to-Day Life in Little Rock, Arkansas During the American War Between Northern and Southern States 1861-1865 (2nd ed.). Little Rock, Ark.: Civil War Round Table of Arkansas. LCCN 85-72643 – via Horton Brothers Printing Company.

- Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940-1970, John A. Kirk, 2002.

External links

- Government

- General information

Geographic data related to Little Rock, Arkansas at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Little Rock, Arkansas at OpenStreetMap- Little Rock, Arkansas at City-Data.com

- Little Rock, Arkansas at TripSavvy (tripsavvy.com)

- Little Rock, Arkansas at Encyclopedia of Arkansas

- Works by or about Little Rock, Arkansas at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Little Rock, Arkansas in libraries (WorldCat catalog)