1860 Democratic National Conventions

The 1860 Democratic National Conventions were a series of presidential nominating conventions held to nominate the Democratic Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1860 election. The first convention, held from April 23 to May 3 in Charleston, South Carolina, failed to nominate a ticket, while two subsequent conventions, both held in Baltimore, Maryland in June, nominated two separate presidential tickets.

| 1860 presidential election | |

| Conventions | |

|---|---|

| Date(s) | April 23–May 3, 1860 & June 18–23, 1860 |

| City | Charleston, South Carolina & Baltimore, Maryland |

| Venue | South Carolina Institute Hall, Front Street Theater & Maryland Institute (Southern) |

| Candidates | |

| Presidential nominee | Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois (Official) John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky (Southern) |

| Vice presidential nominee | Herschel V. Johnson of Georgia (Official) Joseph Lane of Oregon (Southern) |

Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois entered the Charleston convention as the front-runner for the presidential nomination, and while he won a majority on the first presidential ballot of the convention, the convention rules required a two-thirds majority to win the nomination, with Douglas's adherence to the Freeport Doctrine regarding slavery in the territories engendering strong opposition from many Southern delegates: opponents of Douglas's nomination spread their support among five major candidates, including former Treasury Secretary James Guthrie of Kentucky and Senator Robert M. T. Hunter of Virginia. After 57 ballots over 10 days, in which Douglas consistently won a majority but failed to reach the two-thirds required, the Charleston convention adjourned.

The Democratic convention reconvened in Baltimore on June 18, but many Southern delegates either boycotted the convention or walked out in protest after the convention adopted a platform in which it pledged to abide by the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States upon questions of Constitutional Law regarding slavery.[1] While Douglas was nominated for president on the second ballot (the 59th ballot overall), Senator Benjamin Fitzpatrick of Alabama was nominated for vice president, but he refused the nomination: he was replaced by former Governor Herschel Vespasian Johnson of Georgia.

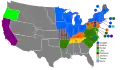

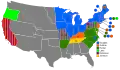

The boycotting Southern Democrats and those who had walked out held their own separate convention and adopted a pro-slavery platform, nominating Vice President John C. Breckinridge for president, and Senator Joseph Lane of Oregon for vice president. While Douglas and Breckinridge received a combined 47.62% of the popular vote in the 1860 presidential election, they lost the election to Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln.

Charleston convention

.jpg.webp)

The 1860 Democratic National Convention convened at South Carolina Institute Hall (destroyed in the Great Fire of 1861) in Charleston, South Carolina on 23 April 1860. Since Charleston was the most pro-slavery city in the U.S. at the time, the galleries at the convention were packed with pro-slavery spectators.[2]

The front-runner for the nomination was Douglas, who was considered a moderate on the slavery issue. With the 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act, he advanced the doctrine of popular sovereignty: allowing settlers in each Territory to decide for themselves whether slavery would be allowed – a change from the flat prohibition of slavery in most Territories under the Missouri Compromise, which the South had welcomed. However, the Supreme Court’s ensuing 1857 Dred Scott decision declared that the Constitution protected slavery in all Territories.

Douglas was challenged for his Senate seat by Abraham Lincoln in 1858, and narrowly won re-election by professing the Freeport Doctrine, a de facto rejection of Dred Scott, with militant Southern "Fire-Eaters", such as William Yancey of Alabama, opposing him as a traitor. Many of them openly predicted a split in the party and the election of Republican front-runner William H. Seward.[2]

Urged by Yancey, the delegations from seven Deep South states (Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas, and Florida) met in a separate caucus before the convention. They reached a tentative consensus to "stop Douglas" by imposing a pro-slavery party platform which he could not run on if nominated.[3]

The "Fire-eater" majority on the convention's platform committee, chaired by William Waightstill Avery of North Carolina, produced an explicitly pro-slavery document, endorsing Dred Scott and Congressional legislation protecting slavery in the territories. Northern Democrats refused to acquiesce, as Dred Scott was extremely unpopular in the North, and the Northerners said they could not carry a single state with that platform, which in turn would effectively end their hopes of retaining control of the White House, as no candidate until that point had won the presidency without winning at least one of New York or Pennsylvania, and only four presidents overall (John Adams in 1796, James Madison in 1812, John Quincy Adams in 1824, and James Buchanan in 1856) had been elected without winning both.

On 30 April, the convention (by a vote of 165 to 138) adopted the minority (Northern) platform, which omitted these planks, and 50 Southern delegates walked out of the convention in protest:[2] the entire Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas delegations, three of the four delegates from Arkansas, and one of the three delegates from Delaware.

These delegates gathered at St. Andrews Hall on Broad Street and declared themselves the real convention as the Institute Hall convention proceeded to nominations. The dominant Douglas forces believed their path was now clear.[2]

Six major candidates were nominated at the convention: Douglas, former Treasury Secretary James Guthrie of Kentucky, Senator Robert M. T. Hunter of Virginia, Senator Joseph Lane of Oregon, former Senator Daniel S. Dickinson of New York, and Senator Andrew Johnson of Tennessee.

While Douglas led on the first ballot, receiving 145½ of 253 votes cast, convention rules at the time required a two-thirds vote to win the nomination. Further to this, convention chairman Caleb Cushing further ruled that this was two-thirds of the whole membership, not just two-thirds of those present and voting.

This ruling meant Douglas needed 202 votes (or 56½ more votes), or 80% of the remaining 253 delegates, and also would have required several of the remaining Southern delegates to vote for Douglas, who they vehemently opposed.

Consequently, the convention held 57 ballots, and though Douglas led on all of them, he never received more than 152½ votes. On the 57th ballot, Douglas received 151½ votes, still 50½ votes short of the nomination, though far ahead of Guthrie, who was second with 65½. On 3 May, the delegates voted to adjourn the convention, and reconvene in Baltimore six weeks later.

Candidates receiving votes for president at the Charleston convention:

Presidential candidates

Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois

Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois Former Secretary of the Treasury James Guthrie of Kentucky

Former Secretary of the Treasury James Guthrie of Kentucky Senator Robert M. T. Hunter of Virginia

Senator Robert M. T. Hunter of Virginia Senator Joseph Lane of Oregon

Senator Joseph Lane of Oregon Former Senator Daniel S. Dickinson of New York

Former Senator Daniel S. Dickinson of New York Senator Andrew Johnson of Tennessee

Senator Andrew Johnson of Tennessee

A few votes went to former Senator Isaac Toucey of Connecticut and Senator James Pearce of Maryland, while Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi (the future Confederate President), who received one vote on over fifty ballots from Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts. Ironically, during the Civil War, Butler became a Union general, and Davis ordered him hanged as a criminal if ever captured.

| Charleston presidential ballot | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ballot | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th | 13th | 14th | 15th | 16th | 17th | 18th | 19th | 20th | 21st | 22nd | 23rd | 24th | 25th | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Douglas | 145.5 | 147 | 148.5 | 149 | 149.5 | 149.5 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 149.5 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 152.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | ||||

| Guthrie | 35.5 | 36.5 | 42 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 39.5 | 38.5 | 38.5 | 41 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 41 | 41.5 | 42 | 42 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 42 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 41.5 | ||||

| Hunter | 42 | 41.5 | 36 | 41.5 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 40.5 | 39.5 | 39 | 38 | 38 | 28.5 | 27 | 26.5 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 35 | ||||

| Lane | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 20 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 19.5 | 19.5 | 9.5 | ||||

| Dickinson | 7 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4.5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | ||||

| Johnson | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | ||||

| Toucey | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Davis | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Pearce | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Charleston presidential ballot | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ballot | 26th | 27th | 28th | 29th | 30th | 31st | 32nd | 33rd | 34th | 35th | 36th | 37th | 38th | 39th | 40th | 41st | 42nd | 43rd | 44th | 45th | 46th | 47th | 48th | 49th | 50th | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Douglas | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 152.5 | 152.5 | 152.5 | 152 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | ||||

| Guthrie | 41.5 | 42.5 | 42 | 42 | 45 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 48 | 64.5 | 66 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | ||||

| Hunter | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 32.5 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 22 | 22 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | ||||

| Lane | 9 | 8 | 8 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 12.5 | 13 | 13 | 12.5 | 13 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | ||||

| Dickinson | 12 | 12 | 12.5 | 13 | 13 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Johnson | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Davis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Charleston presidential ballot | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ballot | 51st | 52nd | 53rd | 54th | 55th | 56th | 57th | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Douglas | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Guthrie | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 61 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hunter | 16 | 16 | 16 | 20.5 | 16 | 16 | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lane | 14 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dickinson | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Davis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

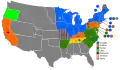

1st presidential ballot

2nd presidential ballot

3rd presidential ballot

4th presidential ballot

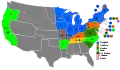

5th presidential ballot

6th presidential ballot

7th presidential ballot

8th presidential ballot

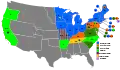

9th presidential ballot

10th presidential ballot

11th presidential ballot

12th presidential ballot

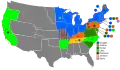

13th presidential ballot

14th presidential ballot

15th presidential ballot

16th presidential ballot

17th presidential ballot

18th presidential ballot

Baltimore convention

The Democrats re-convened at the Front Street Theater (destroyed in the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904) in Baltimore, Maryland on 18 June. The resumed convention's first business was to decide whether to re-admit the delegates who had walked out of the Charleston session, or to seat replacement delegates who had been named by pro-Douglas Democrats in some states: other delegates had boycotted the Baltimore convention.

The credentials committee's majority report recommended re-admitting all delegates except those from Louisiana and Alabama, while the minority report recommended re-admitting some of the Louisiana and Alabama delegates as well. After the committee's majority report was adopted 150-100½, and new Louisiana and Alabama delegates were seated, 56 delegates - most of those remaining from the South, and a scattering of delegates from northern and far western states - all walked out of the convention in protest.[4]

Presidential balloting

The following received votes at this convention:

Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois

Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois Former Secretary of the Treasury James Guthrie of Kentucky

Former Secretary of the Treasury James Guthrie of Kentucky Former Senator Daniel S. Dickinson of New York

Former Senator Daniel S. Dickinson of New York Former Governor Horatio Seymour of New York

Former Governor Horatio Seymour of New York

After the convention resumed voting on a nominee, Douglas received 173½ of 190½ votes cast on the first ballot (the 58th overall), and 181½ votes of 194½ votes cast on the second ballot (the 59th overall).

After a rollcall following the second ballot, it was realized that there were only 194½ delegates present, meaning there were insufficient delegates for Douglas to receive 202 votes as per Cushing's earlier ruling.

After the delegates unanimously voted to rescind this, it was declared by acclamation that Douglas had received the required two-thirds of the votes cast, and was therefore nominated.

| Baltimore presidential ballot | ||||

| Ballot | 1st | 2nd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Douglas | 173.5 | 181.5 | ||

| Guthrie | 9 | 5.5 | ||

| Breckinridge | 5 | 7.5 | ||

| Horatio Seymour | 1 | 0 | ||

| Thomas S. Bocock | 1 | 0 | ||

| Dickinson | 0.5 | 0 | ||

| Henry A. Wise | 0.5 | 0 | ||

Vice-Presidential balloting

Senator Benjamin Fitzpatrick of Alabama was the only candidate for the Vice Presidential nomination: William C. Alexander of New Jersey was withdrawn when it was mentioned he would not allow his name to be presented as a candidate.

While Fitzpatrick received 198½ votes, he later refused the nomination, something that has only happened thrice (the other occasions were in 1844 and 1924).

Senator Benjamin Fitzpatrick of Alabama

Senator Benjamin Fitzpatrick of Alabama

| Vice presidential ballot | ||||

| 1st | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitzpatrick | 198.5 | |||

| Blank | 1 | |||

Since the Conventions concluded with no vice-presidential candidate being nominated, Douglas offered the nomination to former Senator and Governor Herschel V. Johnson of Georgia,[4] which Johnson accepted.

Former Governor Herschel V. Johnson of Georgia

Former Governor Herschel V. Johnson of Georgia

“Breckinridge Democrats” convention

The Southern Democrats who had walked out of or boycotted the convention, with their allies, reconvened at the Maryland Institute in Baltimore. This rival convention adopted a radical pro-slavery platform, and nominated Breckinridge for president.

John C. Breckinridge for President

John C. Breckinridge for President Joseph Lane for vice president

Joseph Lane for vice president

| "Breckinridge Democrats" presidential ballot | ||||

| Ballot | 1st | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breckinridge | 81 | |||

| Dickinson | 24 | |||

Lane was nominated for vice president by acclamation.

Consequences

After the break-up of the Charleston convention, many of those present stated that the Republicans were now certain to win the 1860 Presidential election.[2]

In the general election, the actual division in Democratic popular votes did not directly affect any state outcomes except California, Oregon, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia. Of these states, only California and Oregon were free states, and although both were carried by Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln they combined for only seven of Lincoln’s 180 electoral votes. The latter three states were slave states that were carried by neither Douglas, Breckinridge nor Lincoln but by John Bell, nominee of the Constitutional Union Party. Composed mainly of former Whigs and Know-Nothings, the Constitutional Union Party attempted to ignore the slavery issue in favor of preserving the Union.

Even if California, Oregon and every state carried by Douglas, Breckinridge or Bell had been carried by a single Presidential nominee, Lincoln would still have had a large majority of electoral votes.[4] However, the split in the Democratic Party organization was a serious handicap in many states, especially Pennsylvania, and almost certainly reduced the aggregate Democratic popular vote. Pennsylvania’s 27 electoral votes were especially decisive in ensuring a Republican victory – had Lincoln failed to carry that state combined with any other free state, he could not have obtained a majority of electoral votes, forcing a contingent election in the House of Representatives.

James M. McPherson suggested in Battle Cry of Freedom that the “Fire-eater” program of breaking up the convention and running a rival ticket was deliberately intended to bring about the election of a Republican as President, and thus trigger secession declarations by the slave-owning states. Whatever the “intent” of the fire-eaters may have been, doubtless many of them favored secession, and the logical, probable, and actual consequence of their actions was to fragment the Democratic party and thereby virtually ensure a Republican victory.[5]

See also

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- U.S. presidential nomination convention

- List of Democratic National Conventions

- 1860 Republican National Convention

- 1860 United States presidential election

References

- "Democratic Party Platform; June 18, 1860". avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Catton, Bruce (1961). The Coming Fury. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., Inc. pp. 37–40.

- Heidler, David S. Pulling the Temple Down: The Fire-Eaters and the Destruction of the Union ISBN 0-8117-0634-6, p. 149. Jefferson Davis, a relative moderate, saw this coalition of the Deep South with Douglas's enemies in the Buchanan administration as potentially dangerous, and called for abandoning a platform as the Whigs had in 1840, just settling on an agreed-to candidate. The moderates, principally found in Alabama and Georgia, were outvoted in caucus.

- Congressional Quarterly's Guide to U.S. Elections. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, Inc. 1985. pp. 45–46, 169. ISBN 0-87187-339-7.

- Davis, Jefferson. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government pp. 43-46

- Official proceedings of the Democratic national convention, held in 1860, at Charleston and Baltimore

- Proceedings of the conventions at Charleston and Baltimore. Published by order of the National Democratic Convention assembled in Maryland Institute, Baltimore, and under the supervision of the National Democratic Executive Committee. (Breckinridge Faction)

External links

- Democratic Party Platform of 1860 at The American Presidency Project

- Democratic Party Platform (Breckinridge Faction) of 1860

| Preceded by 1856 Cincinnati, Ohio |

Democratic National Conventions | Succeeded by 1864 Chicago, Illinois |