Đurađ Branković

Đurađ Branković (pronounced [d͡ʑûrad͡ʑ brǎːŋko̞ʋit͡ɕ]; Serbian Cyrillic: Ђурађ Бранковић; Hungarian: Brankovics György; 1377 – 24 December 1456) was the Serbian Despot from 1427 to 1456. He was one of the last Serbian medieval rulers. He was a participant in the battle of Ankara (1402) and Ottoman Interregnum (1403-1413). During his reign, the despotate was a vassal of both, Ottoman sultans as well as Hungarian kings. Despot George was neutral during the Polish-Lithuanian (1444) and Hungarian-Wallachian (1448) crusades. In 1455, he was wounded and imprisoned during clashes with the Hungarians, after which the young Sultan Mehmed II launched the Siege of Belgrade and its large Hungarian garrison. Despot Đurađ died at the end of 1456, due to complications stemming from the wound. After his death, Serbia, Bosnia and Albania (West Balkans) became practically annexed by sultan Mehmed II, which only ended after centuries of additional conquests of Byzantine lands. Đurađ attained a large library of Serbian, Slavonic, Latin, and Greek manuscripts. He made his capital Smederevo a centre of Serbian culture. He was the first of the Branković dynasty to hold the Serbian monarchy.

| Đurađ Branković | |

|---|---|

| Despot of the Kingdom of Rascia | |

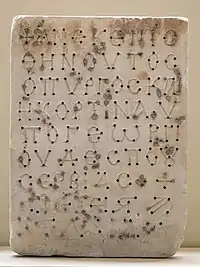

.jpg.webp) Portrait from The Esphigmen Charter of despot Đurađ Branković, issued to the monastery of Esphigmen on Athos in 1429 | |

| Reign | 1427—1456 |

| Predecessor | Stefan Lazarević |

| Successor | Lazar Branković |

| Born | 1377 |

| Died | 24 December 1456 (aged 78–79) |

| Spouse | Eirene Kantakouzene |

| Issue | Todor Branković Grgur Branković Mara Branković Stefan Branković Katarina, Countess of Celje Lazar Branković |

| House | Branković |

| Father | Vuk Branković |

| Mother | Mara |

Early life

He was the son of lord Vuk Branković and Mara, the daughter of Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović. His wife, Eirene Kantakouzene, a granddaughter of Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos, was a Byzantine princess. Her brother Thomas was the commander of Smederevo.

Despot Stefan had appropriated for himself properties that were part of the hereditary lands of Vuk, which resulted in Vuk joining the opposition. Vuk entered a pact with the Ottomans when Stefan had left Ottoman service and joined Hungary, fueling the domestic conflict between the two cousins; Vuk befriended Musa, only for revenge. The conflict went on for 10 years. Once reconciled, Stefan tried to make the most benefit of Đurađ, Vuk's son. Being childless, despot Stefan Lazarević made Đurađ his heir. When Đurađ succeeded Stefan, he was mature with rich experience, aged 50 in 1427.[1]

Between Two Worlds

Despot of Serbia

At the time of the despot Stefan's death, George Brankovic was in Zeta (Montenegro), and Hungarian King Sigismund was in Wallachia. When they heard of the despot's death, they both headed to Belgrade Fortress. Negotiations around Belgrade lasted during September and October 1427. The surrender of the city was a condition that the Hungarian king to recognize George Brankovic as the new Serbian ruler. The State Assembly headed by Mr. George and Serbian Patriarch Nikanon decided to leave Belgrade to the Hungarians. King Sigismund planned for Belgrade and Golubac to be included in the new Hungarian defense system at the Danube frontier, which was based on border fortresses. Serbian duke Jeremiah of Golubac Fortress who was refus to recognased George as the new ruler, entered into negotiations with the Hungarian King Sigismund. He asked him for 12,000 ducats, which he allegedly gave to the late despot Stefan to own the city and as evidence, Jeremiah submitted a despot's letter, demanding that Sigismund pay him the said sum if he wanted Golubac. King Sigismund challenged the authenticity of the seal and the entire despot's letter, which Jeremiah submitted as evidence, refused to pay the claimed sum, and in late autumn, in December 1427, Jeremiah ceded the city to the Ottomans under the same conditions. The loss of Golubac was a major blow to King Sigismund as the Turks gained an important fortification on the Danube. King Sigismund decided to conquer the Golubac. In the early spring of 1428 he assembled an army and began a siege. Meanwhile, Sultan Murad II arrived with the army, who are in the battle defeating King Sigismund. After the Ottoman victory, George Brankovic and Duke of Wallachia Dan II recognized the sultan's suzerainty and according to an agreement they start to pay tribute.

Since the Hungarians took over Belgrade and the Turks Golubac, despot George decided to build a new fortress and capital on the right bank of the Danube. The new Serbian capital Smederevo is planned to be located at the same distance between Hungarian Belgrade and Turkish Golubac and to separated them. Town was building gradually with great material and human renunciation. In the period from 1428 to 1430 a small town was built and a despot's court was housed there (curia domini despoti). Then the Great Town was built to protect the city settlement that developed along the despot's court. In the Great Town, addition to town houses there were churches, shops, warehouses, a shelter for the surrounding population. The works were led by the Romey Greeks brothers George and Thomas Kantakouzenos who for the project hired many Greek masons. In the summer of 1429, The Romey Emperor John VIII Palaiologos sent to George Philanthropenos with the task of crowning George Brankovic as the despot of Rascia (Serbia).

On May 31, 1433, King Sigismund was crowned at church of St. Peter in Old Rome for Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. On April 20, 1434, George Branković's youngest daughter Katarina and Ulrich II of Celje were wed in the new fortress. This marriage stressed the friendly relations the Despot had with the Ottoman Porte, although Ulrich's kinship with the Queen of Hungary implied an increased Serbo-Hungarian alliance. As a result, Vizier Mehmet Saridže-pasha arrived in Smederevo in mid-1434 with a message from Sultan court of Edirne. It stated that Serbia's safety from the Ottoman Empire could only be guaranteed through the marriage of Branković's older daughter to Sultan Murad II. After much deliberation, the council convoked at the palace conceded, and arrangements were made for Mara to be engaged to the Sultan. That autumn, Murad sent several of his "most famous viziers" to retrieve his fiancée. Despot George was in a complex situation, King Sigismund thought he was Turkish and Sultan Murad II that he was a Hungarian marionette.

On August 14, 1435, a formal contract of "brotherhood and friendship" between Serbia and the Republic of Venice was signed in Smederevo's audience hall

Sultan Murad II heard that the Great Christian Coalition in Europa was preparing against the Turks. He was informed that a Serbian despot would join this coalition. In fact, there was Great Council of Christendom in Florence. Despot George sent envoys to Sultan Murad II who claimed that he was not breaking their agreement and becoming pro-Hungarian. Anyway, Sultan Murad II decided to prevent it and conquer Serbia. In 1439, Sultan's army was sent to Serbia because Murad II decided to conquer as soon possible new Smederevo, Novo Brdo, and perhaps Hungarian Belgrade itself. According to sources, he raised an army of 200,000 men (but the most realistic number is 60–70,000 men) and all ships on the great rivers. He sent one army to Novo Brdo, and with the other, the main one, which numbered about 130,000 men (probably 30,000 men), in late April or early May 1439 began the siege of Smederevo. After three months of siege, in early August 1439 Smederevo fell. In Fact, defenders led by despot's son Grgur Brankovic and Thomas Kantakouzenos are remaining without food after which they decide to open the town's gates to Muslims and in that way prevent robbery and massacre. Meanwhile, the despot George went to exile on the camp of the Hungarian king Albert II. On the news of the fall of Serbia under Islam a fear was spread in Hungary. In the swampy part of the Danube frontier near Belgrade, King Albert fell ill of dysentery in September 1439. He died next month on the way to Vienna. Albert's death initiated a Hungarian Civil War, which lasted for twenty years (1439–1458) and ended only with the arrival of Matthias Corvinus on the Hungarian throne. In December 1439, as Hungarian magnate despot George was nominated his son Lazar for marriage to Elizabeth, who wanted to preserve the throne but was rejected because he was schismatic. The more serious candidate was King of Poland Władysław III of the Lithuanian Dynasty of the Jegiellonian. At the beginning of 1440, Elizabeth gave her consent to the marriage with the young Władysław. Marriage with him would bring an alliance with Poland and an end to the conflict against Hungary (because it was known that Murad's deputies were in Poland who offered an alliance against Hungary). Meanwhile, in February 1440, Elizabeth gave birth to a son Ladislaus the Posthumous and then changed her mind about marrying with Władysław. In May 1440, the newborn baby is crowned with a stolen crown for the king. Then Elizabeth and her son took refuge to the German King Frederick III in Vienna. In the party that supported Ladislaus for the king, as the grandson of King Sigismund, they were George Brankovic, Nicholas of Ilok, Ladislaus Garai, Frederick II and Ulrich II of Celje. On the eve of the arrival of Władysław, despot George decided to leave Hungary. Despot George was offended that he, and especially his son Lazar, had missed the royal crown.

The Ottoman sultan reacted to the throne change, and the Hungarian influence which was felt more than he could afford, with sending an army into Serbia, which conquered Niš, Kruševac and besieged Novo Brdo. As to secure his prestige in Serbia, which had been weakened due to him, King Sigismund sent Despot Đurađ his own army. The combined army destroyed a large Ottoman detachment near Ravanica, for which effort the king on 19 November 1427 thanked especially Nicholas Bocskay. Another Ottoman detachment attacked neighbouring Serbian and Hungarian places from Golubac, especially the Braničevo region. Despot Đurađ himself went below Golubac and promised Jeremija forgiveness, and tried in every way to win back the city; not only did Jeremija decline, but he also attacked the despot's entourage which had tried to enter the city gates. In the spring of 1428 a new Hungarian army arrived at Golubac and besieged it from the land and from the Danube. The importance of the city is further evident from the fact that Sigismund himself led the army. But also Sultan Murat laid personal effort to encourage and support his acquired positions; in late May, after Sigismund, he arrived in the Braničevo area. Not wanting to enter combat with the superior Ottomans, Sigismund hastened to make peace. When the Hungarians in the first days of June began withdrawing, the Ottoman commander Sinan-beg attacked their back, where Sigismund was, however, with the self-sacrifice of Marko de Sentlaszlo, they were saved from disaster. During these conflicts, south and eastern Serbia were very devastated, including the developed Daljš Monastery near Golubac. From a monastery document, Sigismund is for the first time called "Our Emperor" (naš car), unlike the Ottoman sultan, who was called a pagan or non-Christian Emperor (car jezičeski).[2]

When the Ottomans captured Thessalonica in 1430, Branković paid ransom for many of its citizens but could not avoid his vassal duties and sent one of his sons to join Ottoman forces when they besieged Durazzo and attacked Gjon Kastrioti.[3]

In the beginning of Đurađ's reign, the Serbian capital was moved to Smederevo (near Belgrade) after he built a large fortress on the confluence of Danube and Jezava in 1430. After he was appointed as a successor to his uncle Stefan Lazarević, Branković's rule was marked by constant conflicts interchanging between Hungary and the Ottomans, as he temporarily lost Kosovo and Metohija in his early reign. Branković allied himself with the Kingdom of Hungary. In 1439 the Ottomans captured Smederevo, the Branković's capital. The prince fled to the Kingdom of Hungary where he had large estates, which included Zemun, Slankamen, Kupinik, Mitrovica, Stari Bečej, Kulpin, Čurug, Sveti Petar, Perlek, Peser, Petrovo Selo, Bečej, Arač, Veliki Bečkerek, Vršac, etc.

Despot Branković traveled from Hungary to Zeta, accompanied with several hundred cavalry and his wife Eirene. He first went to Zagreb, to his sister Katarina who was a wife of Ulrich II, Count of Celje.[4] Then he arrived to Dubrovnik at the end of July 1440 and after several days continued his journey toward his coastal towns of Budva and Bar[5] which became new capitol of the remaining part of his despotate. In August 1441 Branković arrived to Bar where he stayed until the end of the winter 1440–41.[6][7] There he tried to mobilize forces to recapture territory of the Serbian Despotate he lost to Ottomans.[6] During his visit to Zeta he maintained communication with garrison in Novo Brdo.[8] Branković faced another disappointment in Zeta where Crnojevići rebelled against Duke Komnen (Serbian: Војвода Комнен) the governor of Zeta.[6][9] Branković left Zeta in April 1441.[10] He first stayed in Dubrovnik which angered Ottomans who requested that Dubrovnik should hand over Branković. The Ragusans refused this request with the explanation that Dubrovnik is a free city which accepts anybody who seeks shelter in it. They also emphasized that it was better for Branković to be in Dubrovnik as this was the best guarantee that he would not undertake any action against the Ottomans.[11]

Crusade of Varna

Following the conflicts that concluded 1443, Branković had a significant role in the Battle of Niš and Battle of Zlatica and consequently in facilitating the Peace of Szeged (1444) between Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottomans. Murad II, who also desired peace, was married to Branković's daughter Mara.[12] On March 6, 1444, Mara sent an envoy to Branković; their discussion started the peace negotiations with the Ottoman Empire.[13] This peace restored his Serbian rule, but Branković was forced to bribe John Hunyadi with his vast estates. On 22 August 1444 the prince peacefully took possession of the evacuated town of Smederevo.

The peace was broken in the same year by Hunyadi and king Władysław III of Poland during the Crusade of Varna, which culminated in the Battle of Varna. A crusading army led by Regent John Hunyadi of Hungary was defeated by Sultan Murad II's forces at Kosovo Polje in 1448. This was the last concerted attempt in the Middle Ages to expel the Ottomans from southeastern Europe. Although Hungary was able to successfully defy the Ottomans despite the defeat at Kosovo Polje during Hunyadi's lifetime, the kingdom fell to the Ottomans in the 16th century. Branković also captured Hunyadi at Smederevo for a short time when he was retreating home from Kosovo in 1448, due to their personal feud.

Return and death

.jpg.webp)

Following Hunyadi's victory over the Mehmet II at the Siege of Belgrade on 14 July 1456, a period of relative peace began in the region. The sultan retreated to Adrianople, and Branković regained possession of Serbia. Before the end of the year, however, the 79-year-old Branković died. Serbian independence survived him for only another three years, when the Ottoman Empire formally annexed his lands following dissension among his widow and three remaining sons. Lazar, the youngest, poisoned his mother and exiled his brothers, and the land returned to the sultan's subjugation.[14]

Person

His portrait in the illuminated manuscript of Esphigmenou (1429) depicts him with a mild beard, while the French nobleman Bertrandon de la Broquière who guested Đurađ in 1433 said of him "nice lord and large [in person]". He was deemed by contemporaries as the richest monarch in all of Europe; Broquière stated that his annual income from the gold and silver mines of Novo Brdo amassed to about 200,000 Venetian ducats. Among other sources of income, there were possessions in the Kingdom of Hungary, for which expenses were covered by the Hungarian crown. The annual income from them alone was estimated to 50,000 ducats.

Legacy

He is included in the The 100 most prominent Serbs by the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. The character of Đurađ Branković is portrayed by Baki Davrak in the Netflix original historical docudrama Rise of Empires: Ottoman (2020).[15]

Titles

- "Despot of the Kingdom of Rascia and Lord of Albania" (Nos Georgius dei gracia Regni Rascie despotus et Albanie dominus and illustres principes, dominus Georgius, regni Rascie despotus et dominus Albanie).[16]

- "Despot of all of the Kingdoms of Rascia and Albania" (illustris princeps, dux et despotus totius regni Rascie et Albanie), by Sigismund in 1427.[17]

- "Despot and Duke of Rascia" (illustris Georgius despotus seu dux Rascie), by Sigismund in 1429.[18]

- "Lord of Rascia [and] Albania" (Georgius Wlk Rascie Albanieque dominus), in 1429.[19]

- "Lord, Despot of the Serbs" (gospodin Srbljem despot), by Constantine of Kostenets in 1431.[20]

- "Lord of the Serbs and Pomorije and Podunavije" (Господин Србљем и Поморију и Подунавију), in several official documents.[21]

- "Despot, Lord of the Serbs and the Zetan Maritime" (господин Србљем и поморју зетскому).[22]

- "Prince, Despot of the Kingdoms of Rascia and Albania" (illustrissimus princeps Georgius despotus regni Rascie et Albanie, Rive et totius Ussore dominus), in 1453.[19]

Marriage and children

Đurađ and Eirene Kantakouzene had at least six children:[23]

- Todor (d. before 1429). Not mentioned in the Masarelli manuscript, probably died early

- Grgur (c. 1415–1459). Mentioned first in the Masarelli manuscript. Father of Vuk Grgurević, also blinded with Stefan in 1441.

- Mara (c. 1416–1487). Mentioned second in the Masarelli manuscript. Married Murad II of the Ottoman Empire.

- Stefan (c. 1417–1476). Mentioned third in the Masarelli manuscript. Blinded with hot irons in 1441.[12] Claimed the throne of Serbia following the death of his younger brother Lazar.

- Katarina (c. 1418–1490). Married Ulrich II of Celje. Mentioned fourth in the Masarelli manuscript.

- Lazar (c. 1421/27–1458). Mentioned fifth and last in the Masarelli manuscript.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Đurađ Branković | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- Ćirković 2004, p. 88-91.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 103-104.

- Radovan Samardžić (1892). Istorija srpskog naroda: Doba borbi za očuvanje i obnovu države 1371–1537. Srpska knjiiževna zadruga. p. 239. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- Slavisticheskiĭ sbornik. Matica. 1989. p. 100.

... жене Улриха Целског, а потом у Бар (Зету је jош сачувао од Турака).

- Povijest Bosne i Hercegovine: od najstarijih vremena do godine 1463. Hrvatsko kulturno društvo Napredak. 1998. p. 497. ISBN 978-9958-840-00-5.

- Fine 1994, p. 531.

- Stanojević, Stanoje; Stranjaković, Dragoslav; Popović, Petar (1934). Cetinjska škola: 1834–1934. Štamparija Drag. Gregorića. p. 7.

- Божић, Иван (1952). Дубровник и Турска у XIV и XV веку. Научна књига. p. 86.

- Godišnjak – Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti, Belgrad. Srpska akademija nauk i umetnosti. 1929. p. 286.

На стр. 16 — 17 .г. Д-Ь пише: »(1) У примор(у ^е деспот (ЪураЬ) пмао да доживи ново разочаран>е. Зетом је управл>ао у иье- гово време војвода Комнен. (2) Против њега се побунише браЬа ЪурашевиЬи или Црноје- виЬи.

- Odjeljenje društvenih nauka. Društvo za nauku i umjetnost Crne Gore. 1975.

- Божић, Иван (1952). Дубровник и Турска у XIV и XV веку. Научна књига. p. 88.

- Florescu, Radu R.; Raymond McNally (1989). Dracula, Prince of Many Faces: His Life and His Times. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

- Imber, Colin (July 2006). "Introduction" (PDF). The Crusade of Varna, 1443–45. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 9–31. ISBN 0-7546-0144-7. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- Miller, William (1896). The Balkans: Roumania, Bulgaria, Servia, and Montenegro. London: G.P. Putnam's Sons. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

- "Rise of Empires: Ottoma". IMDb. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- József Teleki (gróf) (1853). Hunyadiak kora Magyarországon. Emich és Eisenfels könyvnyomdája. pp. 243–.

- Denkschriften. In Kommission bei A. Hölder. 1920.

König Sigismund nennt ihn 1427 ‚illustris princeps, dux et despotus totius regni Rascie et Albanie'.2 In seinen eigenen ... nach Bestätigung des Despotentitels regelmäßi<r ‚Georgius dei gratia regni Rascie despotus et Albanie dominus etc.

- Monographs. Naučno delo. 1960. p. 188.

... jyrca 1429 г. издатом у Пожуну, kojhm крал» Жигмунд flaje деспоту (illustris Georgius despotus seu dux Rascie) у посед „Torbaagh vocata in comitatu

- Radovi. 19. 1972. p. 30.

Georgius Wlk Rascie Albanieque dominus [...] illustrissimus princeps Georgius despotus regni Rascie et Albanie, Rive et totius Ussore dominus

- Recueil de travaux de l'Institut des études byzantines. Institut. 2006. p. 38.

- Лазо М Костић (2000). Његош и српство. Српска радикална странка. ISBN 978-86-7402-035-7.

Деспот Ђурађ Бранковић се више пута званично обележава као "Господин Србљем и Поморију и Подунавију", па га тако означава историк Чед. Мијатовић у веома лепој студији о њему, означава га тако у самом наслову студије ...

- Сима Ћирковић; Раде Михальчић (1999). Лексикон српског средњег века. Knowledge. p. 436.

господин Србљем и поморју зетскому

- Cawley, Charles, Profile of Đurađ, Medieval Lands database, Foundation for Medieval Genealogy,

References

- Andrić, Stanko (2016). "Saint John Capistran and Despot George Branković: An Impossible Compromise". Byzantinoslavica. 74 (1–2): 202–227.

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Isailović, Neven (2016). "Living by the Border: South Slavic Marcher Lords in the Late Medieval Balkans (13th–15th Centuries)". Banatica. 26 (2): 105–117.

- Isailović, Neven G.; Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2015). "Serbian Language and Cyrillic Script as a Means of Diplomatic Literacy in South Eastern Europe in 15th and 16th Centuries". Literacy Experiences concerning Medieval and Early Modern Transylvania. Cluj-Napoca: George Bariţiu Institute of History. pp. 185–195.

- Ivanović, Miloš (2016). "Foreigners in the Service of Despot Đurađ Branković on Serbian territory". Banatica. 26 (2): 257–268.

- Ivanović, Miloš; Isailović, Neven (2015). "The Danube in Serbian-Hungarian Relations in the 14th and 15th Centuries". Tibiscvm: Istorie–Arheologie. 5: 377–393.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers.

- Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2017). "Which Realm will You Opt for? – The Serbian Nobility Between the Ottomans and the Hungarians in the 15th Century". State and Society in the Balkans Before and After Establishment of Ottoman Rule. Belgrade: Institute of History, Yunus Emre Enstitüsü Turkish Cultural Centre. pp. 129–163.

- Orbini, Mauro (1601). Il Regno de gli Slavi hoggi corrottamente detti Schiavoni. Pesaro: Apresso Girolamo Concordia.

- Орбин, Мавро (1968). Краљевство Словена. Београд: Српска књижевна задруга.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Paizi-Apostolopoulou, Machi (2012). "Appealing to the Authority of a Learned Patriarch: New Evidence on Gennadios Scholarios' Responses to the Questions of George Branković". The Historical Review. 9: 95–116.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Stanković, Vlada, ed. (2016). The Balkans and the Byzantine World before and after the Captures of Constantinople, 1204 and 1453. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Đurađ Branković. |

- Shedding New Light on the Ties of Mara Branković to the Holy Mountain of Athos and transletion of Relics

- Saint John Capistran and Despot George Branković: An Impossible Compromise

- Order of Despot Đurađ Branković to St. Paul's Monastery, Mount Athos

- Despot Đurađ's Heritage, Smederevo

- The Esphigmen Charter of Despot Đurađ Branković issued to the monastery of Esphigmen on Mount Athos in 1429

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Stefan Lazarević |

Despot of Serbia 1427–1456 |

Succeeded by Lazar Branković |