Yellow River Map

The Yellow River Map, Scheme, or Diagram (河圖, with variants for the second character) is an ancient Chinese concept. It is related to the Lo Shu Square. The origins of the two from the rivers Luo and He are part of Chinese mythology. The development of the two are part of Chinese philosophy. (Wu:52)

| Yellow River Map (He Tu) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

河圖 River Scheme | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 河圖 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 河图 | ||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Hétú | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Yellow River's Map/Diagram/Plan | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Geographical background

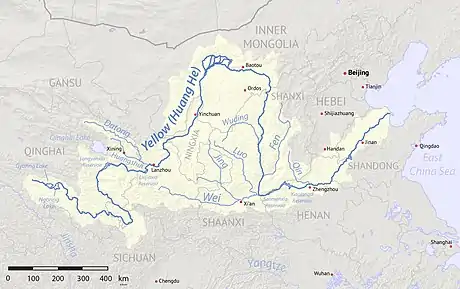

The Yellow River or Huang He is the second-longest river in Asia, following the Yangtze River, and the sixth-longest in the world. The Yellow River has an estimated length of 5,464 km (3,395 mi). It has been and remains an important factor for human habitability of northern China. Anciently, it was often referred to just as He or "the River", and thus the Yellow River Map, just as "River Map" or "River Plan". The Yellow River has changed its course, settling in new beds, with different outlets to the ocean, many times in the past, often accompanied by death and devastation to the human population. Flowing through the yellow loess soil deposited as a deep, packed dust across much of northern China, it gets its name from the yellow color of resulting suspended solids. The Lo, or Luo, River is a major tributary.

Mythological background

Myths of the Yellow River Map go back to earliest stages of the recorded history of Chinese culture.

Great Flood

The Great Flood of China, also known as the "Gun-Yu myth" (Yang:74), was a major flood event that continued for at least two generations, which resulted in great population displacements among other disasters, such as storms and famine: according to mythological and historical sources, it is traditionally dated to the third millennium BCE, during the reign of the Emperor Yao. Treated either historically or mythologically, the story of the Great Flood and the heroic attempts of the various human and other characters to control it and to abate the disaster is a narrative fundamental to Chinese culture. Among other things, the Great Flood of China is important to understanding the history of the founding of both the Xia Dynasty and the Zhou Dynasty, it is also one of the main flood motifs in Chinese mythology, and it is a major source of allusion in Classical Chinese poetry. Various divine or heroic persons or beings contributed to control or in some cases worsen the flooding, including the mysterious bird-turtles of the Heavenly Questions of the Chuci. One of the main (if not the main) rivers involved according to tradition was the Yellow River, and one of the keys to the eventual successful efforts to control the flood waters is traditionally the Yellow River Map.

Fu Xi

Fu Xi, also known as Paoxi, is still actively worshipped in modern China. Fu Xi was a culture hero credited with his sister Nüwa with repopulating the world in the aftermath of a great flood, as well as with establishing civilization afterwards. Among his inventions was the Yellow River Map, from which he derived the first trigrams which later composed the I Ching.

Yu

Yu is often known as Yu the Great, especially in English language sources. He succeeded Gun in flood control. Yu the Great (c. 2200–2100 BCE) was a legendary ruler in ancient China famed for his introduction of flood control, inaugurating dynastic rule in China by founding the Xia Dynasty, and for his acclaimed upright moral character.

He Bo

The deity ("Count" or "Earl") of the Yellow River is He Bo. According to some accounts he was involved with the production of the Yellow River Map. However, which historically came first remains unresolved, the cultural tradition of the Yellow River Map, or that of the Yellow River Earl (He Bo).

Houtu

Houtu (Chinese 后 土 ) is a male, female or non-gendered divinity, depending on source, although the image of a Sacred Mother Earth deity is common. Houtu is currently worshiped in Chinese popular religion, with her birthday on the 18 day of the Third Moon in the Chinese lunar calendar. Sacrifice and prayer to Houtu are believed to be efficacious for problems of weather, reproduction and family, wealth, and boating safety on the Yellow River. (Yang, et al.:136–137) According to one account, when Yu "the Great" was attempting to channel the Yellow River and so to avoid its flooding, Yu began by trying to open it to the west (towards the mountains and away from the sea, thus completely the wrong way). Observing this, Houtu is said (in this version) to have created and studied the Yellow River Map, after which she sent her divine messenger birds to Yu "the Great" to tell him to open up the river to the east, instead. Yu's new dredging was a success, the flood waters drained into the eastern sea, and Yu's former dredging project toward an impossible western drainage was named "River Wrongly Opened". (Yang, et al.:137) In this version of the story, Houtu and the Yellow River Map were key to the successful engineering solution to the flood problem.

Bagua

Bagua is a main concept in Chinese combinatoric philosophical thought: 8 figures of mythical origin and emblematic significance that are specifically said to be related to the Yellow River Map and the Luoshu Square. Although these concepts originate in prehistory, much has been written about them since, evolving a complex body of literature, some of it more esoteric, and some less so. Derivation of the bagua has been conceived philosophically according to the taiji or other system in which original unity, symbolized by the bottom circle first differentiates into yin and yang symbolized by solid versus dashed lines. 8 possible unique groupings of these lines into three-line sets are possible. These sets of 3 are known as "trigrams". Each trigram has its own proper name, in Chinese, and is also considered to possess or to symbolize various qualities of the natural, human, or heavenly worlds. Certain traditions suppose that the Yellow River Map and the Luo River Writing reveal all of these things to one who knows how to read them.

Cosmological background

The concept of the Yellow River Map has a contextual apparatus associated with ancient Chinese cosmology. Various myths or legends are connected with the idea of mapping, involving correspondences between the earth, the sky, and/or abstract diagrams. The idea of a simple division of a flat/square earth into the very basic 3x3, (9-square) grid is historically attested in literature as early as the Tian Wen's "Heavenly Questions", together with a suggested corresponding mapping solution for a round heaven/the sky (Hawkes, 136–137 [notes to Tian wen]). This text from the Chu Ci dates to pre-221 BCE. This basic grid is associated with the plan of Yu to control the Great Flood of China (Hawkes, 139).

Historical evidence

The Yellow River Map is attested to in the Gu Ming section of the Book of Documents (one of the "new text" sections). Supposedly, the Yellow River Map was put on display during the Zhou dynasty; however, this has also been interpreted to mean a depiction of the 8 trigrams (bagua) (Wu:52–53, and note 14, 102). This incident is recorded to have been during the reign of King Kang of Zhou, about 1020–996 BCE or 1005–978 BCE.

Literature

The Yi Jing (also known as the Book of Changes, or I Ching) cites the "Yellow River Map" and the "Lo Shu Square" (or "script"). (Wu:52)

Interpretation

Interpretation of "Yellow River Map"

One way of analyzing the Yellow River Map is by comparison with the Luo (or Lo) River Plan (or "Square"). Wolfram Eberhard (in his Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: in the article under the title "Square", 276) says that the River Plan is proven "beyond a reasonable doubt" to be a magic square. He connects it to the mingtang halls of worship, saying that they share a division into 9 fields: these in turn are correlated with the 9 "planets" (Sun, Moon, Mercury, Mars, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Rahu, and Ketu), introduced from and according to Indian astronomy. Other sources emphasize these points for the Luo River Writing. Another interpretation of the River Diagram has to do with the 5 "elements" (wuxing) and the 5 cardinal directions. Anyway, according to James Legge the earliest versions appear to no longer be extant, with received versions going back only to Song dynasty (early Twelfth Century); concluding, "If we had the original form of 'the River Map,' we should probably find it a numerical trifle, not more difficult, not more supernatural, than the Lo Shu Magic Square" (Legge, intro:15–18). Nevertheless, Legge finds it of interest in interpreting the I Ching.

Interpretation of I Jing

First of all, Legge notes that the little bright circles of the "Map" correspond with the "whole" (yang) lines of the I Ching and that the little dark circles of the "Map" correspond with the "divided" (yin) lines thereof (Legge, intro:16).

Wuxing

| fire (火) 7 (extinction) 2(generation) | ||

| wood (木) 8 (extinction) 3 (generation) | earth (土) 5 (generation) 10(extinction) | metal (金) 4 (generation) 9 (extinction) |

| 1 (generation) 6 (extinction) water (水) |

- Notes:

- Extinction is: 成數, which could also be translated as "completion".

- Generation is: 生數, which could also be translated as "birth".

- 10 is represented in the Chinese (as are the other numerals) with a (different) single character: 十.

Odd number order (1, 3, 5, 7, 9)

| x | 7(west, 西) | x |

| 3(south, 南) | 5(center, 中) | 9(north, 北) |

| x | 1(east, 東) | x |

Even number order (2, 4, 6, 8, 10)

| x | 2(west, 西) | x |

| 8(north, 北) | 10(center, 中) | 4(south, 南) |

| x | 6(east, 東) | x |

Places

Certain places in modern China use Hétú (河图) as part of their proper place names. These include 河图镇 (岳西县), 河图镇 (保山市), and 河图乡.

See also

- Loess Plateau, the highly erodable land through which the Yellow River finds its course.

- Longma, dragon-horse creature, mythological delivery beast of the Yellow River Map.

- Lo Shu Square, companion piece to the River Map (actually named the "Luo" (or "Lo") "Script" or "Writing").

- Luo River (Henan)

- Luo River (Shaanxi)

- Mount Buzhou, an important geographic feature, in relevant mythology.

References

- Christie, Anthony (1968). Chinese Mythology. Feltham: Hamlyn Publishing. ISBN 0600006379.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (2003 [1986 (German version 1983)]), A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00228-1

- Hawkes, David, translation, introduction, and notes (2011 [1985]). Qu Yuan et al., The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044375-2

- Legge, James, translator. The I Ching: The Book of Changes Second Edition New York: Dover, 1963 (1899). Library of Congress 63-19508

- Wu, K. C. (1982). The Chinese Heritage. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-517-54475X.

- Yang, Lihui, et al. (2005). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533263-6