Yaakov Yitzchak of Peshischa

Yaakov Yitzchak Rabinowicz of Peshischa (Yiddish: יעקב יצחק ראבינאוויטש פון פשיסחא; c. 1766 – October 13, 1813) also known as the Yid Hakudosh (lit. 'the Holy Jew') or the Yehudi was the founder and first Grand Rabbi of the Peshischa movement of Hasidic philosophy, and an important figure of Polish Hasidism. The leading disciple of Yaakov Yitzchak of Lublin, the Yehudi preached an "elitist" approach to Hasidism, in which he parred traditional Talmudic learning with the highly spiritual Kavanah of Hasidism. He encouraged individuality of thought, which brought his movement into conflict with the Hasidic establishment. Nevertheless, several of his teachings would go on to influence large percentages of modern Hasidism. Following his death in 1813, he was succeeded by his main disciple Simcha Bunim of Peshischa, who increased his movement's influence tenfold. The Yehudi is the patriarch of the Porisov and Biala Hasidic dynasties.[1]

Yaakov Yitzchak of Peshischa | |

|---|---|

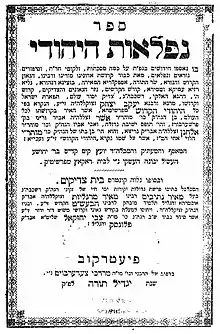

Frontpage of "Niflos HaYehudi" ("Wonders of the Holy Jew") published posthumously in 1908 in Piotrków Trybunalski. | |

| Title | Yid Hakudosh (ייִד הקדוש) |

| Personal | |

| Born | Jakub Izaak Rabinowicz 1766 |

| Died | October 13, 1813 |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Spouse | (1) Braindel Koppel, (2) Sheindel Freida Koppel |

| Children | Yerachmiel Rabinowicz, Nehemia Jehiel Rabinowicz, Joshua Asher Rabinowicz, Sarah Leah Rabinowicz, Rebecca Rachel Rabinowicz |

| Parents |

|

| Jewish leader | |

| Predecessor | Yaakov Yitzchak of Lublin |

| Successor | Simcha Bunim of Peshischa |

| Ended | 1813 |

| Yahrtzeit | 19 Tishrei |

| Buried | Przysucha, Poland |

Early life

Yaakov Yitzchak Rabinowicz was born in 1766 in Przedbórz, Poland. His father Asher Rabinowicz of Przedbórz was a maggid and the Av Beit Din of Przedbórz. His father was the great-grandson of Isaac HaLevi Segal, who was in part, the great-grandson of Eliezer Treves of Frankfurt who was a descendant of Rashi.[2] In his early years, he studied under David Tevele of Lissa and Aryeh Leib Halperin whom he followed to Opatów, where he was introduced to Hasidism by Moses Leib of Sasov. He spent several years teaching in the local yeshivot and married Braindel Koppel, the daughter of the wealthy innkeeper Jacob Koppel of Opatów. Following this, he became a disciple of David of Lelov who convinced the Yehudi to travel to the Hasidic court of Yaakov Yitzchak Horowitz (the Seer) in Lublin. During his time in Lublin, the Yehudi soon becoming the leading disciple of the Seer, who affectionally called him the "Yehudi" so that he would not be called by his rebbe's name. As the Seer became preoccupied with the responsibilities of mass movement he began directing newly-arrived young scholars visiting Lublin into the care of the Yehudi. However, over time, the Yehudi began to greatly resent the atmosphere in Lublin. In the court of the Seer, the rebbe served as the impetus of God and worked within a mystical and kabbalistic framework. The Yehudi began to detest the all-encompassing role in which the Seer played within his follower's lives, and so he founded his own religious movement based in Przysucha (Peshischa). Several of the Seer's most distinguished disciples followed the Yehudi to Przysucha, such as Simcha Bunim of Peshischa and Menahem Mendel of Kotsk. This break from the Seer was dramatically recounted in Martin Buber's "Gog Und Magog".[3][4]

Rabbinic position

The Yehudi believed that an individual should always examine his intentions, and if they are corrupt he should cleanse them through a process of understanding. Once famously saying "God's seal is 'truth,' it can not be forged, since if it is forged it is true no more".[5] It was this fundamental belief in individuality and autonomy of self which resulted in a continuous dispute between the Seer and the Yehudi. The Seer believed that it was his duty to bring an end to the Napoleonic wars, by using Kabbalah, and asked the Yehudi to join this spiritual endeavour, the latter refused, believing that one finds redemption through a highly personal process of self-cleansing.[3] The Yehudi believed that humility is the core virtue of a person who truly knows himself, recognizing his own imperfection. He also believed that one should not be influenced by the status quo as it can lead to impure motives. The Yehudi stated that "Each person should have two sides, after showing one to himself he will not be troubled by others and will be able to show the other to the rest of the world" [6] In this, the Yehudi expresses the fundamental ideal of authenticity. Believing that if one has faults, they should be open about said faults instead of living in a place of shame.[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Peshischa Hasidism |

|---|

| Rebbes |

|

| Disciples |

|

| Other figures |

|

The Yehudi believed that the path to enlightenment required critical judgment of religious routine, stating that "all the rules that a person makes for himself to worship God are not rules, and this rule is not a rule either".[7] The Yehudi removed himself from earthly desires, such as sex or eating, believing that it was his specific path to self-cleansing. This stood in staunch contrast with the materialistic nature of the Seer, who believed that self-cleansing was done through miracles tied to the rebbe. The Yehudi believed that the main role of the rebbe was to guide his disciples in their struggle for spiritual depth, and not to serve as a miracle-worker. This teaching appealed to the followers of Peshischa, who were an elite and highly educated group of young Hasidim who were willing to sacrifice their material well-being as well as their inner peace in the name of self-cleansing.[3]

The Yehudi believed that one of the main paths to self-cleansing was the parring of traditional Talmudic learning with the deeply spiritual Kavanah of Hasidism. Unlike his Hasidic contemporaries, the Yehudi believed that Learning Talmud became central to the worship of God stating that "learning Talmud and Tosafot purifies the mind and makes one ready for praying" [8] Ultimately the Yehudi believed that critical search for truth was crucial to enlightenment, and that process of enlightenment could only be done by an individual rather than through a rebbe. After his death in 1813, the Yehudi was succeeded by his main disciple Simcha Bunim of Peshischa who brought the movement its highest point and kickstarted a counter-revolutionary

movement that challenged the Hasidic norm.

Legacy

.JPG.webp)

During his life, the Yehudi wrote no works of his own, but many of his teachings were transmitted orally and published, much later on after his death. The following are collections of the Yehudi's oral teachings:

- Nifla'ot ha-Yehudi (נפלאות היהודי) – Published in 1908 in Piotrków Trybunalsk by Baruch ben Avraham of Kasov.

- Tiferet ha-Yehudi (תפארת היהודי) – Published in 1912 in Warsaw by Baruch ben Avraham of Kasov.

- Torat ha-Yehudi (תורת היהודי) – Published in 1911 in Bilgoraj by Yaakov ben Zeev Yehuda Orner.

His eldest son, Yerachmiel married Golda, daughter of Dov, the Av Beit Din of Bila Tserkva, their son Natan David Rabinowicz founded the Biala Hasidic Dynasty. The Yehudi's second son, Joshua Asher of Parysów married Lili Halberstadter, the daughter of Naftali Zvi Halberstadter and founded the Porisov Hasidic dynasty, their son Yaakov Zvi Rabinowicz authored "Atarah LeRosh Tzadik". The Yehudi's third son, Nehemia Jehiel of Bychawa married the daughter of Hayyim of Bila Tserkva, their son Haim Gedalliah Rabinowicz was a Admor in Bychawa. The Yehudi's eldest daughter, Rivka Rochel married Moshe Biderman of Lelov, son of Rabbi Dovid of Lelov, their son Eleazar Mendel Biderman of Lelov was the Third Grand Rabbi of the Lelov Hasidic dynasty. The Yehudi's youngest child, Sarah Leah married Samuel Raphaels of Józefów , their daughter Braindel Faiga Raphaels married Avraham Moshe Bonhardt of Peshischa, son of Rabbi Simcha Bunim Bonhardt of Peshischa. Their son, Tzvi Hersh Mordechai Bonhardt was a Admor in Przysucha.[2]

References

Citations

- Britannica 2020.

- Dynner 2006, p. 314.

- Encyclopaedia Judaica 2020.

- Rosen 2008, p. 15-16,20-21.

- Kosov 1912, p. 50.

- Kosov 1912, p. 76.

- Kosov 1912, p. 96.

- Kosov 1912, p. 29.

Bibliography

- Dynner, Glenn (2006). Men of Silk: The Hasidic Conquest of Polish Jewish Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199785148.

- Britannica (2020). Jacob Isaac ben Asher Przysucha. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc.

- Encyclopaedia Judaica (2020). Przysucha (Pshishkha), Jacob Isaac ben Asher. Encyclopaedia Judaica.

- Rosen, Michael (2008). The Quest for Authenticity: the thought of Reb Simhah Bunim. Urim Publications. ISBN 9789655240030. OCLC 190789076.

- Kosov, Baruch ben Avraham (1912). Tiferes haYehudi. Torah Database.