xkcd

xkcd, sometimes styled XKCD,[‡ 2] is a webcomic created in 2005 by American author Randall Munroe.[1] The comic's tagline describes it as "A webcomic of romance, sarcasm, math, and language".[‡ 3][2] Munroe states on the comic's website that the name of the comic is not an initialism but "just a word with no phonetic pronunciation".

| xkcd | |

|---|---|

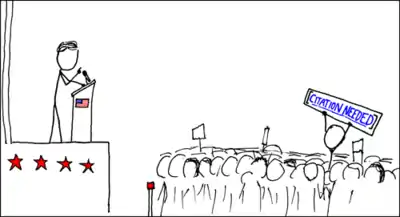

Panel from "Philosophy"[‡ 1] | |

| Author(s) | Randall Munroe |

| Website | xkcd.com |

| Current status/schedule | Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays |

| Launch date | September 2005[1] |

| Genre(s) | Comedy, Geek humor |

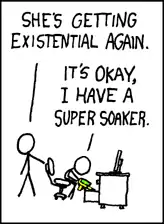

The subject matter of the comic varies from statements on life and love to mathematical, programming, and scientific in-jokes. Some strips feature simple humor or pop-culture references. It has a cast of stick figures,[3][4] and the comic occasionally features landscapes, graphs, charts, and intricate mathematical patterns such as fractals.[5] New cartoons are added three times a week, on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.[‡ 2][6]

Munroe has released four spinoff books from the comic. The first book, chronologically, published in 2010 and entitled xkcd: volume 0 was a series of select comics from his website. His 2014 book What If? is based on his blog of the same name that answers unusual science questions from readers in a light-hearted way that is scientifically grounded.[‡ 4][‡ 5][7] The What If column on the site is updated with new articles from time to time. His 2015 book Thing Explainer explains scientific concepts using only the one thousand most commonly used words in English.[‡ 6][8] A fourth book, How To, which is described as "a profoundly unhelpful self-help book," was released on September 3, 2019.[‡ 7]

History

As a student, Munroe often drew charts, maps, and "stick figure battles" in the margins of his school notebooks, besides solving mathematical problems unrelated to his classes. By the time he graduated from college, Munroe's "piles of notebooks" became too large and he started scanning the images.[9]

xkcd began in September 2005, when Munroe decided to scan his doodles and put them on his personal website. According to Munroe, the comic's name has no particular significance and is simply a four-letter word without a phonetic pronunciation, something he describes as "a treasured and carefully guarded point in the space of four-character strings." In January 2006, the comic was split off into its own website, created in collaboration with Derek Radtke.[10]

In May 2007, the comic garnered widespread attention by depicting online communities in geographic form. Various websites were drawn as continents, each sized according to their relative popularity and located according to their general subject matter.[‡ 8][11] This put xkcd at number two on the Syracuse Post-Standard's "The new hotness" list.[12] By 2008, xkcd was able to financially support Munroe and Radtke "reasonably well" through the sale of multiple thousand T-shirts per month.[10]

On September 19, 2012, "Click and Drag" was published, which featured a panel which can be explored via clicking and dragging its insides.[‡ 9] It immediately triggered positive response on social websites and forums.[13] The large image nested in the panel measures 165,888 pixels wide by 79,822 pixels high.[14] Munroe later described it as "probably the most popular one I ever put on the Internet", as well as placing it among his own favorites.[9]

"Time" began publication at midnight EDT on March 25, 2013, with the comic's image updating every 30 minutes until March 30, when they began to change every hour, lasting for over four months. The images constitute time lapse frames of a story, with the tooltip originally reading "Wait for it.", later changed to "RUN." and changed again to "The end." on July 26. The story began with a male and female character building a sandcastle complex on a beach who then embark on an adventure to learn the secrets of the sea. On July 26, the comic superimposed a frame (3094) with the phrase "The End". Tasha Robinson of The A.V. Club wrote of the comic: "[...] the kind of nifty experiment that keeps people coming back to XKCD, which at its best isn't a strip comic so much as an idea factory and a shared experience".[15] Cory Doctorow mentioned "Time" in a brief article on Boing Boing on April 7, saying the comic was "coming along nicely". The 3,099-panel "Time" comic ended on July 26, 2013, and was followed by a blog post summarizing the journey.[‡ 10][16] In 2014, it won the Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story.

Around 2007, Munroe drew all the comics on paper, then scanned and processed them on a tablet computer (a Fujitsu Lifebook).[‡ 11] As of 2014, he was using a Cintiq graphics tablet for drawing (like many other cartoonists), alongside a laptop for coding tasks.[17]

Influences

Munroe has been a fan of newspaper comic strips since childhood, describing xkcd as an "heir" to Charles M. Schulz's Peanuts. Despite this influence, xkcd's quirky and technical humor would have been difficult to syndicate in newspapers. In webcomics, Munroe has said that "one can draw something that appeals to 1 percent of the audience—1 percent of United States, that is three million people, that is more readers than small cartoons can have." Munroe cited the lack of a need for editorial control due to the low bar of access to the Internet as "a salvation."[10]

Recurring themes

While there is no specific storyline to the webcomic, there are some recurring themes and characters.[18] Recurring themes of xkcd include "technology, science, mathematics and relationships."[2] xkcd frequently features jokes related to popular culture, such as Guitar Hero, Facebook, Vanilla Ice, and Wikipedia.

There are many strips opening with the words "My Hobby:", usually depicting the nondescript narrator character describing some type of humorous or quirky behavior. However, not all strips are intended to be humorous.[18] Romance and relationships are frequent themes, and other xkcd strips consist of complex depictions of landscapes.[18] Many xkcd strips refer to Munroe's "obsession" with potential Velociraptor attacks.[19]

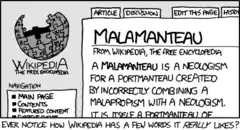

References to Wikipedia articles or to Wikipedia as a whole have occurred several times in xkcd.[‡ 12][‡ 13] A facsimile of a made-up Wikipedia entry for "malamanteau" (a stunt word created by Munroe to poke fun at Wikipedia's writing style) provoked a controversy within Wikipedia that was picked up by various media.[20][21] Another strip depicted an example of a topic that Wikipedia could not cover neutrally—a fictional donation to either anti-abortion or abortion-rights activists, determined by the word count in a Wikipedia article on the event where the donation was announced being either odd or even.[‡ 15] Wikipedia is also depicted as an extension of one's mind, allowing them to access far more information than normally.[22]

All xkcd strips have a tooltip (specified using the title attribute in HTML), the text of which usually contains a secondary punchline or annotation related to that day's comic.[23]

One of the only recurring characters is a man wearing a flat black hat. He is extremely sociopathic, and has dedicated his life to causing confusion and harm to others just for his own entertainment. He has no name, though he is commonly referred to as "Black Hat" or "Black Hat Guy" in the community. He gained a girlfriend, commonly named "Danish" by the community, during the course of a small series called "Journal", who is just as cruel as he is.[‡ 16]

Another recurring character is a man with a beret, sometimes simply referred to as "Beret Guy". He seems to be naive, obsessed with bakeries, optimistic, and completely out of touch with reality. He also has magical abilities,[24] which often manifest in the creation of situations or objects that support his overly optimistic worldview, even when in direct violation of societal norms or the laws of physics; an example is his startup making incredible amounts of money despite his not even knowing what they do. In one instance, he hired Lin-Manuel Miranda as an engineer and, in another instance, sprouted literal "endless wings".[‡ 17]

Geographical maps, their various different formats and creation methods are a frequently recurring theme in the comic.[‡ 18] On occasion these maps have been mentioned by analysts due to their imaginative or original presentation of figures or statistics. In the comic "2016 Election Map", colored stick figures are used to display how people voted according to their region giving a clearer picture of how people voted in the 2016 election. Alan Cole, a student[25] at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, critically analyzed the map, concluding that it is the most elegant and informative he has seen.[26]

Spiders have also featured frequently in xkcd, almost always in a negative light. This began very early, with the 8th xkcd comic, Red Spiders, which began a series showing the arachnids attacking humans.[27] Other comics related to spiders include Ballooning, Coronavirus Name, Cirith Ungol, and a number of others,[28] and his related What-If articles have featured terrifying machines that resemble spiders.[29] Munroe has said he dislikes eating lobster, considered by most people a delicacy, because to him it is too similar to eating spiders.[30]

Inspired activities

On several occasions, fans have been motivated by Munroe's comics to carry out the subject of a particular drawing or sketch offline.[18] Some notable examples include:

- Richard Stallman was confronted by students dressed as ninjas before speaking at the Yale Political Union[31][32] – inspired by "Open Source".[‡ 19]

- On September 23, 2007, hundreds of people gathered at Reverend Thomas J. Williams Park, 42.39561°N 71.13051°W, in North Cambridge, Massachusetts, whose coordinates were mentioned in "Dream Girl".[‡ 20] Munroe appeared, commenting, "Maybe wanting something does make it real", reversing the conclusion he drew in the last frame of the same strip.[18][33] This park is recognized by NASA's Spot The Station program, which provides information on viewing opportunities for the International Space Station.[34]

- When animated xkcd strip "Time" won a Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story in August 2014, it was accepted by Cory Doctorow on behalf of Munroe, dressing as Munroe had drawn him in an earlier strip, "1337: Part 5".[35][‡ 21]

- xkcd readers began sneaking chess boards onto roller coasters after "Chess Photo" was published.[36][‡ 22] – inspired by "Chess Photo".[‡ 23]

- The game of "geohashing"[37] has gained more than 1,000 players,[38] who travel to random coordinates calculated by the algorithm described in "Geohashing".[‡ 24]

- In October 2007, a group of researchers at University of Southern California Information Sciences Institute conducted a census of the Internet and presented their data using a Hilbert curve, which they claimed was inspired by an xkcd comic that used a similar technique.[39][40][‡ 25] Inspired by the same comic, the Carna botnet used a Hilbert curve to present data in their 2012 Internet Census.[41]

- Based on "Packages",[‡ 26] programmers have set up programs to automatically find an item for sale on the Internet for $1.00 every day.[42][43]

- In response to "Password Strength",[‡ 27] Dropbox shows two messages reading "lol" and "Whoa there, don't take advice from a webcomic too literally ;)" when attempting to register with the password "correcthorsebatterystaple".[44] ArenaNet recommended that Guild Wars 2 users create secure passwords following the guidelines of the same comic.[45]

- The Python Standard Library module "antigravity", when run, opens the xkcd comic "Python".[‡ 28][46]

- Inspired by the xkcd comic "Online Communities 2",[‡ 29] Slovak artist Martin Vargic created the "Map of the Internet 1.0."[47]

- In 2008, Munroe posted a parody of the Discovery Channel's I Love the World advertising campaign on xkcd,[‡ 30] which was later reenacted by Neil Gaiman, Wil Wheaton, and Cory Doctorow.[48]

Awards and recognition

xkcd has been recognized at various award ceremonies. In the 2008 Web Cartoonists' Choice Awards, the webcomic was nominated for "Outstanding Use of the Medium", "Outstanding Short Form Comic", and "Outstanding Comedic Comic", and it won "Outstanding Single Panel Comic".[49] xkcd was voted "Best Comic Strip" by readers in the 2007 and 2008 Weblog Awards.[50][51] The webcomic was nominated for a 2009 NewNowNext Award in the category "OMFG Internet Award".[52][53]

Randall Munroe was nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Fan Artist in both 2011 and 2012,[54][55] and he won a Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story in 2014, for "Time".[56]

Books

On September 2009, Munroe released a book, entitled xkcd: volume 0, containing selected xkcd comics.[‡ 31] The book was published by breadpig, under a Creative Commons license, CC BY-NC 3.0,[57] with all of the publisher's profits donated to Room to Read to promote literacy and education in the developing world. Six months after release, the book had sold over 25,000 copies. The book tour in New York City and Silicon Valley was a fundraiser for Room to Read that raised $32,000 to build a school in Salavan Province, Laos.[58][‡ 32]

In October 2012, xkcd: volume 0 was included in the Humble Bundle eBook Bundle. It was available for download only to those who donated higher than the average donated for the other eBooks. The book was released DRM-free, in two different-quality PDF files.[59]

On March 12, 2014, Munroe announced the book What If?: Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions. The book was released on September 2, 2014. The book expands on the What If? blog on the xkcd website.[‡ 5][7] On May 13, 2015, Munroe announced a new book entitled Thing Explainer. Eventually released on November 24, 2015, Thing Explainer is based on the xkcd strip "Up Goer Five" and only uses the thousand most commonly used words to explain different scientific devices.[‡ 6]

On February 5, 2019, Munroe announced a fourth book, titled How To, which uses math and science to find the worst possible solutions to everyday problems. It was released on September 3, 2019.[‡ 7]

See also

- Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal (SMBC) - web comic in a somewhat similar vein

References

- Chivers, Tom (November 6, 2009). "The 10 best webcomics, from Achewood to XKCD". The Telegraph. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- Arthur, Charles; Schofield, Jack; Keegan, Victor; et al. (December 17, 2008). "100 top sites for the year ahead". The Guardian. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- Guzmán, Mónica (May 11, 2007). "What's Online". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. D7. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

Created by math and programming geek Randall Munroe, the xkcd comic updates every Monday with a new adventure for its cast of oddball stick figures.

- "Ad Lib, Section: Ticket". Kalamazoo Gazette. Booth Newspapers. August 17, 2006.

- "xkcd.com search: "parody week"". Ohnorobot. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- Fernandez, Rebecca (November 25, 2006). "xkcd: A comic strip for the computer geek". Red Hat Magazine. Archived from the original on March 6, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- Holly, Russell (March 12, 2014). "XKCD 'What if?' book announced by Randall Munroe". geek.com. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- Shankland, Stephen (May 13, 2015). "XKCD cartoonist's new book: 'Thing Explainer'". CNET. CBS Interactive. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Ryberg, Jonas (November 13, 2013). "Interview: XKCD's creator tells us "I'm lucky to have readers at all"". DigitalArts.

- Cohen, Noam (May 26, 2008). "This Is Funny Only if You Know Unix". The New York Times. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- Tossell, Ivor (May 18, 2007). "We're looking at each other, and it's not a pretty sight". Globe and Mail. Canada. p. 2. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- Cubbison, Brian (May 5, 2007). "PostScript: Upstate Blogroll, New Hotness, and more". Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- "'Click And Drag,' XKCD Webcomic, Rewards Explorers (IMAGES)". Huffington Post. September 9, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- "Everything You Need to Know About xkcd Comic "Click and Drag"". Geekosystem. September 19, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- Dyess, Phil (March 26, 2013). "Check out XKCD's epic multi-day animation comic". The A.V. Club. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- Hudson, Laura (August 2, 2013). "Creator of xkcd Reveals Secret Backstory of His Epic 3,099-Panel Comic". Wired. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- Edwards, Gavin (September 2, 2014). "'XKCD' Cartoonist Randall Munroe Drops Mad Science". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- Moses, Andrew (November 21, 2007). "Former NASA staffer creates comics for geeks". The Gazette. University of Western Ontario. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- O'Kane, Erin (April 5, 2007). "Geek humor: Nothing to be ashamed of". The Whit Online. Archived from the original on February 3, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ObsessiveMathsFreak (May 13, 2010). "Wikipedia Is Not Amused By Entry For xkcd-Coined Word". Slashdot. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- McKean, Erin (May 30, 2010). "One-day wonder: How fast can a word become legit?". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- "Extended Mind". xkcd. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- Trinh, Peter (September 14, 2007). "A comic you can't pronounce". Imprint Online. Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- Munroe, Randall. "Subduction License". xkcd. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- Scott, Alan (April 2, 2019). "Alan Cole, Finance, Business Economics and Public Policy". LinkedIn. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- Scott, Dylan (January 8, 2018). "This might be the best map of the 2016 election you ever see". Vox. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- "8: Red spiders - explain xkcd". www.explainxkcd.com. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- "Category:Spiders - explain xkcd". www.explainxkcd.com. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- "Alternate Universe What Ifs". what-if.xkcd.com. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- "Alternate Universe". xkcd. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- Zapana, Victor (October 18, 2007). "Stallman trumpets free software". The Yale Daily News. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- "Richard Stallman Debate". Blog of the YPU. October 18, 2007. Retrieved October 21, 2007.

- Cohen, Georgiana (September 26, 2007). "The wisdom of crowds". The Phoenix. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- "NASA Spot The Station". NASA. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- Anders, Charlie Jane (August 17, 2014). "All The Most Exciting Moments From The 2014 Hugo Awards!". io9. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- Yu, Chun (November 12, 2007). "The man hiding behind the raptor". The Tartan. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- "Geohashing wiki". wiki.xkcd.com. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- "Maps and statistics". wiki.xkcd.com. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- McNamara, Paul (October 9, 2007). "Researchers ping through first full 'Internet census' in 25 years". Buzzblog. Networkworld.com. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- "62 Days + Almost 3 Billion Pings + New Visualization Scheme = the First Internet Census Since 1982". Information Science Institute. October 9, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- "Internet Census 2012: Port scanning /0 using insecure embedded devices". Archived from the original on October 13, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- "csKw:projects:cheepcheep". Shaunwagner.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- "xkcd #576". bieh.net. November 8, 2010. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- Cluley, Graham (August 13, 2012). "Correcthorsebatterystaple – the guys at Dropbox are funny". Naked Security. Sophos. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- Kerstein, Martin (January 31, 2013). "Mandatory Password Change is Coming". GuildWars2.com. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- van Rossum, Guido (June 21, 2010). "import antigravity". The History of Python. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- Condliffe, Jamie (January 30, 2014). "This Beautiful Map of the Internet Is Insanely Detailed". Gizmodo. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- Wallace, Lewis (February 8, 2010). "Geek Heroes Sing 'We Love Xkcd'". Wired. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- "2008 List of Winners and Finalists". Web Cartoonists' Choice Awards. Archived from the original on March 10, 2009. Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- Aylward, Kevin (November 11, 2008). "The 2007 Weblog Award Winners". Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- Aylward, Kevin (January 15, 2009). "The 2008 Weblog Awards Winners". Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- "2009 NewNowNext Awards". Viacom International Inc. Archived from the original on May 20, 2009. Retrieved June 14, 2009.

- Warn, Sarah (May 21, 2009). "Photos: 2009 NewNowNext Awards". AfterEllen.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2009. Retrieved June 14, 2009.

- "Hugo Awards Page". Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- "Hugo Awards Page". Archived from the original on April 8, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- "2014 Hugo Award Winners". Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- "Sidekick for Hire — xkcd: volume 0". Breadpig. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- Ohanian, Alexis (March 15, 2010). "The xkcd school in Laos is complete! Rejoice!". Breadpig. Archived from the original on March 22, 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- "Humble eBook Bundle is Now Five Times More Hilarious!". Humble Indie Bundle. October 16, 2012. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

Primary sources

In the text these references are preceded by a double dagger (‡):

- Munroe, Randall (February 7, 2007). "Philosophy". xkcd. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- Munroe, Randall (September 11, 2010). "About xkcd". xkcd. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- Munroe, Randall. "xkcd". xkcd. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- Munroe, Randall. "What If? – The Book". whatif.xkcd.com. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- Munroe, Randall (March 12, 2014). "What if I wrote a book?". blog.xkcd.com. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- Munroe, Randall (May 13, 2015). "New book: Thing Explainer". blog.xkcd.com. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- Munroe, Randall (February 5, 2019). "How To: Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems". blog.xkcd.com. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- Munroe, Randall (May 2, 2007). "Online Communities". xkcd. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- Munroe, Randall (September 19, 2012). "Click and Drag". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- Munroe, Randall (July 29, 2013). "1190: Time". blog.xkcd.com. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- Munroe, Randall (March 16, 2007). "In which I lose the originals of the last three months of comics and the laptop I create them with". blog.xkcd.com. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- Munroe, Randall (July 4, 2007). "Wikipedian Protester". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- Munroe, Randall (May 12, 2010). "Malamanteau". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- Munroe, Randall (February 18, 2009). "Neutrality Schmeutrality". xkcd. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- Munroe, Randall (June 6, 2008). "Journal 5". xkcd. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- Munroe, Randall (August 24, 2012). "Tuesdays". xkcd. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

-

- Munroe, Randall (November 14, 2011). "Map Projections". xkcd. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ——— (June 1, 2016). "Map Age Guide". xkcd. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ——— (January 8, 2018). "2016 Election Map". xkcd. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- Munroe, Randall (February 19, 2007). "Open Source". xkcd. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- Munroe, Randall (March 26, 2007). "Dream Girl". xkcd. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Munroe, Randall (November 16, 2007). "1337: Part 5". xkcd. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- "People Playing Chess on Roller Coasters". xkcd. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- Munroe, Randall (April 16, 2007). "Chess Photo". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- Munroe, Randall (May 26, 2005). "Geohashing". xkcd. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- Munroe, Randall (December 11, 2006). "Map of the Internet". xkcd. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- Munroe, Randall (May 1, 2009). "Packages". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- Munroe, Randall (August 10, 2011). "Password Strength". xkcd. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- Munroe, Randall (December 5, 2007). "Python". xkcd. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- Munroe, Randall (October 6, 2010). "Online Communities 2". xkcd. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- Munroe, Randall (June 27, 2008). "xkcd Loves the Discovery Channel". xkcd. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- Munroe, Randall (September 10, 2009). "Book!". blog.xkcd.com. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- Munroe, Randall (October 11, 2009). "School". blog.xkcd.com. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

Further reading

- Munroe, Randall (January 8, 2007). "What xkcd means". xkcd.

- Munroe, Randall (February 2007). "Once a Physicist: Randall Munroe". Physics World. p. 43.

- Erg (March 26, 2007). "Talking xkcd with Randall Munroe". Comixtalk.com. Archived from the original on April 21, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

- "What I learned from the xkcd effect". Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. An article on the impact of xkcd topics on Google searches.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to xkcd. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: xkcd |

- Official website

- xkcd What-If

- Explain xkcd, a wiki dedicated to explaining the references found in each comic