Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicles Test Procedure

The WLTP procedure (world harmonized light-duty vehicles test procedure) is a global, harmonized standard for determining the levels of pollutants, CO2 emissions and fuel consumption of traditional and hybrid cars, as well as the range of fully electric vehicles.

| This article is part of a series on |

| Driving cycles |

|---|

| Europe |

|

NEDC: ECE R15 (1970) / EUDC (1990) (UN ECE regulations 83 and 101) |

| United States |

| EPA Federal Test: FTP 72/75 (1978) / SFTP US06/SC03 (2008) |

| Japan |

| 10 mode (1973) / 10-15 Mode (1991) / JC08 (2008) |

| Global Technical Regulations |

| WLTP (2015) (Addenda 15) |

This new protocol is Addenda No. 15 to the Global Registry (Global Technical Regulations) defined by the 1998 Agreement[1] adopted by the Inland Transport Committee of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), agreement accepted by China, Japan and the United States, and approved by the European Union.[2]

It aims to replace the previous and regional New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) as the European vehicle homologation procedure.

Its final version was released in 2015. One of the main goals of the WLTP is to better match the laboratory estimates of fuel consumption and emissions with the measures of an on-road driving condition.[3]

Since CO2 targets are becoming more and more important for the economic performance of vehicle manufacturers all over the world, WLTP also aims to harmonize test procedures on an international level, and set up an equal playing field in the global market. Besides EU countries, WLTP is the standard fuel economy and emission test also for India, South Korea and Japan. In addition, the WLTP ties in with Regulation (EC) 2009/443 to verify that a manufacturer’s new sales-weighted fleet does not emit more CO2 on average than the target set by the European Union, which is currently set at 95 g of CO2 per kilometer for 2021.[4][5]

History

The regulation took into account various national cycles such as World-wide Heavy-Duty Certification procedure (WHDC), World-wide Motorcycle Test Cycle (WMTC).[6] It also took into consideration the 1958 and 1998 Agreements, those of Japan and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) Standard Part 1066.[6]

From NEDC to WLTP standard

From 1 September 2019 all the light duty vehicles that are to be registered in the EU countries (but also in Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Turkey) must comply with the WLTP standards.[3] The WLTP replaces the old NEDC as European homologation lab-bench procedure, which was established in the 1980s to simulate urban driving condition of a passenger car.[7] In 1992 the NEDC was updated to include also a non-urban path (characterized by medium to high speeds), and finally in 1997 the CO2 emission figure have been added, too.[8] Nowadays, the NEDC cycle has become outdated, since it is not representative of the modern driving styles, since nowadays the distances and road variety a mean car has to face have changed.[9][10] The structure of the NEDC is characterized by an average speed of 34 km/h, the accelerations are smooth, stops are few and prolonged and top speed is 120 km/h.[11]

The new standard has been designed to be more representative of the real and modern driving conditions. To pursue this goal, the WLTP is 10 minutes longer than the NEDC (30 instead of 20 minutes), its velocity profile is more dynamic, consisting in quicker accelerations followed by short brakes. Moreover, the average and the maximum velocities have been increased to 46,5 km/h and 131,3 km/h respectively. The distance covered is 23,25 km (more than double the 11 kilometers of the NEDC).[4]

The key differences between the old NEDC and new WLTP test are that WLTP:[3]

- has higher average and maximum speeds

- includes a wider range of driving conditions (urban, suburban, main road, highway)

- simulates a longer distance

- has higher average and maximum drive power

- looks at steeper accelerations and decelerations

- tests optional equipment separately

As the result, the performance of the car is decreased.

| Car | NEDC autonomy | WLTP autonomy | Decrease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renualt Zoé | 400 km | 300 km | 25% |

| BMW i3 | 300 km | 245 km | 18% |

| Hyundai Kona électrique 64 kWh | 546 km | 482 km | 12% |

Test procedure

The test procedure provides a strict guidance regarding conditions of dynamometer tests and road load (motion resistance), gear shifting, total car weight (by including optional equipment, cargo and passengers), fuel quality, ambient temperature, and tyre selection and pressure.

Three different WLTC test cycles are applied, depending on vehicle class defined by power/weight ratio PWr in W/kg (rated engine power / kerb weight):

- Class 1 – low power vehicles with PWr <= 22;

- Class 2 – vehicles with 22 < PWr <= 34;

- Class 3 – high-power vehicles with PWr > 34;

Most common cars have nowadays power-weight ratios of 40–100 W/kg, so belong to class 3. Vans and buses can also belong to class 2.

In each class, there are several driving tests designed to represent real world vehicle operation on urban and extra-urban roads, motorways, and freeways. The duration of each part is fixed between classes, however the acceleration and speed curves are shaped differently. The sequence of tests is further restricted by maximum vehicle speed Vmax.

To ensure the comparability for all vehicles, thus guaranteeing a fair comparison between different car manufacturers, the WLTP tests are performed in laboratory under clear and repeatable conditions. The protocol states:[5]

- The velocity profile that the tested vehicle must repeat (indicating one speed value for each of the 1800 seconds)

- Laboratory instrumentation parameters, such as the calibration of dynamometers, gas analyzers, anemometers, speedometers or the rolling resistance of the test bench

- Environmental conditions, such as room temperature, air density, wind

- Fuel type: gasoline, diesel, LPG, natural gas, electricity, etc.

- Fuel quality, and its chemical properties

- The tolerances under which the measures are valid

- The set-up process for vehicles ahead of the test.

The last two are stricter than in the NEDC protocol, since they were used by car manufacturers to their advantage to keep CO2 values (legally) as low as possible.[10]

The procedure doesn’t indicate fixed gear shift point, as it was in the NEDC, letting each vehicle use its optimal shift points. In fact, these points depend on vehicle unique parameters as weight, torque map, specific power and engine speed.[4]

During the WLTP the impact of the model’s optional equipment is also considered. In this way the tests reflect better the emissions of individual cars, and not just the one with the standard equipment (as it was for the NEDC cycle). In fact, for a same car, the homologation procedure needs two measures: one for the standard equipment and the other one for the fully equipped model.[4] This takes into account the effect on vehicle’s aerodynamics, rolling resistance and change in mass due to the additional features.[7]

WLTC driving cycles

The new WLTP procedure relies on the new driving cycles (WLTC – Worldwide harmonized Light-duty vehicles Test Cycles) to measure the mean fuel consumption, the CO2 emissions as well as the emissions of pollutants by passenger cars and light commercial vehicles.[13]

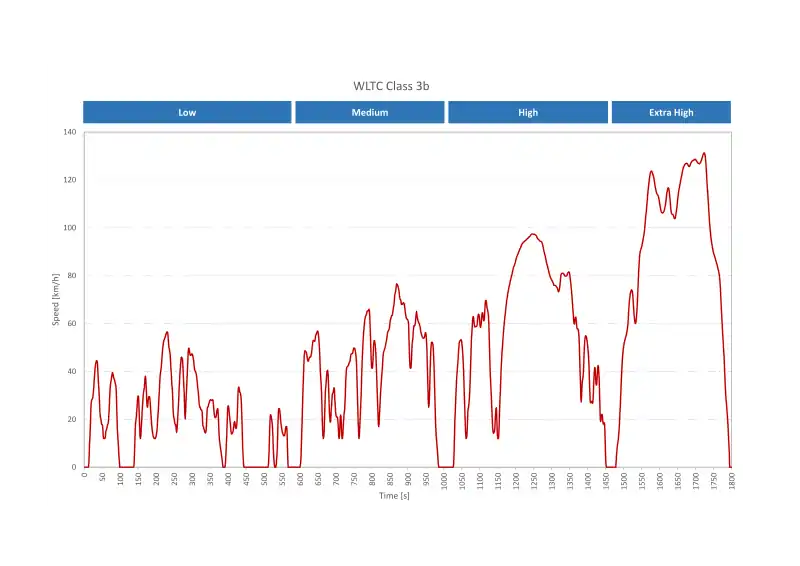

Class 3

The WLTP is divided into 4 different sub-parts, each one with a different maximum speed:

- Low, up to 56.5 km/h

- Medium, up to 76.6 km/h

- High, up to 97.4 km/h

- Extra-high, up to 131.3 km/h.

These driving phases simulate urban, suburban, rural and highway scenarios respectively, with an equal division between urban and non-urban paths (52% and 48%).[4]

| Low | Medium | High | Extra high | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration, s | 589 | 433 | 455 | 323 | 1800 |

| Stop duration, s | 150 | 49 | 31 | 8 | 235 |

| Distance, m | 3095 | 4756 | 7162 | 8254 | 23266 |

| % of stops | 26.5% | 11.1% | 6.8% | 2.2% | 13.4% |

| Maximum speed, km/h | 56.5 | 76.6 | 97.4 | 131.3 | |

| Average speed without stops, km/h | 25.3 | 44.5 | 60.7 | 94.0 | 53.5 |

| Average speed with stops, km/h | 18.9 | 39.4 | 56.5 | 91.7 | 46.5 |

| Minimum acceleration, m/s2 | -1.5 | -1.5 | -1.5 | -1.44 | |

| Maximum acceleration, m/s2 | 1.611 | 1.611 | 1.666 | 1.055 |

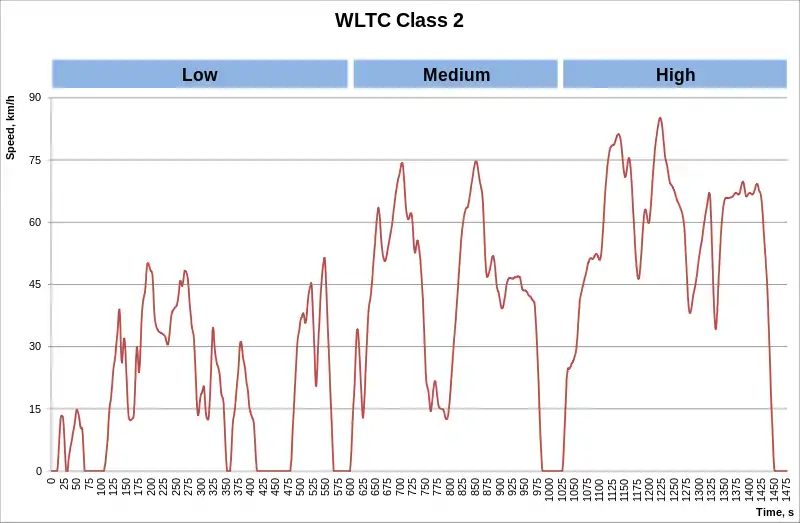

Class 2

Class 2 test cycle has three parts for low, medium, and high speed; if Vmax < 90 km/h, the high-speed part is replaced with low-speed part.

| Low | Medium | High | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration, s | 589 | 433 | 455 | 1477 |

| Stop duration, s | 155 | 48 | 30 | 233 |

| Distance, m | 3132 | 4712 | 6820 | 14664 |

| % of stops | 26.3% | 11.1% | 6.6% | 15.8% |

| Maximum speed, km/h | 51.4 | 74.7 | 85.2 | |

| Average speed without stops, km/h | 26.0 | 44.1 | 57.8 | 42.4 |

| Average speed with stops, km/h | 19.1 | 39.2 | 54.0 | 35.7 |

| Minimum acceleration, m/s2 | -1.1 | -1.0 | -1.1 | |

| Maximum acceleration, m/s2 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

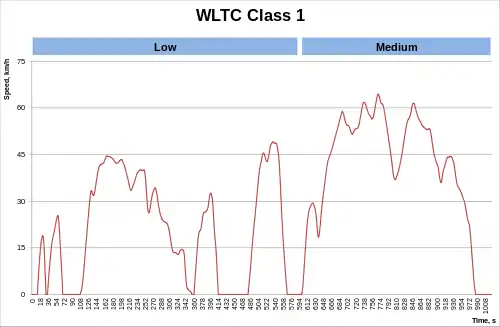

Class 1

Class 1 test cycle has low and medium-speed parts, performed in a sequence low–medium–low; if Vmax < 70 km/h, the medium-speed part is replaced with low-speed part.

| Low | Medium | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration, s | 589 | 433 | 1022 |

| Stop duration, s | 155 | 48 | 203 |

| Distance, m | 3324 | 4767 | 8091 |

| % of stops | 26.3% | 11.1% | 19.9% |

| Maximum speed, km/h | 49.1 | 64.4 | |

| Average speed without stops, km/h | 27.6 | 44.6 | 35.6 |

| Average speed with stops, km/h | 20.3 | 39.6 | 28.5 |

| Minimum acceleration, m/s2 | -1.0 | -0.6 | |

| Maximum acceleration,m/s2 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

Transition timeline from NEDC to WLTP

The period of transition from NEDC to WLTP has started in 2017 and will end in September 2019. Car manufacturers were required to obtain approval under both WLTP and NEDC for any new vehicle from 1 September 2017, while WLTP superseded NEDC from September 2018. From that date, measures of fuel consumption and CO2 emissions obtained under WLTP are the only one with legal validity and are to be inserted in official documentations (the Certificate of Conformity).[4]

Since the structures of NEDC and WLTP are different, the values obtained can differ one from the other even if the same car is being tested. As WLTP reflects more closely on-road going conditions, its laboratory measures of CO2 emissions are usually higher than the NEDC.[4] A vehicle’s performance does not change from one test from the other, simply the WLTP simulates a different, more dynamic path, reflecting in a higher mean value of pollutants. This fact is important, because the CO2 figure is used in many countries to determine the cost of Vehicle Excise Duty for new cars. Given the discrepancies in between the two procedures the UNECE suggested the policymakers to consider this asymmetry during the transition process.[3] For example in the UK, during the period of transition from NEDC to WLTP, if the CO2 value was obtained under the latter, it must be converted to a ‘NEDC equivalent’.[14]

Real drive emissions

Along with the lab-based procedure, the UNECE introduced a test in real driving conditions for NOx and other particulate emissions, which are a major cause of air pollution. This procedure is called Real Drive Emissions test (RDE) and verifies that legislative caps for pollutants are not exceeded under real use. RDE does not substitute the laboratory test (the only one that holds a legal value), but they complement it. During RDE the vehicle is being tested under various driving and external conditions, that include different heights, temperatures, extra payload, uphill and downhill driving, slow roads, fast roads, etc.[3] In addition, the freestream air that the vehicle receives is not conditioned by the wind blower position, which could cause alterations in the measured emissions of laboratory tests.[15]

To measure the emissions during the on-road test, vehicles are equipped with a portable emissions measurement system (PEMS) that monitors pollutants and CO2 values in real time. The PEMS consists in a complex instrumentation that includes: advanced gas analyzers, exhaust gas flowmeters, an integrated weather station, a Global Positioning System (GPS), as well as a connection to the network. The protocol does not indicate a single PEMS as reference, but indicates the set of parameters that its equipment has to satisfy. The collected data are analyzed to verify that the external conditions under which the measures are taken satisfy the tolerances and guarantee a legal validity.[5]

The limits on the harmful emissions are the same as the WLTP, multiplied by a conformity factor. The conformity factors consider the error of the instrumentation, that can not guarantee the same level of accuracy and repeatability of the laboratory test, as well as the influence of the PEMS itself on the vehicle that is being tested. For example, during the validation of the NOx emissions, a conformity factor of 2.1 (110% tolerance) is used.[5]

WLTP 2nd amendment

In the European Union, the WLTP 2nd amendment is Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/1832 of 5 November 2018.[16]

This regulation is for light-duty vehicles, when heavy-duty vehicles are subject to Regulation (EU) 2019/1242.

Regulation (EU) 2017/1151 sets out the requirements for the device for monitoring the consumption of fuel and/or electric energy. Recorded information includes:

- Total fuel consumed (lifetime) (litres);

- total distance travelled (lifetime) (kilometres);

- engine fuel rate (grams/second and litres/hour);

- vehicle fuel rate (grams/second);

- vehicle speed (kilometres/hour).

For hybrid vehicles:

- total fuel consumed in charge depleting operation (lifetime) (litres);

- total fuel consumed in driver-selectable charge increasing operation (lifetime) (litres);

- total distance travelled in charge depleting operation with engine off (lifetime) (kilometres);

- total distance travelled in charge depleting operation with engine running (lifetime) (kilometres);

- total distance travelled in driver-selectable charge increasing operation (lifetime) (kilometres);

- total grid energy into the battery (lifetime) (kWh).[16]

This information is stored by the On-board fuel and/or energy consumption monitoring device (OBFCM). OBFCM is mandatory since 2021 on new European cars.[16]

See also

References

- Agreement concerning the Establishing of Global Technical Regulations for Wheeled Vehicles, Equipment and Parts which can be fitted and/or be used on Wheeled Vehicles Geneva, 25 June 1998

- "United Nations Treaty Collection". treaties.un.org.

- "Worldwide harmonized Light vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP) - Transport - Vehicle Regulations - UNECE Wiki". wiki.unece.org.

- "WLTPfacts.eu - Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure". WLTPfacts.eu.

- "From NEDC to WLTP The New Test to Measure CO2 Emissions and Fuel Consumption of Cars" (PDF).

- http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trans/main/wp29/wp29r-1998agr-rules/ECE-TRANS-180a15e.pdf

- "Nuovi test di omologazione veicoli WLTP e RDE". Carpedia (in Italian).

- "Test procedure for compression-ignition (C.I.) engines and positive-ignition (P.I.) engines fuelled with natural gas (NG) or liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) with regard to the emission of pollutants".

- Stephen E. Plotkin (December 2007). "Examining Fuel Economy and Carbon Standards for Light Vehicles. Discussion Paper No. 2007-1" (PDF). OECD-ITF Joint Transport Research Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Kågeson, Per (March 1998). "Cycle beating and the EU test for cycle for cars" (PDF). Brussels: European Federation for Transport and Environment. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- E/ECE/324/Rev.2/Add.100/Rev.3 or E/ECE/TRANS/505/Rev.2/Add.100/Rev.3 (12 April 2013), "Agreement concerning the adoption of uniform technical prescriptions for wheeled vehicles, equipment and parts which can be fitted and/or be used on wheeled vehicles and the conditions for reciprocal recognition of approvals granted on the basis of these prescriptions", Addendum 100: Regulation No. 101, Uniform provisions concerning the approval of passenger cars powered by an internal combustion engine only, or powered by a hybrid electric power train with regard to the measurement of the emission of carbon dioxide and fuel consumption and/or the measurement of electric energy consumption and electric range, and of categories M1 and N1 vehicles powered by an electric power train only with regard to the measurement of electric energy consumption and electric range.

- Cycle WLTP : ce qui change pour les voitures électriques et thermiques, automobile-propre.com, 2 septembre 2018.

- "MEASUREMENT PROCEDURE FOR EXHAUST EMISSION OF LIGHT- AND MEDIUM-DUTY MOTOR VEHICLES" (PDF).

- "The Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP)". www.vehicle-certification-agency.gov.uk.

- Fernández-Yáñez, P.; Armas, O.; Martínez-Martínez, S. (2016). "Impact of relative position vehicle-wind blower in a roller test bench under climatic chamber". Applied Thermal Engineering. 106: 266–274. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.06.021.

- "Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/1832 of 5 November 2018 amending Directive 2007/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 and Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/1151 for the purpose of improving the emission type approval tests and procedures for light passenger and commercial vehicles, including those for in-service conformity and real-driving emissions and introducing devices for monitoring the consumption of fuel and electric energy (Text with EEA relevance.)". 27 November 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.