Women in the EZLN

Women have been influential in the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, a revolutionary leftist group in Chiapas, Mexico, by participating as armed insurgents and civil supporters. In the 1990s, one-third of the insurgents were women and half of the Zapatista support base was women. The EZLN organization style involved consensus and participation by everyone, including women and children.[1] Therefore, one aspect of the EZLN's ideology was gender equality and rights for women. After the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, the EZLN announced the Women's Revolutionary Law which was a set of ten laws that granted rights to women regarding marriage, children, work, health, education, political and military participation, and protected women from violence. Prominent figures who joined the movement early on such as Comandante Ramona and Major Ana Maria encouraged other women to join the Zapatistas.

Background

Indigenous Women of Chiapas

.jpg.webp)

In Chiapas during the second half of the twentieth century, indigenous women were married at a very young age, usually around thirteen or fourteen.[2] They tended to have little choice in the matter; the future husband selected a woman and the marriage was negotiated between the parents. Once married, the women fulfilled their primary roles of child-rearing, cooking, and housekeeping, though they also participated in other labor such as agriculture. Married women were often subject to mistreatment by their husbands, including physical abuse. In addition, indigenous women of Chiapas lacked access to formal education, and they typically did not learn Spanish like many men.[3] This inhibited their socioeconomic mobility because Spanish is the main language spoken in cities and used in business practices.

Indigenous Women and Internal Migration

In the 1950s, the Mexican government encouraged migration from the highlands to the Lacandon Jungle area of eastern Chiapas, the locus of the EZLN, because of demands for land reform.[4] In many cases, men forced their wives to accompany them to the jungle. Women did not want to leave because many of them had never left their villages in the highlands of Chiapas. Due to the mixing of various ethnic groups in the new location, women learned other indigenous languages and were able to communicate more broadly.[5]

There were some differences for those who stayed in the highlands. Men started working with the new businesses and industries, while women were not able to work as wage laborers. Women earned cash in other ways as street vendors or as maids in ladino homes.[6] Some of the street vendors sold handmade crafts to tourists in the cities, and these women organized into artisan collectives. They also formed other types of economic collectives such as for bread-making and vegetable gardening.[7] Rural women could also remain in their village and still contribute to the collective. This was an early instance of women organizing and working to better themselves. The maids earned cash, but suffered abuse in the ladino plantations. Physical and sexual abuse were commonly committed by the ladino landowners against the women who worked in their homes.[8] Independence, new skills, and grievances gained from these experiences led women to join the EZLN.[6]

Involvement

Military and Political Involvement

The EZLN made its first appearance on the national and international scene with the seizing of San Cristóbal de las Casas as well as six other towns in Chiapas on January 1, 1994, which coincided with Mexico entering into the North American Free Trade Agreement. This uprising declared war against the Mexican state with the issuing of the First Declaration from the Lacandon Jungle and their Revolutionary Laws. Major Ana Maria, a woman, led the capture of San Cristóbal de las Casas.

Women comprised one-third of the EZLN army, and a significant portion of them held commanding offices.[9] In addition, about half of the EZLN's support base was women.[9] Initially, the majority of the women insurgents were in the less-organized local militias, but later decided to join the actual EZLN.[10] The women who joined as insurgents had to renounce having a family of their own, because it was too difficult to care for children in the conditions they lived in. There was family planning for women insurgents, but for those who did get pregnant, they either went home or left the child with their parents. In the insurgent camps men and women share cooking and cleaning tasks equally.[11]

Joining the EZLN allowed women greater access to educational opportunities. Zapatistas spoke Spanish as a common language between the various Mayan languages. So the Zapatista women learned Spanish and also had the opportunity to learn to read and write.

Other Involvement

Despite not being actual insurgents in the EZLN, many indigenous women still supported the EZLN in other ways. These women were those who were typically older or had families to care for. The civilian women contributed by warning communities if the military arrived, operating radios to notify communities of federal troop movement, sewing uniforms, feeding troops, and more.[12]

Indigenous feminism in the EZLN

Westernization, neoliberal globalization, and the Zapatista movement affected indigenous communities in Chiapas, Mexico in that it prompted the emergence of indigenous feminism. Indigenous feminism has "its own unique flair. It is an important site of gender struggle that explicitly recognizes the vital issues of cultural identity, nationalism, and decolonization. Their struggle is based in a blend of their unique ethnic, class and gender identities. In Mexico, indigenous women, feminists or not, are deeply involved in the political and social struggles of their communities. Simultaneously to these struggles, they have created specific spaces to reflect on their experiences of exclusion as women, as indigenous and as indigenous women.”[13]

Even though feminism is seen as a result of Westernization, indigenous women have struggled to “draw on and navigate Western ideologies while preserving and attempting to reclaim some indigenous traditions...which have been eroded with the imposition of dominant western culture and ideology."[14] Indigenous feminism is invested in struggles of women, indigenous people, and look to their roots for solutions whilst using some western ideas for achieving these goals.

The women are invested in the collective struggle as the Zapatistas, and of women in general. In an interview with Ana Maria, one of the movement leaders said that the women "participated in the first of January (Zapatista Uprising)... the women’s struggle is the struggle of everybody. In EZLN, we do not fight for our own interests but struggle against every situation that exists in Mexico; against all the injustice, all the marginalization, all the poverty, and all the exploitation that Mexican women suffer. Our struggle in EZLN is not for women in Chiapas but for all the Mexicans.[15]

The effects of Western capitalist systems of development and culture makes flexibility in gender and labor roles more difficult than the indigenous cultures historical way of living off of the land. “Indigenous women’s entry into the money economy has been analyzed as making their domestic and subsistence work evermore dispensable to the reproduction of the labor force and thus reducing women’s power within the family. Indigenous men have been forced by the need to help provide for the family in the globalized capitalist economic system that favors paid economic labor while depending on female subordination and unpaid subsistence labor. These ideals are internalized by many workers and imported back into the communities.”[16] This capitalistic infiltration harmed Gender role, they were becoming more and more restrictive and polarized with the ever-growing imposition of external factors on indigenous communities. Ever since the arrival of the Europeans and their clear distinction in the views of “home/work, domestic/productive, (soon to become the public and the private” separations and distinctions began to be made, and value began being placed in different forms.

Indigenous feminism also gave rise to more collaboration and contact between indigenous and mestiza women in the informal sector. After the emergence of the Zapatistas, more meaningful collaboration started to take place, and six months after the EZLN uprising, the first Chiapas State Women's Convention was held. Six months after that, the National Women's Convention was held in Querétaro; it included the participation of over three hundred women from fourteen different states.[17] In August 1997, the first National Gathering of Indigenous Women took place in the state of Oaxaca, it was organized by indigenous women and was attended by over 400 women. One of the most prevalent issues discussed in the conventions, was the dynamics between mestizas and indigenous women. Oftentimes it became the situation where the mestizas tended to “help” and the indigenous women were the one being “helped.”

The Zapatistas’ movement was the first time a guerrilla movement held women's liberation as part of the agenda for the uprising. Major Ana Maria[18]—who was not only the woman who lead the EZLN capture of San Cristobal de las Casas during the uprising, but also one of the women who helped create the Women's Revolutionary Law,[19] ‘A general law was made, but there was no women’s law. And so we protested and said that there has to be a women’s law when we make our demands. We also want the government to recognize us as women. The right to have equality, equality of men and women.’ The Women's Revolutionary Law came about through a woman named Susana and Comandanta Ramona[20] traveling to dozens of communities and to ask the opinions of thousands of women. The Women's Revolutionary Law was released along with the rest of the Zapatista demands aimed at the government during their public uprising on New Years Day of 1994.

“For the first time in the history of Latin American guerrilla movements, women members were analyzing and presenting the “personal” in politically explicit terms. This is not to say, however, that in Zapatista communities women don't have to fight for equality and dignity. Revolutionary laws are a means, and usually a beginning, not an end. But all in all, the existence and knowledge of the law, even for women who don't actually know what it says, has had great symbolic importance as the seedling of the current indigenous women's movement in Mexico.”[21] It is important to acknowledge that not only was it a monumental move for so many women to be in the ranks and forefront of a movement, but they also went beyond that and made their own demands. They participated in the collective struggle, but also made sure their struggle was heard, acknowledged, and validated.

Women's Revolutionary Law

On the day of the uprising, the EZLN announced the Women’s Revolutionary Law with the other Revolutionary Laws. The Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee created and approved of these laws which were developed through with consultation of indigenous women. The Women’s Revolutionary Law strived to change “traditional patriarchal domination” and it addressed many of the grievances that Chiapas women had.[22] These laws coincided with the EZLN's attempt to “shift power away from the center to marginalized sectors."[23] The follow are the ten laws that comprised the Women's Revolutionary Law:

- First, women have the right to participate in the revolutionary struggle in the place and at the level that their capacity and will dictates without any discrimination based on race, creed, color, or political affiliation.

- Second, women have the right to work and to receive a just salary.

- Third, women have the right to decide on the number of children they have and take care of.

- Fourth, women have the right to participate in community affairs and hold leadership positions if they are freely and democratically elected.

- Fifth, women have the right to primary care in terms of their health and nutrition.

- Sixth, women have the right to education.

- Seventh, women have the right to choose who they are with (i.e. choose their romantic/sexual partners) and should not be obligated to marry by force.

- Eighth, no woman should be beaten or physically mistreated by either family members or strangers. Rape and attempted rape should be severely punished.

- Ninth, women can hold leadership positions in the organization and hold military rank in the revolutionary armed forces.

- Ten, women have all the rights and obligations set out by the revolutionary laws and regulations.[24]

Encuentro

In December 2007, an encuentro (gathering) was held in la Garrucha, a small indigenous village in Chiapas, for Zapatista women to discuss issues related to women. Three thousand participants attended, including approximately three hundred Zapatista women. The encuentro was considered a space for women; so men were allowed to attend the gathering, but not to participate.

These women covered topics such as their lives before the uprising, what had changed since, and how women have participated in the EZLN. Also, the Zapatista women talked about the terrible conditions that women suffered which the Zapatistas sought to fix, including: the mistreatment from working for landowners, violence at home, discrimination faced in their own communities, and lack of access to health care and education. Then, the women went on to discuss how the Zapatista movement changed their lives such as decreasing domestic violence, more freedom in regards to marriage and children, and more rights in general. One way that women achieved these changes is through the women's collectives which allowed the women to be more independent which led to increased participation in the Zapatista movement.[8]

Notable Women

Comandante Ramona

Comandante Ramona was the nom de guerre of one of the early political leaders in the EZLN.[8] She only spoke Tzotzil, and so used translators to translate between Tzotzil and Spanish.[25] Ramona worked in the communities with political organizing, but was not involved as an insurgent.[25] In February 1994 following the initial uprising, Ramona attended peace talks and served as a negotiator with the Mexican government. Ramona died on February 6, 2006 at the age of forty from kidney cancer.[26]

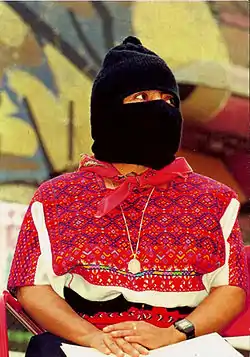

Major Ana María

Major Ana María is the nom de guerre of one of the first military leaders who led the initial 1994 uprising in San Cristóbal de las Casas, in the Southwest of México.[8] She was born in 1969, somewhere in the mountains of Los Altos de Chiapas,[27] within the Tzotzil[28] ethno-linguistic group she came from. Ana María entered the EZLN because she understood the necessity to hold land in order to ensure a better life, even more when one is woman, specially an indigenous woman. She began participating in peaceful protests at eight years old, and later joined the EZLN as one of the first women around the age of thirteen after her brother joined.[29] It is within the EZLN movement that she acquired her political opinion and learned how to use weapons.[30] She was one of the first women in the movement, and opened the path to others then led some to create women-only groups of compañeras. To her, the main demands of the EZLN movement were democracy and liberty.[31] During the seizing of San Cristobal de Las Casas, she was a Major of Infantry, she commanded a battalion of 1000 men and led them to the seizing of the Municipal Palace.[32] Therefore, she held the highest military rank in her area.[33] She helped to conceive the Women’s Law, which was a very feminist law for the time, for both indigenous and peasant women. She was part of the Comité Clandestino Revolucionario Indigena (CCRI), the Indigenous Clandestine Revolutionary Committee. Among others things, she cosigned a CCRI’s communiqué addressed to the Federal Government calling to dialogue if “the Federal Government remove his troupes of the lands controlled by the EZLN”.[34] In March 2011, Major Ana María joined the “La Marcha por el Color de la Tierra », the March for the Color of the Earth. This March lasted 37 days, to join México City from San Cristobal de Las Casas. The delegation was made of 24 EZLN’s delegate and representatives of diverse ethnic groups from all México.[35] The aim of this march was to defend the San Andrés Accords which committed the Mexican government to recognize indigenous rights and autonomy in the Constitution. However, since the firm of the Accords in 1996, which aren’t stated in the Federal Constitution, it is up to each state to recognize indigenous autonomy or not.[36]

See also

References

Footnotes

- Rodriguez, Victoria (1998). Women's Participation in Mexican Political Life. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. p. 155.

- Rovira, Guiomar (2000). Women of Maize: Indigenous Women and the Zapatista Rebellion. London: Latin American Bureau. p. 44.

- Kampwirth, Karen (2002). Women and Guerrilla Movements: Nicaragua, El Salvador, Chiapas, Cuba. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 85.

- Kampwirth 2002, p.90.

- Kampwirth 2002, p. 91.

- Kampwirth 2002, p. 93.

- Klein, Hilary (30 January 2008). "We Learn as We Go: Zapatista Women Share Their Experiences". Toward Freedom.

- Klein 2008.

- Kampwirth 2002, p. 84.

- Rovira 2000, p. 39.

- Perez, Matilde and Laura Castellanos (7 March 1994). "Do Not Leave Us Alone! Interview with Comandante Ramona". Originally published in Doble Jornada.

- Rovira 2000, p. 37.

- Hymn, Soneile. "Indigenous Feminism in Southern Mexico" (PDF). The International Journal of Illich Studies 2.

- Hymn, Soneile. "Indigenous Feminism in Southern Mexico" (PDF). The International Journal of Illich Studies 2.

- Park, Yun-Joo. "Constructing New Meanings through Traditional Values : Feminism and the Promotion of Women's Rights in the Mexican Zapatista Movement" (PDF).

- Hymn, Soneile. "Indigenous Feminism in Southern Mexico" (PDF). The International Journal of Illich Studies 2.

- Hymn, Soneile. "Indigenous Feminism in Southern Mexico" (PDF). The International Journal of Illich Studies 2.

- Women in the EZLN#Major Ana Maria

- Women in the EZLN#Women.27s Revolutionary Law

- Women in the EZLN#Comandante Ramona

- http://sites.psu.edu/illichjournal/wp-content/uploads/sites/13963/2013/06/hymn4.pdf

- Rovira 2000, p. 5.

- Rovira 2000, p. 6.

- Rodriguez 1998, p. 150.

- Perez & Castellanos 1994.

- Zwarenstein, Carlyn (11 January 2006). "Legacy of a Zapatista Rebel". The Globe and Mail.

- Rovira 2000, p. 30.

- Kampwirth 2002, p. 83.

- Rovira 2000, p. 40.

- http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/1994/03/07/comandanta-ramona-y-mayor-ana-maria-las-demandas-son-las-mismas-de-siempre-justicia-tierras-trabajo-educacion-e-igualdad-para-las-mujeres/

- http://schoolsforchiapas.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Interview-with-Major-Ana-Maria.pdf

- https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/m/marcos-weapon.html

- Rovira 2000, p. 42.

- http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/1995/02/13/entrevista-a-la-mayor-ana-maria-sobre-las-barbaridades-y-la-guerra-sucia-del-gobierno-federal/

- https://www.unilim.fr/trahs/1881

- https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/indigenous-rights-and-self-determination-mexico

Bibliography

- Kampwirth, Karen. Women and Guerrilla Movements: Nicaragua, El Salvador, Chiapas, Cuba. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002.

- Klein, Hilary. “We Learn as We Go: Zapatista Women Share Their Experiences.” Toward Freedom. January 30, 2008. http://towardfreedom.com/home/content/%20view/1224/1/.

- Perez, Matilde and Laura Castellanos. “Do Not Leave Us Alone! Interview with Comandante Ramona.” Translated by Judith and Tim Richards. Originally published in Doble Jornada, March 7, 1994. https://webspace.utexas.edu/hcleaver/www/bookalone.html.

- Rodriguez, Victoria. Women's Participation in Mexican Political Life. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1998.

- Rovira, Guiomar. Women of Maize: Indigenous Women and the Zapatista Rebellion. London: Latin American Bureau, 2000.

- Zwarenstein, Carlyn. “Legacy of a Zapatista Rebel.” The Globe and Mail. January 11, 2006. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/commentary/legacy-of-a-zapatista-rebel/article727178/.