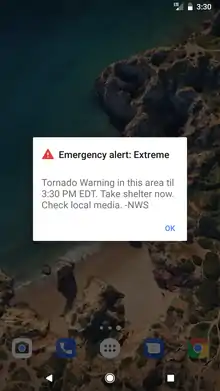

Wireless Emergency Alerts

Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA, formerly known as the Commercial Mobile Alert System (CMAS), and prior to that as the Personal Localized Alerting Network (PLAN)),[1] is an alerting network in the United States designed to disseminate emergency alerts to mobile devices such as cell phones and pagers. Organizations are able to disseminate and coordinate emergency alerts and warning messages through WEA and other public systems by means of the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System.[2]

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1983 |

| Headquarters | United States |

Background

The Federal Communications Commission proposed and adopted the network structure, operational procedures and technical requirements in 2007 and 2008 in response to the Warning, Alert, and Response Network (WARN) Act passed by Congress in 2006, which allocated $106 million to fund the program.[3] CMAS will allow federal agencies to accept and aggregate alerts from the President of the United States, the National Weather Service (NWS) and emergency operations centers, and send the alerts to participating wireless providers who will distribute the alerts to their customers with compatible devices via Cell Broadcast, a technology similar to SMS text messages that simultaneously delivers messages to all phones using a cell tower instead of individual recipients.[1][4]

The government issues three types of alerts through this system:

- Alerts issued by the President of the United States.

- Alerts involving imminent threats to safety of life, issued in two different categories: extreme threats and severe threats

- AMBER Alerts.[1]

When the alert is received, a sound is played if the ringer is on. On nearly all devices, the Emergency Alert System radio/TV attention signal sounds in a predetermined pattern.[5]

The system is a collaborative effort among the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate (DHS S&T), the Alliance for Telecommunications Industry Solutions (ATIS), and the Telecommunications Industry Association (TIA),[6]

Participation

Within ten months of FEMA making the government's design specifications for this secure interface for message transfer available, wireless service providers choosing to participate in CMAS must begin development and testing of systems which will allow them to receive alerts from alert originators and distribute them to their customers.[1] Systems must be fully deployed within 28 months of the December 2009 adoption of such standards and are expected to be delivering alert messages to the public by 2012.[6] Although not mandatory, several wireless providers, including T-Mobile, AT&T, Sprint, and Verizon have announced their willingness to participate in the system.[3] Providers who do not wish to participate must notify their customers. Some phones which are not CMAS-capable may require only a software upgrade; while others may need to be replaced entirely.[1]

CMAS messages, although displayed similarly to SMS text messages, are always free and are routed through a separate service which will give them priority over voice and regular text messages in congested areas.[1][7] Users may disable most CMAS messages; however, CMAS regulations[8] prohibit participating carriers from configuring phones to allow users to opt out of "Presidential" alerts.[1]

.gif)

Public television stations are also required by the FCC to act as a distribution system for CMAS alerts. Within 18 months of receiving funding from the Department of Commerce, all public television stations must be able to receive CMAS alerts from FEMA and transmit them to participating wireless service providers.[1]

On April 6, 2017, Canada's telecom regulator, the CRTC, ruled that all LTE wireless carriers in Canada must begin relaying public alerts effective April 2018. This system is based on style guides and behaviors dictated by the equivalent Alert Ready system used for radio and television alerting.[9][10]

In January 2018, FCC chairman Ajit Pai said the commission planned to vote on overhauling wireless alerts, with a goal to make their targeting more granular and specific, citing issues with uses of wider alerts during Hurricane Harvey, and perceptions by users that they are receiving too many alerts that do not necessarily apply to them. The FCC voted in favor of these new rules on January 30, 2018; by November 30, 2019, participating providers must deliver alerts with only a 0.1 mile overspill from their target area, require that devices be able to cache previous alerts for at least 24 hours, and that providers must support a 360-character maximum length and Spanish-language messages by May 2019.[11][12]

The first national test of a mandatory Presidential alert was held on October 3, 2018 at 2:18 PM EDT as part of a national periodic test (NPT) of the Emergency Alert System.[13][14][15] The message was expected to reach an estimated 75 percent of cell phones. Reasons for not receiving the message included carriers that did not participate in WEA, a phone that was old or otherwise not compatible, or having the phone in airplane mode or off. It is known some did not receive the message, but the exact number has yet to be determined.[16]

The lead-up to the test attracted controversy, due to the false assumption that then-president Donald Trump was personally executing the test, and reports suggesting that he could abuse the system to send personal messages similar to those he issues via social media;[17][18] A lawsuit was filed requesting a temporary restraining order blocking the test, claiming that it violated users' First Amendment rights to be free from "government-compelled listening", the system could allow the dissemination of "arbitrary, biased, irrational and/or content-based messages to hundreds of millions of people", and could frighten children. The suit was thrown out, citing that a Presidential alert can only be used to disseminate legitimate emergency messages. The judge also clarified that the test itself would be conducted and executed by FEMA employees, with no personal involvement from the President.[17][19]

National Weather Service

The Commercial Mobile Alert System (CMAS), interface to the Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) service, went live in April 2012.[20] The NWS began delivering its Wireless Emergency Alerts on June 28, 2012.[21][22]

Warning types sent via CMAS include tornado, flash flood, dust storm, hurricane, typhoon, extreme wind, and tsunami warnings; severe thunderstorm warnings are not included due to their frequency in many areas of the United States. Also, until November 2013, blizzard and ice storm warnings were also included in CMAS; they were discontinued based on customer feedback[23] due to such warnings typically issued well in advance of approaching winter storms, thus not representing an immediate hazard. While blizzard and ice storm warnings are no longer sent to phones by the National Weather Service, some local authorities continue to send winter weather related alerts at their discretion; for example in New York City during the January 2015 North American blizzard, alerts were sent to people's cell phones to warn users of a travel ban on New York City streets.[24]

Beginning Fall 2019, NWS plans to significantly reduce the amount of Flash Flood Warnings that are issued over WEA to only those with a considerable or catastrophic damage threat. It was noted that the NWS over-alerts FFWs over WEA, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has noted a large number of public complaints about overnight WEAs for FFWs with perceived little impact.[25]

As of July 2020, NWS has announced plans to implement alerts for Severe Thunderstorm Warnings labeled with a “destructive” damage threat, for wind gusts over 80 mph and hail over baseball (2.75”) size.[26]

The Snow Squall Warning is a new type of experimental warning that will begin operation out of 7 NWS offices beginning Mid-January 2018. Unlike Blizzard and Ice Storm Warnings which are issued well in advance, Snow Squall Warnings will be issued when life-threatening snow squalls that will produce strong winds and poor visibilities are occurring. These will be issued as Storm-Based Warning Polygons, like Severe Thunderstorm and Tornado Warnings. This is being considered for the nationwide WEA Program as this event requires immediate action unlike Blizzard or Ice Storm Warnings. In addition to this proposed change, the Dust Storm Warning will be polygon based, and will activate WEA. The zone-based Dust Storm Warning issued in advance will be replaced by the new Blowing Dust Warning, which will not activate WEA. Nationwide Implementation of these new events are scheduled for late 2018.[27]

Notable uses

- Boston Marathon bombing – A shelter-in-place warning was issued via CMAS by the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency.[28]

- A child abduction alert in the New York City region in July 2013 for a 7-month-old boy who had been abducted. The massive inconvenience caused by the 4:00 am timing raised concerns that many cellphone users would choose to disable alerts.[29]

- A blizzard warning in February 2013 for New York City.[30] (Note: As of November 2013, blizzard warnings are no longer included in the CMAS program.)

- A shelter-in-place warning for New York City in October 2012 due to Hurricane Sandy.[31]

- A child abduction alert in the New York City Region on June 30, 2015, for a 3-year-old girl who had been abducted.[32]

- 2016 New York and New Jersey bombings – A wanted alert was issued in New York City with a suspect's name two days after the bombings.[33]

- On January 13, 2018, a false alert of an inbound missile to Hawaii was mistakenly issued through EAS and WEA by the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency, as the result of an employee error during a routine internal system test.[34][35]

- On October 24, 2018, an alert was sent to those in the area of the Time Warner Center to shelter in place while the NYPD investigated a suspicious package sent to CNN.[36]

- An AMBER Alert issued in Utah in late-September 2019 was mocked on social media for its accompanying WEA message, which only contained the unclear shorthand "gry Toyt" (an abbreviation of "gray Toyota", referring to the suspect's vehicle).[37][38]

- WEA has been used extensively during the COVID-19 pandemic to provide notice of health guidance and stay-at-home orders. Utah attempted to use localized alerts to inform drivers entering the state that they must fill out a mandatory, online travel declaration. However, this was dropped and replaced with road signs after the state reported that the alert was being received by residents up to 80 miles away of the intended area, and that "some of them received the alert more than 15 times."[39][40][41]

Security

At the 2019 MobiSys conference in South Korea, researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder demonstrated that it was possible to easily spoof wireless emergency alerts within a confined area, using open source software and commercially available software-defined radios. They recommended that steps be taken to ensure that alerts can be verified as coming from a trusted network, or using Public-key cryptography upon reception.[42]

See also

- Integrated Public Alert and Warning System

- Emergency Alert System

- NOAA Weather Radio All Hazards

- Common Alerting Protocol

- Alert Ready (Canada)

- Emergency Mobile Alert (New Zealand)

- EU-Alert (European Union)

- NL-Alert (Netherlands)

- National Severe Weather Warning Service (UK)

References

- "Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA)". FCC.gov. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- "Integrated Public Alert & Warning System". fema.gov. Federal Emergency Management Agency. September 18, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

IPAWS provides public safety officials with an effective way to alert and warn the public about serious emergencies using the Emergency Alert System (EAS), Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Weather Radio, and other public alerting systems from a single interface.

- "Emergency alerts coming to your cellphone via SMS - GadgeTell | TechnologyTell". GadgeTell. 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- "Cell Broadcast ; One2many" (PDF). Eena.org. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- "Common audio attention signal". CFR Title 47, Part 10, §10.520. U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- "FEMA And The FCC Announce Adoption Of Standards For Wireless Carriers To Receive And Deliver Emergency Alerts Via Mobile Devices" (Press release). FEMA. December 7, 2009. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009.

- "Wireless Emergency Alerts". Ctia.org. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- "Electronic Code of Federal Regulations". GPO Access. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011.

- Freeze, Colin (6 April 2017). "Amber Alerts, other urgent warnings to be extended to cellphones by next April". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "Telecom Regulatory Policy CRTC 2017-91". CRTC. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Romm, Tony (January 8, 2018). "After Hurricane Harvey and the California wildfires, the FCC is aiming to upgrade the country's wireless alert system". Recode. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- "New FCC rules will require U.S. wireless companies to deliver emergency alerts more accurately". Recode. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- "FEMA to send its first 'Presidential Alert' in emergency messaging system test". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2018-09-15.

- Stracqualursi, Veronica. "'Presidential Alert': Trump text slides to October 3". CNN. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

- "Millions of mobiles get 'Trump alert'". BBC News. 3 October 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-03 – via www.bbc.com.

- Clodfelter, Tim (2018-10-05). "Ask SAM: Didn't get the alert on Wednesday? You're not alone". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 2018-10-05.

- "Trump's 'Presidential Alert' can't be stopped: judge". New York Post. 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- Fleishman, Glenn (2018-09-14). "You'll Probably Receive a 'Presidential Alert' From Donald Trump on Oct. 3. Here's Why". Fortune. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- "Millions of mobiles set for 'Trump alert'". BBC News. 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- "National Emergency Alert System Goes Live". Government Technology magazine. 10 April 2012.

- "Wireless Emergency Alerts: Frequently Asked Questions". Nws.noaa.gov. 2014-05-16. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- Karnowski, Steve (2012-06-28). "Weather Alerts Coming Soon to Smartphone near You". Associated Press. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- "Service Change Notice 13-71 - National Weather Service Headquarters Washington DC". National Weather Service. November 13, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- "Why NYC smartphones got blizzard alerts, but no one else did". Mashable. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- "IMPACT-BASED Flash Flood Warnings" (PDF). National Weather Service.

- "Public Information Statement 20-49" (PDF).

- "Service Change Notice 17-112 Updated".

- lbbristow (2014-06-20). "How Can Wireless Emergency Alerts Benefit Local Media? Boston Bombing Shows How". Galain Solutions. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- "Early Morning Alert Issued After 7 Month Old Boy Is Abducted". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- "Blizzard Wireless Emergency Alerts: Why Only Some People Got Them - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. 2013-02-07. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- "Hurricane Sandy Wireless Emergency Alerts: Why Only Some People Got Them - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. 2012-11-01. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- "Amber Alert canceled for 3-year-old girl abducted in East Harlem | New York's PIX11 / WPIX-TV". Pix11.com. 2015-06-30. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- Robertson, Adi (2016-09-19). "Wireless alerts sound for NYC bombing suspect". The Verge. Retrieved 2016-09-19.

- Wang, Amy B.; Lyte, Brittany (2018-01-13). "'BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII,' the alert screamed. It was a false alarm". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- Wang, Amy B. (2018-01-14). "Hawaii missile alert: How one employee 'pushed the wrong button' and caused a wave of panic". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- Gold, Michael; Peiser, Jaclyn (2018-10-24). "A Bomb Was Found at CNN Offices. Confusion in New York Followed". New York Times. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- "What was the deal with that weird 'gry Toyt' Amber Alert message?". fox13now.com. Scripps Media. 2019-09-26. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- "Infant found, vague Utah Amber Alert featuring 'gry Toyt' canceled". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- "My cellphone should have buzzed with a coronavirus emergency alert". Washington Post. 2020-03-23. Retrieved 2020-07-13.

- "Texas Cities Send Residents Alerts About Mask Requirement". Spectrum News. Retrieved 2020-07-13.

- Roberts, Alyssa (2020-04-13). "Utah no longer sending mobile COVID-19 alerts to those who cross the state line". KUTV. Retrieved 2020-07-13.

- Bode, Karl; Koebler, Jason (2019-06-26). "How the U.S. Emergency Alert System Can Be Hijacked and Weaponized". Vice. Retrieved 2019-06-27.