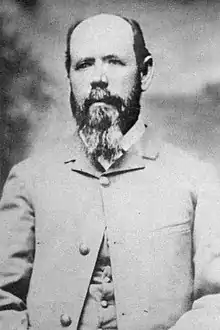

William R. Terry

William Richard Terry (March 12, 1827 – March 28, 1897) was a merchant, who became brigadier general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War and later served part-time in the Virginia Senate representing Bedford County, and still later was successively superintendent of the state penitentiary and of the soldiers' home in Richmond.[1]

William R. Terry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Virginia Senate from the Bedford County district | |

| In office October 5, 1869 – December 4, 1877 | |

| Preceded by | Robert C. Mitchell |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin H. Moulton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 12, 1827 Bedford County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | March 28, 1897 (aged 70) Chesterfield Court House, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Adelaide Pemberton |

| Profession | businessman, farmer, military officer, politician, prison superintendent |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | Brigadier General (CSA) |

| Unit | 2nd Virginia Cavalry |

| Commands | 24th Virginia Infantry |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Early and family life

William R. Terry was born in 1827 in rural Liberty in Bedford County, to William Terry Jr. and Lettie Johnson Terry, and would have at least 3 younger sisters and a younger brother. His grandfather, also William Terry had fought in the American Revolutionary War, established a plantation using enslaved labor and helped found Bedford County before his death in 1814.[2] The family's firstborn son entered the Virginia Military Institute in July 1846 and graduated on July 4, 1850, ranking 15th in a class of 17 cadets.

In 1856, Terry married Mary Adelaide Pemberton (died 1910) in Powhatan County. The couple had eight children together.[3]

Career

Terry then returned home to help his father with the farm, but the 1850 census listed his occupation as "merchant".[4] His father had for years been a prominent citizen of Bedford County, and helped get the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad through the town, owned the only steam mill (a factory that employed 7 or 8 men and made parts for agricultural implements), served as a justice of the peace and advocated for education, although at least one local historian failed to distinguish between the two men.[5] In the 1850 federal census, the elder Terry owned 52 enslaved people.[6] Ten years later, Terry owned a 20 year old Black woman in town,[7] and his father (after dowries to his daughters) only owned 20 enslaved people.[8] One author noted that prices for "Negroes" increased after March 1855, and specifically compared the average amount from the sale of the 42 slaves in William Terry's estate ($752) and that at the 1859-1860 auction of the estate of A. Turner where adult males sold for $1,750 each and females also well above $750.[9]

Confederate officer

After Virginia seceded from the Union in early 1861, Terry raised a company of cavalry in Bedford County, which became the 2nd Virginia Cavalry. His performance as captain at the First Battle of Manassas garnered attention, praise, and a promotion in September to colonel of the 24th Virginia Infantry, replacing Jubal A. Early, who had been promoted to brigade command.[10]

Leading a charge at the Battle of Williamsburg during the Peninsula Campaign, Terry suffered the worst of his several combat wounds during the Civil War. He was shot in the face and never fully recovered. He missed the Seven Days Battles, but returned to duty for the Northern Virginia Campaign in August. Later that year, he assumed temporary command of Kemper's Brigade of infantry in the Army of Northern Virginia before returning to his regimental command. Terry was wounded during Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg, and later assumed command of the severely wounded James Kemper's brigade. Pickett's rebuilt division was assigned later that year to duty in North Carolina, where it participated in the attacks on New Bern.

On May 31, 1864, Terry was promoted to brigadier general and led his depleted troops during the Battle of Cold Harbor and throughout the Siege of Petersburg. He suffered his seventh battle wound on March 31, 1865, at the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House.

Postwar career

Following the war, Terry returned to Bedford County and was elected and re-elected to the Virginia Senate, serving for a total of eight years, beginning in the first session after adoption of the Virginia Constitution of 1868.[11] He was also Master of the Liberty Masonic Lodge (1871-1872).[12]

Terry moved with his family to Chesterfield County around 1880. He also served briefly as a prison superintendent of the State Penitentiary. He was in charge of the Robert E. Lee Camp of the Confederate Soldiers' Home in Richmond, Virginia, from 1886 until 1893.

Death and legacy

Terry died in Chesterfield County, Virginia, and is buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond.[13] His family's home, Oakwood, was still standing in 1954, his father having dying shortly after the American Civil War, and his will of 1863 gave the property to his daughters Letitia Terry Whitlock and Agnes M. Terry.[14] Although a residential street is now named after the plantation, part of the property may be the location of the Bedford hospital.

In 1902, the Bedford Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was started and named after him.[15] They recently put a highway marker up at his childhood home of Oakwood in the town of Bedford, Virginia.

Notes

- Appleton's Cyclopedia Vol. VI, p. 67

- Parker p. 117

- Year: 1910; Census Place: Richmond Clay Ward, Richmond (Independent City), Virginia; Roll: T624_1644; Page: 10B; Enumeration District: 0073; FHL microfilm: 1375657for Mary A. P. Terry (his wife)

- 1850 U.S. Federal Census for Northern District family no. 740 on p. 106 of 141

- W. Harrison Daniel, Bedford County, Virginia 1840-1860 (privately printed in Bedford, Virginia in 1985)

- 1850 U.S. Federal Census for Northern District, Bedford County, Virginia pp. 64-65 of 66

- 1860 U.S. Federal Census for Liberty, Bedford County, Virginia p. 2 of 4

- 1860 U.S. Federal Census for Northern District, Bedford County, Virginia p. 67 of 68

- Daniel p. 138

- Evans, p. 674.

- Cynthia Miller Leonard, Virginia General Assembly 1619-1978 (Richmond: Virginia State Library 1978) pp. 511, 516, 520, 524.

- Lodge Minutes and Grand Lodge, A.F. & A.M. of Virginia records

- Find a Grave|10058|accessdate=2008-02-13

- Parker pp. 117-118

- Parker, Lula Jeter (1988). Parker's History of Bedford County, Virginia. Bedford, Virginia: Hamilton's. p. 47. ISBN 0960859845

References

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Evans, Clement A., ed. Confederate Military History: A Library of Confederate States History. 12 vols. Volume 3. Hotchkiss, Jed. Virginia. Atlanta: Confederate Publishing Company, 1899. OCLC 833588. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- VMI archives