William Francis Buckley

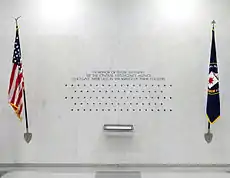

William Francis Buckley (May 30, 1928 – June 3, 1985) was a United States Army officer, a Paramilitary Officer in Special Activities Division (renamed Special Activities Center in 2016[1]) and a CIA station chief in Beirut from 1984[2] until 1985. His cover was as a Political Officer at the U.S. Embassy.[3][4] He was kidnapped by the group Hezbollah in March 1984. He was held hostage and tortured by psychiatrist Aziz al-Abub. Hezbollah later claimed they executed him in October 1985, but another American hostage disputed that, believing that he died five months prior, in June.[5][6][7] He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery and is commemorated with a star on the Memorial Wall at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

William Francis Buckley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | William Francis Buckley |

| Born | May 30, 1928 Medford, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | June 3, 1985 (aged 57) Lebanon |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1947–1985 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | U.S. Army

CIA |

| Battles/wars | Korean War Vietnam War |

| Awards | Silver Star Soldier's Medal Bronze Star with Valor device Purple Heart (2) Meritorious Service Medal Combat Infantry Badge Parachutist Badge Vietnam Gallantry Cross Distinguished Intelligence Cross Intelligence Star Exceptional Service Medal |

Early life and education

Buckley was born in Medford, Massachusetts, on May 30, 1928. After graduating from high school in 1947, he joined the United States Army. He began as a military police officer and served in that capacity for two years, but then attended Officers Candidate School (OCS) and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in Armor. He continued his military education at the Engineer Officer's Course at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, the Advanced Armor Officer's Course at Fort Knox, Kentucky, and the Intelligence School at Oberammergau, West Germany.

Career

U.S. Army

During the Korean War, Buckley served as a company commander with the 1st Cavalry Division. Next, he returned to Boston University and completed his studies, graduating with a bachelor's degree in political science. It was during this time that Buckley began his first employment with the Central Intelligence Agency, from 1955 to 1957. He was also employed as a librarian in the Concord, Winchester and Lexington public libraries. In 1960, Buckley joined the 320th Special Forces Detachment, which became the 11th Special Forces Group, and attended both Basic Airborne and the Special Forces Officers Course. He was assigned as an A-Detachment commander and later as a B-Detachment commander. Colonel Buckley served in Vietnam with the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, or MACV, as a senior advisor to the South Vietnamese Army.

CIA

In 1965 (or 1963, according to one source), Buckley rejoined the CIA in what is now called the Special Activities Division. He may have been recruited by Ted Shackley, joining his Secret Team that had been involved with Edwin Wilson, Thomas Clines, Carl Jenkins, Rafael Quintero, Félix Rodriguez and Luis Posada Carriles, in the CIA assassination program. Leslie Cockburn pointed out in her book, Out of Control (1987), that Buckley was involved in approving CIA assassinations undertaken by the Shackley organizations. In his book, Prelude to Terror (2005) Joseph Trento claims that Buckley was "one of Shackley's oldest and dearest friends."

Buckley may have been working for the CIA while in Mexico in 1963, but this is unconfirmed. His CIA employment kept him in Vietnam from 1965 to 1970, and he was promoted in his military capacity to lieutenant colonel in May 1969. After leaving Vietnam, he served in Zaire (1970–1972), Cambodia (1972), Egypt (1972–1978), and Pakistan (1978–1979).[8]

In 1983, Buckley succeeded Ken Haas as the Beirut Station Chief/Political Officer at the U.S. Embassy. Buckley was successfully rebuilding the network of agents lost in and due to the bombing of the U.S. Embassy; after the Marine Corps barracks bombing in October 1983, the Islamist group Hezbollah wrongly announced that they had also killed the CIA station chief (they did not yet know the station chief was Buckley) in the blast; their announcement was the first real indication that he was on a Hezbollah "hit list."[9]

Kidnapping and death

On March 16, 1984, Buckley was kidnapped by Hezbollah[10] from his apartment building when he was leaving for work.[6][11] It was thought that one of the reasons he was kidnapped along with two other Americans at different times in Beirut was because of the upcoming trial of 17 Iranian-backed militants that was about to begin in Kuwait. Army Major General Carl Stiner had warned Buckley that he was in danger, but Buckley told him that "I have a pretty good intelligence network. I think I'm secure." However, according to Stiner, Buckley continued to live in his apartment and travel the same route to and from work every day.[12]

William Casey, who was by then the Director of Central Intelligence, asked Ted Shackley for help in securing Buckley's release.[13] Three weeks after Buckley's abduction, President Ronald Reagan signed National Security Decision Directive 138. This directive was drafted by Oliver North and outlined plans on how to get the American hostages released from Iran and to "neutralize" alleged "terrorist threats" from countries such as Nicaragua. This new secret counter-terrorist task force was to be headed by Shackley's old friend, General Richard Secord. This was the beginning of the Iran–Contra affair, which culminated in the exchange of missiles for the release of hostages.[13]

On November 22, 1985, Ted Shackley, Buckley's friend and recruiter, traveled to the Atlantic Hotel in Hamburg, where he met General Manouchehr Hashemi, the former head of SAVAK's counterintelligence division. Also at the meeting on November 22 was Manucher Ghorbanifar. According to the report of this meeting that Shackley sent to the CIA, Ghorbanifar had "fantastic" contacts with Iran, but the CIA had designated him one year earlier as a "fabricator".[14] At the meeting, Shackley told Hashemi and Ghorbanifar that the United States was willing to discuss arms shipments in exchange for the four Americans kidnapped in Lebanon, although Buckley was already dead at this point.

Major General Carl Stiner stated that "Buckley's kidnapping had become a major CIA concern. Not long after his capture, his agents either vanished or were killed. It was clear that his captors had tortured him into revealing the network of agents he had established."[15] According to the United States, Buckley had undergone 15 months of torture by Hezbollah before his death. After Buckley's kidnapping, three videos of Buckley being tortured were sent to the CIA in Athens. Interpreters noticed puncture marks indicating he was injected with narcotics. According to several sources, as a result of his torture, he signed a 400-page statement detailing his CIA activities.[6][13][16] In a video taken approximately seven months after the kidnapping, his appearance was described as follows:

Buckley was close to a gibbering wretch. His words were often incoherent; he slobbered and drooled and, most unnerving of all, he would suddenly scream in terror, his eyes rolling helplessly and his body shaking. The CIA consensus was that he would be blindfolded and chained at the ankles and wrists and kept in a cell little bigger than a coffin.[6]

On October 4, 1985, Islamic Jihad announced that it had executed Buckley. The United States National Security Council acknowledged in an unclassified note that Buckley probably died on June 3, 1985, of a heart attack.[5][6][17] Buckley's remains were recovered by Major Jens Nielsen (Royal Danish Army) attached to the United Nations Observation Group Beirut[18] on December 27, 1991.[19] His body was returned to the United States on December 28, 1991, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, in Arlington, Virginia.[20]

Legacy

An agency memorial service was held in August 1987 to commemorate his death. A public memorial service was held with full military honors at Arlington on May 13, 1988, just short of three years after his presumed death date. At the service, attended by more than 100 colleagues and friends, CIA Director William H. Webster eulogized Buckley, saying, "Bill's success in collecting information in situations of incredible danger was exceptional, even remarkable."

Awards and decorations

Among Buckley's decorations and awards are the Silver Star, Soldier's Medal, Bronze Star Medal with "V" Device, two Purple Hearts, the Meritorious Service Medal, the Combat Infantryman's Badge, and the Parachutist Badge. He also received the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with bronze star from the Army of the Republic of Vietnam.[21] Among his CIA awards are the Intelligence Star, Exceptional Service Medallion and Distinguished Intelligence Cross. Among Buckley's civilian awards are the Freedom Foundation Award for Lexington Green Diorama, Collegium and Academy of Distinguished Alumni Boston University. The William F. Buckley Memorial Park in Stoneham, Massachusetts, is dedicated to his memory. The 51st star on the CIA Memorial Wall represents him, surrounded by about 132 other stars (as of January 2021) representing CIA officers killed in the line of duty. Approximately 35 of the stars are for unnamed agents whose identities have not been revealed for national security reasons. His name and year of death are recorded in the "Book of Honor" at the wall. The CIA awarded him the Distinguished Intelligence Cross, an Intelligence Star, and an Exceptional Service Medal, but has not said whether any of these were issued posthumously (although at least one award of the Exceptional Service Medal must have been made posthumously).

|

Intelligence Star |

|

Distinguished Intelligence Cross |

|

Exceptional Service Medal |

| 12 Overseas Service Bars |

Personal life

According to the biographical information distributed by the CIA, Buckley was "an avid reader of politics and history" and "a collector and builder of miniature soldiers." The latter hobby enabled him to become a principal artisan in the creation of a panorama at the Lexington Battlefield Tourist Center near his native Medford, Massachusetts. The press release also said he owned an antique shop and was an amateur artist and a collector of fine art. It called him "a very private and discreet individual."[22]

See also

- William R. Higgins (1945–1990)

- Imad Mughniyah (1962–2008)

References

Notes

Citations

- Slick, Stephen. "Measuring Change at the CIA".

- "Hostages in Lebanon: Israelis are guarded; another seven Americans held hostage in Lebanon". The New York Times. June 27, 1985.

- Thomas 1988.

- Kushner 2002, pp. 85–86.

- "Former Hostage Says Buckley Died Five Months Before Date Given by Captors". Associated Press. Washington, D.C. Associated Press. December 2, 1986. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- Thomas, Gordon (October 25, 2006). "The spy who never came in from the cold: William Buckley". Canada Free Press. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- Trento 2005.

- Simkin, John. "William Francis Buckley".

- Clancy & Stiner 2002, pp. 239, 253.

- Lerner, K. Lee; Wilmoth, Brenda, eds. (2015) [2004]. "Chronology". Espionage Information: Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence and Security (1st ed.). Detroit: Thomson/Gale, Advameg Inc. ISBN 978-0787675462. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- Woodward, Bob; Babcock, Charles R. (November 25, 1986). "William Buckley Murdered: Captive CIA Agent's Death Galvanized Hostage Search". Washington Post. highbeam.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2015.(subscription required)

- Clancy & Stiner 2002, p. 260.

- William Francis Buckley Archived September 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Spartacus Educational. Retrieved on July 13, 2008.

- "The Iran-Contra Affair 20 Years On". The National Security Archive 1995–2006. November 24, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- Clancy & Stiner 2002, p. 261.

- Anderson, Jack; Van Atta, Dale (September 28, 1988). "CIA Official Tortured to Death, Gave Secrets". Deseret News. Salt Lake City, Utah. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- United States National Security Council, "U.S./Iranian Contacts and the American Hostages"-"Maximum Version" of NSC Chronology of Events, dated November 17, 1986, 2000 Hours – Top Secret, Chronology, November 17, 1986, 12 pp. (UNCLASSIFIED)

- "Lebanon—UNOGIL". United Nations Peacekeeping Missions. United Nations. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- Picco 1999, pp. 334.

- "Burial Detail: Buckley, William F. (Section 59, Grave 346)". ANC Explorer. Arlington National Cemetery. (Official website).

- "Buckley, William Francis, LTC". army.togetherweserved.com. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- Binder, David (December 28, 1991). "Remains of C.I.A. Official Are Flown to U.S. for Rites". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

Sources

- Clancy, Tom; Stiner, Carl (2002). Shadow Warriors: Inside the Special Forces. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 0399147837.

- Kushner, Harvey W (2002). "William Francis Buckley". Encyclopedia of Terrorism (Hardcover). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0761924081.

- Picco, Giandomenico (1999). Man Without a Gun: One Diplomat's Secret Struggle to Free the Hostages, Fight Terrorism, and End a War. Times Books - Random House. pp. 334 (Buckley). Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- Thomas, Gordon (1988). Journey into Madness: Medical Torture and the Mind Controllers. New York: Bantam. ISBN 978-0553053579.

- Trento, Joseph (April 29, 2005). Prelude to Terror (1ST ed.). New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0786714643.

Further reading

- David Ignatius, Agents of Innocence, New York: W.W. Norton; Avon, 1988 (paperback) ISBN 978-0393317381 This book contains a thinly disguised portrait of Buckley (as Tom Rogers)

- West, Nigel. Seven Spies Who Changed the World. London: Secker & Warburg, Ltd. 1991 (hard cover). London: Mandarin, 1992 (paperback) ISBN 978-0436566035.

External links

- Peraino, Kevin (February 16, 2008). "The Death of Terror's Pioneer". Newsweek. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- William Francis Buckley at Find a Grave

- "William Francis Buckley". at ArlingtonCemetery•net. (Unofficial website).