Wilbur Smith

Wilbur Addison Smith (born 9 January 1933)[1] is a South African (Zambian-born) novelist specialising in historical fiction about the international involvement in Southern Africa across four centuries, seen from the viewpoints of both black and white families.

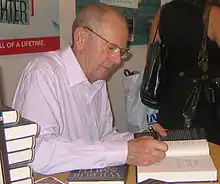

Wilbur Smith | |

|---|---|

Smith, signing The Quest | |

| Born | 9 January 1933 Broken Hill, Northern Rhodesia |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Genre | Nature, adventure |

| Website | |

| wilbursmithbooks | |

An accountant by training, he gained a film contract with his first published novel When the Lion Feeds.[2] This encouraged him to become a full-time writer, and he developed three long chronicles of the South African experience which all became best-sellers. He still acknowledges his publisher Charles Pick's advice to "write about what you know best",[3] and his work takes in much authentic detail of the local hunting and mining way of life, along with the romance and conflict that goes with it. As of 2014 his 35 published novels had sold more than 120 million copies, 24 million of them in Italy.[4]

Early life

Smith was born in Broken Hill, Northern Rhodesia (now Kabwe, Zambia). His father was a metal worker who opened a sheet metal factory and then bought a cattle ranch. "My father was a tough man", said Smith. "He was used to working with his hands and had massively developed arms from cutting metal. He was a boxer, a hunter, very much a man's man. I don't think he ever read a book in his life, including mine".[1]

As a baby, Smith was sick with cerebral malaria for ten days but made a full recovery.[5] He spent the first years of his life on his father's cattle ranch, comprising 12,000 hectares (30,000 acres) of forest, hills and savannah. On the ranch his companions were the sons of the ranch workers, small black boys with the same interests and preoccupations as Smith. With his companions he ranged through the bush, hiking, hunting, and trapping birds and small mammals. His mother read to him every night and later gave him novels of escape and excitement, which piqued his interest in fiction; however, his father dissuaded him from pursuing writing.[6]

Education

Smith attended boarding school at Cordwalles Preparatory School in Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal).[7] While in Natal, he continued to be an avid reader and had the good fortune to have an English master who made him his protégé and would discuss the books Smith had read that week. Unlike Smith's father and many others, the English master made it clear to Smith that being a bookworm was praiseworthy, rather than something to be ashamed of, and let Smith know that his writings showed great promise. He tutored Smith on how to achieve dramatic effects, to develop characters, and to keep a story moving forward.

For high school Smith attended Michaelhouse, a boarding school situated in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands.[8] He felt that he never "fitted in" with the people, goals and interests of the other students at Michaelhouse. On a positive note, he did start a school newspaper at Michaelhouse for which he wrote the entire content, except for the sports pages. His weekly satirical column became mildly famous and was circulated as far afield as The Wykeham Collegiate and St Anne's.[9]

Accountant

Smith initially worked on his father's cattle ranch and also served with the Rhodesian Police. "I would get called out and have to get bodies of children from pit lavatories after they had been killed with pangas [machetes]", he recalled.[10]

Smith wanted to become a journalist, writing about social conditions in South Africa, but his father's advice to "get a real job" prompted him to become a tax accountant (chartered accountant).[11]

"My father was a colonialist and I followed what he said until I was in my 20s and learned to think for myself", he said. "I didn't want to perpetuate injustices so I left Rhodesia in the time of Ian Smith."[10]

He attended Rhodes University in Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Commerce in 1954. He subsequently found work with the Inland Revenue Service.[12]

Novelist

First novels

Smith turned back to fiction, this time determined to write it, and found that he was able to sell his first story to Argosy magazine for £70,[13] twice his monthly salary. His first attempt at a novel, The Gods First Make Mad,[14] was rejected, so for a time he returned to work as an accountant, until the urge to write once again overwhelmed him. He tried another novel:

I wrote about my own father and my darling mother. I wove into the story chunks of early African history. I wrote about black people and white. I wrote about hunting and gold mining and carousing and women. I wrote about love and loving and hating. In short I wrote about all the things I knew well and loved better. I left out all the immature philosophies and radical politics and rebellious posturing that had been the backbone of the first novel. I even came up with a catching title, When the Lion Feeds.[15]

When the Lion Feeds tells the stories of two young men, twins Sean and Garrick Courtney. The characters' surname was a tribute to Smith's grandfather, Courtney James Smith, who had commanded a Maxim gun team during the Zulu Wars. Courtney James Smith had a magnificent mustache and could tell wonderful stories that had helped inspire Wilbur.

Smith's agent in London, Ursula Winant, managed to sell the book to William Heinemann for an advance of £2,000 and an initial print run of 10,000 copies. The book went on to be successful, selling around the world (except in South Africa, where it was banned) and enabling Smith to leave his job and write full-time.[15] Charles Pick, who bought the book for Heinemann, later became Smith's mentor and agent.[16][17] Smith says Pick gave him advice he never forgot: "Write for yourself, and write about what you know best." Pick also advised: "Don't talk about your books with anybody, even me, until they are written." Smith has said that, "Until it is written a book is merely smoke on the wind. It can be blown away by a careless word."[18]

In 2012, Smith said When the Lion Feeds remained his favourite because it was his first to be published.[19] Film rights were bought by Stanley Baker but no movie resulted. However, the money enabled Smith to quit his job in the South African taxation office, calculating he had enough to not have to work for two years.

"I hired a caravan, parked it in the mountains, and wrote the second book", he said. "I knew it was sort of a watershed. I was 30 years of age, single again, and I could take the chance."[20]

Smith's second published novel was The Dark of the Sun (1965), a tale about mercenaries during the Congo Crisis. Film rights were sold to George Englund and MGM and it was filmed in 1968 starring Rod Taylor.[21]

Smith did not originally envision the Courtney family from When the Lion Feeds would become a series, but he returned to them for The Sound of Thunder (1966), taking the lead characters up to after the Second Boer War.[22]

Shout at the Devil (1968) was a World War I adventure tale which would be filmed in 1976. It was followed by Gold Mine (1970), an adventure tale about the gold mining industry set in contemporary South Africa, based on a real-life flooding of a gold mine near Johannesburg in 1968.[23]

The Diamond Hunters (1971) was set in contemporary West Africa, later filmed as The Kingfisher Caper (1975). Around this time, Smith also wrote an original screenplay, The Last Lion (1971) which was filmed in South Africa with Jack Hawkins; it was not a success.

The Sunbird

Smith admits to being tempted by movie money at this stage of his career but deliberately wrote something that was a complete change of pace, The Sunbird (1972).[24]

It was a very important book for me in my development as a writer because at that stage I was starting to become enchanted by the lure of Hollywood. There had been some movies made of my books and I thought "whoa, what a way to go… All that money!" and I thought "hold on—am I a scriptwriter or am I a real writer?" Writing a book that could never be filmed was my declaration of independence. I made it so diffuse, with different ages and brought characters back as different entities. It was a complex book, it gave me a great deal of pleasure but that was the inspiration—to break free.[25]

Eagle in the Sky (1974) was more typical fare, as was The Eye of the Tiger (1975). Film rights for both were bought by Michael Klinger who was unable to turn them into movies; however, Klinger did produce films of Gold (1974) and Shout at the Devil (1976).

Cry Wolf (1976) was a return to historical novels, set during the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. He then returned to the Courtney family of his first novel with A Sparrow Falls (1977), set during and after World War I. Hungry as the Sea (1978) and Wild Justice (1979) were contemporary stories—the latter was his first best seller in the USA.[26][27]

He embarked on a new series of historical novels, centering around the fictitious Ballantyne family, who helped colonise Rhodesia: A Falcon Flies (1980), Men of Men (1981), The Angels Weep (1982) and The Leopard Hunts in Darkness (1984).

The Burning Shore (1985) saw him return to the Courtney family, from World War I onwards. He called this a "breakthrough" book for him "because the female lead kicked the arse of all the males in the book."[28] He stayed with the family for Power of the Sword (1986) (up to World War II), Rage (1987) (the post-war period up until the Sharpeville massacre), A Time to Die (1989) (the war in Mozambique) and Golden Fox (1990) (the Angola War).

Elephant Song (1991) was a more contemporary tale, but then he kicked off a new cycle of novels set in Ancient Egypt: River God (1993) and The Seventh Scroll (1995). He returned to the Courtneys for Birds of Prey (1997) and Monsoon (1999), then published another Ancient Egyptian story, Warlock (2001).

Blue Horizon (2003) was a historical Courtney tale and The Triumph of the Sun (2005) had the Courtneys meet the Ballantynes. The Quest (2007) was in Ancient Egypt then Assegai (2009) had the Courtneys. Those in Peril (2011) was contemporary, as was Vicious Circle (2013). Desert God (2014) brought Smith back to Ancient Egypt.

Later career: Move to HarperCollins and using co-writers

In December 2012, it was announced that Smith was leaving his English-language publisher of 45 years, Pan Macmillan, to move to HarperCollins. As part of his new deal, Smith will be writing select novels with co-writers, in addition to writing books on his own. In a press release Smith was quoted as saying: "For the past few years my fans have made it very clear that they would like to read my novels and revisit my family of characters faster than I can write them. For them, I am willing to make a change to my working methods so the stories in my head can reach the page more frequently."[29]

The first of the co-written novels was Golden Lion (2015), a Courtney novel. Predator (2016) was contemporary. Pharaoh (2016) brought him back to Ancient Egypt.[30]

Awards

In 2002, the World Forum on the Future of Sport Shooting Activities granted Smith the Inaugural Sport Shooting Ambassador Award.[31]

Personal life

Smith was working for his father when he married his first wife, Anne, a secretary, in a Presbyterian Church on 5 July 1957 in Salisbury, Rhodesia. "We got on well in the bedroom but not outside it," Smith said. "On our honeymoon, I thought: "What have I got myself into?" but resigned myself to it. "[32] There were two children of this marriage: a son Shaun was born on 21 May 1958 and then a daughter Christian. The marriage ended in 1962.

He married his second wife, Jewel, following the publication of his first novel (When the Lion Feeds, 1964) with whom he had another child, a son, Lawrence. "Everyone looked down on me, including her," he told one interviewer. "We didn't know anything about mutual respect or working together towards a goal—she thought I was useless."[33] This marriage also ended in divorce.[34] Smith later said "On honeymoon I realised I didn't know her [his second wife] well... By the time we divorced, I felt as if I'd been in two car smashes."[35]

Smith then met a young divorcée named Danielle Thomas, who had been born in the same town and had read all of his books, and thought they were wonderful. They married in 1971.[36] Smith later said "she manipulated me. I was making a lot of money and she spent it by the wheelbarrow load... she had intercepted letters from my children. She destroyed my relationship with them because she had a son from a previous marriage and wanted him to be the dauphin."[35]

Smith dedicated his books to her until she died from brain cancer in 1999, following a six-year illness.[37] Smith said:

The first part of our marriage was great. The last part was hell. Suddenly I was living with a different person. They chopped out half Danielle's brain and her personality changed. She became very difficult. I found it very, very hard to spend a lot of time with her because her moods would flick back and forth. She'd say, 'Why am I dying and you are well? It's unfair.' I'd say, 'Look, life isn't fair.' But when she passed away, I was sitting next to her, holding her hand as she took her last breath.[38]

He met his fourth wife, a Tadjik woman named Mokhiniso Rakhimova, in a WHSmith bookstore in London. The two fell in love and married in May 2000. She was a law student studying at Moscow University and younger than he by 39 years. On their relationship, Smith said:

"It really was love at first sight—and now she's got the best English teacher in the world. Of course people ask about the age gap, but I just say, 'What's 39 years?' Sure, she's young enough to be my daughter, so what?"[34]

When Smith married Danielle Thomas, he cut off contact with his son Shaun and daughter Christian. He was also estranged from his son Lawrence. "My relationship with their mothers broke down and because of what the law was they went with their mothers and were imbued with their mothers' morality in life and they were not my people any more", he said. "They didn't work. They didn't behave in a way I like. I'm quite a selfish person. I'm worried about my life and the people who are really important to me."[33] He became close to Danielle's son from a previous relationship, Dieter Schmidt, and adopted him. Smith and Shaun subsequently reconciled.[38] In 2002 he and Schmidt wound up in court in a dispute over assets and they became estranged. Smith:

"What I do, and I know it's a mistake but I just can't help myself, is I get into a relationship and I just want to give that person everything... I'm overgenerous. Then if they turn on me, I cut them off, it's finished. I'm not the easiest guy in the world, I can tell you, but if you are onside with me you can have everything, I'll lay down my life for you, you can go and help yourself to the bank account virtually. But if you let me down, then bye-bye-blackbird."[39]

He has homes in London, Cape Town, Switzerland and Malta.[40] For a number of years he had a home in the Seychelles.[1]

The Courtney series

The Courtney series is divided into three parts, each of which follows a particular era of the Courtney family.

In chronological order, the parts are Third Sequence, First Sequence, then Second Sequence. However, this is a slight generalisation, so in fact the book sequence is as follows, with publication dates in parentheses:[41]

- Birds of Prey 1660s (1997)

- Golden Lion 1670s (2015) (with Giles Kristian)

- Monsoon 1690s (1999)

- The Tiger's Prey 1700s (2017) (with Tom Harper)

- Blue Horizon 1730s (2003)

- Ghost Fire 1754 (2019)

- When the Lion Feeds 1860s–1890s (1964)

- The Triumph of the Sun 1880s (2005)

- King of Kings 1887 (2019)

- The Sound of Thunder 1899–1906 (1966)

- Assegai 1906–1918 (2009)

- The Burning Shore 1917–1920 (1985)

- War Cry 1918–1939 (2017) (with David Churchill)

- A Sparrow Falls 1918–1925 (1977)

- Power of the Sword 1931–1948 (1986)

- Courtney's War 1939 (2018)

- Rage 1950s and 1960s (1987)

- Golden Fox 1969–1979 (1990)

- A Time to Die 1987 (1989)

The Ballantyne series

The Ballantyne Novels chronicle the lives of the Ballantyne family, from the 1860s through the 1980s, against a background of the history of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The fifth novel seeks to combine the Ballantyne narrative with that of Smith's other family saga, The Courtney Novels.

The books are set in the following time periods:

- A Falcon Flies 1860 (1980)

- Men of Men 1870s–1890s (1981)

- The Angels Weep 1st part 1890s, 2nd part 1977 (1982)

- The Leopard Hunts in Darkness 1980s (1984)

- The Triumph of the Sun 1884 (2005)

- King of Kings 1887 (2019) (with Imogen Robertson)

The Ancient Egypt series

The Ancient Egypt series is an historical fiction series based in large part on Pharaoh Memnon's time, addressing both his story and that of his mother Lostris through the eyes of his mother's slave Taita, and mixing in elements of the Hyksos' domination and eventual overthrow.

- River God (1993)[42]

- The Seventh Scroll (1995)*

- Warlock (2001)

- The Quest (2007)

- Desert God (2014)[43]

- Pharaoh (2016)

* The Seventh Scroll is set in modern times but reflects the other books in the series via archaeological discoveries.[44]

Influences

As a child, Smith enjoyed reading Biggles books and Just William (1922), as well as the works of John Buchan, C. S. Forester and H. Rider Haggard.[5] Other authors he admires include Lawrence Durrell, Robert Graves, Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck.[45]

"I always think I am from the 17th century", said Smith. "I have no interest in technology, or to rush, rush, rush through life. I like to take time to smell the roses and the buffalo dung."[10]

He says he has tried to live by the advice of Charles Pick, his first publisher and mentor who became his literary agent:

He said, "Write only about those things you know well." Since then I have written only about Africa... He said, "Do not write for your publishers or for your imagined readers. Write only for yourself." This was something that I had learned for myself. Charles merely confirmed it for me. Now, when I sit down to write the first page of a novel, I never give a thought to who will eventually read it. He said, "Don't talk about your books with anybody, even me, until they are written." Until it is written a book is merely smoke on the wind. It can be blown away by a careless word. I write my books while other aspiring authors are talking theirs away. He said, "Dedicate yourself to your calling, but read widely and look at the world around you, travel and live your life to the full, so that you will always have something fresh to write about." It was advice I have taken very much to heart. I have made it part of my personal philosophy. When it is time to play, I play very hard. I travel and hunt and scuba dive and climb mountains and try to follow the advice of Rudyard Kipling; "Fill the unforgiving minute with sixty seconds' worth of distance run." When it is time to write, I write with all my heart and all my mind.[16]

Criticism

Although many respected historians and authentic news letters endorse Smith's work, some critics have accused it of not having been thoroughly researched. One of Smith's main critics, Martin Hall, asserts in his book Journal of Southern African Studies that the novels present biased, illiberal views against African nationalism. Other critics claim that misogynistic, homophobic, and racist assumptions[46][47] as well as political agendas[48] are present in these novels.

Bibliography (chronologically)

| Year | Title | Timeframe | Series |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | When the Lion Feeds | 1860s–1890s – Anglo-Zulu War | Courtney |

| 1965 | The Dark of the Sun | 1960s – Congo Crisis | – |

| 1966 | The Sound of Thunder | 1899–1906 – Second Boer War | Courtney |

| 1968 | Shout at the Devil | 1913–15 – World War I | – |

| 1970 | Gold Mine | 1960s | – |

| 1971 | The Diamond Hunters | late 1960s | – |

| 1972 | The Sunbird | modern times/ancient times | – |

| 1974 | Eagle in the Sky | modern times | – |

| 1975 | The Eye of the Tiger | modern times | – |

| 1976 | Cry Wolf | 1935 – Italian invasion of Ethiopia, Second Italo-Abyssinian War | – |

| 1977 | A Sparrow Falls | 1918–1925 – World War I, Rand Rebellion | Courtney |

| 1978 | Hungry as the Sea | modern times | – |

| 1979 | Wild Justice (known as The Delta Decision in the U.S.) | modern times | – |

| 1980 | A Falcon Flies | 1860s – white settlement of Rhodesia | Ballantyne |

| 1981 | Men of Men | 1870s–1890s – First Matabele War | Ballantyne |

| 1982 | The Angels Weep | 1st part 1890s – Second Matabele War 2nd part 1977 – Rhodesian Bush War |

Ballantyne |

| 1984 | The Leopard Hunts in Darkness | 1980s – newly independent Zimbabwe | Ballantyne |

| 1985 | The Burning Shore | 1917–1920 – World War I | Courtney |

| 1986 | Power of the Sword | 1931–1948 – World War II | Courtney |

| 1987 | Rage | 1950s and 1960s – Sharpeville massacre | Courtney |

| 1989 | A Time to Die | 1987 – Mozambican Civil War | Courtney |

| 1990 | Golden Fox | 1969–1979 – South African Border War, Cuban intervention in Angola | Courtney |

| 1991 | Elephant Song | modern times | – |

| 1993 | River God | Ancient Egypt | Egyptian |

| 1995 | The Seventh Scroll | modern times | Egyptian |

| 1997 | Birds of Prey | 1660s | Courtney |

| 1999 | Monsoon | 1690s | Courtney |

| 2001 | Warlock | Ancient Egypt | Egyptian |

| 2003 | Blue Horizon | 1730s | Courtney |

| 2005 | The Triumph of the Sun | 1880s – Siege of Khartoum | Courtney & Ballantyne |

| 2007 | The Quest | Ancient Egypt | Egyptian |

| 2009 | Assegai | 1906–1918 | Courtney |

| 2011 | Those in Peril | modern times | Hector Cross |

| 2013 | Vicious Circle | modern times | Hector Cross |

| 2014 | Desert God | Ancient Egypt | Egyptian |

| 2015 | Golden Lion | 1670s, East Africa (with Giles Kristian) | Courtney |

| 2016 | Predator | modern times (with Tom Cain) | Hector Cross |

| 2016 | Pharaoh | Ancient Egypt | Egyptian |

| 2017 | War Cry | 1918–1939 (with David Churchill) | Courtney |

| 2017 | The Tiger's Prey | 1700s (with Tom Harper) | Courtney |

| 2018 | Courtney's War | 1939-1945 WWII (with David Churchill) | Courtney[49] |

| 2019 | King of Kings | 1880–1890s (with Imogen Robertson) | Courtney & Ballantyne[49] |

| 2019 | Ghost Fire | 1754 (with Tom Harper) | Courtney[49] |

| 2020 | Call of the Raven | Early 1800s (with Corban Addison) | Ballantyne (slavery in the USA; prequel to A Falcon Flies) [49] |

Filmography

Several of Smith's novels have been turned into movies and TV shows.

- The Dark of the Sun (1965), filmed as The Mercenaries (1968) starring Rod Taylor and Yvette Mimieux

- Gold Mine (1970), filmed as Gold (1974) starring Roger Moore and Susannah York

- The Diamond Hunters (1971), filmed as The Kingfisher Caper (1975) film and as The Diamond Hunters (2001) TV series starring Roy Scheider and Alyssa Milano

- Shout at the Devil (1968), filmed as Shout at the Devil (1976) starring Roger Moore, Lee Marvin and Barbara Parkins

- Wild Justice (1979), filmed as Wild Justice but was released to video titled Covert Assassin (1993) starring Roy Scheider

- The Burning Shore (1985), filmed as Burning Shore (1991) starring Isabelle Gelinas, Derek de Lint and Jason Connery

- River God (1993) and The Seventh Scroll (1995), filmed as The Seventh Scroll (1999) TV miniseries starring Roy Scheider, Jeff Fahey and Karina Lombard

In 1976 Smith said "At first I didn't have complete control over the screenplay when my novels were turned into films. Now I tell the producer and director that they either use my screenplay or else there is no movie. That saves a lot of time."[50]

References

- Fox, Chloe (28 April 2007). "The world of Wilbur Smith, novelist". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- "Wilbur Smith Books In Publication & Chronological Order". Book Series. 2 October 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- Dismore, Richard (15 June 2018). "Life inspired by a love of Africa". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- "Wilbur Smith -". Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- "Early Days". Wilbur Smith Books. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- "Australia's premier bookshop - QBD Books". www.qbd.com.au. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- "Dymocks - Wilbur Smith - author". www.dymocks.com.au. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- "Home page". Michaelhouse.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- "School Days, Wilbur Smith Biography". Wilbur Smith Books. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- Adams, Tim (3 October 2015). "Wilbur Smith: 'Poor Cecil the lion was going downhill fast – that dentist probably did his pride a favour'". The Guardian.

- "10 Things You Didn't Know About Wilbur Smith | Youth Village Zambia". Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "University Daya". Wilbur Smith Books. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- "The first story I ever sold was to 'Argosy' magazine, which... at QuoteTab". QuoteTab. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- "Dymocks - Wilbur Smith - author". www.dymocks.com.au. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- "Good Days". Wilbur Smith Books. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- "Busy Days". Wilbur Smith Books. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- Hopper, Hedda (30 August 1965). "Africa is Poiter's Choice". The News and Courier. p. 3. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Meet Wilbur Biography: Busy Days". wilbursmithbooks.

- "Wilbur Smith: My Favourite Work is My First Book". The Tossed Salad. 31 January 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- "FEATURES A golden life crafted from a troubled land". The Canberra Times. 13 May 1995. p. 51. Retrieved 25 January 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- Webmaster. "Dark of the Sun/The Mercenaries (1967) | Nostalgia Central". Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- "Interview with Wilbur Smith". 1989. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- "'GOLD'". The Australian Women's Weekly. 23 October 1974. p. 33. Retrieved 25 January 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- "wilbur smith first wife". www.republicadominicanaoaci.com. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- "Wilbur Smith answers your questions", BBC News, 6 April 2009 accessed 14 March 2013

- Edwin McDowell (20 April 1980). "BEHIND THE BEST SELLERS: Wilbur Smith". The New York Times. p. BR10.

- N.R. KLEINFIELD (15 June 1980). "The Sellers of Book Rights: A Big-Money World: Subsidiary Rights". The New York Times. p. F1.

- Kerridge, Jake (14 September 2014). "Wilbur Smith interview for Desert God: 'My life is as good as it's ever been'". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Wilbur Smith Moves to HarperCollins". HarperCollins Publishers.

- Black, Eleanor (24 October 2015). "Wilbur Smith at 82: "I've never been happier" With his 36th novel topping bestseller lists and a hot young wife at his side, life is peachy for Wilbur Smith". Stuff.

- "Wilbur Smith". WFSA. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 5 November 2005.

- I was described as a sex machine: [Final 1 Edition] Petty, Moira. The Times6 Apr 2005: 9.

- Midgley, Dominic (15 December 2015). "How a life devoid of PR spin has made Wilbur Smith every interviewer's dream subject".

- "Passion and piracy with Wilbur Smith". HeraldScotland. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- BOOK REVIEWS: THESPIAN TENDENCIES ; Q & A WITH WILBUR SMITH: BUY IT Sutton, Henry. The Daily Mirror 25 Mar 2005: 14.

- "The secluded life that inspires best-sellers". The Australian Women's Weekly. Australia. 7 April 1982. p. 56. Retrieved 15 January 2020 – via Trove.

- "Worst Days". Wilbur Smith Books. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- Thomas, David (29 March 2005). "Wilbur the womanizer". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- Moss, Stephen Moss (2 April 2005). "Stalking an old bull elephant". The Age. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- Anstead, Mark (19 June 2010). "Fame & Fortune: Wilbur Smith". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- "The Courtney Series in Order: How to read Wilbur Smith books?". How To Read Me. 20 August 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- Smith, Wilbur (1993). River God. Macmillan. ISBN 9781447267102.

- Smith, Wilbur (2014). Desert God. William Morrow (HarperCollins). ISBN 9780062276452.

- "THE SEVENTH SCROLL". Wilbur Smith Books.

- "Wilbur Smith, author of Those in Peril, answers Ten Terrifying Questions". Booktopia. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- "The 1960s: writing in opposition". SouthAfrica.info. 19 April 2001. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- "Beware Wilbur Smith's Gaboon Adder" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- Martin Hall, "The Legend of the Lost City; Or, the Man with Golden Balls". Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Jun., 1995), pp. 179-199.

- "The Books | Wilbur Smith".

- "People". The Australian Women's Weekly. 8 December 1976. p. 14. Retrieved 25 January 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wilbur Smith. |