White Mexicans

White Mexicans (Spanish: Mexicanos blancos) are Mexicans who are considered white, typically due to European or other Western Eurasian descent. While the Mexican government does conduct ethnic censuses in which a Mexican has the option of identifying as "White"[9] the results obtained from these censuses are not published. What Mexico's government publishes instead is the percentage of "light-skinned Mexicans" there are in the country, with it being 47%[4] in 2010 and 49% in 2017.[10] Due to its less directly racial undertones, the term "Light-skinned Mexican" has been favored by the government and media outlets over "White Mexican" as the go-to choice to refer to the segment of Mexico's population who possess European physical traits[11] when discussing different ethno-racial dynamics in Mexico's society. Nonetheless, sometimes "White Mexican" is used.[12][13][14][15][16]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Mexico Estimates range 11 million to 59 million[1][2][3][4] 9–47% of Mexican population[2] United States 16,794,111[5] 5.4% of United States population 33.3% of Hispanic and Latino Americans | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Sonora, Sinaloa, Baja California Sur, Baja California Norte, Durango, Jalisco, Nayarit, San Luis Potosí | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish, Venetian (Chipilo Venetian), Plautdietsch[6] | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (predominantly Roman Catholicism, minority Protestantism), Judaism, Mormonism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other White Latin Americans · Other White Hispanic · Spaniards · Italians · French · Germans[7] | |

a Mexican Americans |

Estimates of Mexico's white population differ greatly in both methodology and percentages given; unofficial sources such as the World Factbook and Encyclopædia Britannica, which use the 1921 census results as the base of their estimations, calculate the White Mexican population as only 9%[1] or between one tenth to one fifth of the population.[2] The results of the 1921 census, however, have been contested by various historians and deemed inaccurate.[17] Surveys that account for phenotypical traits and have performed actual field research suggest rather higher percentages: using the presence of blond hair as reference to classify a Mexican as white, the Metropolitan Autonomous University of Mexico calculated the percentage of said ethnic group within the institution at 23%.[18] With a similar methodology, the American Sociological Association obtained a nationwide percentage of 18.8%.[19] Another study made by the University College London in collaboration with Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History found that the frequencies of blond hair and light eyes in Mexicans are of 18% and 28% respectively,[20] nationwide surveys in the general population that use as reference skin color such as those made by Mexico's National Council to Prevent Discrimination and Mexico's National Institute of Statistics and Geography report percentages of 47%[3] and 49%[10][9] respectively.

Europeans began arriving in Mexico during the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire; and while during the colonial period most European immigration was Spanish, in the 19th and 20th centuries large waves of European and European-derived populations from North and South America did immigrate to the country. According to 20th and 21st century academics, large scale intermixing between the European immigrants and the native Indigenous peoples would produce a Mestizo group which would become the overwhelming majority of Mexico's population by the time of the Mexican Revolution. However, according to church and censal registers from the colonial times, the majority of Spanish men married with Spanish women.[21][17] Said registers also put in question other narratives held by contemporary academics, such as European immigrants who arrived to Mexico being almost exclusively men or that "pure Spanish" people were all part of a small powerful elite, as Spaniards were often the most numerous ethnic group in the colonial cities[22][23] and there were menial workers and people in poverty who were of complete Spanish origin.[21]

Another ethnic group in Mexico, the Mestizos, is characterized by having people with varying degrees of European ancestry and Amerindian heritage, with some even showing a European genetic ancestry higher than 90%.[24] However, the criteria for defining what constitutes a Mestizo varies from study to study as in Mexico a large number of European descended people have been historically classified as Mestizos because after the Mexican revolution the Mexican government began defining ethnicity on cultural standards (mainly the language spoken) rather than racial ones.[25]

Distribution and estimates

Contrary to popular belief, Mexico's government does conduct ethnic censuses on which a Mexican has the choice of identify as "White",[9] the results, however, remain unpublished. Instead the Mexican government does publish results regarding the frequencies of different phenotypical traits in Mexicans such as skin color, and in discourses and investigations regarding problematics such as racism has opted for splitting Mexicans on "light skinned Mexicans" and "dark skinned Mexicans" rather than on "White Mexicans" and "Mestizo Mexicans". Other studies made by independent institutions often use the presence of light hair colors (particularly blond) to calculate Mexico's white population, however it must be noted that to use said features to delineate said ethnic group results in a underestimation of its numbers as not all of Europe's native populations have those traits, similarly, not only people with those phenotypical features are considered to be white by the majority of Mexican society.[15][16]

_cropped.jpg.webp)

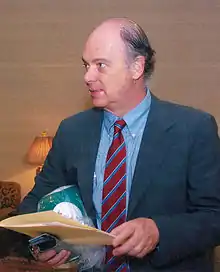

Mexico's northern and western regions have the highest percentages of white population, with the majority of the people not having native admixture or being of predominantly European ancestry, resembling in aspect that of northern Spaniards.[26] In the north and west of Mexico, the indigenous tribes were substantially smaller than those found in central and southern Mexico, and also much less organized, thus they remained isolated from the rest of the population or even in some cases were hostile towards Mexican colonists. The northeast region, in which the indigenous population was eliminated by early European settlers, became the region with the highest proportion of whites during the Spanish colonial period. However, recent immigrants from southern Mexico have been changing, to some degree.[2]

.jpg.webp)

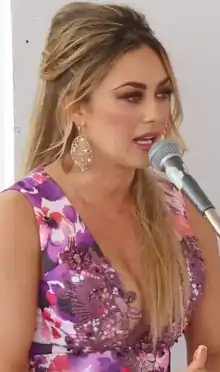

In 2010, the CONAPRED (Mexico's National Council for the Prevention of Discrimination) conducted the ENADIS 2010 (National Survey About Discrimination)[4] with the purpose of addressing the problems of racism that Mexicans of mainly Indigenous or African ancestry suffer at hands of a society that favors light-skinned, European-looking Mexicans.[11] In the press release of said report, the CONAPRED stated that 47% of Mexicans (54% of women and 40% of men) identified with the lightest skin colors used in the census questionnaire. The council makes the supposition that the high difference reported between males and females is due to the "frequently racist publicity in media and due racial prejudices in Mexico's society which shuns dark skin in favor of light skin, thus making women think that white is beautiful," the report also states that men do not suffer this problem and thus have no problem recognizing their real skin color.[28] However, a subsequent question in the same survey contradicts said supposition, as it asks Mexicans to evaluate, from 0 to 10 how comfortable they are with their skin color, with the average result being 9.4 out of ten.[29] Furthermore, scientific research proving that human females tend to have lighter skin than their male counterparts exists.[30]

Besides the visual identification of skin color, the same survey included a question on which it asked Mexicans "what would they call their skin color?" while the press report by the CONAPRED remarks that six out of ten people considered themselves to be "moreno" (brunette in English) and only one out of ten considered their skin to be "blanco" (white)[31] the actual questionnaire included as choices other words who are colloquially used to refer to white people in Mexico such as "Güero" (informal for white), "Claro" (clear), "Aperlado" (Pearly) and other words who may or not refer to a white person depending of the case, such as "Quemadito" (Burnt), "Bronceado" (Tanned), "Apiñonado" (Spiced), "Amarillo" (Yellow) and "Canela" (Cinnamon). Further complicating the situation, several words used specifically for brown skin also appear as choices such as "Café" (Brown), "Negro" (Black), "Chocolate" (translation unnecessary), "Oscuro" (Dark), "Prieto" (Very dark) and "Trigueño" (other word for brown).[32] The word "moreno" itself has a very wide definition in Spanish and has no specific racial connotations, being used equally to define light-skinned people with dark hair as to define people of African ancestry.[33]

| Skin Type | Percentage (inegi 2017) |

|---|---|

| A | 0.2% |

| B | 0.5% |

| C | 1.0% |

| D | 3.0% |

| E | 2.7% |

| F | 13.0% |

| G | 30.0% |

| H | 37.4% |

| I | 5.2% |

| J | 4.9% |

| K | 2.1% |

In 2017, Mexico's National Institute of Statistics and Geography published the Intergenerational Social Mobility Module (MMSI),[9] composed of a series of nationwide surveys focused on education, generational economic mobility and ethnicity, it's particularly notorious for giving Mexicans the possibility to identify with a race (the aviable choices being "Indigenous", "Mestizo", "White" and "Other"). While the results of questions directly related to race were published, the percentage of Mexicans who identified with each race was not. Also included in the survey was a color palette (the same as the one used in the PERLA project: composed of 11 different tones with "A" being the darkest and "K" being the lightest) so a person could chose what color the skin of his/her face was. The percentage of Mexicans that identified with each skin color was not included in the main MMSI document but unlike racial composotion it was made public through other official publications.[10] Unlike the survey published by the CONAPRED in 2010, the results of this study received enormous media coverage, with media outlets bringing to Mexico's mainstream opinion circles concepts such as systemic racism, white privilege and colonialism.[12][34] as the study concluded that Mexicans with medium ("F" tone) and darker skin tones have in average lower profile occupations than Mexicans with lighter skin tones. Also stated is that Mexicans with lighter skin tones (lighter than "F") have higher levels of academic achievement.[9] The study also points out that out of the 4 racial categories used in the study, that of Indigenous Mexicans is the one that shows the highest percentage of positive social mobility (meaning that a person is better off than his/her parents were) while White Mexicans are the ones who have the lowest positive social mobility.[9] Said section of the study, alongside the ones who did not address race, received almost no media coverage.

In 2018, the new edition of the ENADIS was published, this time being a joint effort by the CONAPRED and the INEGI with collaboration of the UNAM, the CONACyT and the CNDH.[35] Like it's 2010 antecesor, it surveyed Mexican citizens about topics related to discrimination and collected data related to phenotype and ethnic self-identification. It concluded that Mexico is still a fairly conservative country regarding minority groups such as religious minorities, ethnic minorities, foreigners, members of the LGBT collective etc. albeit there's pronounced regional differences, with states in the south-center regions of Mexico having in general notoriously higher discrimination rates towards the aforementioned social groups than the ones states in the western-north regions have.[35] For the collecting of data related to skin color the palette used was again the PERLA one. This time 11% of Mexicans were reported to have "dark skin tones (A-E)" 59% to have "medium skin tones (F-G)" and 29% to have "light skin tones (H-K)".[35] The reason for the huge difference regarding the reported percentages of Mexicans with light skin (around 18% lower) and medium skin (around 16% higher) in the relation to previous nationwide surveys lies in the fact that the ENADIS 2017 prioritized the surveying of Mexicans from "vulnerable groups" which among other measures meant that states with known high numbers of people from said groups surveyed more people.[36]

Independent field studies have been made in attempt to quantify the number of European Mexicans living in modern Mexico, using blond hair as reference to classify a Mexican as white, the Metropolitan Autonomous University of Mexico calculated their percentage at 23%, the study explicitly states that red-haired people were not classified as white but as "other."[18] A study made by the University College London which included multiple Latin American countries and was made with collaboration of each country's anthropology and genetics institutes reported that the frequency of blond hair and light eyes in Mexicans was of 18.5% and 28.5% respectively,[20] making Mexico the country with the second-highest frequency of blond hair in the study. Despite this, the European ancestry estimated for Mexicans is also the second-lowest of all countries included, the reason behind such discrepancy may lie in the fact that the samples used in Mexico's case were highly disproportional, as the northern and western regions of Mexico contain 45% of Mexico's population, but no more than 10% of the samples used in the study came from the states located in these regions. For the most part, the rest of the samples hailed from Mexico City and southern Mexican states.[37]

In 2010 a study published by the American Sociological Association explored social inequalities between Mexicans of different skin colors. The field research consisted of three waves of interviews on different Mexican states during the timespan of a year, people surveyed where split on 3 different groups: "White," "Light brown" and "Dark brown," with the classification being up to the criteria of the interviewers who is claimed, were trained for the task. It is stated that, in order to obtain stable results and prevent inconsistencies regarding who belongs to a given category, additional phenotypical traits besides the respondents' skin color were considered, such as the presence of blond hair in the case of individuals that were to be classified in the "White" category, because "unlike skin color, hair color does not darken with exposure to sunlight." It is indeed claimed within the study that out of the three color categories used, the percentages obtained for the "White" one through the three waves of interviews were the most consistent. According to the results of the study, the average percentage of Mexicans who were classified as "White" per the presence of blond hair was 18.8%, with the Northeast and Northwest regions having the highest frequencies at 23.9% and 22.3% respectively, followed by the Center region with 21.3%, the Center-West region with 18.4% and finally the South region with 11.9%. The study makes the acclaration that Mexico city (Center region) as well as rural areas of the states of Oaxaca, Chiapas (both from the south region) and Jalisco (Center-West region) were oversampled.[19]

The following tables (the first from a study published in 2002[38] and the second from a study published in 2018[39]) show the frequencies of different blood types in various Mexican cities and states, as Mexico's Amerindian/Indigenous population exclusively exhibits the "O" blood type, the presence of other blood groups can give an approximate idea of the amount of foreign influence there is in each state that has been analyzed. The results of this studies however, shouldn't be taken as exact, literal estimations for the percentages of different ethnic groups that there may be in Mexico (I.E. A+B blood groups = percentage of White Mexicans) for reasons such as the fact that a Mestizo Mexican can have "A", "B" etc. blood types or the fact that the "O" blood type does exist in Europe, with it having a frequency of 44% in Spain for example.[40]

| City | State | O (%) | A (%) | B (%) | AB (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Paz | Baja California Sur | 58.49% | 31.4% | 8.40% | 1.71% |

| Guadalajara | Jalisco | 57.2% | 31.2% | 9.7% | 1.9% |

| Gómez Palacio | Durango | 57.99% | 29.17% | 10.76% | 2.08% |

| Ciudad Victoria | Tamaulipas | 63.6% | 27.3% | 7.4% | 1.7% |

| Monterrey | Nuevo Leon | 63.1% | 26.5% | 9.0% | 1.4% |

| Veracruz | Veracruz | 64.2% | 25.7% | 8.1% | 2.0% |

| Saltillo | Coahuila | 64.2% | 24.9% | 9.7% | 1.2% |

| Saladero | Veracruz | 60.5% | 28.6% | 10.9% | 0.0% |

| Torreón | Coahuila | 66.35% | 24.47% | 8.3% | 0.88% |

| Mexico City | Mexico City | 67.7% | 23.4% | 7.2% | 1.7% |

| Durango | Durango | 55.1% | 38.6% | 6.3% | 0.0% |

| Ciudad del Carmen | Campeche | 69.7% | 22.0% | 6.4% | 1.8% |

| Mérida | Yucatan | 67.5% | 21.1% | 10.5% | 0.9% |

| Leon | Guanajuato | 65.3% | 24.7% | 6.0% | 4.0% |

| Zacatecas | Zacatecas | 61.9% | 22.2% | 13.5% | 2.4% |

| Tlaxcala | Tlaxcala | 71.7% | 19.6% | 6.5% | 2.2% |

| Puebla | Puebla | 72.3% | 19.5% | 7.4% | 0.8% |

| Oaxaca | Oaxaca | 71.8% | 20.5% | 7.7% | 0.0% |

| Paraiso | Tabasco | 75.8% | 14.9% | 9.3% | 0.0% |

| Total | ~~ | 65.0% | 25.0% | 8.6% | 1.4% |

| State | O (%) | A (%) | B (%) | AB (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baja California Norte | 60.25% | 28.79% | 9.03% | 1.92% |

| Sonora | 58.58% | 30.48% | 9.11% | 1.84% |

| Sinaloa | 56.46% | 32.93% | 8.56% | 2.05% |

| Durango | 59.29% | 26.89% | 11.33% | 2.50% |

| Coahuila | 66.17% | 23.49% | 9.01% | 1.33% |

| Nuevo Leon | 62.43% | 25.62% | 10.10% | 1.85% |

| Nayarit | 59.20% | 29.62% | 9.32% | 1.85% |

| Jalisco | 57.85% | 29.95% | 9.78% | 2.42% |

| Michoacan | 60.25% | 29.51% | 9.04% | 2.44% |

| Puebla | 74.36% | 18.73% | 6.05% | 0.87% |

| Veracruz | 67.82% | 21.90% | 8.94% | 1.34% |

| San Luis Potosi | 67.47% | 24.27% | 7.28% | 0.97% |

| Aguascalientes | 61.42% | 26.25% | 10.28% | 2.05% |

| Guanajuato | 61.98% | 26.83% | 9.33% | 1.85% |

| Queretaro | 65.71% | 23.60% | 9.40% | 1.29% |

| State of Mexico | 70.68% | 21.11% | 7.18% | 1.04% |

| Mexico City | 66.72% | 23.70% | 8.04% | 1.54% |

| Total | 61.82% | 27.43% | 8.93% | 1.81% |

Both studies find similar trends regarding the distribution of different blood groups, with foreign blood groups being more common in the North and Western regions of Mexico, which is congruent with the findings of genetic studies that have been made in the country through the years. It is also observed that "A" and "B" blood groups are more common among younger volunteers whereas "AB" and "O" are more common in older ones. The total number of analyzed samples in the 2018 study was 271,164.

A study performed in hospitals of Mexico City reported that in average 51.8% of Mexican newborns presented the congenital skin birthmark known as the Mongolian spot whilst it was absent in 48.2% of the analyzed babies.[41] The Mongolian spot appears with a very high frequency (85-95%) in Asian, Native American and African children.[42] The skin lesion reportedly almost always appears on South American[43] and Mexican children who are racially Mestizos[44] while having a very low frequency (5-10%) in Caucasian children.[45] According to the Mexican Social Security Institute (shortened as IMSS) nationwide, around half of Mexican babies have the Mongolian spot.[46]

According to the 2010 US Census, 52.8% of Mexican Americans (approximately 16,794,111 people) self-identified as being White.[47]

Genetic research

Genetic research in the Mexican population is numerous and has yielded a myriad of different results, it is not rare that different genetic studies done in the same location vary greatly, clear examples of said variation are the city of Monterrey in the state of Nuevo León, which, depending on the study presents an average European ancestry ranging from 38%[48] to 78%,[49] and Mexico City, whose European admixture ranges from as little as 21%[50] to as high as 70%,[51] reasons behind such variation may include the socioeconomic background of the analyzed samples[51] as well as the criteria to recruit volunteers: some studies only analyze Mexicans who self-identify as Mestizos,[52] others may classify the entire Mexican population as "mestizo",[53] other studies may do both, such as the 2009 genetic study published by the INMEGEN (Mexico's National Institute of Genomic Medicine), which states that 93% of the Mexican population is Mestizo with the remaining population being Amerindian, this particular statement has received considerable media exposure through the years[54][55] to dismay of scientists from the aforementioned institute, who have complained about the study being misinterpreted by the press as it wasn't meant to represent Mexico's population as a whole.[56] According to the methodology of the aforementioned study the institute only recruited people who explicitly self-identified as Mestizos.[57] Finally there are studies which avoid using any racial classification whatsoever, including in them any person who self-identifies as Mexican; these studies are the ones that usually report the highest European admixture for a given location.[58]

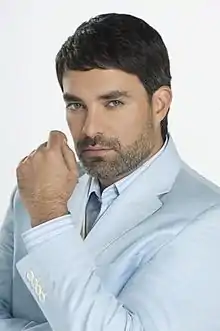

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The Mestizaje ideology, which has blurred the lines of race at an institutional level has also had a significative influence in genetic studies done in Mexico.[56] As the criteria used in studies to determine if a Mexican is Mestizo or indigenous often lies in cultural traits such as the language spoken instead of racial self-identification or a phenotype-based selection there are studies on which populations who are considered to be Indigenous per virtue of the language spoken show a higher degree of European genetic admixture than the one populations considered to be Mestizo report in other studies.[59] The opposite also happens, as there instances on which populations considered to be Mestizo show genetic frequencies very similar to continental European peoples in the case of Mestizos from the state of Durango[60] or to European derived Americans in the case of Mestizos from the state of Jalisco.[61]

Regardless of the criteria used, all the autosomal DNA studies made coincide on there being a significant genetic variation depending of the region analyzed, with southern Mexico having prevalent Amerindian and small but higher than average African genetic contributions, the central region of Mexico shows a balance between Amerindian and European components,[62] with the later gradually increasing as one travels northwards and westwards, where European ancestry becomes the majority of the genetic contribution[63] up until cities located in the Mexico–United States border, where studies suggest there is a significant resurgence of Amerindian and African admixture.[64]

To date, no genetic research focusing on Mexicans of complete or predominant European ancestry has been made.

A 2014 publication summarizing population genetics research in Mexico, including three nationwide surveys and several region-specific surveys, found that in the studies done to date, counting only studies that looked at the ancestry of both parents (autosomal ancestry): "Amerindian ancestry is most prevalent (51% to 56%) in the three general estimates (initially published by the INMEGEN in 2009), followed by European ancestry (40% to 45%); the African share represents only 2% to 5%. In Mexico City, the European contribution was estimated as 21% to 32% in six of the seven reports, with the anomalous value of 57% obtained in a single sample of 19 subjects, albeit said percentage can't really be called anomalous, as autosomal studies that obtain percentages of European ancestry of 51%,[65] 52%,[58] 70%[51] and 52%,[66] exists, (with the last one being for Mexico's central region as a whole) but were not included on this publication for unspecified reasons. According to the studies that were included, European ancestry is most prevalent in the north (Chihuahua, 50%; Sonora, 62%; Nuevo León, 55%), but in a recent sample from Nuevo León and elsewhere in the country, Amerindian ancestry is dominant."[67]

A 2006 nationwide autosomal study, the first ever conducted by Mexico's National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN), which included the states of Guerrero, Oaxaca, Veracruz, Yucatan, Zacatecas and Sonora reported that self-identified Mestizo Mexicans are 58.96% European, 35.05% "Asian" (primarily Amerindian), and 5.03% Other.[52]

An autosomal ancestry study performed on Mexico city reported that the European ancestry of Mexicans was 52% with the rest being Amerindian and a small African contribution, additionally maternal ancestry was analyzed, with 47% being of European origin. The only criteria for sample selection was that the volunteers self-identified as Mexicans.[58]

Establishment of Europeans in Mexico

The presence of Europeans in what is nowadays known as Mexico dates back to the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in the early 16th century[68][69] by Hernán Cortés, his troops and a number of indigenous city states who were tributaries and rivals of the Aztecs, such as the Totonacs, the Tlaxcaltecas and Texcocans among others. There are stories about Moctezuma taking Cortés to be the return of the God Quetzalcoatl due to his light skin and light-colored hair and eyes, which had never been seen before by the people of Mesoamerica. However, this has been disputed. After years of war the coalition led by Cortés finally managed to conquer the Aztec Empire which would result on the foundation of the Viceroyalty of New Spain and while this new state granted a series of privileges to the members of the allied indigenous tribes such as nobiliary titles and swathes of land, the Spanish held the most political and economic power.[70][68][71] The small number of Spaniards who inhabited the new kingdom would soon be complemented by a steady migration flow of Spanish people,[71] as it was the interest of the Spanish crown to Hispanicize and Christianize the region given that Indigenous peoples and their customs were considered uncivilized, thus the Spanish language and culture were imposed and indigenous ones suppressed.[68][72]

The Mexican experience mirrors much of that of the rest of Latin America, as attitudes towards race, including identification, were set by the conquistadors and Spanish who came soon after.[71] Through the colonial period, the Spanish and their descendants, called "criollos" remained outnumbered by the indigenous and "mestizos" or those of mixed Spanish and indigenous parents[68][72] (albeit a person of 7/8 Spanish ancestry and 1/8 or less indigenous ancestry could be considered to be "criollo").[73] To keep power, the Spanish enforced a hierarchical class system in New Spain's society, with those born in Spain (known as Peninsulares) being the most privileged, followed by criollos, then Mestizos, then the indigenous and finally the Africans. Nonetheless the system was not completely rigid and elements such as social class, social relations and who a person descended from did figure into it. However, the notion of "Spanishness" would remain at the top and "Indianness" would be at the bottom, with those mixed being somewhere in the middle. This idea remained officially in force through the rest of the colonial period.[68]

Criollo resentment of the privileges afforded to the Peninsulares was the main reason behind the Mexican War of Independence. When the war ended in 1821, the new Mexican government expelled the peninsulares (approximately 10,000 – 20,000 people) in the 1820s and 1830s which at a degree, kept the European ethnicity from growing as a percentage;[72] this expulsion however, did not lead to any permanent ban on European immigrants, even from Spain.[69] Independence did not do away with economic and social privilege based on race as the Criollos took over those of Spanish birth. A division between "Spanish" and "indigenous" remained with Criollos distinguishing themselves from the rest of society as the guardians of Spanish culture as well as the Catholic religion.[74] Due to the abolition of the caste system the division, however, became more about money and social class and less about biological differences which widened the possibilities of social mobility for Mestizo and Indigenous Mexicans. For this reason many of the political and cultural struggles of the latter 19th and early 20th centuries would be between the Criollos and the Mestizos.[72]

According to Mexico's first ever racial census published in 1793, the Eurodescendant population was between 18%-22% of the population (with Mestizos being 21%-25% and Amerindians being 51%-61%)[75] but by 1921, when the second nationwide census that considered a person's race took place, only 9% of the population self identified as being of European descent, with 59% being Mestizo and 29% being Amerindian. While for a long time the 1921 census' results were taken as fact, with international publications such as The World Factbook and Encyclopædia Britannica using them as a reference to estimate Mexico's racial composition up to this day,[1][2] in recent time Mexican academics have subjected them to scrutiny, claiming that such a drastic alteration on demographic trends is not possible and cite, among other statistics the relatively low frequency of marriages between people of different continental ancestries.[76][17] The authors claim that the Mexican society went through a "more cultural than biological mestizaje process" sponsored by the state which resulted on the inflation of the percentage of the Mestizo Mexican group at the expense of the identity of other races. It is important to note that the Mexican academics who question the census numbers are doing so primarily on behalf of Indigenous peoples, who they claim have been forcefully classified as Mestizos but state or suggest nonetheless, that the same thing has happened to European Mexicans.[77] In the early 1890s, Northern Italian immigrants were brought from the Veneto area to Mexico to whiten the population.[78]

In today's society

The lack of a clear defining line between white and mixed race Mexicans has made the concept of race relatively fluid, with descent being more of a determining factor than biological traits.[69] Even though there is large variation in phenotypes among Mexicans, European looks are still strongly preferred in Mexican society, with lighter skin receiving more positive attention as it is associated with higher social class, power, money and modernity.[69][71] In contrast, Indigenous ancestry is often associated with having an inferior social class as well as lower levels of education.[68] These distinctions are strongest in Mexico City, where the most powerful of the country's elite are located.[69]

Since the end of the Mexican Revolution, the official identity promoted by the government for non-indigenous Mexicans has been the Mestizo one (a mix of European and indigenous culture and heritage). Installed with the original intent of eliminating divisions and creating a unified identity that would allow Mexico to modernize and integrate into the international community,[69] the Mestizo identity has not been able to achieve its goal. The reason for this is speculated to be the identity's own internal contradictions, as it includes in the same theoretical race people who, in daily interactions, do not consider each other to be of the same race and have little in common biologically, with some of them being entirely Indigenous, others entirely European and including also Africans and Asians.[25] Today, there is no definitive census that quantifies Mexico's white population, with estimations from different publications varying greatly, ranging from just 9% of the total[1][81] to 47%,[3][4] with this figure being based on phenotypical traits instead of self-identification of ancestry.

Despite what the mestizaje discourse asserts, Mexico is a country where Eurodescendants are not a minority, neither a clear majority but rather exist on an even amount in relation to Mestizos.[82] Because of this even though the Mexican government didn't used racial terms related to European or white people officially for almost a century (retaking this practice until after 2010), the concepts of "white people" (known as güeros or blancos in Mexican Spanish) and of "being white" didn't disappear [83] and are still present on everyday Mexican culture: different idioms of race are used in Mexico's society that serve as mediating terms between racial groups. It is not strange to see street vendors calling a potential costumer "Güero" or "güerito", sometimes even when the person is not light-skinned. In this instance it is used to initiate a kind of familiarity, but in cases where social/racial tensions are relatively high, it can have the opposite effect.[69]

This widespread preference that Mexicans, even those who are of predominant indigenous ancestry show to European cultures and values over Indigenous ones has come to be known as malinchismo which means to identify or favor a North American or European culture over the native one. It derives from La Malinche, the native interpreter who allied with Hernán Cortés during the Conquest. The story is still an important social imagery for Mexicans. Examples of practices considered as malinchismo in modern Mexico include Mexican parents choosing English given names for their kids, due to the desire to be associated with the United States.[68]

European immigration to Mexico

Mexico's European heritage is strongly associated to Spanish settlement during the colonial period, not having witnessed the same scale of mass recent-immigration as other New World countries such as the United States, Brazil and Argentina.[69] However, this ruling is less blanket fact and more of a consequence due to Mexico's enormous population. Regardless, Mexico ranks 3rd behind Brazil and Argentina for European immigration in Latin America with its culture owing a great deal to the significant German, Polish, and French populations. White Mexicans rather, descend of a considerably ethnocentrist group of Spanish people who, beginning with the arrival and establishment of the conquistadors to then be supplemented with clerics, workers, academics etc. immigrated to what today is Mexico. The criollos (as people born in the colonies to Spanish parents were called until the beginning of the 20th century)[71] would favor for marriage other Spanish immigrants even if they were of a less privileged economic class than them, as to preserve the Spanish lineage and customs was seen as the top priority. Once Mexico achieved its independence and immigration from European countries other than Spain became accepted, the criollos did the same, and sought to assimilate the new European immigrants into the overwhelmingly Spanish-origin white Mexican population, as the yearly immigration rate of Europeans to Mexico never exceeded 2% in relation to the country's total population, assimilation of the new immigrants was easy and Mexican hyphenated identities never appeared.[74]

Another way on which European immigration to Mexico differed from that of other New World countries was on the profile of the needed immigrant. As New Spain's main economic activities were not related to agriculture (and the manpower for it was already supplied by the converted indigenous population)the country didn't enforce any sort of programs that would make it an attractive destination for European farmers. Much more important to the economy was mining and miners came from Europe, in particular from Cornwall, U.K. and even today parts of Mineral del Monte and Pachuca maintain strong links to both their British heritage and with the United Kingdom. There was also strong demand for people with specialized skills in fields such as geology, metallurgy, commerce, law, medicine etc. As stories of professional immigrants amassing huge wealth in a pair of years were commonly heard, New Spain became very attractive only for Europeans who filled these profiles and their families, which in the end resulted on the country getting relatively less European immigration,[72][74] is also because of the aforementioned reasons that the majority of Spanish immigrants who arrived to the country were from the northern regions of Spain, mainly Cantabria, Navarra, Galicia and the Basque Country.[84] After the war of independence, the country's almost completely European elite would associate civilization with European characteristics, blaming the country's indigenous heritage for its inability to keep up with the economic development of the rest of the world. This led to active efforts to encourage the arrival of additional European immigrants.[69]

One of these efforts was the dispossession of large tracts of land from the Catholic Church with the aim of selling them to immigrants and others who would develop them. However, this did not have the desired effect mostly because of political instability. The Porfirio Díaz regime of the decades before the Mexican Revolution tried again, and expressly desired European immigration to promote modernization, instill Protestant work ethics and buttress what remained of Mexico's North from further U.S. expansionism. Díaz also expressed a desire to "whiten" Mexico's heavily racially mixed population, although this had more to do with culture than with biological traits. However, the Díaz regime knew it had to be cautious, as previously large concentrations of Americans in Texas, would eventually lead to the secession of that territory.[72][74] This precautions meant that the government had more success luring investors than permanent residents, even in rural areas despite government programs. No more than forty foreign farming colonies were ever formed during this time and of these only a few Italian and German ones survived.[74]

By the mid-19th century, between Europeans and ethnically European Americans and Canadians, there were only 30,000 to 40,000 European immigrants in Mexico, compared to an overall population of over eight million, but their impact was strongly felt as they came to dominate the textile industry and various areas of commerce and industry, incentivating the industrialization of the country. Many of these immigrants were not really immigrants at all, but rather "trade conquistadors" who remained in Mexico only long enough to make their fortunes to return to their home countries to retire. This led Diaz to nationalize industries dominated by foreigners such as trains, which would cause many trade conquistadors to leave.[74] In January 1883, the Government signed a law to promote the Irish, German and French immigration to Mexico, this time there were less restrictions, resulting in the arrival of relatively more conventional immigrants and their families.[85] Up to 1914, 10,000 French settled in Mexico,[86] alongside other 100,000 Europeans.[86] Despite being the most violent conflict in Mexico's history, the Mexican Revolution did not discourage European immigration nor scared away white Mexicans, who, for concentrating in urban areas were largely unaffected by it and thought of it as a conflict pertinent only to rural people.[74] Later on, bellic conflicts in Europe during the 1930s and 1940s such as the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War caused additional waves of European immigration to the country.[87]

By the end of the Second World War, Americans, British, French, Germans and Spanish were the most conspicuous Europeans in Mexico but their presence was limited to urban areas, especially Mexico City, living in enclaves and involved in business. These European immigrants would quickly adapt to the Mexican attitude that "whiter was better" and keep themselves separate from the non-European population of the host country. This and their status as foreigners offered them considerable social and economic advantages, blunting any inclination to assimilate. There was little incentive to integrate with the general Mexican population and when they did, it was limited to the criollo upper class, failing to produce the "whitening" effect desired. For this reason, one can find non–Spanish surnames among Mexico's elite, especially in Mexico City.[72][74]

However, even in the cases when generalized mixing did occur, such as with the Cornish miners in Hidalgo state around Pachuca and Real de Monte, their cultural influence remains strong. In these areas, English style houses can be found, the signature dish is the "paste" a variation of the Cornish pasty[88] and they ended up introducing football (soccer) to Mexico.[89] In the early 20th century, a group of about 100 Russian immigrants, mostly Pryguny and some Molokane and Cossacks came to live in area near Ensenada, Baja California. The main colony is in the Valle de Guadalupe and locally known as the Colonia Rusa near the town of Francisco Zarco. Other smaller colonies include San Antonio, Mision del Orno and Punta Banda. There are an estimated 1,000 descendants of these immigrants in Mexico, nearly all of whom have intermarried. The original settlements are now under the preservation of the Mexican government and have become tourist attractions.[90]

Legal vestiges of attempts to "whiten" the population ended with the 1947 "Ley General de Población" along with the blurring of the lines between most of Mexico immigrant colonies and the general population. This blurring was hastened by the rise of a Mexican middle class, who enrolled their children in schools for foreigners and foreign organizations such as the German Club having a majority of Mexican members. However, this assimilation still has been mostly limited to Mexico's white peoples. Mass culture promoted the Spanish language and most other European languages have declined and almost disappeared. Restrictive immigration policies since the 1970s have further pushed the assimilation process. Despite all of the aforementioned pressure, as of 2013 Mexico is the country with most international immigrants in the world.[91] Since 2000, Mexico's economic growth has increased international migration to the country, including people of European descent who leave their countries (particularly France and Spain) in the search of better work opportunities. People from the United States have moved too, now making up more than three-quarters of Mexico's roughly one million documented foreigners, up from around two-thirds in 2000. Nowadays, more people originally from United States have been added to the population of Mexico than Mexicans have been added to the population of the United States, according to government data in both nations.[92]

Examples of White ethnic groups in Mexico

European immigration to Mexico is not uncommon with many European or European derived ethnic groups responsible for shaping modern Mexican culture. Besides colonial Iberian influences, many other European and/or white communities thrived in Mexico's history such as the Spanish, Polish and French, with the German Mexican community especially dominant on modern culture, once named as “la tercera raza” or “the third race”.[93] Mexico's northwest-pacific region (particularly Sinaloa, Sonora, and the Baja California Peninsula) experienced major surges of Northern Spanish immigration in the late 19th and early 20th century, specifically from Asturias and Galicia (Spain). Most of Latin America's colonial and industrial era Spanish immigration originates from Southern Spain and the Canary Islands, thus this regional enclave of Northern Spaniards is exceptional and remains the biggest diaspora of Asturias and Galicians by heritage in the Americas.[94] This region also experienced concentrated waves of modern European immigration during the 20th century such as Italian and French, and the culture of the region reflects its lack of indigenous admixture. European rooted holidays like Saints days, Carnival as well as gastronomy such as bread, cheese, and wine production remain unique to the region.[95]

One of the few Porfirian-era European settlements to survive to this day is centered on the small town of Chipilo in the state of Puebla. They are the descendants of about 500 Venetian refugee immigrants which came over in the 1880s, keeping their Venetian-derived dialect and distinct ethnic identity, even though many have intermarried with other Mexicans. Many still farm and raise livestock but economic changes have pushed many into industry.[96]

During the Mexican Revolution, Álvaro Obregón invited a group of German-speaking Mennonites in Canada to resettle in Chihuahua state. By the late 1920s, almost 10,000 had arrived from both Canada and Europe.[74][97] Today, Mexico accounts for about 42% of all Mennonites in Latin America with 115,000 practicing Mennonites accounted for.[71] Mennonites in the country especially stand out within their rural surroundings because of their traditional clothing, Plautdietsch language, light skin, hair and eyes. They own their own businesses in various communities in Chihuahua, and account for about half of the state's farm economy, standing out in cheese production.[97]

Immigration was restricted by governments after Diaz's but never stopped entirely during the 20th century. Between 1937 and 1948, more than 18,000 Spanish Republicans arrived as refugees from the Nationalists and Francoist Spain. Their reception by the Mexican criollo elite was mixed but they manage to experience success as most of these newcomers were educated as scholars and artists. This group founded the Colegio de Mexico, one of the country's top academic institutions. Despite attempts to assimilate these immigrant groups, especially the country's already existing German population during World War II, they remain mostly separate to this day.[74]

Due to the 2008 Financial Crisis and the resulting economic decline and high unemployment in Spain, many Spaniards have been emigrating to Mexico to seek new opportunities.[98] For example, during the last quarter of 2012, a number of 7,630 work permits were granted to Spaniards.[99] Other Southern Europeans joined the Spaniards in the 2010s by finding better work opportunities in Mexico with thousands of Italians, Portuguese, French and Greeks finding professional opportunities along with the Spaniards in Mexico.

Sixty-seven percent of Latin America's English-speaking population lives in Mexico.[71] Most of these are American nationals, with an influx of people from the U.S. coming to live in Mexico since the 1930s, becoming the largest group of foreigners in the country since then. However, most Americans in Mexico are not immigrants in the traditional sense, as they are there living as retirees or otherwise do not consider themselves permanent residents.[74][100]

Official censuses

Historically, population studies and censuses have never been up to the standards that a population as diverse and numerous such as Mexico's require: the first racial census was made in 1793, being also Mexico's (then known as New Spain) first ever nationwide population census, of it, only part of the original datasets survive, thus most of what is known of it comes from essays made by researchers who back in the day used the census' findings as reference for their own works. More than a century would pass until the Mexican government conducted a new racial census in 1921 (some sources assert that the census of 1895 included a comprehensive racial classification, however according to the historic archives of Mexico's National Institute of Statistics that was not the case).[101] While the 1921 census was the last time the Mexican government conducted a census that included a comprehensive racial classification, in recent time it has conducted nationwide surveys to quantify most of the ethnic groups who inhabit the country as well as the social dynamics and inequalities between them.

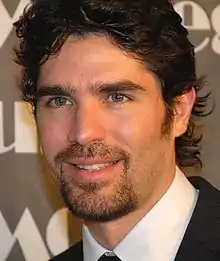

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

1793 census

.svg.png.webp)

Also known as the "Revillagigedo census" due to its creation being ordered by the Count of the same name, this census was Mexico's (then known as the Viceroyalty of New Spain) first ever nationwide population census. Most of its original datasets have reportedly been lost; thus most of what is known about it nowadays comes from essays and field investigations made by academics who had access to the census data and used it as reference for their works such as Prussian geographer Alexander von Humboldt. Each author gives different estimations for each racial group in the country, although they don't vary much, with Europeans ranging from 18% to 22% of New Spain's population, Mestizos ranging from 21% to 25%, Indians ranging from 51% to 61% and Africans being between 6,000 and 10,000, The estimations given for the total population range from 3,799,561 to 6,122,354. It is concluded then, that across nearly three centuries of colonization, the population growth trends of whites and mestizos were even, while the total percentage of the indigenous population decreased at a rate of 13%-17% per century. The authors assert that rather than whites and mestizos having higher birthrates, the reason for the indigenous population's numbers decreasing lies on them suffering of higher mortality rates, due living in remote locations rather than on cities and towns founded by the Spanish colonists or being at war with them. It is also for these reasons that the number of Indigenous Mexicans presents the greater variation range between publications, as in cases their numbers in a given location were estimated rather than counted, leading to possible overestimations in some provinces and possible underestimations in others.[75]

| Intendecy/territory | European population (%) | Indigenous population (%) | Mestizo population (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 16.9% | 66.1% | 16.7% |

| Puebla | 10.1% | 74.3% | 15.3% |

| Oaxaca | 06.3% | 88.2% | 05.2% |

| Guanajuato | 25.8% | 44.0% | 29.9% |

| San Luis Potosi | 13.0% | 51.2% | 35.7% |

| Zacatecas | 15.8% | 29.0% | 55.1% |

| Durango | 20.2% | 36.0% | 43.5% |

| Sonora | 28.5% | 44.9% | 26.4% |

| Yucatan | 14.8% | 72.6% | 12.3% |

| Guadalajara | 31.7% | 33.3% | 34.7% |

| Veracruz | 10.4% | 74.0% | 15.2% |

| Valladolid | 27.6% | 42.5% | 29.6% |

| Nuevo Mexico | ~ | 30.8% | 69.0% |

| Vieja California | ~ | 51.7% | 47.9% |

| Nueva California | ~ | 89.9% | 09.8% |

| Coahuila | 30.9% | 28.9% | 40.0% |

| Nuevo Leon | 62.6% | 05.5% | 31.6% |

| Nuevo Santander | 25.8% | 23.3% | 50.8% |

| Texas | 39.7% | 27.3% | 32.4% |

| Tlaxcala | 13.6% | 72.4% | 13.8% |

~Europeans are included within the Mestizo category.

Regardless of the possible imprecisions related to the counting of Indigenous peoples living outside of the colonized areas, the effort that New Spain's authorities put on considering them as subjects is worth mentioning, as censuses made by other colonial or post-colonial countries did not consider American Indians to be citizens/subjects, as example the censuses made by the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata would only count the inhabitants of the colonized settlements.[102] Other example would be the censuses made by the United States, that did not include Indigenous peoples living among the general population until 1860, and indigenous peoples as a whole until 1900.[103]

1921 census

Made right after the consummation of the Mexican revolution, the social context on which this census was made makes it particularly unique, as the government of the time was in the process of rebuilding the country and was looking forward to unite all Mexicans under a single national identity. The 1921 census' final results in regards to race, which assert that 59.3% of the Mexican population self-identified as Mestizo, 29.1% as Indigenous and only 9.8% as White were then essential to cement the "mestizaje" ideology (that asserts that the Mexican population as a whole is product of the admixture of all races) which shaped Mexican identity and culture through the 20th century and remain prominent nowadays, with extraofficial international publications such as The World Factbook and Encyclopædia Britannica using them as a reference to estimate Mexico's racial composition up to this day.[1][2]

Nonetheless, in recent time the census' results have been subjected to scrutiny by historians, academics and social activists alike, who assert that such drastic alterations on demographic trends with respect to the 1793 census are not possible and cite, among other statistics the relatively low frequency of marriages between people of different continental ancestries in colonial and early independent Mexico.[76][17] It is claimed that the "mestizaje" process sponsored by the state was more "cultural than biological" which resulted on the numbers of the Mestizo Mexican group being inflated at the expense of the identity of other races.[77] Controversies aside, this census constituted the last time the Mexican Government conducted a comprehensive racial census with the breakdown by states being the following (foreigners and people who answered "other" not included):[104]

| Federative Units | Mestizo Population (%) | Amerindian Population (%) | White Population (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aguascalientes | 66.12% | 16.70% | 16.77% |

| Baja California (Distrito Norte) |

72.50% | 07.72% | 00.35% |

| Baja California (Distrito Sur) |

59.61% | 06.06% | 33.40% |

| Campeche | 41.45% | 43.41% | 14.17% |

| Coahuila | 77.88% | 11.38% | 10.13% |

| Colima | 68.54% | 26.00% | 04.50% |

| Chiapas | 36.27% | 47.64% | 11.82% |

| Chihuahua | 50.09% | 12.76% | 36.33% |

| Durango | 89.85% | 09.99% | 00.01% |

| Guanajuato | 96.33% | 02.96% | 00.54% |

| Guerrero | 54.05% | 43.84% | 02.07% |

| Hidalgo | 51.47% | 39.49% | 08.83% |

| Jalisco | 75.83% | 16.76% | 07.31% |

| Mexico City | 54.78% | 18.75% | 22.79% |

| State of Mexico | 47.71% | 42.13% | 10.02% |

| Michoacan | 70.95% | 21.04% | 06.94% |

| Morelos | 61.24% | 34.93% | 03.59% |

| Nayarit | 73.45% | 20.38% | 05.83% |

| Nuevo Leon | 75.47% | 05.14% | 19.23% |

| Oaxaca | 28.15% | 69.17% | 01.43% |

| Puebla | 39.34% | 54.73% | 05.66% |

| Querétaro | 80.15% | 19.40% | 00.30% |

| Quintana Roo | 42.35% | 20.59% | 15.16% |

| San Luis Potosí | 61.88% | 30.60% | 05.41% |

| Sinaloa | 98.30% | 00.93% | 00.19% |

| Sonora | 41.04% | 14.00% | 42.54% |

| Tabasco | 53.67% | 18.50% | 27.56% |

| Tamaulipas | 69.77% | 13.89% | 13.62% |

| Tlaxcala | 42.44% | 54.70% | 02.53% |

| Veracruz | 50.09% | 36.60% | 10.28% |

| Yucatán | 33.83% | 43.31% | 21.85% |

| Zacatecas | 86.10% | 08.54% | 05.26% |

When the 1921 census's results are compared with the results of Mexico's recent censuses[105] as well as with modern genetic research,[94] high consistence is found in regards to the distribution of Indigenous Mexicans across the country, with states located in south and south-eastern Mexico having both, the highest percentages of population that self-identifies as Indigenous and the highest percentages of Amerindian genetic ancestry. However this is not the case when it comes to European Mexicans, as there are instances on which states that have been shown to have a considerably high European ancestry per scientific research are reported to have very small white populations in the 1921 census, with the most extreme case being that of the state of Durango, where the aforementioned census asserts that only 0.01% of the state's population (33 persons) self-identified as "white" while modern scientific research shows that the population of Durango has similar genetic frequencies to those found on European peoples (with the state's Indigenous population showing almost no foreign admixture either).[60] Various authors theorize that the reason for these inconsistencies may lie in the Mestizo identity promoted by the Mexican government, which reportedly led to people who are not biologically Mestizos to identify as such.[25][106]

Present day

The following table is a compilation of (when possible) official nationwide surveys conducted by the Mexican government who have attempted to quantify different Mexican ethnic groups. Given that for the most part each ethnic group was estimated by different surveys, with different methodologies and years apart rather than on a single comprehensive racial census, some groups could overlap with others and be overestimated or underestimated.

| Race or ethnicity | Population (est.) | Percentage (est.) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous | 26,000,000 | 21.5% | 2015[105] |

| Black | 1,400,000 | 01.2% | 2015[105] |

| White | 56,000,000 | 47.0% | 2010[3][4][11] |

| Foreigners residing in Mexico (of any race) | 1,010,000 | <1.0% | 2015[107] |

| East Asian | 1,000,000 | <1.0% | 2010[108] |

| Middle Eastern | 400,000 | <1.0% | 2010[109] |

| Jewish | 68,000 | <1.0% | 2010[110] |

| Muslim | 4,000 | <1.0% | 2015[111] |

| Unclassified (most likely Mestizos) | 37,300,000 | 30.0% | - |

| Total | 123,500,000 | 100% | 2017[112] |

Of all the ethnic groups that have been surveyed, Mestizos are notably absent, which is likely due to the label's fluid and subjective definition, which complicates its precise quantification. However, it can be safely assumed that Mestizos make up at least the remaining 30% unassessed percentage of Mexico's population with possibilities of increasing if the methodologies of the extant surveys are considered. As example the 2015 intercensal survey considered as Indigenous Mexicans and Afro-Mexicans altogether individuals who self-identified as "part Indigenous" or "part African" thus, said people technically would be Mestizos. Similarly, White Mexicans were quantified based on physical traits/appearance, thus technically a Mestizo with a percentage of Indigenous ancestry that was low enough to not affect his/her primarily European phenotype was considered to be white. Finally the remaining ethnicities, for being of a rather low number or being faiths have more permissive classification criteria, therefore a Mestizo could claim to belong to one of them by practicing the faith, or by having an ancestor who belonged to said ethnicities.

Nonetheless, contemporary sociologists and historians agree that, given that the concept of "race" has a psychological foundation rather than a biological one and to society's eyes a Mestizo with a high percentage of European ancestry is considered "white" and a Mestizo with a high percentage of Indigenous ancestry is considered "Indian," a person who identifies with a given ethnic group should be allowed to, even if biologically doesn't completely belong to that group.

See also

References

- "The World Factbook: North America: Mexico: People and Society". The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Retrieved August 23, 2017.

mestizo (Amerindian-Spanish) 62%, predominantly Amerindian 21%, Amerindian 7%, other 10% (mostly European)

- "Mexico: Ethnic groups". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 23, 2017: Ethnic composition (2010): 64.3% mestizo; 15% Mexican white; 10.5% detribalized Amerindian; 7.5% other Amerindian; 1% Arab; 0.5% Mexican black; 1.2% other.

- "21 de Marzo: Día Internacional de la Eliminación de la Discriminación Racial" [March 21: International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico: CONAPRED. 2017. p. 7. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- Encuesta Nacional Sobre Discriminación en Mexico [National Survey on Discrimination in Mexico] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico: CONAPRED. June 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- Sharon R. Ennis, Merarys Ríos-Vargas, Nora G. Albert (May 2011). https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf U.S. Census Bureau, p. 14 (Table 6). Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- "Plautdietsch in Mexico" (PDF). europeanpeoples.imb.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- Includes Poles: Wojciech Tyciński, Krzysztof Sawicki, Departament Współpracy z Polonią MSZ (Warsaw, 2009). "Raport o sytuacji Polonii i Polaków za granicą (The official report on the situation of Poles and Polonia abroad)" (PDF file, direct download 1.44 MB). Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland), pp. 1–466. Retrieved June 14, 2013 (Internet Archive).

- "Resultados del Modulo de Movilidad Social Intergeneracional" Archived July 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, INEGI, 16 June 2017, Retrieved on 30 April 2018.

- "Visión INEGI 2021 Dr. Julio Santaella Castell", INEGI, 03 July 2017, Retrieved on 30 April 2018.

- "DOCUMENTO INFORMATIVO SOBRE DISCRIMINACIÓN RACIAL EN MÉXICO", CONAPRED, Mexico, 21 March 2011, retrieved on 28 April 2017.

- "Por estas razones el color de piel determina las oportunidades de los mexicanos" Archived June 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Huffington post, 26 July 2017, Retrieved on 30 April 2018.

- "Ser Blanco", El Universal, 06 July 2017, Retrieved on 19 June 2018.

- "Comprobado con datos: en México te va mejor si eres blanco", forbes, 07 August 2018, Retrieved on 04 November 2018.

- "¿Sears racista? Causa polémica su nueva campaña de publicidad", Economiahoy.mx, 05 March 2020, Retrieved on 21 July 2020.

- "Critican series mexicanas de Netflix por sólo tener personajes blancos", Tomatazos.com, 23 mayo 2020, consultado el 19 de diciembre de 2020.

- Federico Navarrete (2016). Mexico Racista. Penguin Random house Grupo Editorial Mexico. p. 86. ISBN 9786073143646. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- Ortiz-Hernández, Luis; Compeán-Dardón, Sandra; Verde-Flota, Elizabeth; Flores-Martínez, Maricela Nanet (April 2011). "Racism and mental health among university students in Mexico City". Salud Pública de México. 53 (2): 125–133. doi:10.1590/s0036-36342011000200005. PMID 21537803.

- Villarreal, Andrés (2010). "Stratification by Skin Color in Contemporary Mexico". American Sociological Review. 75 (5): 652–678. doi:10.1177/0003122410378232. JSTOR 20799484. S2CID 145295212.

- "Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals" table 1, Plosgenetics, 25 September 2014. Retrieved on 9 May 2017.

- San Miguel, G. (November 2000). "Ser mestizo en la nueva España a fines del siglo XVIII: Acatzingo, 1792" [To be 'mestizo' in New Spain at the end of the XVIII th century. Acatzingo, 1792]. Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales. Universidad Nacional de Jujuy (in Spanish) (13): 325–342.

- Sherburne Friend Cook; Woodrow Borah (1998). Ensayos sobre historia de la población. México y el Caribe 2. Siglo XXI. p. 223. ISBN 9789682301063. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- "Household Mobility and Persistence in Guadalajara, Mexico: 1811–1842, page 62", fsu org, 8 December 2016. Retrieved on 9 December 2018.

- Wang, Sijia; Ray, Nicolas; Rojas, Winston; Parra, Maria V.; Bedoya, Gabriel; Gallo, Carla; Poletti, Giovanni; Mazzotti, Guido; Hill, Kim; Hurtado, Ana M.; Camrena, Beatriz; Nicolini, Humberto; Klitz, William; Barrantes, Ramiro; Molina, Julio A.; Freimer, Nelson B.; Bortolini, Maria Cátira; Salzano, Francisco M.; Petzl-Erler, Maria L.; Tsuneto, Luiza T.; Dipierri, José E.; Alfaro, Emma L.; Bailliet, Graciela; Bianchi, Nestor O.; Llop, Elena; Rothhammer, Francisco; Excoffier, Laurent; Ruiz-Linares, Andrés (March 21, 2008). "Geographic Patterns of Genome Admixture in Latin American Mestizos". PLOS Genetics. 4 (3): e1000037. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000037. PMC 2265669. PMID 18369456.

- Lizcano Fernández, Francisco (August 2005). "Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI" [Ethnic Composition of the Three Cultural Areas of the American Continent at the Beginning of the XXI Century]. Convergencia (in Spanish). 12 (38): 185–232.

- Howard F. Cline (1963). THE UNITED STATES AND MEXICO. Harvard University Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780674497061. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- "Encuesta Nacional Sobre Discriminación en Mexico" (PDF). Conapred.org.mx. June 2011. pp. 40–43. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- "21 de Marzo Día Internacional de la Eliminación de la Discriminación Racial" In the page 7 of the press release, the council reported that 47% of Mexicans (54% of women and 40% of men) identified with the lightest skin colors used in the census questionary, CONAPRED, Mexico, 21 March. Retrieved on 28 April 2017.

- "Encuesta Nacional Sobre Discriminación en Mexico" pag. 42, "CONAPRED", Mexico DF, June 2011. Retrieved on 28 April 2011.

- Jablonski, Nina G.; Chaplin, George (July 2000). "The evolution of human skin coloration". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (1): 57–106. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0403. PMID 10896812.

- "21 de Marzo Día Internacional de la Eliminación de la Discriminación Racial" pag. 2, CONAPRED, Mexico, 21 March. Retrieved on 28 April 2017.

- "Encuesta Nacional Sobre Discriminación en Mexico" pag. 42, "CONAPRED", Mexico DF, June 2011. Retrieved on 28 April 2017.

- "moreno - Definición", "Wordreference", Retrieved on 29 April 2017.

- "Presenta INEGI estudio que relaciona color de piel con oportunidades", El Universal, l6 June 2017, Retrieved on 30 April 2018.

- "Encuesta Nacional sobre Discriminación 2017", CNDH, 6 August 2018, Retrieved on 10 August 2018.

- "Encuesta Nacional sobre Discriminación 2017. ENADIS. Diseño muestral. 2018" Archived August 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, INEGI, 6 August 2018, Retrieved on 10 August 2018.

- Ruiz-Linares, Andrés; Adhikari, Kaustubh; Acuña-Alonzo, Victor; Quinto-Sanchez, Mirsha; Jaramillo, Claudia; Arias, William; Fuentes, Macarena; Pizarro, María; Everardo, Paola; de Avila, Francisco; Gómez-Valdés, Jorge; León-Mimila, Paola; Hunemeier, Tábita; Ramallo, Virginia; Silva de Cerqueira, Caio C.; Burley, Mari-Wyn; Konca, Esra; de Oliveira, Marcelo Zagonel; Veronez, Mauricio Roberto; Rubio-Codina, Marta; Attanasio, Orazio; Gibbon, Sahra; Ray, Nicolas; Gallo, Carla; Poletti, Giovanni; Rosique, Javier; Schuler-Faccini, Lavinia; Salzano, Francisco M.; Bortolini, Maria-Cátira; Canizales-Quinteros, Samuel; Rothhammer, Francisco; Bedoya, Gabriel; Balding, David; Gonzalez-José, Rolando (September 25, 2014). "Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals". PLOS Genetics. 10 (9): e1004572. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004572. PMC 4177621. PMID 25254375.

- del Peón-Hidalgo, Lorenzo; Pacheco-Cano, Ma Guadalupe; Zavala-Ruiz, Mirna; Madueño-López, Alejandro; García-González, Adolfo (September 2002). "Frecuencias de grupos sanguíneos e incompatibilidades ABO y RhD, en La Paz, Baja California Sur, México" [Blood group frequencies and ABO and RhD incompatibilities in La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico]. Salud Pública de México (in Spanish). 44 (5): 406–412. doi:10.1590/S0036-36342002000500004. PMID 12389483.

- Canizalez-Román, A; Campos-Romero, A; Castro-Sánchez, JA; López-Martínez, MA; Andrade-Muñoz, FJ; Cruz-Zamudio, CK; Ortíz-Espinoza, TG; León-Sicairos, N; Gaudrón Llanos, AM; Velázquez-Román, J; Flores-Villaseñor, H; Muro-Amador, S; Martínez-García, JJ; Alcántar-Fernández, J (2018). "Blood Groups Distribution and Gene Diversity of the ABO and Rh (D) Loci in the Mexican Population". BioMed Research International. 2018: 1925619. doi:10.1155/2018/1925619. PMC 5937518. PMID 29850485.

- "Cruz Roja Espanola/Grupos Sanguineos". Donarsangre.org. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- Magaña, Mario; Valerio, Julia; Mateo, Adriana; Magaña-Lozano, Mario (April 2005). "Alteraciones cutáneas del neonato en dos grupos de población de México" [Skin lesions two cohorts of newborns in Mexico City]. Boletín médico del Hospital Infantil de México (in Spanish). 62 (2): 117–122.

- Miller (1999). Nursing Care of Older Adults: Theory and Practice (3, illustrated ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 90. ISBN 978-0781720762. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- Congenital Dermal Melanocytosis (Mongolian Spot) at eMedicine

- Lawrence C. Parish; Larry E. Millikan, eds. (2012). Global Dermatology: Diagnosis and Management According to Geography, Climate, and Culture. M. Amer, R.A.C. Graham-Brown, S.N. Klaus, J.L. Pace. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 197. ISBN 978-1461226147. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- "About Mongolian Spot". tokyo-med.ac.jp. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- "Tienen manchas mongólicas 50% de bebés", El Universal, January 2012. Retrieved on 3 July 2017.

- "The Hispanic Population: 2010 Census Brief" (PDF). Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- Martinez-Fierro, Margarita L; Beuten, Joke; Leach, Robin J; Parra, Esteban J; Cruz-Lopez, Miguel; Rangel-Villalobos, Hector; Riego-Ruiz, Lina R; Ortiz-Lopez, Rocio; Martinez-Rodriguez, Herminia G; Rojas-Martinez, Augusto (September 2009). "Ancestry informative markers and admixture proportions in northeastern Mexico". Journal of Human Genetics. 54 (9): 504–509. doi:10.1038/jhg.2009.65. PMID 19680268. S2CID 13714976.

- Cerda-Flores, RM; Kshatriya, GK; Barton, SA; Leal-Garza, CH; Garza-Chapa, R; Schull, WJ; Chakraborty, R (June 1991). "Genetic structure of the populations migrating from San Luis Potosi and Zacatecas to Nuevo León in Mexico". Human Biology. 63 (3): 309–27. PMID 2055589.

- Luna-Vazquez, A; Vilchis-Dorantes, G; Paez-Riberos, L.A; Muñoz-Valle, F; González-Martin, A; Rangel-Villalobos, H (September 2003). "Population data of nine STRs of Mexican-Mestizos from Mexico City". Forensic Science International. 136 (1–3): 96–98. doi:10.1016/s0379-0738(03)00254-8. PMID 12969629.

- Lisker, Rubén; Ramírez, Eva; González-Villalpando, Clicerio; Stern, Michael P. (1995). "Racial admixture in a Mestizo population from Mexico City". American Journal of Human Biology. 7 (2): 213–216. doi:10.1002/ajhb.1310070210. PMID 28557218. S2CID 8177392.

- J.K. Estrada; A. Hidalgo-Miranda; I. Silva-Zolezzi; G. Jimenez-Sanchez. "Evaluation of Ancestry and Linkage Disequilibrium Sharing in Admixed Population in Mexico". ASHG. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- Martínez-Cortés, Gabriela; Salazar-Flores, Joel; Gabriela Fernández-Rodríguez, Laura; Rubi-Castellanos, Rodrigo; Rodríguez-Loya, Carmen; Velarde-Félix, Jesús Salvador; Franciso Muñoz-Valle, José; Parra-Rojas, Isela; Rangel-Villalobos, Héctor (September 2012). "Admixture and population structure in Mexican-Mestizos based on paternal lineages". Journal of Human Genetics. 57 (9): 568–574. doi:10.1038/jhg.2012.67. PMID 22832385. S2CID 2876124.

- "Mestizos, 93% de los Mexicanos según estudio", El Universal, 10 March 2009, Retrieved on 26 April 2018.

- "Trazan el mapa genético de la población mestiza mexicana", El Siglo de Durango, 18 August 2009, Retrieved on 26 April 2018.

- Schwartz-Marín, Ernesto; Silva-Zolezzi, Irma (December 2010). ""The Map of the Mexican's Genome": overlapping national identity, and population genomics". Identity in the Information Society. 3 (3): 489–514. doi:10.1007/s12394-010-0074-7. S2CID 144786737.

- Silva-Zolezzi, Irma; Hidalgo-Miranda, Alfredo; Estrada-Gil, Jesus; Fernandez-Lopez, Juan Carlos; Uribe-Figueroa, Laura; Contreras, Alejandra; Balam-Ortiz, Eros; del Bosque-Plata, Laura; Velazquez-Fernandez, David; Lara, Cesar; Goya, Rodrigo; Hernandez-Lemus, Enrique; Davila, Carlos; Barrientos, Eduardo; March, Santiago; Jimenez-Sanchez, Gerardo (May 26, 2009). "Analysis of genomic diversity in Mexican Mestizo populations to develop genomic medicine in Mexico". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (21): 8611–8616. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.8611S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903045106. PMC 2680428. PMID 19433783.

- Price, Alkes L.; Patterson, Nick; Yu, Fuli; Cox, David R.; Waliszewska, Alicja; McDonald, Gavin J.; Tandon, Arti; Schirmer, Christine; Neubauer, Julie; Bedoya, Gabriel; Duque, Constanza; Villegas, Alberto; Bortolini, Maria Catira; Salzano, Francisco M.; Gallo, Carla; Mazzotti, Guido; Tello-Ruiz, Marcela; Riba, Laura; Aguilar-Salinas, Carlos A.; Canizales-Quinteros, Samuel; Menjivar, Marta; Klitz, William; Henderson, Brian; Haiman, Christopher A.; Winkler, Cheryl; Tusie-Luna, Teresa; Ruiz-Linares, Andrés; Reich, David (June 2007). "A Genomewide Admixture Map for Latino Populations". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 80 (6): 1024–1036. doi:10.1086/518313. PMC 1867092. PMID 17503322.

- Buentello-Malo, Leonora; Peñaloza-Espinosa, Rosenda I.; Salamanca-Gómez, Fabio; Cerda-Flores, Ricardo M. (November 2008). "Genetic admixture of eight Mexican indigenous populations: Based on five polymarker, HLA-DQA1, ABO, and RH loci". American Journal of Human Biology. 20 (6): 647–650. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20747. PMID 18770527. S2CID 28766515.

- Sosa-Macías, Martha; Elizondo, Guillermo; Flores-Pérez, Carmen; Flores-Pérez, Janet; Bradley-Alvarez, Francisco; Alanis-Bañuelos, Ruth E.; Lares-Asseff, Ismael (May 2006). "CYP2D6 Genotype and Phenotype in Amerindians of Tepehuano Origin and Mestizos of Durango, Mexico". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 46 (5): 527–536. doi:10.1177/0091270006287586. PMID 16638736. S2CID 41443294.

- Valdez-Velazquez, Laura L; Mendoza-Carrera, Francisco; Perez-Parra, Sandra A; Rodarte-Hurtado, Katia; Sandoval-Ramirez, Lucila; Montoya-Fuentes, Héctor; Quintero-Ramos, Antonio; Delgado-Enciso, Ivan; Montes-Galindo, Daniel A; Gomez-Sandoval, Zeferino; Olivares, Norma; Rivas, Fernando (September 2011). "Renin gene haplotype diversity and linkage disequilibrium in two Mexican and one German population samples". Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 12 (3): 231–237. doi:10.1177/1470320310388440. PMID 21163863. S2CID 26481247.

- Hernández-Gutiérrez, S.; Hernández-Franco, P.; Martínez-Tripp, S.; Ramos-Kuri, M.; Rangel-Villalobos, H. (June 2005). "STR data for 15 loci in a population sample from the central region of Mexico". Forensic Science International. 151 (1): 97–100. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.09.080. PMID 15935948.

- Cerda-Flores, Ricardo M.; Villalobos-Torres, Maria C.; Barrera-Saldaña, Hugo A.; Cortés-Prieto, Lizette M.; Barajas, Leticia O.; Rivas, Fernando; Carracedo, Angel; Zhong, Yixi; Barton, Sara A.; Chakraborty, Ranajit (March 2002). "Genetic admixture in three mexican mestizo populations based on D1S80 and HLA-DQA1 Loci: Genetic Admixture in Mexican Populations". American Journal of Human Biology. 14 (2): 257–263. doi:10.1002/ajhb.10020. PMID 11891937. S2CID 31830084.

- Loya Méndez, Yolanda; Reyes Leal, G; Sánchez González, A; Portillo Reyes, V; Reyes Ruvalcaba, D; Bojórquez Rangel, G (February 1, 2015). "Variantes genotípicas del SNP-19 del gen de la CAPN 10 y su relación con la diabetes mellitus tipo 2 en una población de Ciudad Juárez, México" [SNP-19 genotypic variants of CAPN 10 gene and its relation to diabetes mellitus type 2 in a population of Ciudad Juarez, Mexico]. Nutrición Hospitalaria (in Spanish). 31 (2): 744–750. doi:10.3305/nh.2015.31.2.7729. PMID 25617558.

- Cerda-Flores, RM; Villalobos-Torres, MC; Barrera-Saldaña, HA; Cortés-Prieto, LM; Barajas, LO; Rivas, F; Carracedo, A; Zhong, Y; Barton, SA; Chakraborty, R (2002). "Genetic admixture in three Mexican Mestizo populations based on D1S80 and HLA-DQA1 loci". Am J Hum Biol. 14 (2): 257–63. doi:10.1002/ajhb.10020. PMID 11891937.

- "STR for 15 Loci in a population Sample From the Central Region of Mexico", Pubmed, Retrieved on 21 December 2017.

- Salzano, Francisco Mauro; Sans, Mónica (2014). "Interethnic admixture and the evolution of Latin American populations". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 37 (1 suppl 1): 151–170. doi:10.1590/s1415-47572014000200003. PMC 3983580. PMID 24764751.

- Fortes de Leff, Jacqueline (December 2002). "Racism in Mexico: Cultural Roots and Clinical Interventions1". Family Process. 41 (4): 619–623. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.00619.x. PMID 12613120.

- Alejandra M. Leal Martínez (2011). For The Enjoyment of All:" Cosmopolitan Aspirations, Urban Encounters and Class Boundaries in Mexico City (PhD thesis). Columbia University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences 3453017.

- "Tlaxcala". New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- Francisco Lizcano Fernández (2005). Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI (PDF) (PhD thesis). Centro de Investigación en Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, UAEM, Mexico. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2008. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- Martinez Montiel, Luz María. "Población inmigrante" [Immigrant population]. México Multicultural (in Spanish). Mexico: UNAM. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- Morales, Efraín Castro (January 1983). "Los cuadros de castas de la Nueva España" [Caste cadres of New Spain]. Jahrbuch für Geschichte Lateinamerikas (in Spanish). 20 (1). doi:10.7767/jbla.1983.20.1.671. S2CID 162365969.

- Buchenau, Jurgen (Spring 2001). "Small numbers, great impact: Mexico and its immigrants, 1821–1973". Journal of American Ethnic History. 20 (3): 23–49. PMID 17605190.

- Lerner, Victoria (1968). "Consideraciones sobre la población de la Nueva España (1793-1810): Según Humboldt y Navarro y Noriega" [Considerations on the population of New Spain (1793-1810): According to Humboldt and Navarro and Noriega]. Historia Mexicana (in Spanish). 17 (3): 327–348. JSTOR 25134694.

- Anchondo, Sandra; de Haro, Martha (July 4, 2016). "El mestizaje es un mito, la identidad cultural sí importa" [Miscegenation is a myth, cultural identity does matter] (in Spanish). Mexico: Istmo. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- "Más desindianización que mestizaje. Una relectura de los censos generales de población".

- Nutini, Hugo G. (January 2010). The Mexican Aristocracy: An Expressive Ethnography, 1910–2000. ISBN 9780292773318.

- Andrew Paxman; Claudia Fernández (2013). El tigre: Emilio Azcárraga y su imperio Televisa. Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial México. p. 1. ISBN 978-607-31-1747-0. Retrieved January 13, 2016.