Vietnamese clothing

Việt phục (越服, literally Vietnamese clothing), is the traditional style of clothing worn in Vietnam by the Vietnamese people.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Vietnam |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Literature |

| Sport |

|

History

For centuries, peasant women typically wore a halter top (yếm) underneath a blouse or overcoat, alongside a skirt (váy). It was up to the 1920s in Vietnam's north area in isolated hamlets where skirts were worn.[1] Before Nguyễn dynasty, the cross-collared robe (áo giao lĩnh) was worn popularly.[2][3]

Bách Việt period

The Han Chinese referred to the various non-Han "barbarian" peoples of north Vietnam and southern China as "Yue" (Việt) or Baiyue, saying they possessed common habits like adapting to water, having their hair cropped short and tattooed. [4][5]

Lý dynasty to Trần dynasty (1009–1400)

Vietnamese wore a round neck costume, which made from 4 part of cloths called áo tứ điên.[6] Both men and women could wear that. Besides, there are other types such as: áo giao lĩnh (cross-collared robe). The garments "áo" (áo is for the upper part of body) is over knee length, round neck garments have buttoned, when cross-collared robe tied to the right.

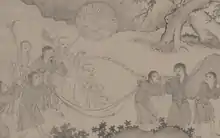

Short hair or shaven head had been popular in Vietnam from the ancient period. Vietnamese men had shaven head or short hair during Trần dynasty.[7] Evidences are in the painting "The Mahasattva Trúc Lâm Coming Out of the Mountains" which drew Trần Nhân Tông and men in Trần dynasty[8] as well as the Chinese encyclopedia "Sancai Tuhui" from 17th century. That conventionality had been popular until the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam.

Trần dynasty clothings as depicted in "The Mahasattva Trúc Lâm Coming Out of the Mountains".

Trần dynasty clothings as depicted in "The Mahasattva Trúc Lâm Coming Out of the Mountains".

Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam

When Han Chinese ruled the Vietnamese in the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam due to the Ming dynasty's conquest during the Ming–Hồ War they imposed the Han Chinese style of men wearing long hair on short haired Vietnamese men. Vietnamese were ordered to stop cutting and instead grow their hair long and switch to Han Chinese clothing in only a month by a Ming official. Ming administrators said their mission was to civilized the unorthodox Vietnamese barbarians.[9] The Ming dynasty only wanted the Vietnamese to wear long hair and to stop teeth blackening so they could have white teeth and long hair like Chinese.[10]

Later Lê dynasty (1428–1789)

The Lê dynasty encouraged the civilians back to the traditional customs: have teeth blackening as well as have hair cut and head shaven. A royal edict was issued by Vietnam in 1474 forbidding Vietnamese from adopting foreign languages, hairstyles and clothes like that of the Lao, Champa or the "Northerners" which referred to the Ming. The edict was recorded in the 1479 Complete Chronicle of Dai Viet of Ngô Sĩ Liên.[11]

Two women and a child in Tonkin around 1700s.

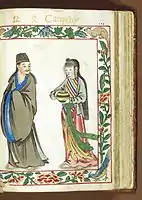

Two women and a child in Tonkin around 1700s. Vietnamese nobleman and wife from Quảng Nam in 1595.

Vietnamese nobleman and wife from Quảng Nam in 1595. Vietnamese nobleman and wife from Hải Môn harbor in 1595.

Vietnamese nobleman and wife from Hải Môn harbor in 1595.

Before 1744, people of both Đàng Ngoài (the north) and Đàng Trong (the south) wore áo giao lĩnh with thường (a kind of long skirt). The Giao Lĩnh dress appeared very early in Vietnamese history, possibly during the first Chinese domination by Eastern Hàn, after Mă Yuán was able to finally defeat the Trưng Sisters’ rebellion. Those of the lower classes would prefer sleeves with reasonable widths or tight sleeves, and of simple colors. This stemmed from its flexibility in work, allowing people to move around with ease.[12] Both male and female had loose long hair.

A servant woman and a mandarin of the Lê dynasty.

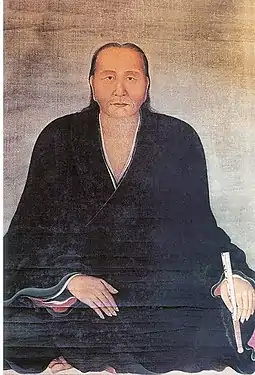

A servant woman and a mandarin of the Lê dynasty. Portrait of Nguyễn Quý Đức in Đàng Ngoài. He was wearing a cross-collared robe (áo giao lĩnh) and had loose long hair.

Portrait of Nguyễn Quý Đức in Đàng Ngoài. He was wearing a cross-collared robe (áo giao lĩnh) and had loose long hair. Portrait of Prince Tôn Thất Hiệp (Nguyễn Phúc Thuần) of Đàng Trong from the 17th century. He wears a cross-collared robe (áo giao lĩnh).

Portrait of Prince Tôn Thất Hiệp (Nguyễn Phúc Thuần) of Đàng Trong from the 17th century. He wears a cross-collared robe (áo giao lĩnh). Portrait of Lady Minh Nhẫn Mrs. Bùi Thị Giác (1738-1805), Thai Binh province of Đàng Ngoài in Revival Lê dynasty.

Portrait of Lady Minh Nhẫn Mrs. Bùi Thị Giác (1738-1805), Thai Binh province of Đàng Ngoài in Revival Lê dynasty.

- Steps to wear Giao Lĩnh (cross-collared robe) as illustrated in the book Weaving a Realm

_1_-_Vietnamese_ancient_costumes_-_Vietnamese_traditional_clothing_-_Weaving_a_Realm.jpg.webp)

_2_-_Vietnamese_ancient_costumes_-_Vietnamese_traditional_clothing_-_Weaving_a_Realm.jpg.webp)

Hoàng Bào (Yellow Robe)

Phan Huy Chú wrote in the Categorized Records of the Institutions of Successive Dynasties (Lịch triều hiến chương loại chí), "Since the Restored Later-Lê era, for grand and formal occasions, (the emperors) always wore Xung Thiên hat and Hoàng Bào robe...". Through many portraits and images of rulers during Míng, Joseon, and more recently, Nguyễn of Vietnam, one could see that this standard existed for a long period of time within a very large region.[12]

According to the book Weaving a Realm, the only artifact of the Lê’s Hoàng Bào was the funeral robe of Emperor Lê Dụ Tông during the Restored Later-Lê period. However, the dragon patterns on this dress had already followed the "dragon–cloud [龍雲大會]" style, a common style of late Míng dynasty. In this period, dragon designs were very large at the chest and back and smaller at the shoulders, with cloud and fire patterns all over the robe. One could see that the pattern style was closer to late Míng than early Míng, therefore Lê Dụ Tông's robe patterns were only specific to an era of the Restored Later-Lê, while the Early Later-Lê possibly still followed the dragon mandala style.[12]

_of_Vietnamese_Emperors_-_Vietnamese_ancient_costumes_-_Vietnamese_traditional_clothing_-_Weaving_a_Realm.png.webp)

In 1744, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát of Đàng Trong (Huế) decreed that both men and women at his court wear trousers and a gown with buttons down the front. That the Nguyen Lords introduced ancient áo dài (áo ngũ thân). The members of the Đàng Trong court (southern court) were thus distinguished from the courtiers of the Trịnh Lords in Đàng Ngoài (Hanoi),[13][3] who wore áo giao lĩnh with long skirts.[14]

- Paintings about Đàng Ngoài

.jpg.webp)

"Giảng học đồ" (講學圖 - Teaching): Đàng Ngoài in 18th century, Hanoi museum of National History;

"Giảng học đồ" (講學圖 - Teaching): Đàng Ngoài in 18th century, Hanoi museum of National History; "Giảng học đồ" (講學圖 - Teaching): Scholars and students wear cross-collared robe (áo giao lĩnh);

"Giảng học đồ" (講學圖 - Teaching): Scholars and students wear cross-collared robe (áo giao lĩnh); "Giảng học đồ" (講學圖 - Teaching): Adults had loose and long hair.

"Giảng học đồ" (講學圖 - Teaching): Adults had loose and long hair.

Nguyễn dynasty (1802–1945)

Áo ngũ thân (ancient áo dài which made of 5 parts of clothes) with standing collar and trousers was forced on Vietnamese people by the Nguyễn dynasty. "Váy đụp" (skirt) was banned.[15] However, it was up to the 1920s in Vietnam's north area in isolated hamlets where skirts were worn.

The Vietnamese had adopted the Chinese political system and culture during the 1,000 years of Chinese rule so they viewed their surrounding neighbors like Khmer Cambodians as barbarians and themselves as a small version of China (the Middle Kingdom).[16] By the Nguyen dynasty the Vietnamese themselves were ordering Cambodian Khmer to adopt Han Chinese culture by ceasing "barbarous" habits like cropping hair and ordering them to grow it long besides making them replace skirts with trousers.[17] Han Chinese Ming dynasty refugees numbering 3,000 came to Vietnam at the end of the Ming dynasty. They opposed the Qing dynasty and were fiercely loyal to the Ming dynasty. Vietnamese women married these Han Chinese refugees since most of them were soldiers and single men. Their descendants became known as Minh Hương and they strongly identified as Chinese despite influence from Vietnanese mothers. They did not wear Manchu hairstyle unlike later Chinese migrants to Vietnam during the Qing dynasty.[18]

Áo giao lĩnh still be used during Nguyễn dynasty. Besides, the Nguyễn dynasty created áo nhật bình, khăn vấn.

Men of Nguyễn dynasty in formal attire

Men of Nguyễn dynasty in formal attire Empress Nam Phương on her wedding day, 1934

Empress Nam Phương on her wedding day, 1934 Empress Nam Phương wearing áo nhật bình and khăn vành dây

Empress Nam Phương wearing áo nhật bình and khăn vành dây Princess Mỹ Lương wearing red áo nhật bình and dark blue khăn vành dây

Princess Mỹ Lương wearing red áo nhật bình and dark blue khăn vành dây

The áo dài was created when tucks which were close fitting and compact were added in the 1920s to this Chinese style. The Chinese clothing in the form of trousers and tunic were mandated by the Vietnamese Nguyen government. The Chinese Ming dynasty, Tang dynasty, and Han dynasty clothing was referred to be adopted by Vietnamese military and bureaucrats by the Nguyen Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát (Nguyen The Tong) from 1744.[3]

- Artifacts of Nguyễn dynasty

19th century Phốc Đầu cap, with ornamented gold Kim Bác Sơn

19th century Phốc Đầu cap, with ornamented gold Kim Bác Sơn Mandarin boots and shoes. Gilded metal, Nguyễn dynasty, 19th-early 20th century[lower-alpha 1]

Mandarin boots and shoes. Gilded metal, Nguyễn dynasty, 19th-early 20th century[lower-alpha 1] Uniforms of students of the imperial academy

Uniforms of students of the imperial academy Court attires of Nguyễn Dynasty

Court attires of Nguyễn Dynasty Ceremonial dress of Marshall Nguyễn Tri Phương[lower-alpha 2]

Ceremonial dress of Marshall Nguyễn Tri Phương[lower-alpha 2]

Examples of garments

- Áo giao lĩnh – cross-collared robe were popular in Lê dynasty and the earlier dynasties.

- Áo tứ thân – a four-piece woman's dress, áo ngũ thân in 5-piece form.

- Yếm – woman's undergarment.

- Áo gấm – formal brocade tunic for government receptions, or áo the for the man in weddings.

- Đinh Tự, Phốc Đầu, the standard conical nón lá and lampshade nón quai thao (Headware)

- Khăn vấn – kind of garment wear on head of Vietnamese people which was popular used from Nguyễn dynasty.

- Áo tràng Phật tử – typically shortened to "áo tràng" it is a robe worn by Upāsaka and Upāsikā in Vietnamese Buddhist temples.[lower-alpha 3]

- Áo dài – the typical Vietnamese formal girl's dress

- Áo bà ba – two-piece ensemble for men and women[19]

- Áo bà ba (black pyjamas), dép lốp (rubber sandals), the rural khăn rằn scarf. (Clothing associated with the Vietnam war)

Twentieth century

From the twentieth century onward Vietnamese people have also worn clothing that is popular internationally. The Áo dài was briefly banned after the fall of Saigon but made a resurgence.[20] Now it is worn in white by high school girls in Vietnam. It is also worn by receptionists and secretaries. Styles differ in northern and southern Vietnam.[21] The current formal national dress is the áo dài for women, suits or áo the for men.

Notes

- Objects for worship, at the National Museum Vietnamese History

- The dress was taken as a trophy by Garnier in the capture of Hanoi in 1873

- Typically light blue but can be found in brown and is similar to the ones worn by Vietnamese Buddhist monastics in regards to the trademark collar similar to the áo dài but without the sleeves with hidden pockets. While there are matching pants they are not a required part of the outfit for laity. A similar version can be found in Cao Đài temples.

References

- A. Terry Rambo (2005). Searching for Vietnam: Selected Writings on Vietnamese Culture and Society. Kyoto University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-920901-05-9.

- T., Van (4 July 2013). "Ancient costumes of Vietnam". VietNamNet Global.

- Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0231138635.

- Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Issue 15. Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 1996. p. 94.

- Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. Congress (1996). Indo-Pacific Prehistory: The Chiang Mai Papers, Volume 2. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. Volume 2 of Indo-Pacific Prehistory: Proceedings of the 15th Congress of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 5–12 January 1994. The Chiang Mai Papers. Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Australian National University. p. 94.

- Trần, Quang Đức (2013). Ngàn năm áo mũ. Vietnam: Công Ty Văn Hóa và Truyền Thông Nhã Nam. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-1629883700.

- Wang, Qi (1609). Sancai Tuhui. China.

- 石渠寶笈秘殿珠林續編 (PDF) (in Chinese).

- The Vietnam Review: VR., Volume 3. Vietnam Review. 1997. p. 35.

- Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-1316531310.

- Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K., eds. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Introduction to Asian Civilizations (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0231511100.

- Organization, Vietnam Centre (2020). Weaving a Realm (Dệt Nên Triều Đại). Vietnam: Dân Trí Publisher. ISBN 978-604-88-9574-7.

- Tran, My-Van (2005). A Vietnamese Royal Exile in Japan: Prince Cuong De (1882–1951). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415297165.

- Howard, Michael C. (2016). Textiles and Clothing of Việt Nam: A History. McFarland. p. 72. ISBN 9781476624402.

- Woodside, Alexander (1988). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 134. ISBN 9780674937215.

- Chanda, Nayan (1986). Brother Enemy: The War After the War (illustrated ed.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 53, 111.

- Chandler, David (2018). A History of Cambodia (4 ed.). Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 978-0429964060.

- Choi, Byung Wook (2018). Southern Vietnam under the Reign of Minh Mang (1820–1841): Central Policies and Local Response. Book collections on Project MUSE (illustrated ed.). Cornell University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1501719523.

- Harms, Erik (2011). Saigon's Edge: On the Margins of Ho Chi Minh City. University of Minnesota Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780816656059.

She then left the room to change out of her áo Ba Ba into her everyday home clothes, which did not look like peasant clothes at all. In Hóc Môn, traders who sell goods in the city don “peasant clothing” for their trips to the city and change back

- Vo, Nghia M. (2011). Saigon: A History. McFarland. p. 202. ISBN 9780786464661.

The new government banned the wearing of the traditional áo dài. Their income from sewing áo dài suddenly plummeted, forcing them to sell everything to survive: refrigerator, radio, food and clothing. Only after the ban was lifted ten years later

- Taylor, Philip (2007). Modernity and Re-enchantment: Religion in Post-revolutionary Vietnam. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 157. ISBN 9789812304407.

The contemporary versions of Áo dài are of considerable sociological interest as they represent regional variations, as well as age and gender arrangements (men rarely wear them nowadays and usually dress in Western-style suits

- Nguyễn Khắc Thuần (2005), Danh tướng Việt Nam, Nhà Xuất bản Giáo dục.

Sources

- Leshkowich, Ann Marie. "History of Ao Dai".

- Ay-leen (20 October 2010). "The Ao Dai and I: A Personal Essay on Cultural Identity and Steampunk".