Tycho Brahe days

In the folklore of Scandinavia, Tycho Brahe days (Danish: Tycho Brahes-dage; Norwegian: Tycho Brahedager; Swedish: Tycho Brahe-dagar) are days judged to be especially unlucky, especially for magical work, and important business transactions (and personal events). Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) was a Danish astronomer, astrologer,[1] and alchemist and as such achieved some acclaim in popular folklore as a sage and magician.

Origins

The idea that certain calendar dates are lucky or unlucky is of ancient origin, going back as far as the Mesopotamian civilizations. Tables that identify lucky and unlucky days are sometimes known by the German label of Tagwählerei. The Coligny calendar also identifies certain calendar dates as lucky or unlucky, and the Roman fasti marks many days and parts of others as dies nefasti, unsuited for the conduct of public business.[2] Contemporary North America preserves a tradition that Friday the 13th is an unlucky day. It has been called a "pervasive form of divination" that "is found in all societies which regulate their days and nights in calendric systems."[3]

The received idea concerning the origin of Tycho Brahe days was that "Tycho Brahe, the celebrated Danish astronomer of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, was very superstitious, considering certain days in the year pregnant with misfortune, wherefore in Denmark, up to this very day, the laboring class call such days on which they happen to meet with some unfortunate accident, Tycho Brahe's days."[4] In his travelogue A Poet's Bazaar, Hans Christian Andersen alludes to the fact that Tycho Brahe died in exile in Prague, observing that "Denmark owns not even his dust; but the Danes mention his name in their bad times, as if a denunciation proceeded out of it: 'These are Tycho Brahe's days!' say they."[5]

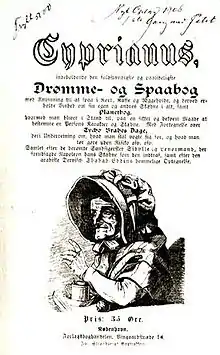

However, no mention of the Tycho Brahe days is actually found in the work of Tycho Brahe.[6] They nevertheless are often referenced in almanacs and recur in Scandinavian folklore. In the Cyprianus tradition, Tycho Brahe days are considered unlucky for magical work; several of the spells in the Black Books of Elverum note that they should not be carried out on a Tycho Brahe day.[7][8]

Days

- Based on the Julian calendar

- January 1, 2, 4, 6, 11, 12, 29

- February 11, 17, 18

- March 1, 4, 14, 15

- April 9, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22, 29

- May 10, 17, 18

- June 6

- July 17, 21

- August 20, 21

- September 16, 18

- October 6

- November 6, 18

- December 6, 11, 18[9][10]

These days were supposed to be unlucky to perform tasks such as getting married, starting a journey, or to fall ill on.[9] Some versions claim that Tycho Brahe also identified several days as particularly lucky:

- January 26

- February 9 and 10

- June 15[11]

Some lists omit certain days, or add others; there is no standard list. Denmark was on the Julian calendar until 1700, when it switched to the Gregorian calendar.[12]

Egyptian days

Medieval calendars often contained lists of dies Ægyptiaci, "Egyptian days", that also were held to be unlucky. The Egyptian days were:

- January 1, 25

- February 4, 26

- March 1, 28

- April 10, 20

- May 3, 25

- June 10, 16

- July 13, 22

- August 1,30

- September 3, 21

- October 3, 22

- November 5, 28

- December 7, 22

These too were days considered unlucky to begin any enterprise. Physicians were especially discouraged from performing bloodletting on the Egyptian days.[13][14]

See also

References

- "Tycho Brahe och Astrology". The Tycho Brahe Museum. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- Smith, William (1875). "A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities". John Murray. pp. Dies. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- Koch, Ulla Suzanne (2010). "Concepts and Perception of Time in Mesopotamian Divination". academia.edu. p. 7. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- Sinding, Paul O. (1865). The Ancient Scandinavians, their maritime expeditions, their discoveries, and their religion. Internet Archive digitized edition: Hunter Rose & Co. p. 19.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Andersen, Hans C. (1831). "The Poet's Bazaar: a picturesque tour in Germany, Italy, Greece, and the Orient". Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- Thoren, Victor (1991). The Lord of Uraniborg: A Biography of Tycho Brahe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 215. ISBN 0521351588.

- Rustad, Mary: The Black Books of Elverum (Galde Press, 1999; ISBN 1-880090-75-9), e.g. p. 49, 116-117

- Stokker, Kathleen: Remedies and rituals: folk medicine in Norway and the New Land (Minnesota Historical Society, 2007; ISBN 0-87351-576-5), p. 79

- Marryat, Horace (1860). A residence in Jutland, the Danish Isles, and Copenhagen. Google scan: J. Murray. pp. 309.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Tykobrahedag - Institutet för språk och folkminnen". www.sprakochfolkminnen.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 2016-02-14. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- "Tycho Brahe-days". www.learning4sharing.nu (in Swedish). Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- Nørby, Toke. "The Perpetual Calendar: A helpful Tool to Postal Historians". norbyhus.dk. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- Quinion, Michael (Mar 3, 2007). "World Wide Words: Egyptian Days". Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- Schmitz, Wilh. “Ein Wolfenbütteler Verzeichnitz Der 'Dies Aegyptiaci'.” Rheinisches Museum Für Philologie, vol. 22, 1867, pp. 303–303. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23078686.