Turkey (bird)

The turkey is a large bird in the genus Meleagris, which is native to the Americas. The genus has two extant species: the wild turkey of eastern and central North America and the ocellated turkey of the Yucatán Peninsula. Males of both turkey species have a distinctive fleshy wattle or protuberance that hangs from the top of the beak (called a snood). They are among the largest birds in their ranges. As with many Galliformes, the male is larger and much more colorful than the female.

| Turkey | |

|---|---|

| |

| A wild turkey | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Subfamily: | Meleagridinae |

| Genus: | Meleagris Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Species | |

The earliest turkeys evolved in North America over 20 million years ago and they share a recent common ancestor with grouse, pheasants, and other fowl.

Taxonomy

Turkeys are classed in the family Phasianidae (pheasants, partridges, francolins, junglefowl, grouse, and relatives thereof) in the taxonomic order Galliformes.[1] The genus Meleagris is the only extant genus in the subfamily Meleagridinae, formerly known as the family Meleagrididae, but now subsumed within the family Phasianidae.

Extant species

| Image | Scientific name | Common name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meleagris gallopavo | wild turkey or domestic turkey | the forests of North America, from Mexico (where they were first domesticated by the Mayans)[2] throughout the midwestern and eastern United States and into southeastern Canada |

| Meleagris ocellata | ocellated turkey | the forests of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico[3] |

Fossil species

| Scientific name | Common name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Meleagris californica | Californian turkey | southern California |

History and naming

Turkeys were domesticated in ancient Mexico for food and for their cultural and symbolic significance.[4] The Aztecs, for example, had a name for the turkey, wueh-xōlō-tl (guajolote in Spanish), a word still used in modern Mexico in addition to the general term pavo. Spanish chroniclers, including Bernal Díaz del Castillo and Father Bernardino de Sahagún, describe the multitude of food (both raw fruits and vegetables as well as prepared dishes) that were offered in the vast markets (tianguis) of Tenochtitlán, noting there were tamales made of turkeys, iguanas, chocolate, vegetables, fruits and more. The ancient people of Mexico had not only domesticated the turkey, but had apparently developed sophisticated recipes including these ingredients—many used to this day—over hundreds of years.

There are two theories for the derivation of the name turkey, both of which may be correct, according to Columbia University professor of Romance languages Mario Pei.[5] One theory is that when Europeans first encountered turkeys in America, they incorrectly identified the birds as a type of guineafowl, which were already being imported into Europe by Turkey merchants via Constantinople and were therefore nicknamed Turkey coqs (Middle Eastern merchants were called Turkey merchants as much of that area was part of the Ottoman Empire at that time). The name of the North American bird thus became turkey fowl or Indian turkeys, which was then shortened to just turkeys.[5][6][7]

A second theory arises from turkeys coming to England not directly from the Americas, but via merchant ships from the Middle East, where they were domesticated successfully. Again the importers lent the name to the bird; hence Turkey-cocks and Turkey-hens, and soon thereafter, turkeys.[5][8]

In 1550, the English navigator William Strickland, who had introduced the turkey into England, was granted a coat of arms including a "turkey-cock in his pride proper".[9] William Shakespeare used the term in Twelfth Night,[10] believed to be written in 1601 or 1602. The lack of context around his usage suggests that the term was already widespread.

Other languages have other names for turkeys. Many of these names incorporate an assumed Indian origin, such as dinde ('from India') in French, индюшка (indyushka, 'bird of India') in Russian, indyk in Polish and Ukrainian, and hindi ('India') in Turkish. These are thought to arise from the supposed belief of Christopher Columbus that he had reached India rather than the Americas on his voyage.[5] In Portuguese a turkey is a peru; the name is thought to derive from the country Peru.[11]

Several other birds that are sometimes called turkeys are not particularly closely related: the brushturkeys are megapodes, and the bird sometimes known as the "Australian turkey" is the Australian bustard (Ardeotis australis). The anhinga (Anhinga anhinga) is sometimes called the water turkey, from the shape of its tail when the feathers are fully spread for drying.

An infant turkey is called a chick or poult.

Human conflicts with wild turkeys

Turkeys have been known to be aggressive toward humans and pets in residential areas.[12] Wild turkeys have a social structure and pecking order and habituated turkeys may respond to humans and animals as they do to another turkey. Habituated turkeys may attempt to dominate or attack people that the birds view as subordinates.[13]

The town of Brookline, Massachusetts, recommends that citizens be aggressive toward the turkeys, take a step toward them and not back down. Brookline officials have also recommended "making noise (clanging pots or other objects together); popping open an umbrella; shouting and waving your arms; squirting them with a hose; allowing your leashed dog to bark at them; and forcefully fending them off with a broom."[14]

Fossil record

A number of turkeys have been described from fossils. The Meleagridinae are known from the Early Miocene (c. 23 mya) onwards, with the extinct genera Rhegminornis (Early Miocene of Bell, U.S.) and Proagriocharis (Kimball Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of Lime Creek, U.S.). The former is probably a basal turkey, the other a more contemporary bird not very similar to known turkeys; both were much smaller birds. A turkey fossil not assignable to genus but similar to Meleagris is known from the Late Miocene of Westmoreland County, Virginia.[3] In the modern genus Meleagris, a considerable number of species have been described, as turkey fossils are robust and fairly often found, and turkeys show great variation among individuals. Many of these supposed fossilized species are now considered junior synonyms. One, the well-documented California turkey Meleagris californica,[15] became extinct recently enough to have been hunted by early human settlers.[16] It has been suggested that its demise was due to the combined pressures of human hunting and climate change at the end of the last glacial period.[17]

The Oligocene fossil Meleagris antiquus was first described by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1871. It has since been reassigned to the genus Paracrax, first interpreted as a cracid, then soon after as a bathornithid Cariamiformes.

Fossil species

- Meleagris sp. (Early Pliocene of Bone Valley, U.S.)

- Meleagris sp. (Late Pliocene of Macasphalt Shell Pit, U.S.)

- Meleagris californica (Late Pleistocene of southwestern U.S.) – formerly Parapavo/Pavo

- Meleagris crassipes (Late Pleistocene of southwestern North America)

Turkeys have been considered by many authorities to be their own family—the Meleagrididae—but a recent genomic analysis of a retrotransposon marker groups turkeys in the family Phasianidae.[18] In 2010, a team of scientists published a draft sequence of the domestic turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) genome.[19]

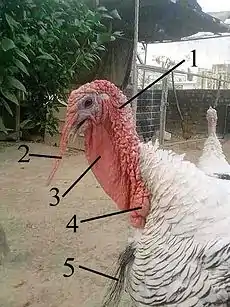

Anatomy

In anatomical terms, the snood is an erectile, fleshy protuberance on the forehead of turkeys. Most of the time when the turkey is in a relaxed state, the snood is pale and 2–3 cm long. However, when the male begins strutting (the courtship display), the snood engorges with blood, becomes redder and elongates several centimetres, hanging well below the beak (see image).[20][21]

Snoods are just one of the caruncles (small, fleshy excrescences) that can be found on turkeys.

While fighting, commercial turkeys often peck and pull at the snood, causing damage and bleeding. This often leads to further injurious pecking by other turkeys and sometimes results in cannibalism. To prevent this, some farmers cut off the snood when the chick is young, a process known as de-snooding.

The snood can be between 3 to 15 centimetres (1 to 6 in) in length depending on the turkey's sex, health, and mood.[22]

Function

The snood functions in both intersexual and intrasexual selection. Captive female wild turkeys prefer to mate with long-snooded males, and during dyadic interactions, male turkeys defer to males with relatively longer snoods. These results were demonstrated using both live males and controlled artificial models of males. Data on the parasite burdens of free-living wild turkeys revealed a negative correlation between snood length and infection with intestinal coccidia, deleterious protozoan parasites. This indicates that in the wild, the long-snooded males preferred by females and avoided by males seemed to be resistant to coccidial infection.[23]

Use by humans

The species Meleagris gallopavo is eaten by humans. They were first domesticated by the indigenous people of Mexico from at least 800 BC onwards. These domesticates were then either introduced into what is now the US Southwest or independently domesticated a second time by the indigenous people of that region by 200 BC, at first being used for their feathers, which were used in ceremonies and to make robes and blankets.[24] Turkeys were first eaten by Native Americans by about AD 1100.[24] Compared to wild turkeys, domestic turkeys are selectively bred to grow larger in size for their meat.[25][26] Americans often eat turkey on special occasions such as at Thanksgiving or Christmas.[27][28]

The Norfolk turkeys

In her memoirs, Lady Dorothy Nevill (1826–1913)[29] recalls that her great-grandfather Horatio Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (1723–1809), imported a quantity of American turkeys[29] which were kept in the woods around Wolterton Hall and in all probability were the embryo flock for the popular Norfolk turkey breeds of today.

Gallery

A male wild turkey strutting

A male wild turkey strutting Chan Chich Lodge area, Belize: the ocellated turkey is named for the eye-shaped spots (ocelli) on its tail feathers

Chan Chich Lodge area, Belize: the ocellated turkey is named for the eye-shaped spots (ocelli) on its tail feathers

References

- Crowe, Timothy M.; Bloomer, Paulette; Randi, Ettore; Lucchini, Vittorio; Kimball, Rebecca T.; Braun, Edward L. & Groth, Jeffrey G. (2006a): "Supra-generic cladistics of landfowl (Order Galliformes)". Acta Zoologica Sinica 52(Supplement): 358–361. PDF fulltext

- "Earliest use of Mexican turkeys by ancient Maya". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- Farner, Donald Stanley & King, James R. (1971). Avian biology. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-249408-6.

- Nield, David. "Study Shows That Humans Domesticated Turkeys For Worshipping, Not Eating". sciencealert.com.

- Krulwich, Robert (27 November 2008). "Why A Turkey Is Called A Turkey". NPR. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- Webster's II New College Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2005, ISBN 978-0-618-39601-6, p. 1217

- Smith, Andrew F. (2006) The Turkey: An American Story. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03163-2. p. 17

- "The flight of the turkey". The Economist. 20 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Boehrer, Bruce Thomas (2011). Animal characters: nonhuman beings in early modern literature. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 141. ISBN 0812201361.

- Twelfth Night: Act 2, Scene 5 No Fear Shakespeare

- Dicionário Priberam da Lingua Portuguesa, "peru".

- Annear, Steve (24 April 2017). "MassWildlife warns of turkey encounters". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- "Preventing Conflicts with Wild Turkeys". Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- Sweeney, Emily (25 August 2017). "Don't let aggressive turkeys bully you, Brookline advises residents". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- Formerly Parapavo californica and initially described as Pavo californica or "California peacock"

- Broughton, Jack (1999). Resource depression and intensification during the late Holocene, San Francisco Bay: evidence from the Emeryville Shellmound vertebrate fauna. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-09828-2.; lay summary

- Bochenski, Z. M., and K. E. Campbell, Jr. (2006). The extinct California Turkey, Meleagris californica, from Rancho La Brea: Comparative osteology and systematics. Contributions in Science, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Number 509.

- Jan, K.; Andreas, M.; Gennady, C.; Andrej, K.; Gerald, M.; Jürgen, B.; Jürgen, S. (2007). "Waves of genomic hitchhikers shed light on the evolution of gamebirds (Aves: Galliformes)". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 190. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-190. PMC 2169234. PMID 17925025. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- Dalloul, R. A.; Long, J. A.; Zimin, A. V.; Aslam, L.; Beal, K.; Blomberg Le, L.; Bouffard, P.; Burt, D. W.; Crasta, O.; Crooijmans, R. P.; Cooper, K.; Coulombe, R. A.; De, S.; Delany, M. E.; Dodgson, J. B.; Dong, J. J.; Evans, C.; Frederickson, K. M.; Flicek, P.; Florea, L.; Folkerts, O.; Groenen, M. A.; Harkins, T. T.; Herrero, J.; Hoffmann, S.; Megens, H. J.; Jiang, A.; De Jong, P.; Kaiser, P.; Kim, H. (2010). Roberts, Richard J (ed.). "Multi-Platform Next-Generation Sequencing of the Domestic Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo): Genome Assembly and Analysis". PLOS Biology. 8 (9): e1000475. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000475. PMC 2935454. PMID 20838655.

- ENature.com (2010). "Snoods and wattles? A turkey's story". Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- Graves, R.A. (2005). "Know your turkey parts". Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- Melissa Mayntz (28 August 2019). "The Turkey's Snood". Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Buchholz, R. "Mate choice research". Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- "Native Americans First Tamed Turkeys 2,000 Years Ago". Seeker (Discovery News). Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- "Amazing Facts About Turkey". OneKind. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "My Life as a Turkey – Domesticated versus Wild Graphic". PBS. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- "Why do we eat turkey for Thanksgiving and Christmas?". Slate. 25 November 2009. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "Why Do We Eat Turkey on Thanksgiving?". Wonderopolis. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Nevill, Lady Dorothy (1894). Mannington and the Walpoles, Earls of Orford. With ten illustrations of Mannington Hall, Norfolk (PDF). London: Fine Art Society. p. 22. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

External links

| Look up turkey in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Meleagris at Curlie

- View the melGal1 genome assembly in the UCSC Genome Browser.