Tuberculosis radiology

Radiology (X-rays) is used in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Abnormalities on chest radiographs may be suggestive of, but are never diagnostic of TB, but can be used to rule out pulmonary TB.

Chest X-ray

A posterior-anterior (PA) chest X-ray is the standard view used; other views (lateral or lordotic) or CT scans may be necessary.

In active pulmonary TB, infiltrates or consolidations and/or cavities are often seen in the upper lungs with or without mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy.[1] However, lesions may appear anywhere in the lungs. In HIV and other immunosuppressed persons, any abnormality may indicate TB or the chest X-ray may even appear entirely normal.[1]

Old healed tuberculosis usually presents as pulmonary nodules in the hilar area or upper lobes, with or without fibrotic scars and volume loss.[1] Bronchiectasis and pleural scarring may be present.

Nodules and fibrotic scars may contain slowly multiplying tubercle bacilli with the potential for future progression to active tuberculosis.[1] Persons with these findings, if they have a positive tuberculin skin test reaction, should be considered high-priority candidates for treatment of latent infection regardless of age. Conversely, calcified nodular lesions (calcified granuloma) pose a very low risk for future progression to active tuberculosis.

Abnormalities on chest radiographs may be suggestive of, but are never diagnostic of, TB.[1] However, chest radiographs may be used to rule out the possibility of pulmonary TB in a person who has a positive reaction to the tuberculin skin test and no symptoms of disease.

CDC guidelines for evaluating CXR

The chest X-ray and classification worksheet by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States is designed to group findings into categories based on their likelihood of being related to TB or non-TB conditions needing medical follow-up.[2]

Normal findings

These are films that are completely normal, with no identifiable cardiothoracic or musculoskeletal abnormality.

Chest X-ray findings that can suggest active TB

This category comprises all findings typically associated with active pulmonary TB.[2] In the US, refugees or immigration applicants with any of the following findings must submit sputum specimens for examination.[2]

1. Infiltrate or consolidation - Opacification of airspaces within the lung parenchyma. Consolidation or infiltrate can be dense or patchy and might have irregular, ill-defined, or hazy borders.

Dense homogenous opacity in right, middle and lower lobe of primary pulmonary TB.

Dense homogenous opacity in right, middle and lower lobe of primary pulmonary TB. Chest x-ray showing patchy opacification on the upper right and mid-zone lung with fibrotic shadows, as well as bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy.

Chest x-ray showing patchy opacification on the upper right and mid-zone lung with fibrotic shadows, as well as bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Chest x-ray showing coarse reticulonodular densities on the lower right lung of post-primary pulmonary TB.

Chest x-ray showing coarse reticulonodular densities on the lower right lung of post-primary pulmonary TB. Chest x-ray of Ghon's complex of active tuberculosis

Chest x-ray of Ghon's complex of active tuberculosis

2. Any cavitary lesion - Lucency (darkened area) within the lung parenchyma, with or without irregular margins that might be surrounded by an area of airspace consolidation or infiltrates, or by nodular or fibrotic (reticular) densities, or both. The walls surrounding the lucent area can be thick or thin. Calcification can exist around a cavity.

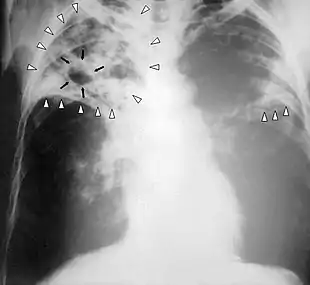

Chest X-ray of a person with advanced tuberculosis: Infection in both lungs is marked by white arrow-heads, and the formation of a cavity is marked by black arrows.

Chest X-ray of a person with advanced tuberculosis: Infection in both lungs is marked by white arrow-heads, and the formation of a cavity is marked by black arrows.

3. Nodule with poorly defined margins - Round density within the lung parenchyma, also called a tuberculoma. Nodules included in this category are those with margins that are indistinct or poorly defined (tree-in-bud sign[3]). The surrounding haziness can be either subtle or readily apparent and suggests coexisting airspace consolidation.

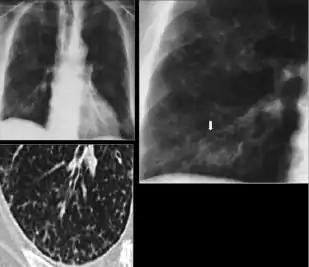

Chest x-ray showing nodule with margins that are indistinct or poorly defined (tree-in-bud sign) in post-primary pulmonary TB.

Chest x-ray showing nodule with margins that are indistinct or poorly defined (tree-in-bud sign) in post-primary pulmonary TB.

4. Pleural effusion - Presence of a significant amount of fluid within the pleural space. This finding must be distinguished from blunting of the costophrenic angle, which may or may not represent a small amount of fluid within the pleural space (except in children when even minor blunting must be considered a finding that can suggest active TB).

Chest x-ray showing dense opacity pleural effusion in the lower left lung of primary pulmonary TB.

Chest x-ray showing dense opacity pleural effusion in the lower left lung of primary pulmonary TB.

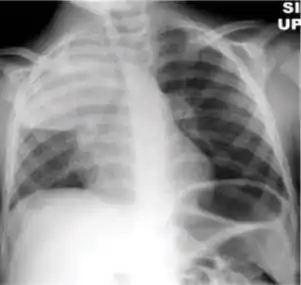

5. Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy (bihilar lymphadenopathy) - Enlargement of lymph nodes in one or both hila or within the mediastinum, with or without associated atelectasis or consolidation.

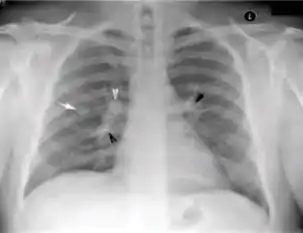

Chest x-ray showing bilateral hilar adenopathy of primary pulmonary TB

Chest x-ray showing bilateral hilar adenopathy of primary pulmonary TB

6. Linear, interstitial disease (in children only) - Prominence of linear, interstitial (septal) markings.

Chest x-ray showing Kerely B line due to interstitial oedema (in children only) of primary pulmonary tuberculosis.

Chest x-ray showing Kerely B line due to interstitial oedema (in children only) of primary pulmonary tuberculosis.

7. Other - Any other finding suggestive of active TB, such as miliary TB. Miliary findings are nodules of millet size (1 to 2 millimeters) distributed throughout the parenchyma.

Chest X-ray findings that can suggest inactive TB

This category includes findings that are suggestive of prior TB, that is inactive. Assessments of the activity of TB cannot be made accurately on the basis of a single radiograph alone. If there is any question of active TB, sputum smears must be obtained. Therefore, any applicant might have findings grouped in this category, but still have active TB as suggested by the presence of signs or symptoms of TB, or sputum smears positive for AFB.[2]

The main chest X-ray findings that can suggest inactive TB are:[2]

1. Discrete fibrotic scar or linear opacity—Discrete linear or reticular densities within the lung. The edges of these densities should be distinct and there should be no suggestion of airspace opacification or haziness between or surrounding these densities. Calcification can be present within the lesion and then the lesion is called a “fibrocalcific” scar.

Chest x-ray showing fibrocalcific scar after secondary tuberculosis as air-space opacification or haziness between or surrounding these densities.

Chest x-ray showing fibrocalcific scar after secondary tuberculosis as air-space opacification or haziness between or surrounding these densities.

2. Discrete nodule(s) without calcification—One or more nodular densities with distinct borders and without any surrounding airspace opacification. Nodules are generally round or have rounded edges. These features allow them to be distinguished from infiltrates or airspace opacities. To be included here, these nodules must be noncalcified. Nodules that are calcified are included in the category “OTHER X-ray findings, No follow-up needed”.

Chest x-ray showing discrete round nodule(s) with round edges without calcification, after secondary tuberculosis.

Chest x-ray showing discrete round nodule(s) with round edges without calcification, after secondary tuberculosis.

3. Discrete fibrotic scar with volume loss or retraction—Discrete linear densities with reduction in the space occupied by the upper lobe. Associated signs include upward deviation of the fissure or hilum on the corresponding side with asymmetry of the volumes of the two thoracic cavities.

Chest x-ray showing distinct fibrotic scar with volume loss or retraction with an upward deviation of the fissure or hilum on the corresponding side with asymmetry of the volumes of the two thoracic cavities.

Chest x-ray showing distinct fibrotic scar with volume loss or retraction with an upward deviation of the fissure or hilum on the corresponding side with asymmetry of the volumes of the two thoracic cavities.

4. Discrete nodule(s) with volume loss or retraction—One or more nodular densities with distinct borders and no surrounding airspace opacification with reduction in the space occupied by the upper lobe. Nodules are generally round or have rounded edges.

Chest x-ray showing nodular densities with distinct borders and no surrounding airspace opacification, with a reduction in the space occupied by the upper lobe.

Chest x-ray showing nodular densities with distinct borders and no surrounding airspace opacification, with a reduction in the space occupied by the upper lobe.

5. Other—Any other finding suggestive of prior TB, such as upper lobe bronchiectasis. Bronchiectasis is bronchial dilation with bronchial wall thickening.

Chest x-ray showing course bronchiectasis of the lungs post-primary pulmonary tuberculosis.

Chest x-ray showing course bronchiectasis of the lungs post-primary pulmonary tuberculosis.

Follow-up needed

This category includes findings that suggest the need for a follow-up evaluation for non-TB conditions.[2]

- Musculoskeletal abnormalities - New bony fractures or radiographically apparent bony abnormalities that need follow-up.

- Cardiac abnormalities - Cardiac enlargement or anomalies, vascular abnormalities, or any other radiographically apparent cardiovascular abnormality of significant nature to require follow-up.

- Pulmonary abnormalities - Pulmonary finding of a non-TB nature, such as a mass, that needs follow-up.

- Other - Any other finding that the panel physician believes needs follow-up, but is not one of the above.

No follow-up needed

This category includes findings that are minor and not suggestive of TB disease. These findings require no follow-up evaluation.[2]

- Pleural thickening - Irregularity or abnormal prominence of the pleural margin, including apical capping (thickening of the pleura in the apical region). Pleural thickening can be calcified.

- Diaphragmatic tenting - A localized accentuation of the normal convexity of the hemidiaphragm as if “pulled upwards by a string.”

- Blunting of costophrenic angle (in adults)—Loss of sharpness of one or both costophrenic angles. Blunting can be related to a small amount of fluid in the pleural space or to pleural thickening and, by itself, is a non-specific finding (except in children, when even minor blunting may suggest active TB). In contrast a large pleural effusion, or the presence of a significant amount of fluid in the pleural space, may be a sign of active TB at any age.

- Solitary calcified nodules or granuloma - Discrete calcified nodule or granuloma, or calcified lymph node. The calcified nodule can be within the lung, hila, or mediastinum. The borders must be sharp, distinct, and well defined. This was considered a Class B3 TB in the past; however, Class B3 has been omitted from the classification scheme because it has not been found to be associated with active TB.

- Minor musculoskeletal findings - Minor findings needing no follow-up.

- Minor cardiac findings - Minor findings needing no follow-up.

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis

Peritoneal tuberculosis may mimic peritoneal carcinomatosis on CT scan.[4]

There is low-quality evidence that abdominal ultrasound has 63% sensitivity and 68% specificity in diagnosing abdominal tuberculosis when tuberculosis is bacteriologically confirmed in HIV-positive individuals. Therefore a negative abdominal ultrasound finding does not rule out the disease due to its low sensitivity.[5]

References

- Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; & Mitchell, Richard N. (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 516-522 ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1

- "Instructions to Panel Physicians for Completing New U.S. Department of State MEDICAL EXAMINATION FOR IMMIGRANT OR REFUGEE APPLICANT (DS-2053) and Associated WORKSHEETS (DS-3024, DS-3025, and DS-3026)" (PDF). visa-21.com. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Rossi, S. E.; Franquet, T.; Volpacchio, M.; Gimenez, A.; Aguilar, G. (1 May 2005). "Tree-in-Bud Pattern at Thin-Section CT of the Lungs: Radiologic-Pathologic Overview". Radiographics. 25 (3): 789–801. doi:10.1148/rg.253045115. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- Akce, Mehmet; Bonner, Sarah; Liu, Eugene; Daniel, Rebecca (2014). "Peritoneal Tuberculosis Mimicking Peritoneal Carcinomatosis". Case Reports in Medicine. 2014: 1–3. doi:10.1155/2014/436568. ISSN 1687-9627. PMC 3970461. PMID 24715911. CC-BY 3.0

- Van Hoving DJ, Griesel R, Meintjes G, Takwoingi Y, Maartens G, Ochodo EA (30 September 2019). "Abdominal ultrasound for diagnosing abdominal tuberculosis or disseminated tuberculosis with abdominal involvement in HIV-positive individuals". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD012777. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012777.pub2. PMC 6766789. PMID 31565799.

External links

Additional X-ray images

- Chest X-ray Atlas - Select Diseases|Tuberculosis for TB CXR case studies (X-ray pictures showing cavities, infiltrates, scarring, pleural effusion, interstitial nodules of military TB, and TB spine) - from Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine ©

- Teaching File Radiology of Tuberculosis