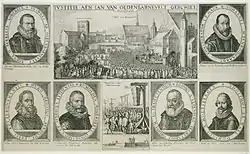

Trial of Oldenbarnevelt, Grotius and Hogerbeets

The Trial of Oldenbarnevelt, Grotius and Hogerbeets was the trial for treason of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Land's Advocate of Holland, Hugo Grotius, pensionary of Dordrecht, Rombout Hogerbeets, pensionary of Leiden, and their co-defendant Gilles van Ledenberg, secretary of the States of Utrecht by an ad hoc court of delegated judges of the States General of the Netherlands that was held between 29 August 1618 and 18 May 1619, and resulted in a death sentence for Oldenbarnevelt, and sentences of life in prison for Grotius and Hogerbeets. The trial was and is controversial for political and legal reasons: political, because it put the crown on the Coup d'etat of stadtholder Maurice, Prince of Orange and his partisans in the States General of the Dutch Republic that ended the previous Oldenbarnevelt regime and put the Orangist party in power for the time being; legal, because the trial deprived the defendants of their civil rights under contemporary law, and the judges changed both the "constitution" of the Republic and its laws in an exercise of ex post facto legislation.

Background

The constitutional "maxims" of the Oldenbarnevelt regime

The Dutch Republic was formed when a number of the polities (duchy, counties, heerlijkheden) constituting the former Habsburg Netherlands concluded the defensive Union of Utrecht in 1579. This treaty preceded the actual "declaration of independence" (the Act of Abjuration of 1581) of the new country, which partially explains why most of the governmental institutions, like the States General, the Council of State, the States ("parliaments") of the several provinces, the stadtholderates, the courts (like the Hof van Holland and the Hoge Raad van Holland en Zeeland), the local administrations, and most of the laws and legal structure were simply continued as if nothing had happened. But soon these old institutions received new roles, which implied a change in their constitutional and legal relationships, and in their political and power relationships. After 1587 (when the last foreign Governor-General, Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, returned to England, leaving a constitutional vacuum), the still young Land's Advocate of the States of Holland and West Friesland, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt took the lead in promoting a number of constitutional reforms in his own province (and through its preponderant role in the Republic also on the confederal level) that changed the "constitution" (in the sense of written and unwritten fundamental legal and political arrangements) of the country in a radical way. It may be useful to describe the new regime in a number of "maxims":[Note 1]

- Sovereignty in the hands of the States[Note 2] of the several provinces of the Republic, and therefore not in the hands of the States General, or of the stadtholders of the several provinces (of which at this time there were two: Maurits in five of the seven provinces, and William Louis, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, in Friesland and Groningen);

- the stadtholders subordinated to the States of their provinces, who appointed them and issued the Instruction that defined their powers and duties;

- under art. XIII of the Union of Utrecht authority of the States of the provinces over the public church (the Dutch Reformed Church) in their provinces and solely competent to regulate matters of religion, like Freedom of Worship, according to the principle of Cuius regio, eius religio, without interference of other States, or the States General, but always respecting the basic right of Freedom of Conscience;

- matters of external defense (and foreign affairs) delegated to the States General with their Captain general (of the Dutch States Army) and Admiral General, but without this delegation implying subordination of the provincial States to the States General, or the (partial) transfer of provincial sovereignty to the States General;

- maintenance of public order (internal defense) a matter for local authorities, regulated by their province's States, and the local and provincial courts, aided by the schutterijen in the cities, with the authority for local authorities to hire waardgelders (auxiliary mercenary troops[Note 3]) in case of need;

- the right to political decision-making reserved for the oligarchy of the Regenten and nobility.[1]

"Truce Quarrels"

Oldenbarnevelt and stadtholder Maurice had been operating hand in glove during the first decades of the Republic's existence, but this changed when Oldenbarnevelt decided to start negotiations with the Habsburg government in Brussels about a cessation of hostilities, after the Eighty Years' War entered a stalemate around 1607. Maurice was opposed to these peace feelers, and so were the city of Amsterdam and the province of Zeeland. This difference of opinion caused a breach between the erstwhile allies, especially after Oldenbarnevelt prevailed and concluded the Twelve Years' Truce in 1609. The conflict about the negotiations was accompanied by much popular political unrest which occasioned a pamphlet war during which Oldenbarnevelt's opponents accused him of secretly colluding with the enemy. These accusations (which Maurice seemed to have believed up to a point) resurfaced during the later trial[2]

After external hostilities ceased, an already raging internal conflict escalated. This led to the so-called Bestandstwisten (Truce Quarrels), as the episode is known in Dutch historiography. Partisans of two professors of theology at Leiden University, Jacobus Arminius and Franciscus Gomarus, who disagreed about the interpretation of the dogma of Predestination, brought the academic polemic to the attention of the Holland authorities by issuing a so-called "Remonstrance" from the Arminian side, followed by a "Counter-Remonstrance" from the Gomarist side in 1610. The authorities indeed had a responsibility for the good order in the Dutch Reformed Church and under the influence of the doctrine of Erastianism took up that responsibility with alacrity. Their main concern, however, was not to take sides in the doctrinal conflict, but to avoid a schism in the Reformed Church. When attempts at reconciliation failed the Oldenbarnevelt regime in Holland embarked on a policy of "forced toleration". This policy (of which Grotius was the main author) was embedded in the placard (statute) "For the Peace of the Church" of January 1614, which was adopted by the States of Holland with a minority, led by Amsterdam (a bastion of the Counter-Remonstrants) opposed. The Counter-Remonstrants demanded a National Synod of the Reformed Church to decide the doctrinal conflict. But Oldenbarnevelt and Grotius opposed this, because they feared this could only lead to a schism, and also because a National Synod might impose on the privilege of Holland to regulate religious matters without interference from other provinces.[3]

The "Tolerance placard" meanwhile led to popular unrest, because it was enforced only in towns with Remonstrant magistrates, and therefore only used against Counter-Remonstrant preachers who disobeyed the prohibition of preaching about the conflict from the pulpit.[Note 4] The preachers were dismissed from their livings (paid for by the local authorities), but then simply moved to neighboring congregations where they attracted large audiences of church-goers with the same doctrinal convictions. Instead of averting the feared schism the placard therefore seemed to promote it, also because opposing preachers refused to recognize each other's qualification to administer the Lord's Supper. Soon the followers of either side demanded their own churches, whereas the authorities wanted them to use the same ones. This eventually led to Counter-Remonstrants using mob violence to occupy their own churches, like the Cloister Church in the capital of Holland and the Republic, The Hague in the Summer of 1617. As far as Oldenbarnevelt was concerned this defiance of the authority of the civil authorities could not be tolerated, and he promoted the adoption of the so-called Sharp Resolution of 4 August 1617 by the States of Holland.[4]

This resolution authorized civil authorities in Holland cities to recruit waardgelders to maintain public order. This was objectionable to Maurice as Captain-General of the States Army, because the new troops would only swear an oath of allegiance to their city magistrates, and not to the States General and himself, as was usual for similar mercenary troops. This opened the possibility that these waardgelders would come into armed conflict with his own federal troops. To make matters worse in his view, the Resolution also ordered federal troops that were paid for by the Holland repartitie (contribution to the federal budget) to follow the orders of their Holland paymasters in case of conflict between his orders and theirs. Maurice, supported by the opposition to Oldenbarnevelt in the States of Holland, led by Amsterdam, protested vehemently against the Resolution, and when the recruitment of waardgelders nevertheless was implemented in several Remonstrant cities, and also in Utrecht (where the States had taken a similarly worded Resolution), he started to mobilize the opposition against Oldenbarnevelt.[5]

Though many expected an immediate military coup, Maurice moved with deliberation, and embarked on a policy of intimidation of the magistracies of cities supporting Oldenbarnevelt in Holland and in other provinces, causing them to change their vote in the States and in the States General. He also started to support the policy of the Counter-Remonstrants to convoke a National Synod by the States General. This more and more isolated Oldenbarnevelt and his allies like Grotius and the pensionaries of Leiden (Hogerbeets) and Haarlem (Johan de Haen) in the States of Holland and in the States General. Maurice's maneuvers were reciprocated by the Oldenbarneveltians where they could. An example was the episode in June, 1618, of the deputation of the States of Utrecht that had been sent to negotiate an accommodation with Maurice (in his capacity of Captain-General) in which the Utrecht States would dismiss their waardgelders in exchange for the replacement of French federal city-garrison troops with more amenable Dutch nationals. When the Utrecht deputation arrived in The Hague they were "waylaid" by Grotius and Hogerbeets at the home of the Remonstrant preacher Johannes Wtenbogaert in a successful attempt to convince them to keep their message for Maurice to themselves, and return to Utrecht. This was later construed as a treasonous conspiracy.[6][7]

In July 1618 Maurice decided that the time was ripe to act against the waardgelders in Utrecht. On the ground that under the Union of Utrecht all matters of defense pertained to the States General that body voted a Resolution (opposed by Holland and Utrecht) to disband the waardgelders in Utrecht city. To that end a delegation under leadership of Maurice was sent to the city to enforce the Resolution, of course accompanied by a strong force of federal troops. Before that delegation had arrived, however, Oldenbarnevelt had a Resolution taken by a minority of members of the States of Holland (and therefore arguably illegal) to send a counter-delegation to the Utrecht States to convince them to oppose the disbandment, with armed force if need be. This delegation was led by Grotius and Hogerbeets and it arrived before the delegation of the States General. Grotius not only convinced the Utrecht States to try and oppose Maurice, but he also drafted a memorandum for them wherein they argued their stance with an appeal to the doctrine of absolute sovereignty of provincial States in matters of religion and the maintenance of public order, and a rejection of Maurice's standpoint that the States General had sovereignty in defense matters.[8] But Maurice was not impressed with this piece of rhetoric and proceeded with the disbandment of the waardgelders, not however, before Grotius had vainly tried to convince the commanders of the federal garrison in Utrecht (who were paid by Holland) to disobey Maurice.[9]

Oldenbarnevelt then realized that he had lost and that further resistance was hopeless. The Holland cities disbanded their waardgelders voluntarily at the end of August 1618. The States of Holland acquiesced in the convocation of the National Synod. But it was too late to save the Oldenbarnevelt regime. The States General took a secret Resolution on 28 August 1618 that authorized Maurice and a commission of non-Holland members of the States general to investigate Oldenbarnevelt and his "co-conspirators" and do what was necessary to ensure the security of the state. Maurice arrested Oldenbarnevelt, Grotius and Hogerbeets the next day at the Binnenhof; Ledenberg was a few days later arrested in Utrecht and extradited to The Hague. This completed the coup d'etat.[10]

Dutch Law of Treason

Like the other political and legal institutions the body of civil and criminal law of the Republic, known in the Anglophone literature as Roman-Dutch law, was a continuation of the quilt of customs, statutes and Roman Law that had existed under the Habsburgs. As to the Law of Treason that originally consisted in the Roman-Law concept of crimen laesae majestatis, derived from Justinian's Digest. This concept had already been used by the Hof van Holland under its Instruction of 1462 of Count Philip I, but it was confirmed by the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina ("Carolina", for short), the criminal code and code of criminal procedure that Count Charles II, in his capacity of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor had had promulgated in 1532 for the entire Holy Roman Empire[Note 5] by the Diet of Regensburg. Before that the application of the concept in actual prosecutions had been very sparse in Holland,[11] but Charles and his son Count Philip III (better known as Philip II of Spain) used it with alacrity in its variant of crimen laesae majestatis divinae in trials for witchcraft and for heresy.[12] During the repression by the Duke of Alba in 1567-68 the "secular" form was used by the Council of Troubles in about 1000 cases in the Netherlands as a whole. In the Digest the crime had been defined as: "any act with malicious intent by which the enemies of the Roman people may be assisted in their designs against the res publica" .[13] This had from the 12th century on been applied by learned jurists as a crime against the "majesty" of the sovereign lord, under the maxim rex in rego suo principes est (the king in his realm is the highest power).[13]

However, this application could not as easily be effected in the Dutch Republic after the States of Holland had drawn the mantle of sovereignty upon themselves in 1587, when they made the "Deduction" of François Vranck the law of the land. It was clear that the sovereign no longer was a single person (as the Count of Holland), but an assembly of legal entities (18 voting cities and the ridderschap or College of Nobles). In the conceptualisation of Vranck the concept of maiestas was "split off" from that of sovereignty.[14]

This was reflected in the first piece of legislation in the matter of treason by the States of Holland after its assumption of sovereignty, the placard of 27 November 1587. Here treason was defined as "seditious writings, conspiracies, surreptitious assaults, and the scattering of pasquilts ...that stir up sedition and the diminution of the authority of their government, magistrates and the courts of the cities". In other words "diminution of authority", not of "majesty" was the core of the offense, because the authorities are the legitimate guardians of public order.[15]

After the Betrayal of Geertruidenberg the States General also passed a piece of treason legislation that retro-actively branded the mutineers "traitors" and outlawed them as "disturbers of the peace". This term returned in the Act of the States General of 12 April 1588 in which it was termed an act of "treason" if troops of the States Army remained loyal to Leicester, who was dismissed as Governor-General in the same Act. Such disobedience to the States General was, however, not defined as a violation of majestas, but of the exercise of the highest public authority. In sum, in these treason statutes no reference was made to the old laesio majestatis, but to the new concept of "perturbation of the public peace" as the essence of "treason."[16][Note 6]

In the Dutch vernacular of the period (and later) the terms landverraad (betrayal of country) in the sense of "aiding the enemy in making war on the country", and hoogverraad (high treason) in the sense of "attempting to violate the security of the state" were used (even by Oldenbarnevelt in his peroration on the scaffold at his execution). However, these were not legal terms; both crimes were comprehended under the general legal concept of treason as described above.[17]

Treason, however defined, was a halsmisdrijf (capital crime), for which the Carolina prescribed a special criminal procedure, known as the processus extraordinaris. Other than the processus ordinaris (used in civil cases and minor criminal cases) this was a procedure of the inquisitorial type, completely different from the adversarial system used in Anglo-Saxon jurisdictions. The extraordinaris trial consisted of first an informative stage (informatie precedente or inquisitio generalis) in which the court investigated the facts and considered whether a crime had been committed. Only after this stage had been concluded could the suspect be arrested and the second stage of the inquisitio specialis begin. This did not start with an indictment and a plea by the defendant, but the court focused the investigation it continued from the informative stage on the defendant. Usually the defendant was interrogated and witnesses were heard. A conviction had to be based on either the evidence of two or more witnesses, or a confession by the defendant. Because in view of the possible consequences most defendants were unwilling to confess, the court could order the application of torture to force a confession, but only if sufficient circumstantial evidence ("half proof") was available. Such a forced confession was, however, in itself insufficient to warrant a conviction. The confession had to be confirmed by the defendant in open court in the absence of undue pressure (the formula in verdicts was buiten pijne ende banden van ijsere, or "without torture and fetters of iron"). Without such a valid confession the death penalty could not be pronounced.[18]

In the trial of Oldenbarnevelt c.s. the court apparently ordered an intendit. This term has defeated many historians. It was not an "indictment" (as Van den Bergh thinks), nor something comparable to the Conclusion or Opinion given by an Advocate general before the Court of Justice of the European Union (as Uitterhoeve states[19]), nor is it a requisitoir (summing up by the prosecutor) as in modern Dutch criminal cases. The legal concept intendit was found in two contexts in Dutch civil procedural law, firstly in default cases, where the plaintiff was allowed to enter an intendit after the fourth failure of the defendant to appear in court; secondly after the interlocutory order of the court to grant an appointement bij intendit. In both cases it meant a document that contains an exposition of the case of the plaintiff with his supporting evidence. In the second case the order was granted if the defendant denied the facts as presented by the plaintiff, without offering any evidence to support his denial. Alternatives were appointement in feite contrarie (in which case the defendant offered contrary evidence and parties had to prove who was right) and appointement bij memoriën (if the dispute was not about facts, but about points of law).[20] In criminal cases, however, an intendit seems to have been ordered from the prosecutor, again as an exposition of his case, but to act as a guide for further interrogation of witnesses.[21]

The Trial

The arrests

The secret resolution of the States General of 28 August 1618 apparently had not been kept completely secret, because in the evening of 28 August two justices in the Hof van Holland (one of them Adriaan Teding van Berkhout[22]) came to the house of Oldenbarnevelt at Kneuterdijk[Note 7] to warn him of his impending arrest, but he did not heed the warning. The next day he rode the short distance to the Binnenhof, where the government center was located, in his carriage (because he had difficulty walking, due to arthritis), accompanied by his personal servant, Jan Francken. When he arrived at his office in the building of the States of Holland a servant of the stadtholder asked him to come to Maurice's personal apartments for "a chat". When he arrived there, he was arrested by the captain of Maurice's personal bodyguard, Pieter van der Meulen. The same subterfuge was used to snare Grotius and Hogerbeets. All three were initially detained in the apartments of the stadtholder under guard. But after a few days they were transferred to a kind of makeshift jail above the Rolzaal (Audience Chamber) of the Hof van Holland behind what is now called the Ridderzaal. These were the rooms that had previously held the Spanish admirante Francisco de Mendoza as a prisoner of war after his capture at the Battle of Nieuwpoort in 1600. Oldenbarnevelt got Mendoza's former room; Grotius the room next to that; and Hogerbeets the room across the corridor, while Ledenberg got a room further down the hall. Later a guardroom was constructed to house the armed guard.[23]

The arrests had been unprecedented, if not downright illegal. It had never happened before that servants of the sovereign States of Holland had been arrested by another political body of the Republic on its own territory without its consent and without a proper warrant under Holland law. In addition, Oldenbarnevelt had in June received a safeguard[Note 8] from the States of Holland to protect him from arbitrary arrest.[24] The arrest had been effected by the federal military, with questionable jurisdiction over civilians, on the orders of Maurice, not in his capacity of Holland stadtholder, but of that of Captain-General of the States Army. There had been no regular civil authorities like the baljuw of The Hague involved, and the prisoners were not detained in the Gevangenpoort, the regular city jail. The prisoners were guarded by federal troops from Maurice's personal guard. In other words, all of this was highly irregular. The prisoners and their families and friends immediately took steps to effect their release. Oldenbarnevelt's sons-in-law, Brederode, president of the Hoge Raad van Holland en Zeeland, and Cornelis van der Mijle (a member of the Holland ridderschap) pleaded with Maurice, but to no avail.[25] Subsequent attempts to institute proceedings before the Hof van Holland did not have the wished-for result.[Note 9] The States of Holland debated whether to enter a formal protest with the States General, but because of parliamentary maneuvers by the Amsterdam delegation this came to nothing also.[26]

The whole affair caused civil unrest in The Hague and because of this the States General decided to have an anonymous pamphlet printed in which it was asserted that during the recent mission of the States-General delegation to Utrecht certain "facts had been discovered, that had caused great suspicion" and that indicated the risk "of a bloodbath" and this had made it necessary to arrest the "principal suspects"[27][Note 10] The envoys of England (Dudley Carleton, 1st Viscount Dorchester, [Note 11]) and France (Benjamin Aubery du Maurier), were informed, but Carleton did not protest, and the Frenchman only in a muted fashion. After a while calm returned and most people forgot about the matter, as the following trial was held in camera.[25]

The Court

As the States General was rather new to the notion of their own, special sovereignty, they did not possess their own permanent judiciary, though they did convene crijghsraden (courts-martial) to try military personnel for military offenses.[28] But apparently convening a court-martial was never considered. The judiciary of the Dutch Republic was organised by province in hierarchies of local and regional courts with the provincial high court or Hof at the apex. In the province of Holland the competent court for cases of treason was the Hof van Holland.[29] As three of the prisoners were servants of the States of Holland it would seem that they therefore ought to be tried before this court. As a matter of fact, under the maxim of the Jus de non evocando they even had the right to be tried by that court.[Note 12] But there were practical problems with this. In the first place the partisans of Oldenbarnevelt at this time were still in the majority in the States of Holland, making it unlikely that they would agree with a prosecution and instruct the procureur-generaal (solicitor general) at the court to open one. In addition the justices in both the Hof van Holland and the Hoge Raad were "clients" of Oldenbarnevelt and friends of the other prisoners (Hogerbeets had been a justice in the Hof himself; van Brederode, the son-in-law of Oldenbarnevelt was president of the Hoge Raad). Finally, the Hof would insist on following existing law and precedent, and here the case for the prosecution was extremely weak, as will become clear in the sequel.

Maurice and his allies in the States General therefore felt that they had to come up with an alternative. Already in the secret resolution of 28 August mention is made of the commissioners who had accompanied Maurice to Utrecht to disarm the waardgelders there, and who had done "good work". So they were now charged with investigating the matter as commissioners of the States General.[30] These commissioners were Nicolaes de Voogd, delegate of Gelderland, Adriaan Mandemaker, delegate of Zeeland, Adriaan Ploos, delegate of Utrecht, Abel Coenders, delegate of Groningen (who was later replaced by another delegate of Groningen), and Rink Aitsma, delegate of Friesland. They were assisted by two advocaten fiscaal (prosecutors), Pieter van Leeuwen, procureur-generaal in the Hof van Utrecht, and Laurens de Silla, an advocate in the Hof van Gelderland. Hendrik Pots, who worked as a solicitor at the Hof van Holland was appointed the griffier (Court clerk). Later Anthonie Duyck was appointed as a third fiscal[31]

But this was an unsatisfactory arrangement. In the Fall of 1618 Maurice continued the political "alteration" in Holland by visiting a number of the "Remonstrant" cities, usually with a strong armed escort, and changing their governments (a practice known as verzetten van de wet) by replacing pro-Oldenbarnevelt burgomasters and vroedschappen with Counter-Remonstrant ones. In this way the States of Holland had an anti-Oldenbarnevelt majority by January, 1619. It then became possible to supplement the original delegated judges with a number of judges from Holland, with the consent of the States of Holland. In total 12 Judges from Holland were appointed and 12 judges from the other six provinces (two for each).[31]

The 24 members of the Court were:[Note 13]

- Nicolaes de Voogd (president), burgomaster of Arnhem, for Gelderland;

- Hendrik van Essen, Councillor of Zutphen, for Gelderland;

- Nicolaas Kromhout, president, Hof van Holland, for Holland;

- Adriaan Junius, justice, Hof van Holland, for Holland;

- Pieter Kouwenburg van Belois, justice, Hof van Holland, for Holland;

- Hendrik Rosa, justice, Hof van Holland, for Holland;

- Adriaan van Zwieten, baljuw of Rijnland, for Holland;

- Hugo Muys van Holy, schout of Dordrecht, for Holland;

- Arent Meinertsz, burgomaster of Haarlem, for Holland;

- Gerard Beukelsz. van Zanten, gecommitteerde raad of Holland, for Holland;

- Jacob van Broekhoven, gecommitteerde raad of Holland, for Holland;

- Reinier Pauw, burgomaster of Amsterdam, for Holland;

- Pieter Jansz. Schagen, vroedschap of Alkmaar, for Holland;

- Albrecht Bruinink, secretary of Enkhuizen, for Holland;

- Adriaan Mandemaker, representative of the First Noble of Zeeland,[Note 14] for Zeeland;

- Jacob Schotte, burgomaster of Middelburg, for Zeeland;

- Adriaan Ploos, pensionary of Utrecht, for Utrecht;

- Anselmus Salmius, pensionary of Utrecht, for Utrecht;

- Johan van de Zande, justice, Hof van Friesland, for Friesland;

- Rink Aitsma, burgomaster of Leeuwarden, for Friesland;

- Volkert Sloot, drost of Vollenhove, for Overijssel;

- Johan van Hemert, burgomaster of Deventer, for Overijssel;

- Goossen Schaffer, pensionary of Groningen city, for Groningen;

- Schuto Gokkinga, pensionary of the Ommelanden, for Groningen.[32]

Grotius in his Verantwoordingh, written after he had escaped to France, accused many members of the court of lack of impartiality, or even personal hostility to the defendants[33] Van den Bergh, after research in the Nationaal Archief of which he was the Chief Archivist at the time, published a brochure in 1876 attempting to refute this. He tells us that many members of the court, especially those nominated by the States of Holland had made excuses to recuse themselves, but in vain. For instance, Kromhout pointed out that he had close commercial connections to Oldenbarnevelt and Hogerbeets, and Kouwenburg, that he was closely related to the wife of Grotius. That would normally have disqualified them as judges, but the Hof van Holland overruled these objections. Junius apparently had to be threatened with loss of his seat in the court and a heavy fine to convince him to acquiesce in his appointment. Similarly, Duyck had strenuously protested his appointment as fiscal according to the minutes of the States of Holland of 14 November 1618. The other Holland judges had also tried to decline the appointment, according to the minutes of the States of Holland of 31 January 1619.[34]

The interrogations

This improvised court used the rules of criminal procedure that were usual for the Hof van Holland, evidently because the officials of the court were most familiar with those. As usual in an extraordinaris procedure the proceedings consisted of a number of interrogation sessions with the defendants that probably may best be compared to depositions, though the defendants were not sworn in this case. The interrogations were held in a large room on the same floor as the rooms of the defendants. There exists a letter from ambassador Carleton in which he describes that room. He tells us that three sides of the room were lined with chairs for the judges. In the center of the room there was a table for the fiscals and the clerk. The prisoner sat in an (uncomfortable) chair in front of that table (though Oldenbarnevelt got a chair with a back, as a concession to his age)[35] The defendants did not have the right to be represented by counsel, but as they all were among the best legal minds in the country, this was not really a problem.

The interrogation session consisted in the fiscal asking a number of prepared questions of the prisoner. His answers were then noted down in summarized form by the clerk in a proces-verbaal (deposition) that the defendant signed at the end of the session. This deposition was formally considered a confession (though judging from the contents the defendants "confessed" very little). From Grotius' Memorie van mijn Intentiën en notabele bejegening (Memorandum of my Intentions and noteworthy treatment),[36] written after the trial during his incarceration in Loevestein Castle, we know that he often disagreed with the summation of his words noted down by clerk Pots, though he sometimes relented and signed anyway.[37] Presumably this also occurred in the interrogations of the other defendants.[38] We also know from Grotius' memorandum that not everything was noted down, but that the judges sometimes tried to pressure him "in the margin" of the session to admit things that were not asked in the formal session. In other words, the official record may not always reflect the real conversation adequately, certainly as to the tone used and threats uttered.[39]

It is nothing short of miraculous that so much of the trial record has been preserved. As Fruin writes, the proceedings and the record were intentionally kept secret, even though publication might have been in the public interest. Only the verdicts and sentences were eventually published, but everything else disappeared into the archives. For centuries the only record published was Grotius Verantwoordinghe or Apologia, that he published after his escape, from the safety of exile in France in 1622.[40] These official records were not even published during the First Stadtholderless Period when the government of the day would have had a field day from a propaganda perspective. Around the turn of the 18th century Brandt published hisRechtspleging[41] that contained material that had become available in the latter part of the 17th century. But most of the material only saw the light of day in the 19th century when historians like Fruin himself obtained access to the official archives.[42]

The first to be examined in early September 1618 was Ledenberg. He was hard pressed by his personal enemy the Utrecht fiscal van Leeuwen (according to some with threats of torture, though this was officially denied in a resolution of the States General) and this treatment caused him to commit suicide by slitting his throat with a bread knife on 28 September 1618 (so after two weeks).[43] According to the suicide note in the French language that he left, that was referred to in his verdict, he hoped with this desperate act to halt the trial (a not unreasonable expectation) and thereby to prevent a sentence of forfeiture of his assets.[44] But the judges had his body embalmed and retained it until his "execution" which took place posthumously after his conviction on 15 May 1619[43]

From 1 October 1618 Grotius and Hogerbeets were subjected to a number of interrogations that occurred in "bursts" till 23 January 1619 and resumed after 4 February till mid April 1619[45] Oldenbarnevelt had to wait till 15 November 1618 before his interrogations started. He answered 335 questions in the period till 30 November 1618. There was a second series of sessions from 7 to 17 March 1619. In these sessions 242 questions were asked and answered. There was a third series of sessions before 14 April 1619, but the record of these interrogations has not been preserved.[46] Oldenbarnevelt was the only defendant who was given the opportunity to address the full court with a long speech in his defense, beginning on 11 March 1619 that took him three days to finish, but this was considered just another form of "confession", not a formal defense pleading.[47]

The many questions were asked in a somewhat haphazard fashion, possibly to disorient the defendants and to trick them into inconsistencies. There were a number of "themes" that give some insight into what the interrogators were looking for:

- the opposition against the convocation of a National Synod;

- the recruitment of the waardgelders, authorized by the Sharp Resolution, and the "private oaths" that these soldiers had to swear to the local authorities;

- the "libelous" rumors that had been disseminated, accusing Maurice of "aspiring to sovereignty" during his armed excursions against cities like Den Briel and Nijmegen in the Fall of 1617;

- the Declaration of Haarlem of January 1618;

- the protest of "Breach of Union";

- the "conspiracy" with the Utrecht commissioners at the house of Uittenboogaart to "suborn" them not to hand over their message to Maurice in June 1618;

- the mission of Hogerbeets and Grotius to Utrecht to try to ward off the disbandment of the waardgelders in July 1618.[48]

In view of the fact that the defendants were not allowed to communicate among themselves and were held incommunicado, it is remarkable that they appear to have answered the questions in a similar way. The first thing they did when the interrogations started was to question the authority of the court in a polite manner and to demand to be tried before a competent court under the jus de non evocando.In regard to the main themes of the questions summed up above they referred to the "accepted constitutional maxims" like the absolute sovereignty of the States of Holland and the denial of a residual sovereignty of the States General; the untrammeled competence under art. XIII of the Union of Utrecht for the States of Holland to regulate religious affairs as they saw fit, without interference by other provinces, let alone the States General; precedent for the recruitment of waardgelders for maintaining of the public order, going back to 1583, without any objection from the States General; denial that any of them had intended to libel Maurice, but that Oldenbarnevelt just had expressed concern that others would have liked to elevate the Prince to the status of monarch; a claim that there had been a "pre-existing Union" between Holland and Utrecht, which was not contrary to the prohibition in art. X of the Union of Utrecht of concluding separate treaties with foreign states; denial that any secret meetings between the eight Remonstrant cities in the States of Holland to "pre-cook" the Sharp Resolution had occurred; denial that the conversations with the Utrecht delegates in June 1618 had a sinister intent; and in general the contention that none of the defendants had done anything without the consent or the express order of their masters, the States of Holland; and finally that they had acted in the legal defense of the privileges and rights of the States of Holland.[49] Oldenbarnevelt himself denied vehemently all accusations of corruption and of attempts on his part to favor the enemy.[50]

Intendits and Verdicts

The plethora of facts in the several processen-verbaal of the interrogation sessions was unmanageable for the judges, also because the questions and answers were presented in a haphazard fashion, jumping from one subject to another, without an easily discernible "narrative" that people could make head or tail of. One could not expect from the judges that they would wade through this sea of verbiage, check versions of facts against one another, discern what was important and what was not at first glance, and most importantly, interpret the facts in view of the law. Someone had to collate the statements, order them in a coherent whole, and preferably make some legal sense of them. No wonder then that the court took recourse to the civil-law instrument of the intendit: an exposition of the case for the plaintiff (the prosecution) with the evidence to prove the truth of it. The team of fiscals must have set to work in mid-April 1619, after the interrogations were finished. They came up with three separate documents (one for each surviving defendant) two of which are reproduced in our sources: Van den Bergh for Oldenbarnevelt and Fruin for Grotius.[51] These documents took the form of series of numbered "articles", which were intended as steps in a logical argument, allowing reasoning from premises to conclusions. Each article is given a helpful comment as to its status. Next to the factual statements a reference to the place in the depositions of the defendants or of witnesses is given, or the notation notoir (in case the statement is deemed to be "self-evident" or "of general knowledge") is placed. Sometimes a statement is marked negat in case the defendant denies it (in which case additional evidence is referred to). Conclusions or inferences are marked Illatie (Illation[Note 15]).[52]

The intendit for Oldenbarnevelt had no less than 215 articles; that of Grotius 131 (though in the 131st article reference is made to the intendit against Hogerbeets for a rebuttal of a number of excuses both defendants had made in the case of the mission to Utrecht in July 1618). They both start with a similarly worded article:

First that he, prisoner, instead of helping the United Netherlands keep in the tranquility, peace, and unity, that they had obtained through the Truce, he has so helped promote and favor the current troubles and dissensions, that because of that the aforesaid tranquility and unity, in religion and public order, have been troubled altogether, as will become apparent from what follows hereafter.[Note 16]

Thereafter the intendits diverge in the details, though the "themes" that were already discernible in the interrogations return in the grouping of the articles. Both Oldenbarnevelt and Grotius are first taken to task on their "misdeeds" in the matter of the suppression of the Counter-Remonstrants and their opposition to the convocation of the National Synod. Then, under the heading Politie (Public order) the fiscals delve deeply into the way the Sharp Resolution was brought about (through alleged conspiracy between the eight cities in the States of Holland majority at the home of Oldenbarnevelt) and what its consequences were; the allegedly illegal oaths the waardgelders were made to swear; the role of the defendants in thwarting Maurice's attempts to change the governments of several cities (especially the case of Oldenbarnevelt warning the burgomasters of Leiden that Maurice was about to pay them a visit with the advice to close the city gates against him). The Oldenbarnevelt intendit has a group of articles about his alleged corrupt dealings during the Truce negotiations and the way he had allegedly tried to weaken the stance of the government and favor the enemy in these negotiations. There are also a number of allegations about attempts to slander Maurice to sow dissension and through that to weaken the country.[Note 17] Grotius is especially taken to task in the matter of the "conspiracy" with the Utrecht delegates at the home of Uittenboogaart in June 1618, and in the matter of the mission to Utrecht in July 1618 and the attempts to thwart the disbandment of the waardgelders there, culminating in the seditious advice to close the Utrecht gates against Maurice's troops (in which Oldenbarnevelt also played an alleged role) and in the alleged attempt to suborn mutiny by the commanders of the States Army garrison in Utrecht.[53]

Several historians (Uiterhoeve, Den Tex) have taken the fiscals posthumously to task for the way they took statements of the defendants in their depositions out of context, and twisted their meaning (even more than griffier Pots had already done) in an attempt to further their own argument. It was made to appear as if the defendants had thereby "confessed" to the allegations, whereas they had anything but.[54] So one could quip that the fiscals "intendunt veritas".[Note 18]

But there is a more important criticism possible, if one analyzes the intendits from a legal perspective. It transpires that (with a few important exceptions, such as the alleged conspiracies and the alleged corruption) the facts in the case were not in dispute. But the interpretation of the facts was very much so. This applies both to the imputed intent of the defendants, and to the criminality of the alleged acts at the time they were committed. An important maxim of criminal law has since the Middle Ages been that one can only have a criminal intent if the crime exists as a crime at the time it is committed (Nulla poena sine lege). To give an example: the defendants opposed the convocation of a National Synod with an appeal to art. XIII of the Union of Utrecht which states in part : "As for the matter of religion, the States of Holland and Zeeland shall act according to their own pleasure ... and no other Province shall be permitted to interfere or make difficulties..."[Note 19] Their political opponents wanted to put this constitutional provision aside with an appeal to "necessity" or raison d'etat and eventually managed to prevail in the political dispute by majority vote in the States General. But this made the opposition of the States of Holland not a crime before this vote had been taken (even if one assumes that the majority decision was itself completely legal, which the defendants would deny). Another example is the matter of the hiring of waardgelders by the Holland cities. The fiscals asserted that this was contrary to art. I of the Union, but Oldenbarnevelt countered, quoting precedent, that it had never been so interpreted before, so it could not be considered a crime.[55]

In other words, the dispute was actually more about points of law than about facts. In that case the Court would have been better served by the alternative to the intendit in Holland civil law, the appointement bij memoriën, in which the parties exchanged memorandums about the interpretation of the law-in-dispute before the court. But in this case the defendants not even got the chance to see the intendits or comment on them as one would expect, as far as we can now affirm: neither Grotius in his Memorandum about the treatment he received, nor Jan Francken (Oldenbarnevelt's valet) in his memoir about Oldenbarnevelt's days in prison[56] makes mention of the intendits. Which makes clear that they did not play a role in the defense of the prisoners. In any case, neither defendant has signed the intendits as proof that they confirmed the assertions made in them, so the intendits cannot be quoted as part of the "confession" of the prisoners.

Which makes one wonder what role they actually played in the trial. It is possible that they were accepted by the Court as "proof" in the case, like an intendit might be accepted in a civil case. But then it could not be used in place of a confession as required for a death sentence.

However, this may be, one would expect that the court would have "cribbed" from the intendits when writing the verdicts of the case. But this appears to have been the case in only a limited sense if one compares the texts of the intendits with the eventual verdicts. It looks as if the intendits only provided (rather tedious) filler material (obiter dicta) between the preamble of the verdicts and the rationes decidendi before the sentence.[Note 20] But both the preamble and this final part seem to contain the really important part of the legal reasoning in the verdict. And they do not appear anywhere in the texts of the intendits, so it seems likely that they have a different author, who introduced a new element in the reasoning of the Court, after the intendits had been completed.

In all three cases their wording is remarkably similar. Both preambles contain the (demonstrably false) assertion that the verdicts are based on the confession of the convicted prisoner "without torture and fetters of iron", which is the standard phrasing, but is untrue as no record exists of the prisoners having confirmed their confession in open court, as the phrase suggests. Hence the evident indignant surprise of Oldenbarnevelt at the reading of the verdict in his case.[57]

All preambles contain the following phrase:

... it is permitted to nobody, to violate or sever the bond and fundamental laws upon which the government of the United Netherlands is founded, and these countries through God's gracious blessing having until now been protected against all violence and machinations of her enemies and malignants he the prisoner has endeavored to perturbed the stance of the religion, and to greatly encumber and grieve the Church of God, and to that end has sustained and employed maxims exorbitant and pernicious to the state of the lands...[58]

Damen comments that here the treason definition from the treason statutes of the States of Holland and the States General of the late 1580s and early 1590s is extended from "perturbation of the public order" to "perturbation of the stance of the religion" and hence of the Church. In other words, the court could have convicted the defendants for "perturbing public order" as a consequence of "sustaining pernicious maxims" (the Remonstrant theses that had at the time recently been condemned as "heretical" by the Synod of Dort), but instead the court opted for declaring the "perturbation" of the Church as itself "treasonous." This amounted to "legislating from the bench" as this was an entirely new element of the Dutch law of treason as it existed since the 1590s.[59][Note 21]

Of course, "making new law" by setting a new precedent in interpreting the law is nothing new in civil law, but in criminal law it flies in the face of nulla poena sine lege if the new precedent is immediately applied with retroactive force to the case in hand. Oldenbarnevelt for that reason complained in his conversation with Antonius Walaeus in the night before his execution:

That he did not want to accuse the judges, but that he now came into a time in which people used other maxims, or rules of government in the state, than in his own time, and that the judges couldn't really condemn him on that basis.[Note 22]

Curiously, the legal reasoning in the rationes decidendi at the end of the verdict, just before sentence is pronounced is completely different. In all three cases (only the verdict for Ledenberg is different) the following wording is used:

From this, and from all his other machinations and conspiracies it has followed that he has erected States within States,[Note 23] governments within governments, and new coalitions constructed within and against the Union; there has become a general perturbation in the state of the lands, both in the ecclesiastical and the political, which has exhausted the treasury and has brought about costs of several millions; has instigated general diffidence, and dissension among the allies, and the inhabitants of the lands; Has broken the Union, rendered the lands incapable of their own defense, risking their degeneration into scandalous acts, or their complete downfall. Which ought not to be condoned in a well-ordered government, but ought to be punished in an exemplary way.[60]

In other words, according to Damen, the conviction rested on the following points:

- conspiring against the United Provinces with his own political faction;

- disturbing the ecclesiastical and political state of the lands;

- exhausting the treasury;

- putting the provinces at odds with one another, having thereby broken the union, having thereby endangered the Union.[61]

The difference between the reasoning in the preamble and here is that the "perturbation" of the Church is only one of the elements, and that the main element now has become the political undermining of the Union. These points form a curious mixture of the treason statutes of the States General (points 2 and 3, Acts of 12 April 1588 and 17 April 1589) and of the States of Holland (Committing acts that go against the common peace and public order). In other words, the judges took two elements from the statutes of the States General of 1588 and 1589 and embedded them in the legal framework of the treason statutes of the States of Holland. Again this is "new law" being applied retroactively and therefore contrary to nulla poena sine lege. But the new synthesis brought about a considerable change in the law of treason in the Republic and therefore was of lasting significance.[62]

But the verdict had constitutional consequences also. It recognizes the Union as the "injured party" in the trial and puts down the coalition of the eight "Arminian" cities that Oldenbarnevelt led, as a "rival faction" aimed at undermining the United Netherlands. Consequently, it derogates from all legitimacy Oldenbarnevelt's actions might have had and "construes" the "Generality" of all Provinces in the States General as the sole highest power (sovereign) legitimately exercising political power, and no longer the States of the several provinces. By acting as if this new constitutional construction was the positive law of the land, the constitution was materially changed.[63]

The punishments

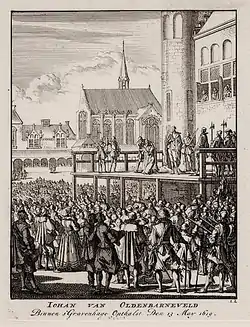

Oldenbarnevelt was the first to be sentenced. The fiscals van Leeuwen and de Silla arrived in the late afternoon of Sunday 12 May 1619 in his room to announce that he had received the death sentence and that he would be executed the next morning. The old man was completely surprised as he had expected to get another chance to address the court, so he exclaimed several times "The death sentence! The death sentence" in obvious distress. The next 15 hours he spent first writing a farewell letter to his wife, in which he was interrupted by two Counter-Remonstrant preachers Walaeus and Lamotius, who had been sent to sustain him spiritually in his last hours. So he spent the night conversing about theological subjects[Note 25] and in this conversation he refused to confess to his guilt. But he asked the intercession of Walaeus with Maurice, one of whose residual prerogatives as a stadtholder was the power of pardon. However, as Oldenbarnevelt refused to admit his guilt, Maurice declined this. Similar entreaties by the French ambassador and Louise de Coligny, Maurice's stepmother, also had no result. The next morning, after a sleepless night, Oldenbarnevelt was marched to the Rolzaal (Audience Chanber) of the Hof van Holland on the floor of the building below his room, where the court was assembled. Around 9 in the morning the verdict in his case was read to him by griffier Pots. He was clearly not pleased with what he heard, several times trying to interrupt with protests. After the reading had finished Oldenbarnevelt complained about the fact that he was not only sentenced to be decapitated by the sword, but that he also was deprived of the possibility to leave his property to his wife and children, because in addition he had been sentenced to forfeiture of his assets. He exclaimed "Are these the wages for 43 years of faithful service to the country?". He also may have said: "This verdict is not in accordance with my testimony", or "To arrive at this verdict the Lords have drawn all kinds of conclusions from my statements that they should not have inferred." President de Voogd replied: "You have heard the verdict, so now we can proceed with the execution."[64]

Then Oldenbarnevelt, accompanied by his valet Jan Francken, who had shared his incarceration since the previous August, was led through the building of the Ridderzaal, leaving by the front entrance. There he found a scaffold that had been hastily constructed during the night and the waiting executioner, Hans Pruijm, the executioner of the city of Utrecht, who must have traveled through the night to arrive in time,[65] and the Provost marshal of the States Army, who was in charge of the execution. Oldenbarnevelt then removed his top clothes, helped by Francken, and meanwhile in a loud voice declaimed his innocence to the waiting crowd:

Men, do not believe that I am a traitor. I have always lived piously and sincerely, like a good patriot, and so I will die also - that Jesus Christ may lead me.[66]

. His very last words were to his valet Jan Francken who was understandably distressed: "Maak het kort, maak het kort" (Be brief, be brief). Then he knelt before a heap of sand on the scaffold, staying upright (there was no block) and drew his nightcap over his eyes. The executioner separated head and body with one fell swoop of the executioner's sword.[66]

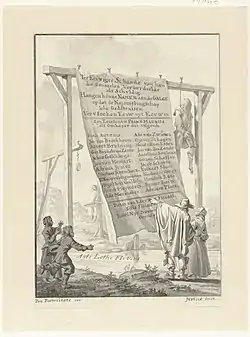

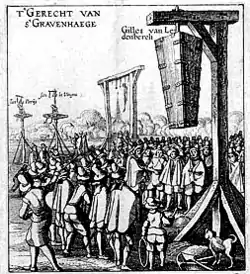

The next sentence was pronounced on 15 May 1619 over Gilles van Ledenberg, who had been dead since the end of the previous September. Obviously, he could not be executed, but the judges declared in the verdict that he was "worthy of death" and would so have been sentenced if he had been alive. His "exemplary sentence" was that his embalmed body would be hung from a gibbet in its coffin. He also was sentenced to forfeiture of assets.[67]

Finally it was the turn of Hogerbeets and Grotius. Both were sentenced on 18 May 1619. Both received sentences of eeuwigdurende gevangenisstraf (perpetual imprisonment) in the quaint phrasing from the Carolina (the term "life imprisonment" was not yet used) and of forfeiture of their assets. Both were transported to Loevestein Castle, which was then the state prison for high-value political prisoners.[68][Note 26]

Aftermath

In the Resolution register of the States of Holland the following entry was made on 13 May 1619 by their newly-appointed secretary Duyck (one of the fiscals in the trial):

Remember this. Today was executed with the sword here in The Hague, on a scaffold thereto erected in the Binnenhof before the steps of the Great Hall, Mr. Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, in his life Knight, Lord of Berkel, Rodenrijs, etc., Advocate of Holland and West Friesland, for reasons expressed in the sentence and otherwise, with confiscation of his property., after he had served the state thirty-three years two months and five days since 8 March 1586; a man of great activity, business, memory and wisdom - yes, extraordinary in every respect. He that stands let him see that he does not fall,[Note 27] and may God be merciful to his soul. Amen.[69]

Oldenbarnevelt was buried in the crypt below the Chapel on the Binnenhof. Attempts to give him a burial elsewhere were not successful even many years later, so it seems likely that his bones still rest there.[70]

Oldenbarnevelt's wife Maria van Utrecht, was the principal victim of the forfeiture-of-assets sentence. She and her family tried to quash it and at first seemed successful in their suit before the Hof van Holland, because Oldenbarnevelt had not been sentenced for crimen laesae majestatis which carried an automatic forfeiture penalty (the term is nowhere used in the verdict). The treason statutes on the basis of which he had been condemned did not carry such an automatic penalty, which made the sentence potentially unsafe. To "remedy" this omission and to frustrate the lawsuit a meeting of the former judges (those that were still alive at that time) was convened by former griffier Pots on 6 June 1620, and the judges stated (as minuted by Pots) that "... at the time of the determination of the verdict they were of the opinion, and have interpreted the case in the sense, that the aforesaid Jan van Oldenbarnevelt and the other prisoners and condemned persons have committed, or have instigated, the crimen laesae majestatis"[71] Consequently, the petition to quash the forfeiture was refused by the court. Oldenbarnevelt's real estate was auctioned off in 1625 and the proceeds spent to pay for the cost of the trial. Oldenbarnevelt's wife lost her house in The Hague and had to move in with her in-laws.

Oldenbarnevelt's sons Groenevelt and Stoutenburg were involved in a conspiracy to assassinate Maurice in 1623. Groenevelt was sentenced to death for his part in the plot and beheaded at the Groene Zoodje (the usual place of public execution in The Hague, outside the Gevangenpoort jail). Stoutenburg managed to escape and went into exile. Maria van Utrecht pleaded for mercy with Maurice. He asked her why she had refused to plead for her husband's life. She replied that her husband was innocent, while her son was guilty.[72]

The corpse of Ledenberg was duly hanged in its coffin on 15 May; it was displayed for three weeks, until 5 June, when it was removed to be buried near the church of Voorburg. But the same night a mob disinterred it and threw it in a ditch. Eventually the body was buried in a chapel belonging to Ledenberg's son-in-law.[73]

Grotius and Hogerbeets were incarcerated in Loevestein Castle. Grotius did not stay there very long, thanks to the ingenuity of his resourceful wife Maria van Reigersberch, who helped him escape in a book chest.[74] They fled to France, where Grotius wrote his Apologia, published in 1622. In it he took the verdict apart, in detail criticizing the elements of the rhetorical flourish (i.e. exergasia) in the verdict: "States within States" (his political opponents had been the first to form political factions, meeting in secret, so why were they not prosecuted?); "governments within governments" ("We have in Holland had a high government, according to the old laws, customs and Union, leaving to the States General the government in matters of war, but binding the cities together so that they can take resolutions concerning the public will, in my opinion what a government normally does"); "new coalitions constructed within and against the Union" ("This is mendacious. We base ourselves on the union made, first between Holland and Zeeland, and later extended to Utrecht, in which the sovereignty was reserved to the provinces also on the point of regulation of the religion ... We have limited ourselves to the compliance with existing unions, not to the making of new ones")[75]

Hogerbeets was not as lucky. Like Grotius' wife, his wife was allowed to share his cell in Loevestein. However, she fell ill and died on 19 October 1620. It took the jailers three days to remove the body, so Hogerbeets was forced to stay in the room with the corpse, which caused him much distress. During his incarceration he was able to write a law manual, entitled: Korte inleidinge tot de praktyk voor de Hoven van Justitie in Holland (Short introduction to the practice of law before the courts of justice in Holland). He remained incarcerated until the new stadtholder Frederick Henry, who was appointed after Maurice's death in 1625, allowed him to retire to a home in Wassenaar, where he remained under house arrest until his death in September 1625.[76]

The trial also made news in other countries. In England a play by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger, entitled The Tragedy of Sir John van Olden Barnavelt was performed by the King's Men at the Globe Theatre in 1619.

Another artist who was inspired by the trial was Joost van den Vondel, who wrote his allegorical play Palamedes (1625) with Oldenbarnevelt's fate in mind. He also wrote a number of polemical and satirical poems, among which Op de jongste Hollandsche Transformatie (1618), Geusevesper (1619) and Het stockske van Joan van Oldenbarnevelt(1630).

Notes

- These "maxims" would become the bones of contention during the crisis that led up to the trial and would be changed during the trial, but before these events they were generally accepted; Cf. Uitterhoeve, p. 186

- This word is a plurale tantum in both Dutch (Staten) and English and refers to the medieval representations of the estates of the Realm before their feudal lords. It should not be confused with the concept of State (polity)

- Such auxiliary mercenary troops were generally referred to as waardgelders (after the German word Wartegelt, retainer). They were usually employed when the States Army was away on campaign from its usual garrison duty

- The placard did not prohibit all discussion about the controversy, but limited it to the universities and learned treatises written in Latin; Cf. Den Tex, p.

- Of which the Republic remained a part until the Peace of Westphalia of 1648

- The difference is important, because we will see that in the verdict in the trial against Oldenbarnevelt c.s. no mention is made of crimen laesae majestatis, but the terminology of the treason statutes of the States of Holland and the States General is used. It is true that this "omission" was later "remedied" by having the still-living judges declare that "they had always intended to convict for laesae majestatis", but that was a subterfuge, because otherwise the sentence of asset forfeiture would have been invalid. Cf. Fruin, p. 353

- His house stood at the location of what is now Kneuterdijk 22, next to the Kneuterdijk Palace which did not exist at the time.

- Here used in the sense of safe conduct; the actual term used was sauvegarde.

- The Dutch system of justice did not have Habeas corpus as such, but there were similar writs against arbitrary arrest.

- The text of the pamphlet is printed in full in Brandt, pp.2-3

- Who was a member of the Council of State under the Treaty of Nonsuch.

- Still, there was precedent for appointing delegated judges and taking away the defendant from his own judges, and Oldenbarnevelt had been involved in this. This was the 1587 case of the treason trial in Leiden of colonel Cosmo de Pescarengis where a commission of delegated judges was employed; Cf. Motley, J.L. (1900). "The writings of John Lothrop Motley, Volume 8". Google Books. Harper and brothers. p. 158. Retrieved 2 April 2019. Van den Bergh remarks that Oldenbarnevelt could be deemed a servant of the States General, as he had for a long time formulated the foreign policy of that body, which would make him subject to its jurisdiction; Cf. Van den Bergh (1876), pp. 12-13

- In protocolary order, with the Duchy of Gelderland first and Groningen last.

- This was the Prince of Orange

- The act of drawing a conclusion

- Eerstelijck, dat hij gevangene, in plaetse van de Geunieerde Nederlanden te helpen houden in de ruste, vrede en eenicheyt, die zij deur de Trefves hadden vercregen, heeft die tegenwoordige swaerigheden ende dissentiën soo helpen voorderen ende foveren, dat daardeur die voorsz. ruste ende eenicheyt, soo in de religie als politie, t'eenemael is getroubleert geworden, blykende uyt hetgene hiernaer volgt; Fruin, p. 306

- Maurice had vehemently denied "striving after sovereignty" and indeed he never tried to take up the monarchy. One positive effect of these slanders may therefore have been that the Republic remained a republic and kept the stadtholder subordinate to the States until the end of its days.

- The Latin third-conjugation verb intendere has many meanings. Valid translations are "to set", as in cursum intendit: "he sets a course", but also "to stretch", as in intendit veritas: "he stretches the truth"

- "As for the matter of religion, the States of Holland and Zeeland shall act according to their own pleasure, and the other Provinces of this Union shall follow the rules set down in the religious peace drafted by Archduke Matthias, governor and captain-general of these countries, with the advice of the Council of State and the States General, or shall establish such general or special regulations in this matter as they shall find good and most fitting for the repose and welfare of the provinces, cities, and individual Members thereof, and the preservation of the property and rights of each individual, whether churchman or layman, and no other Province shall be permitted to interfere or make difficulties, provided that each person shall remain free in his religion and that no one shall be investigated or persecuted because of his religion, as is provided in the Pacification of Ghent"; Cf. English translation on "The Union of Utrecht". Constitution Society. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- An exception in the other direction where the verdict goes into more detail than either the intendit or the previous interrogations is the case of the verdict against Grotius in the matter of an alleged abuse of power in the baljuwschap (bailiwick) of Schieland, near Rotterdam, where the Rotterdam magistrates had made a bye-law prohibiting church meetings outside the approved churches on the basis of the Tolerance Resolution. Cf. Fruin, First interrogation of Grotius, par. 40 and Intendit, article 19

- Damen adds that this came close to the Habsburg use of crimen laesae majestatis divinae, but that the court did not define the perturbation of the Church as laesio majestatis. In fact, the crimen laesae majestatis is never mentioned in the verdict as a whole; Cf. Damen, p. 61

- Dat hij de rechters niet wilde beschuldigen, maar dat hij nu quam in een tijdt in den welken men andere maximen, of regelen van regeering in den Staet hield, dan in den tijdt in welken hij was geweest, en dat hij daarom van de rechters qualijk konde geoordeelt worden. Cf. Brandt, p. 181

- In view of the Latin translation of this passage in the verdict: ut inter Ordines alios Ordines, this clearly refers to "States" as in "States of Holland", and not to "states" in the usual sense; Cf. Damen, p.65

- In the background the Chapel with its steeple is visible, where Oldenbarnevelt would be buried in the crypt.

- Walaeus reported later that on the subject of the predestination controversy Oldenbarnevelt turned out to be very close to the Counter-Remonstrant standpoint. This should cause little surprise as he had always steered clear of endorsing either standpoint, and just tried to promote tolerance; Cf. Blok, p. 474

- Like Oldenbarnevelt Hogerbeets complained after the verdict in his case had been read that he had not confessed to the crimes he had been charged with, and demanded a rectification. When he was told to shut up he bitterly quoted Horace: Hic murus aheneus esto, nil conscire sibi, nulla palescere culpa (let this be your brazen wall of defense, to have nothing on your conscience, no guilt to make you turn pale); Cf.Stijl, Stinstra, Levensbeschrijving, p. 297

- This is a literal translation of the Dutch version of 1 Corinthians 10:12, which reads in the KJV: "Wherefore let him who thinketh that he standeth take heed lest he fall", but the Dutch version quoted here cannot be the version from the Statenvertaling, because that translation of the Bible had only just been ordered by the States General at this time.

References

Citations

- Uitterhoeve, p. 186

- Israel, pp. 399-405

- Israel, pp.421-432

- Israel, pp. 433-441

- Israel, pp. 441-443

- Israel, pp. 443-447

- Motley, pp. 41-43

- Fruin, pp. 299-305

- Israel, pp. 447-449

- Israel, p. 449

- Le Bailly, p. 242

- Damen, p. 22

- Damen, p. 21

- Damen, pp. 29-31, 34-35

- Damen, p. 35

- Damen, pp. 36-40

- Uitterhoeve, p. 93

- Le Bailly, pp. 176-180

- Uitterhoeve, p. 141

- Le Bailly, pp. 148-150, 155, 308

- Wassink, J.F.A. (2005). Van stad en buitenie: Een institutionele studie van rechtspraak en bestuur in Weert 1568-1795. Google Books (in Dutch). Uitgeverij Verloren. p. 120. ISBN 9065508503. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Uitterhoeve, p. 81

- Uitterhoeve, pp. 81-90

- Den Tex, p. 251

- Den Tex, p. 245

- Uitterhoeve, p. 86

- Den Tex, p. 244

- Damen, p. 53

- Le Bailly, pp. 38, 46

- Uitterhoeve, p.81

- Uitterhoeve, p. 107

- Brandt, pp. 66-67

- Grotius, pp. 155-157

- Van den Bergh (1876), pp. 18-20

- Uitterhoeve, pp. 109-110

- Fruin, pp. 1-80

- Fruin, p. 55

- Uitterhoeve, p. 110

- Fruin, pp. 44-45, 51-54

- Grotius, passim

- Brandt, passim

- Fruin, pp. v-ix

- Uiterhoeve, p. 138

- Sententie Ledenberg, passim

- Fruin, pp.104-124, 230-257

- Uitterhoeve, p.109

- Den Tex, p. 254

- Den Tex, p. 250

- Uitterhoeve, pp. 111-137

- Uitterhoeve, pp. 131-137

- Van den Bergh (1875), pp. 1-61; Fruin, pp. 306-336

- Uitterhoeve, p.141

- Uitterhoeve, pp. 142-146

- Uitterhoeve, p. 142

- Uitterhoeve, pp. 112-113

- Francken, J. (2005). Rosenboom, T. (ed.). Het einde van Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, beschreven door zijn knecht Jan Francken (in Dutch).

- Sententie Oldenbarnevelt; Sententie Hogerbeets; Fruin, p. 337

- Damen, p. 60; Fruin, p. 337-338

- Damen, p. 61

- Damen, p. 62

- Damen, pp. 62-63

- Damen, p. 63

- Damen, pp. 65-66

- Uitterhoeve, pp. 151-161

- Snijder, C.R.H. (2014). Het scherprechtersgeslacht Pruijm/Pfraum, ook Prom/Praum/Sprong genoemd (Meester Hans Pruijm, executeur van Johan van Oldenbarnevelt), deel 1, in: Gens Nostra 69 (in Dutch). pp. 488–500.

- Uitterhoeve, p. 161

- Sententie Ledenberg

- Sententie Hogerbeets; Fruin, p. 338

- Motley, p. 231

- Uitterhoeve, p.170

- Uitterhoeve, p. 179

- Uitterhoeve, p. 181

- Aa, A.J. van der, Harderwijk, K.J.R. van, Schotel, G.D.J. (1865). Ledenbergh (Gilles van), in: Biographisch woordenboek der Nederlanden: bevattende levensbeschrijvingen van zoodanige personen, die zich op eenigerlei wijze in ons vanderland hebben vermaard gemaakt. Deel 11 (in Dutch). p. 234.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Blok, p. 477

- Grotius, pp. 280-281

- Stijl, S., Stinstra, J. (1777). Levensbeschrijving van Rombout Hogerbeets, in: Levensbeschryving van eenige voornaame meest Nederlandsche mannen en vrouwen. Deel 4 (in Dutch). pp. 296–304.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Sources

- Bergh, L.Ph.C. van den, ed. (1875). "Intendit of acte van beschuldiging tegen Mr. Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, naar het oorspronkelijke in het rijks-archief met eenige bewijsstukken". Google Books (in Dutch). Nijhoff. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Bergh, L.Ph.C. van den (1876). "Het proces van Oldenbarnevelt getoetst aan de wet". Google Books (in Dutch). Nijhoff. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- Blok, P.J. (1900). "History of the People of the Netherlands: The war with Spain". Google Books. G. P. Putnam's sons. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Brandt, G. (1723). "Historie van de rechtspleging gehouden in ... 1618 en 1619 ontrent ... mr. Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, mr. Rombout Hoogerbeets, mr. Hugo de Groot". Google Books (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Damen, W.W.P. (2017). "Maiestas in the Dutch Republic. The law of treason and the conceptualisation of state authority in the Dutch Republic from the Act of Abjuration to the expiration of the Twelve Years' Truce (1581-1621)". Brussels. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Fruin, R., ed. (1871). "Verhooren en andere bescheiden betreffende het rechtsgeding van Hugo de Groot". Google Books (in Dutch). Kemink en Zn. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Grotius, H. (1622). "Verantwoordingh van de wettelijcke regieringh van Hollandt ende West-Vrieslandt, midtsgaders eenigher nabuyrighe provincien, sulcks die was voor de veranderingh, gevallen inden jare 1618, gheschreven by Mr. Hugo de Groot [...] Met wederleggingh van de proceduren en de sententien, jegens den selven De Groot ende anderen gehouden ende ghewesen". Google Books (in Dutch). Isaac Willemsz. van der Beeck. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Israel, Jonathan (1995). The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-873072-1.

- Le Bailly, M.C. (2001). Recht voor de Raad: rechtspraak voor het Hof van Holland, Zeeland en West-Friesland in het midden van de vijftiende eeuw. Google Books (in Dutch). Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 9070403501. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Motley, J.L. (1902). "The Complete Works of John L. Motley ...: The life and death of John of Barneveldt, vol. II". Google Books. Society of English and French Literature. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Platt, E. (2014). Britain and the Bestandstwisten: The Causes, Course and Consequences of British Involvement in the Dutch Religious and Political Disputes of the Early Seventeenth Century. Google Books. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 9783647550770. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- "Sententie, uyt-ghesproocken ende ghepronuncieert over Rombout Hogerbeetz, ghewesen pensionaris der stadt Leyden, den 18 may, anno 1619, stilo novo". Google Books (in Dutch). Hillebrant Iacobssz. 1619. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- "Sententie, uyt-ghesproocken ende ghepronuncieert over Gielis van Ledenberch, ghewesen secretaris vande heeren Staten van Vtrecht: ende over desselfs cadaver geexecuteert den vijfthienden may, anno sesthien-hondert neghenthien, stilo novo". Google Books (in Dutch). Hillebrant Iacobssz. 1619. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- "Sententie uyt-ghesproocken ende ghepronuncieert over Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, gewesen advocaet van den lande van Hollant ende West-Vrieslant: ende geexecuteert den derthienden may anno sesthien hondert negenthien, stilo novo, op 't Binnen-hof in 's Graven-haghe". Google Books (in Dutch). Hillebrandt Jacobsz. 1619. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Tex, J. den, and A. Ton (1980). "Johan van Oldenbarneverlt". Digitale Bibliotheek van de Nederlandse Letteren (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 March 2019.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Uitterhoeve, W. (2019). De zaak Oldenbarnevelt. Val, proces en executie (in Dutch). Vanbilt. ISBN 978-94-6004-411-3.

- Wijne, J.A. (1859). "Het stuk der Waardgelders in de provincie Holland, hoofdzakelijk gedurende het ministerie van Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, in De gids: nieuwe vaderlandsche letteroefeningen,July and August". Google Books (in Dutch). pp. 111–149, 232–284. Retrieved 11 March 2019.