Posthumous execution

Posthumous execution is the ritual or ceremonial mutilation of an already dead body as a punishment. It is typically performed to show that even in death, one cannot escape justice.

Dissection as a punishment in England

Some Christians believed that the resurrection of the dead on Judgment Day requires that the body be buried whole facing east so that the body could rise facing God.[1][2] If dismemberment stopped the possibility of the resurrection of an intact body, then a posthumous execution was an effective way of punishing a criminal.[3][4]

In England Henry VIII granted the annual right to the bodies of four hanged felons. Charles II later increased this to six ... Dissection was now a recognised punishment, a fate worse than death to be added to hanging for the worst offenders. The dissections performed on hanged felons were public: indeed part of the punishment was the delivery from hangman to surgeons at the gallows following public execution, and later public exhibition of the open body itself ... In 1752 an act was passed allowing dissection of all murderers as an alternative to hanging in chains. This was a grisly fate, the tarred body being suspended in a cage until it fell to pieces. The object of this and dissection was to deny a grave ... Dissection was described as "a further terror and peculiar Mark of Infamy" and "in no case whatsoever shall the body of any murderer be suffered to be buried". The rescue, or attempted rescue of the corpse was punishable by transportation for seven years.

— Dr D. R. Johnson, Introductory Anatomy.[5]

Examples

- In 897, Pope Stephen VI had the corpse of Pope Formosus disinterred and put on trial during the Cadaver Synod. Found guilty, the corpse had three of its fingers cut and was later thrown into the Tiber.

- Harold I Harefoot, king of the Anglo-Saxons (1035–1040), illegitimate son of Cnut, died in 1040 and his half-brother, Harthacanute, on succeeding him, had his body taken from its tomb and cast in a pen with animals.[6]

- Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, died of wounds suffered at the Battle of Evesham in 1265; his corpse was beheaded, castrated and quartered by the knights of Henry III of England.[7]

- Roger d'Amory (c. 1290 – before 14 March 1321/1322) died following the Battle of Burton Bridge and was then posthumously executed for treason by Edward II.

- John Wycliffe (1328–1384) was burned as a heretic forty-five years after his death.

- Vlad the Impaler (1431–1476) was beheaded following his assassination.

- Jacopo Bonfadio (1508–1550) was beheaded for sodomy and then his corpse was burned at the stake for heresy.

- Nils Dacke, leader of a 16th-century peasant revolt in southern Sweden, was decapitated and dismembered after his death in combat.

- By order of Mary I, the body of Martin Bucer (1491–1551) was exhumed and burned at the Market Square in Cambridge, England.

- In 1600, after the failure of the Gowrie conspiracy, the corpses of John, Earl of Gowrie and his brother Alexander Ruthven were hanged and quartered at the Mercat Cross, Edinburgh.[8] Their heads were put on spikes at Edinburgh's Old Tolbooth and their limbs upon spikes at various locations around Perth, Scotland.[9]

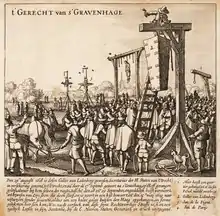

- Gilles van Ledenberg, whose embalmed corpse was hanged from a gibbet in 1619, after his conviction of treason in the trial of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt.

- A number of the 59 regicides of Charles I of England, including the most prominent of the regicides, the former Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, died before the Restoration of his son Charles II in 1660. Parliament passed an order of attainder for High Treason on the four most prominent deceased regicides: John Bradshaw the court president; Oliver Cromwell; Henry Ireton; and Thomas Pride.[10] The bodies were exhumed and three were hanged for a day at Tyburn and then beheaded. The three bodies were then thrown into a pit close to the gallows, while the heads were placed, with Bradshaw's in the middle, at the end of Westminster Hall (the symbolism was lost on no one as that was the building where the trial of Charles I had taken place). Oliver Cromwell's head was finally buried in 1960. The body of Pride was not "punished", perhaps because it had decayed too much.

- Edward Teach (1680–1718), better known as "Blackbeard", was killed by the sailors of HMS Pearl who boarded on his ship, the Adventure. British First Lieutenant Robert Maynard examined Edward Teach's body, decapitated and tied his head to the bowsprit of his ship for the trip back to Virginia. Upon returning to his home port of Hampton, the head was placed on a stake near the mouth of the Hampton River as a warning to other pirates.[11]

- Joseph Warren (1741–1775), a physician and major general of American colonial militas, was stripped of his clothing, bayoneted until unrecognizable, and then he was shoved into a shallow ditch, after he was killed at the Battle of Bunker and Breed's Hill. Days later, British Lieutenant James Drew had Joseph Warren's body exhumed again; his was body stomped on, beaten, decapitated and humiliated on the area, according to eyewitness testimonies.[12][13]

- In 1917, the body of Rasputin, the Russian mystic, was exhumed from the ground by a mob and burned.[14]

- In 1918, the body of Lavr Kornilov, the Russian general, was exhumed by a pro-Bolshevik mob. It was then beaten, trampled and burned.

- In 1966, during the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards stormed the Dingling Mausoleum; thousands of other artifacts were destroyed, and they dragged the remains of the Wanli Emperor and his two empresses to the front of the tomb, where they were posthumously denounced and burned after photographs were taken of their skulls.[15][16]

- The body of General Gracia Jacques, a supporter of François Duvalier ("Papa Doc") (1907–1971), the Haitian dictator, was exhumed and ritually beaten to "death" in 1986.[17]

Notes

- Barbara Yorke (2006), The Conversion of Britain Pearson Education, ISBN 0-582-77292-3, ISBN 978-0-582-77292-2. p. 215

- Fiona Haslam (1996), From Hogarth to Rowlandson: Medicine in Art in Eighteenth-century Britain, Liverpool University Press, ISBN 0-85323-640-2, ISBN 978-0-85323-640-5 p. 280 (Thomas Rowlandson, "The Resurrection or an Internal View of the Museum in W-D M-LL street on the last day) Archived 26 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine", 1782)

- Staff. "Resurrection of the Body". Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- Mary Abbott (1996). Life Cycles in England, 1560–1720: Cradle to Grave, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-10842-X, 9780415108423. p. 33

- Dr D.R.Johnson, Introductory Anatomy Archived 4 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Centre for Human Biology, (now renamed Faculty of Biological Sciences Archived 2 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Leeds University), Retrieved 2008-11-17

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- Frusher, J. (2010). "Hanging, Drawing and Quartering: the Anatomy of an Execution". Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- Henderson 1897, p. 19.

- Juhala 2004.

- Journal of the House of Commons: volume 8: 1660–1667 (1802), pp. 26–7 Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine House of Commons The attainder was predated to 1 January 1649 (1648 old style year).

- Lee, Robert E. (1974). Blackbeard the Pirate (2002 ed.). North Carolina: John F. Blair. ISBN 0-89587-032-0.

- "To John Adams from Benjamin Hichborn, 25 November 1775". National Archives. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- Tourtellot, Arthur Bernon (1959). Lexington and Concord: The Beginning of the War of the American Revolution. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-393-32056-5.

- Rollins, Patrick J. Wieczynski, Joseph L. (ed.). Rasputin, Grigorii Efimovich. The Modern encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet history. Academic International Press. ISBN 0-87569-064-5. OCLC 2114860.

- Becker, Jasper (2008). City of Heavenly Tranquility: Beijing in the History of China. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530997-3, pp 77-79.

- Melvin, Sheila (7 September 2011). ""China's reluctant Emperor"". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Brooke, James; Times, Special to the New York (9 February 1986). "HAITIANS TAKE OUT 28 YEARS OF ANGER ON CRYPT". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

References

- Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1897). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 50. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 15–20.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Juhala, Amy L. (2004). "Ruthven, John, third earl of Gowrie (1577/8–1600)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24371.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)