Tree traversal

In computer science, tree traversal (also known as tree search and walking the tree) is a form of graph traversal and refers to the process of visiting (checking and/or updating) each node in a tree data structure, exactly once. Such traversals are classified by the order in which the nodes are visited. The following algorithms are described for a binary tree, but they may be generalized to other trees as well.

| Graph and tree search algorithms |

|---|

| Listings |

|

| Related topics |

Types

Unlike linked lists, one-dimensional arrays and other linear data structures, which are canonically traversed in linear order, trees may be traversed in multiple ways. They may be traversed in depth-first or breadth-first order. There are three common ways to traverse them in depth-first order: in-order, pre-order and post-order.[1] Beyond these basic traversals, various more complex or hybrid schemes are possible, such as depth-limited searches like iterative deepening depth-first search. The latter, as well as breadth-first search, can also be used to traverse infinite trees, see below.

Data structures for tree traversal

Traversing a tree involves iterating over all nodes in some manner. Because from a given node there is more than one possible next node (it is not a linear data structure), then, assuming sequential computation (not parallel), some nodes must be deferred—stored in some way for later visiting. This is often done via a stack (LIFO) or queue (FIFO). As a tree is a self-referential (recursively defined) data structure, traversal can be defined by recursion or, more subtly, corecursion, in a very natural and clear fashion; in these cases the deferred nodes are stored implicitly in the call stack.

Depth-first search is easily implemented via a stack, including recursively (via the call stack), while breadth-first search is easily implemented via a queue, including corecursively.[2]:45−61

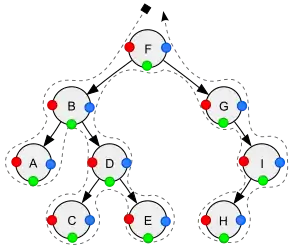

Depth-first search of binary tree

- Pre-order (node access at position red ●): F, B, A, D, C, E, G, I, H;

- In-order (node access at position green ●): A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I;

- Post-order (node access at position blue ●): A, C, E, D, B, H, I, G, F.

These searches are referred to as depth-first search (DFS), since the search tree is deepened as much as possible on each child before going to the next sibling. For a binary tree, they are defined as access operations at each node, starting with the current node, whose algorithm is as follows:[3][4]

The general recursive pattern for traversing a binary tree is this:

- Go down one level to the recursive argument N. If N exists (is non-empty) execute the following three operations in a certain order:[5]

- L: Recursively traverse N's left subtree.

- R: Recursively traverse N's right subtree.

- N: Access (visit) the current node N itself.

- Return by going up one level and arriving at the parent node of N.

There are three methods (patterns) at which position of the parcours (traversal) relative to the node (in the figure: red, green, or blue) the visit (access) of the node shall take place. The choice of exactly one color determines exactly one visit of a node as described below. Access at all three colors results in a threefold visit of the same node yielding the “all-order” sequentialisation:

- F-B-A-A-A-B-D-C-C-C-D-E-E-E-D-B-F-G-G- I-H-H-H- I- I-G-F

Pre-order, NLR

- Access the data part of the current node (in the figure: position red).

- Traverse the left subtree by recursively calling the pre-order function.

- Traverse the right subtree by recursively calling the pre-order function.

The pre-order traversal is a topologically sorted one, because a parent node is processed before any of its child nodes is done.

In-order, LNR

- Traverse the left subtree by recursively calling the in-order function.

- Access the data part of the current node (in the figure: position green).

- Traverse the right subtree by recursively calling the in-order function.

In a binary search tree ordered such that in each node the key is greater than all keys in its left subtree and less than all keys in its right subtree, in-order traversal retrieves the keys in ascending sorted order.[6]

Reverse in-order, RNL

- Traverse the right subtree by recursively calling the reverse in-order function.

- Access the data part of the current node.

- Traverse the left subtree by recursively calling the reverse in-order function.

In a binary search tree, reverse in-order traversal retrieves the keys in descending sorted order.

Post-order, LRN

- Traverse the left subtree by recursively calling the post-order function.

- Traverse the right subtree by recursively calling the post-order function.

- Access the data part of the current node (in the figure: position blue).

The trace of a traversal is called a sequentialisation of the tree. The traversal trace is a list of each visited node. No one sequentialisation according to pre-, in- or post-order describes the underlying tree uniquely. Given a tree with distinct elements, either pre-order or post-order paired with in-order is sufficient to describe the tree uniquely. However, pre-order with post-order leaves some ambiguity in the tree structure.[7]

Generic tree

To traverse any tree with depth-first search, perform the following operations at each node:

- If node not present return.

- Access (= visit) node (pre-order position).

- For each i from 1 to number_of_children − 1 do:

- Recursively traverse i-th child.

- Access node (in-order position).

- Recursively traverse last child.

- Access node (post-order position).

Depending on the problem at hand, the pre-order, post-order, and especially one of the (number_of_children − 1) in-order operations may be void, or access only to a specific child is wanted, so these operations are optional. Also, in practice more than one of pre-order, in-order and post-order operations may be required. For example, when inserting into a ternary tree, a pre-order operation is performed by comparing items. A post-order operation may be needed afterwards to re-balance the tree.

Breadth-first search, or level order

Trees can also be traversed in level-order, where we visit every node on a level before going to a lower level. This search is referred to as breadth-first search (BFS), as the search tree is broadened as much as possible on each depth before going to the next depth.

Other types

There are also tree traversal algorithms that classify as neither depth-first search nor breadth-first search. One such algorithm is Monte Carlo tree search, which concentrates on analyzing the most promising moves, basing the expansion of the search tree on random sampling of the search space.

Applications

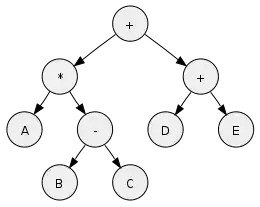

Pre-order traversal can be used to make a prefix expression (Polish notation) from expression trees: traverse the expression tree pre-orderly. For example, traversing the depicted arithmetic expression in pre-order yields "+ * A − B C + D E".

Post-order traversal can generate a postfix representation (Reverse Polish notation) of a binary tree. Traversing the depicted arithmetic expression in post-order yields "A B C − * D E + +"; the latter can easily be transformed into machine code to evaluate the expression by a stack machine.

In-order traversal is very commonly used on binary search trees because it returns values from the underlying set in order, according to the comparator that set up the binary search tree.

Post-order traversal while deleting or freeing nodes and values can delete or free an entire binary tree. Thereby the node is freed after freeing its children.

Also the duplication of a binary tree yields a post-order sequence of actions, because the pointer copy to the copy of a node is assigned to the corresponding child field N.child within the copy of the parent N immediately after returncopy in the recursive procedure. This means that the parent cannot be finished before all children are finished.

Implementations

Pre-order

preorder(node)

if (node == null)

return

visit(node)

preorder(node.left)

preorder(node.right) |

iterativePreorder(node)

if (node == null)

return

s ← empty stack

s.push(node)

while (not s.isEmpty())

node ← s.pop()

visit(node)

//right child is pushed first so that left is processed first

if node.right ≠ null

s.push(node.right)

if node.left ≠ null

s.push(node.left) |

In-order

inorder(node)

if (node == null)

return

inorder(node.left)

visit(node)

inorder(node.right) |

iterativeInorder(node)

s ← empty stack

while (not s.isEmpty() or node ≠ null)

if (node ≠ null)

s.push(node)

node ← node.left

else

node ← s.pop()

visit(node)

node ← node.right |

Post-order

postorder(node)

if (node == null)

return

postorder(node.left)

postorder(node.right)

visit(node) |

iterativePostorder(node)

s ← empty stack

lastNodeVisited ← null

while (not s.isEmpty() or node ≠ null)

if (node ≠ null)

s.push(node)

node ← node.left

else

peekNode ← s.peek()

// if right child exists and traversing node

// from left child, then move right

if (peekNode.right ≠ null and lastNodeVisited ≠ peekNode.right)

node ← peekNode.right

else

visit(peekNode)

lastNodeVisited ← s.pop() |

All the above implementations require stack space proportional to the height of the tree which is a call stack for the recursive and a parent stack for the iterative ones. In a poorly balanced tree, this can be considerable. With the iterative implementations we can remove the stack requirement by maintaining parent pointers in each node, or by threading the tree (next section).

Morris in-order traversal using threading

A binary tree is threaded by making every left child pointer (that would otherwise be null) point to the in-order predecessor of the node (if it exists) and every right child pointer (that would otherwise be null) point to the in-order successor of the node (if it exists).

Advantages:

- Avoids recursion, which uses a call stack and consumes memory and time.

- The node keeps a record of its parent.

Disadvantages:

- The tree is more complex.

- We can make only one traversal at a time.

- It is more prone to errors when both the children are not present and both values of nodes point to their ancestors.

Morris traversal is an implementation of in-order traversal that uses threading:[8]

- Create links to the in-order successor.

- Print the data using these links.

- Revert the changes to restore original tree.

Breadth-first search

Also, listed below is pseudocode for a simple queue based level-order traversal, and will require space proportional to the maximum number of nodes at a given depth. This can be as much as the total number of nodes / 2. A more space-efficient approach for this type of traversal can be implemented using an iterative deepening depth-first search.

levelorder(root)

q ← empty queue

q.enqueue(root)

while not q.isEmpty() do

node ← q.dequeue()

visit(node)

if node.left ≠ null then

q.enqueue(node.left)

if node.right ≠ null then

q.enqueue(node.right)

Infinite trees

While traversal is usually done for trees with a finite number of nodes (and hence finite depth and finite branching factor) it can also be done for infinite trees. This is of particular interest in functional programming (particularly with lazy evaluation), as infinite data structures can often be easily defined and worked with, though they are not (strictly) evaluated, as this would take infinite time. Some finite trees are too large to represent explicitly, such as the game tree for chess or go, and so it is useful to analyze them as if they were infinite.

A basic requirement for traversal is to visit every node eventually. For infinite trees, simple algorithms often fail this. For example, given a binary tree of infinite depth, a depth-first search will go down one side (by convention the left side) of the tree, never visiting the rest, and indeed an in-order or post-order traversal will never visit any nodes, as it has not reached a leaf (and in fact never will). By contrast, a breadth-first (level-order) traversal will traverse a binary tree of infinite depth without problem, and indeed will traverse any tree with bounded branching factor.

On the other hand, given a tree of depth 2, where the root has infinitely many children, and each of these children has two children, a depth-first search will visit all nodes, as once it exhausts the grandchildren (children of children of one node), it will move on to the next (assuming it is not post-order, in which case it never reaches the root). By contrast, a breadth-first search will never reach the grandchildren, as it seeks to exhaust the children first.

A more sophisticated analysis of running time can be given via infinite ordinal numbers; for example, the breadth-first search of the depth 2 tree above will take ω·2 steps: ω for the first level, and then another ω for the second level.

Thus, simple depth-first or breadth-first searches do not traverse every infinite tree, and are not efficient on very large trees. However, hybrid methods can traverse any (countably) infinite tree, essentially via a diagonal argument ("diagonal"—a combination of vertical and horizontal—corresponds to a combination of depth and breadth).

Concretely, given the infinitely branching tree of infinite depth, label the root (), the children of the root (1), (2), …, the grandchildren (1, 1), (1, 2), …, (2, 1), (2, 2), …, and so on. The nodes are thus in a one-to-one correspondence with finite (possibly empty) sequences of positive numbers, which are countable and can be placed in order first by sum of entries, and then by lexicographic order within a given sum (only finitely many sequences sum to a given value, so all entries are reached—formally there are a finite number of compositions of a given natural number, specifically 2n−1 compositions of n ≥ 1), which gives a traversal. Explicitly:

- ()

- (1)

- (1, 1) (2)

- (1, 1, 1) (1, 2) (2, 1) (3)

- (1, 1, 1, 1) (1, 1, 2) (1, 2, 1) (1, 3) (2, 1, 1) (2, 2) (3, 1) (4)

etc.

This can be interpreted as mapping the infinite depth binary tree onto this tree and then applying breadth-first search: replace the "down" edges connecting a parent node to its second and later children with "right" edges from the first child to the second child, from the second child to the third child, etc. Thus at each step one can either go down (append a (, 1) to the end) or go right (add one to the last number) (except the root, which is extra and can only go down), which shows the correspondence between the infinite binary tree and the above numbering; the sum of the entries (minus one) corresponds to the distance from the root, which agrees with the 2n−1 nodes at depth n − 1 in the infinite binary tree (2 corresponds to binary).

References

- "Lecture 8, Tree Traversal". Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- Pfaff, Ben (2004). An Introduction to Binary Search Trees and Balanced Trees. Free Software Foundation, Inc.

- Binary Tree Traversal Methods

- "Preorder Traversal Algorithm". Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- L before R means the (standard) counter-clockwise traversal — as in the figure.

The execution of N before, between, or after L,R determines one of the described methods.

If the parcours is taken the other way around (clockwise), then the traversal is called reversed. This is described in particular for reverse in-order, when the data are to be retrieved in descending order. - Wittman, Todd. "Tree Traversal" (PDF). UCLA Math. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 13, 2015. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- "Algorithms, Which combinations of pre-, post- and in-order sequentialisation are unique?, Computer Science Stack Exchange". Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- Morris, Joseph M. (1979). "Traversing binary trees simply and cheaply". Information Processing Letters. 9 (5). doi:10.1016/0020-0190(79)90068-1.

- General

- Dale, Nell. Lilly, Susan D. "Pascal Plus Data Structures". D. C. Heath and Company. Lexington, MA. 1995. Fourth Edition.

- Drozdek, Adam. "Data Structures and Algorithms in C++". Brook/Cole. Pacific Grove, CA. 2001. Second edition.

- http://www.math.northwestern.edu/~mlerma/courses/cs310-05s/notes/dm-treetran

External links

- Storing Hierarchical Data in a Database with traversal examples in PHP

- Managing Hierarchical Data in MySQL

- Working with Graphs in MySQL

- Sample code for recursive and iterative tree traversal implemented in C.

- Sample code for recursive tree traversal in C#.

- See tree traversal implemented in various programming language on Rosetta Code

- Tree traversal without recursion