Traditional Chinese marriage

Traditional Chinese marriage (Chinese: 婚姻; pinyin: hūnyīn) is a ceremonial ritual within Chinese societies that involves not only a union between spouses, but also a union between the two families of a man and a woman, sometimes established by pre-arrangement between families. Marriage and family are inextricably linked, which involves the interests of both families. Within Chinese culture, romantic love and monogamy was the norm for most citizens. Around the end of primitive society, traditional Chinese marriage rituals were formed, with deer skin betrothal in the Fuxi era, the appearance of the "meeting hall" during the Xia and Shang dynasties, and then in the Zhou dynasty, a complete set of marriage etiquette ("six rituals") gradually formed. The richness of this series of rituals proves the importance the ancients attached to marriage. In addition to the unique nature of the "three letters and six rituals", monogamy, remarriage and divorce in traditional Chinese marriage culture are also distinctive.

Etymology

In more ancient writings for the word 婚姻, the former has the radical 昏 (pinyin: hūn, literally "dusk, nightfall, twilight, dark") beside the radical 女 (pinyin: nǚ, literally "a female"). This implies that the wedding ceremony is typically performed in the evening, which is deemed as a time of fortune. Similarly, 姻 (pinyin: yīn) has the same pronunciation as 因 (pinyin: yīn). According to Zhang Yi's (張揖) Guangya Shigu (廣雅•釋詁), a dictionary of ancient Chinese characters, 因 (pinyin: yīn) means "friendliness", "love" and "harmony", indicating the correct way of living for a married couple.

Marriage in a Confucian context

In Confucian thought, marriage is of grave significance to both families and society, as well as being important for the cultivation of virtue. Traditionally incest has been defined as marriage between people with the same surname. "One of the earliest marriage prohibitions, and one surviving to this day, was that forbidding persons of the same surname to marry. An imperial decree of 484 A.D. states that this rule was promulgated far back in the Chou dynasty, which was from I122 to 255 B.C.' Any one marrying within his clan received sixty blows, and the marriage was declared null and void. It was feared that such mating would produce weak offspring.”[1] From the perspective of a Confucian family, marriage brings together families of different surnames and continues the family line of the paternal clan. This is generally why giving birth to a boy is preferred over a girl. Therefore, the benefits and demerits of any marriage are important to the entire family, not just the individual couples. Socially, the married couple is thought to be the basic unit of society. In Chinese history there have been many times when marriages have affected the country's political stability and international relations. For International Relations,“intermarriage has continued throughout Chinese history as a means of establishing and maintaining relations among families in the private sphere, as well as a factor in political careers. " For example, "Marriage alliances, or ho-ch'in 和亲,literally 'harmonious kinship,' was something new in itss Han-era application. It was a part of a formal peace treaty arrangement at the interstate level, designed to pacify the powerful Hsiung-nu 匈奴 empire" During the Han Dynasty, the rulers of the powerful Xiongnu tribe demanded women from the imperial family. Many periods of Chinese history were dominated by the families of the wife or mother of the ruling emperor. For country's political stability, during the Qing dynasty, although no "evidence of prohibitions against ethnic intermarriage within the Eight Banners ",[2] "in elite families of the ruling class, primary wives were almost entirely Manchu, while qie (commonly translated as ‘concubines’) and other partners of lower status could be Han".[2] In the Qing Dynasty, most of the high officials were mainly Manchu, so in order to protect the interests of the family, in the selection of a wife will be very important whether the woman was born in the "eight banners". For example,"the ethnicity apparent in the maiden names of wives in genealogies from elite Manchu descent groups, such as the Imperial Lineage."[2]

Ancient Chinese marriages

Marriages in early societies

In modern Chinese thinking, people in "primitive" societies did not marry, but had sexual relationships with one another indiscriminately. Such people were thought to live like animals, and they did not have the precise concept of motherhood, fatherhood, sibling, husband and wife, and gender, not to mention match-making and marriage ceremony. Part of the Confucian "civilizing mission" was to define what it meant to be a Father or a Husband, and to teach people to respect the proper relationship between family members and regulate sexual behavior.

Mythological origin

The story about the marriage of sister and brother Nüwa and Fu Xi told how they invented proper marriage procedures after marrying. At that time the world was unpopulated, so the siblings wanted to get married but, at the same time, they felt ashamed. So they went up to Kunlun Mountains and prayed to the heavens. They asked for permission for their marriage and said, "if you allow us to marry, please make the mist surround us." The heavens gave permission to the couple, and promptly the peak was covered in mist. It is said that in order to hide her shyness, Nüwa covered her blushing face with a fan. Nowadays in some villages in China, the brides still follow the custom and use a fan to shield their faces.

Historic marriage practices

Endogamy among different classes in China were practiced, the upper class like the Shi class married among themselves, while commoners married among themselves also, avoiding marriage with slaves and other ordinary people. This practice was enforced under the law.[3]

Maternal marriage and monogamy

In a maternal marriage, a male would become a son-in-law who lived in the wife's home. This happened in the transformation of antithetic marriage into monogamy, which signified the decline of matriarchy and the growing dominance of patriarchy in ancient China.

Marriage matters in Xinjiang (1880–1949)

Even though Muslim women are forbidden to marry non-Muslims in Islamic law, from 1880–1949 it was frequently violated in Xinjiang since Chinese men married Muslim Turki (Uyghur) women, a reason suggested by foreigners that it was due to the women being poor, while the Turki women who married Chinese were labelled as whores by the Turki community, these marriages were illegitimate according to Islamic law but the women obtained benefits from marrying Chinese men since the Chinese defended them from Islamic authorities so the women were not subjected to the tax on prostitution and were able to save their income for themselves.

Chinese men gave their Turki wives privileges which Turki men's wives did not have, since the wives of Chinese did not have to wear a veil and a Chinese man in Kashgar once beat a mullah who tried to force his Turki Kashgari wife to veil. The Turki women also benefited in that they were not subjected to any legal binding to their Chinese husbands so they could make their Chinese husbands provide them with as much their money as she wanted for her relatives and herself since otherwise the women could just leave, and the property of Chinese men was left to their Turki wives after they died.[4]

Turki women considered Turki men to be inferior husbands to Chinese and Hindus. Because they were viewed as "impure", Islamic cemeteries banned the Turki wives of Chinese men from being buried within them, the Turki women got around this problem by giving shrines donations and buying a grave in other towns. Besides Chinese men, other men such as Hindus, Armenians, Jews, Russians, and Badakhshanis intermarried with local Turki women.[5]

The local society accepted the Turki women and Chinese men's mixed offspring as their own people despite the marriages being in violation of Islamic law. Turki women also conducted temporary marriages with Chinese men such as Chinese soldiers temporarily stationed around them as soldiers for tours of duty, after which the Chinese men returned to their own cities, with the Chinese men selling their mixed daughters with the Turki women to his comrades, taking their sons with them if they could afford it but leaving them if they couldn't, and selling their temporary Turki wife to a comrade or leaving her behind.[6]

Marriage during the Han Dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE)

Marriages during this time included a number of mandatory steps, of which the most important of them was the presentation of betrothal gifts from the groom and his family to the bride and her family. The bride's family then countered with a dowry. Sometimes the bride's family would buy goods with the betrothal money. Using a betrothal gift for family financial needs rather than saving it for the bride was viewed as dishonorable because it appeared as though the bride has been sold. A marriage without a dowry or a betrothal gifts was also seen as dishonorable. The bride was seen as a concubine instead of a wife. Once all the goods were exchanged the bride was taken to the ancestral home of the groom. There she was expected to obey her husband and his living relatives. Women continued to belong to their husband's families even if they had passed. If the widow's birth family wanted her to marry again, they would often have to ransom her back from her deceased husband's family. If they had any children they stayed with his family.[7]

Marriage brokers during the Ming Dynasty

In the Ming period, marriage was considered solemn and according to the law written in The Ming Code (Da Ming Lü), all commoners' marriages must follow the rules written in Duke Wen's Family Rules (Wen Gong Jia Li).[8] The rules stated that "in order to arrange a marriage, an agent must come and deliver messages between the two families."[9] A marriage broker had the license to play important roles by arranging marriages between two families. Sometimes both families were influential and wealthy and the matchmaker bonded the two families into powerful households. Studies have shown that, "In the Ming and Qing dynasties, a number of noble families emerged in Jiaxing of Zhejiang, where marriage is the most important way to expand their clan strength."[10] Hence, marriage brokers were crucial during the Ming era, which offered us an insight of the lives of the Ming commoners.

Instead of using the more gender general term "mei ren" (媒人), texts more frequently referred to marriage brokers as "mei po" (媒婆). Since "Po" (婆) translates to "grannies" in English, it suggests that elderly female characters dominated the "marriage market". Indeed, in the novel The Golden Lotus (Jing Ping Mei), the four matchmakers Wang, Xue, Wen, Feng were all elderly female characters.[11] In ancient China, people believed that marriages belong to the "Yin" side (the opposite is "Yang"), which corresponds to females. In order to maintain the balance between Yin and Yang, women should not interfere with the Yang side and men should not interfere with the Yin side. Since breaking the balance may lead to disorder and misfortune,[12] men were rarely seen in marriage arrangements. Furthermore, unmarried girls were not in the occupation because they themselves knew little about marriage and were not credible in arranging marriages. As a result, almost all marriage brokers in the literary work were presented as elderly females.

Being a successful marriage broker required various special skills. Firstly, the broker must be very persuasive. The broker must persuade both sides of the marriage that the arrangement was impeccable, even though many times the arrangement was actually not perfect. In Feng Menglong's "Old Man Zhang Grows Melons and Marries Wennü" in the collection Stories Old and New (Gu Jin Xiao Shuo), he wrote about an eighty-year-old man who married an eighteen-year young girl.[13] The marriage was arranged by two matchmakers, Zhang and Li. Given the age difference, the marriage seemed impossible, but the two brokers still managed to persuade the father of the girl to marry her to the old man. Feng Menglong described them as "Once they start to speak the match is successfully arranged, and when they open their mouths they only spoke about harmony."[13] The brokers gave powerful persuasions by avoiding about mentioning the differences between the couples they arranged. Which, only speak about the positive side. In addition to persuasion techniques, the brokers must possess great social skills. They needed to know a network of people so that when the time comes for marriage, they were able to seek the services of the brokers. Finally, when someone came to the broker, she must be able to pick out a matching suitors according to her knowledge of the local residents. Normally a perfect couple must have similar social status, economic status, and age. Wealthy families would look for a bride of similar social status who could manage the family finances and, most importantly, produce sons to inherit the family's wealth. Poor families, on the other hand, will not be as demanding and will only look for a bride who is willing to work hard in the fields. Sometimes they even need to travel to neighboring towns for a match, hence the verse "Traveling to the east household, traveling to the west household, their feet are always busy and their voices are always loud."[13] Furthermore, mediators are required to know some mathematics and simple characters in order to write the matrimonial contract. The contract included "the sum of the bride price, the identity and age of both partners, and the identity of the person who presided over the wedding ceremony, usually the parents or grandparents."[14] Without the knowledge of math and simple written characters, composing such a detailed contract would be impossible.

The matchmakers made a living not only by facilitating successful marriage arrangements, but also by delivering messages between the two families. When they visited the households to deliver messages, the hosts usually provided them food and drinks to enjoy, hence the verse "Asking for a cup of tea, asking for a cup of alcohol, their faces are 3.3 inches thick (they are really cheeky)."[13] However, these "visiting payments" were tiny compared to the payment they receive for a successful marriage. The visiting payment was always measured by "wen" or cash. Whereas, the final payment was measured by "liang" or taels, and one wen was equivalent to a thousand taels. Therefore, the brokers would spend most of their time travelling back and forth between the two households to persuade them of the marriage. In addition, the matchmakers receive payments for introducing young girls to wealthy men. In Zhang Dai's diary The Dream Collection of Taoan (Taoan Meng Yi), he described a scene in which matchmakers brought young beautiful girls to the houses of wealthy customers to choose. Even if the customer was not satisfied he would reward the matchmaker several hundreds wen.[15]

As marriage brokers, these grannies also possessed the "guilty knowledge" of secret affairs. In The Golden Lotus (Jing Ping Mei),[11] the matchmaker Wang speculated that Ximen Qing was fond of the married woman Pan Jinlian, so she introduced Pan to Ximen, helped them to have an affair and hide the secret for them.[16] According to the law married woman must be loyal to her husband, and anyone who discovered an affair of the woman should report her immediately. Although, the matchmakers were licensed to keep secrets about affairs because keeping privacy of their clients was their obligation. Even so, they were usually criticized for doing so. In The Golden Lotus Wang was blamed for egging ladies on having improper affairs.

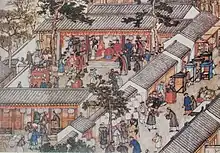

Traditional marriage rituals

Chinese marriage became a custom between 402 and 221 BC. Despite China's long history and many different geographical areas, there are essentially six rituals, generally known as the three letters and six etiquettes (三書六禮). Unfortunately for some traditional families, the wife's mother cannot go to her son-in-law's family until one year (according to the Chinese lunar calendar or Chinese Lunar New Year) after the wedding has elapsed. However, during this one year the daughter can go back at any time.

Six etiquettes

The wedding ceremony consisted of six basic procedures: making a proposal of marriage (nacai), requesting the bride’s name and date of birth(wenming), sending news of divination results and betrothal gifts (naji), sending wedding presents to the bride’s house (nazheng), requesting the date of the wedding (qingqi), and fetching in the bride in person (qinying). The details of each ritual could vary.[17]

- Proposal: After an unmarried boy's parents found a potential daughter-in-law, they located a matchmaker whose job was to assuage the conflict of interests and general embarrassments when discussing the possibility of marriage on the part of two families largely unknown to each other. Marriages were chosen based upon the needs of reproduction and honor, as well as the need of the father and husband.

- Birthdates: If the selected girl and her parents did not object to the proposal, the matchmaker would match the birthdates (Chinese: 秊庚八字; pinyin: niángēng bāzì; lit. 'the 8 cyclic characters for year, month, day and hour of birth of a man, which determine his fate') in which suan ming (Chinese fortune telling) is used to predict the future of that couple-to-be. If the result of suan ming was good, they then would go to the next step, submitting bride price.

- Bridewealth (betrothal gifts): At this point the bridegroom's family arranged for the matchmaker to present a bride price (betrothal gifts), including the betrothal letter, to the bride's family.

- Wedding gifts: The groom's family would then send an elaborate array of food, cakes, and religious items to the bride's family.

- Arranging the wedding: Before the wedding ceremony, two families would arrange a wedding day according to Chinese tung shing. Selecting an auspicious day to assure a good future for the couple is as important as avoiding what is believed to be an unlucky day. In some cases there may be no auspicious dates and the couple will have to review their potential date range.

- Wedding ceremony: The final ritual would be the actual wedding ceremony where bride and groom become a married couple, which consists of many elaborate parts (see below):

- Wedding procession: Before the meeting party's arrival, the bride would be helped by a respectable old woman to tie up her hair with colorful cotton threads. She would wear a red skirt because the Chinese believed red symbolised happiness. When the party arrived, the bride must cry with her mother to symbolize her reluctance to leave home. She would then be led or carried by her elder brother to the sedan. From here, the wedding procession from the bride's home to the groom's home consists of a traditional band, the bride's sedan, the maids of honor's sedans (if there are maids of honor), and bride's dowry in the forms other than money. The most common dowries included scissors like two butterflies never separating, rulers indicating acres of fields, and vases for peace and wealth.

- Welcoming the bride: The wedding procession of the bride's family stops at the door of the groom's home. In the meeting party the groom would meet a series of difficulties intentionally set in his path. Only after coping with these could he pass to see his wife-to-be.

- Actual wedding ceremonies: On the arrival of the sedan at the wedding place, there would be music and firecrackers. The bride would be led along the red carpet in a festive atmosphere. The groom, also in a red gown, would kowtow three times to worship the heaven, parents and spouse. Equivalent to exchanging vows in the west, the couple would pay respect to the Jade Emperor, the patron family deities (or patron buddhas and bodhisattvas), paying respect to deceased ancestors, the bride and groom's parents and other elders, and paying respect to each other. Then, the new couple would go to their bridal chamber and guests would be treated to a feast.

traditional Chinese wedding dresses

traditional Chinese wedding dresses - Wedding banquets In Chinese society, the wedding banquet is known as xǐ-jǐu (喜酒, lit. joyful wine), and is sometimes far more important than the actual wedding itself. There are ceremonies such as the bride presenting wines or tea to parents, spouse, and guests. In modern weddings, the bride generally picks red (following Chinese tradition) or white (more Western) for the wedding, but most will wear the red traditional garment for their formal wedding banquet. Traditionally, the groom is not responsible for the cost of the wedding invitation sweet treats (often pastries), the banquet invitations, and the wedding itself. Wedding banquets are elaborate and consist usually of 5–10 courses, with ingredients such as shark fin, abalone, lobster, squab, sea cucumber, swift nests or fish roe in soup or as decoration on top of a dish to symbolize fertility, and local delicacies. Traditionally, the father of the bride is responsible for the wedding banquet hosted on the bride's side and the alcohol consumed during both banquets. The wedding banquets are two separate banquets: the primary banquet is hosted once at the bride's side, the second banquet (smaller banquet) at the groom's side. While the wedding itself is often based on the couple's choices, the wedding banquets are a gesture of thanks and appreciation, to those that have raised the bride and groom (such as grandparents and uncles). It is also to ensure the relatives on each side meet the relatives on the other side. Thus out of respect for the elders, wedding banquets are usually done formally and traditionally, which the older generation is thought to be more comfortable with. On the night of the wedding day, there was a custom in some places for relatives or friends to banter the newlyweds. Though this seemed a little noisy, both of them dropped shyness and got familiar with each other. On the third day of the marriage, the new couple would go back to the bride's parents' home. They would be received with also a dinner party including relatives.

Modern practices

Since the late 1990s, it has become popular to create an elaborate wedding album, often taken at a photography studio.[18] The album usually consists of many pictures of the bride and groom taken at various locations with many different outfits. In Singapore, these outfits often include wedding outfits belonging to different cultures, including Arab and Japanese wedding outfits. In contrast to Western wedding pictures, the Chinese wedding album will not contain pictures of the actual ceremony and wedding itself.

In Mandarin Chinese, a mang nian "盲年“, or 'blind year', when there are no first days of spring, such as in year 2010, a Year of the Tiger, is considered an ominous time to marry or start a business.[19] In the preceding year, there were two first days of spring.

In recent years, Confucian wedding rituals have become popular among Chinese couples. In such ceremonies, which are a recent innovation with no historic antecedent, the bride and groom bow and pay respects to a large portrait of Confucius hanging in the banquet hall while wedding attendants and the couple themselves are dressed in traditional Chinese robes.[20]

Before the bride and groom enter the nuptial chambers, they exchange nuptial cups and perform ceremonial bows as follows:[21]

- first bow – Heaven and Earth

- second bow – ancestors

- third bow – parents

- fourth bow – spouse

Traditional divorce process

In traditional Chinese society, there are three major ways to dissolve a marriage.

The first one is no-fault divorce. According to the Tang Code, the legal code of the Tang Dynasty (618–907), a marriage may be dissolved due to personal incompatibility, provided that the husband writes a divorce note.

The second way (義绝) is through state-mandated annulment of marriage. This applies when one spouse commits a serious crime (variously defined, usually more broadly for the wife) against the other or his/her clan. If the couple does not take the initiative to divorce when arose the situation of (義绝), the state will intervene to force them to divorce. If one side refused to divorce, the law must investigate the criminal liability of the party with a one-year prison sentence. Once a divorce is adjudged, they must not be reunited.[22]

The third way of Chinese divorce process is mutual divorce (和離). It is a way that both husband and wife can have the power to divorce. However, It requires both of their agreement. In Chinese Marriage, this way of divorce is to ensure both husband and wife have the equal power to protect themselves, such as their property. It also enhanced the concept of responsibility in Chinese marriage. Divorce is a responsibility to each other. So, the country or the government won't intervene the divorce most of the time.[23]

Finally, the husband may unilaterally declare a divorce. To be legally recognized, it must be based on one of the following seven reasons (七出):

- The wife lacks filial piety towards her parents-in-law (不順舅姑). This makes the parents-in-law potentially capable of breaking a marriage against both partners' wills.

- She fails to bear a son (無子).

- She is vulgar or lewd/adulterous (淫).

- She is jealous (妒). This includes objecting to her husband taking an additional wife or concubine.

- She has a vile disease (有惡疾).

- She is gossipy (口多言).

- She commits theft (竊盜).

There are, however, three clearly defined exceptions (三不去), under which unilateral divorce is forbidden despite the presence of any of the seven aforementioned grounds:

- She has no family to return to (有所取無所歸).

- She had observed a full, three-year mourning for a parent-in-law (與更三年喪).

- Her husband was poor when they married, and is now rich (前貧賤後富貴).

The above law about unilateral divorce was in force from Tang Dynasty up to its final abolition in the Republic of China's Civil Code (Part IV) Section 5, passed in 1930.[24]

Divorce in contemporary China

After the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949, the country's new Marriage Law also explicitly provided for lawful divorces. Women were permitted to divorce their husbands and many did, sparking resistance from rural males especially. Kay Ann Johnson reported that tens of thousands of women in north central China were killed for seeking divorces or committed suicide when blocked from doing so.[25]

During the Mao era (1949–1976) divorce was rare, but in the reform era, it has become easier and more commonplace. A USC U.S.-China Institute article reports that the divorce rate in 2006 was about 1.4/1000 people, about twice what it was in 1990 and more than three times what it was in 1982. Still, the divorce rate in China is less than half what it is in the United States.[26] One of the most important breakthroughs in the marriage institution were amendments added to the Marriage Law in 2001, which shortened the divorce-application procedure and added legitimate reasons for divorce, such as emphasizing the importance of faithfulness within a married couple, a response to rising failure of marriages due to unfaithful affairs during marriage that have come into public knowledge.[27] With the rising divorce rates nowadays, public discussions and governmental organs often criticize the lack of effort in marriage maintenance which many couples express. This is evident, for example in the new 'divorce buffer zones' established in the marriage registration offices in certain provinces, which is a room where the couples wait, as a stage within the divorce application procedure, and are encouraged to talk things over and consider giving their marriage another chance.[28] However, such phenomena don't contradict the increasing permissiveness of the systems and of married couples which lead to the constant growth in divorce rates in China.

Amendments have also been made to Article 32 of the revised 2001 Marriage Law. Parties to a marriage can apply for Divorce under, and by showing, the following grounds:

- Bigamy or a married person cohabiting with a third party;

- Domestic violence or maltreatment and desertion of one family member by another;

- Bad habits of gambling or drug addiction that remain incorrigible despite repeated admonition;

- Separation caused by incompatibility, which lasts two full years;

- Any other circumstances causing alienation of mutual affection.

Monogamy

In ancient China, women's social status was not as good as men. A woman could only obey and rely on her husband. She shared her husband’s class, whether he was a peasant, merchant, or official; accordingly, the clothes she could wear and the etiquette. she was expected to display depended on her husband’s background and achievements.[17] If her husband was dead, she could remarry but would be seen as not decent. The neo-Confucian opposition to widow remarriage was expressed in an oft-quoted aphorism of Zhu Xi: "It is a small matter to starve to death, but a large matter to lose one's virtue."[29] Moreover, the government has also issued measures against widow remarriage. For example,"The state reinforced the neo-Confucian attitude against widow remarriage by erecting commemorative arches to honour women who refused to remarry. In 1304, the Yuan government issued a proclama-tion declaring that all women widowed before they were thirty who remained chaste widows until they were fifty were to be so honoured. The Ming and Qing continued the practice." [29]

The virtues of chaste widowhood were extolled by instructions for women, such as the Nu Lun Yu (Analects for Women).[29] While a man could have though only one wife but many concubines and marry someone else as new wife if the wife passed away before him. The general dignitaries also had only one wife but many concubines.

Sororate marriage

Sororate marriage is a custom in which a man marries his wife's sister(s). Later it is expanded to include her cousins or females from the same clan. The Chinese name is 妹媵 (妹=younger sister, 媵=co-bride/concubinage). It can happen at the same time as he marries the first wife, at a later time while the wife is still alive, or after she dies. This practice occurred frequently among the nobility of the Zhou Dynasty (1045 BC – 256 BC), with cases occurring at later times.

Multiple wives with equal status

- Emperors of some relatively minor dynasties are known to have multiple empresses.

- Created by special circumstances. For example, during wartime a man may be separated from his wife and mistakenly believe that she had died. He remarries, and later the first wife is found to be alive. After they are reunited, both wives may be recognized.

- Qianlong Emperor of Qing dynasty began to allow polygamy for the specific purpose of siring heirs for another branch of the family (see Levirate marriage). Called "multiple inheritance" (兼祧), if a man is the only son of his father 單傳, and his uncle has no son, then with mutual agreement he may marry an additional wife. A male child from this union becomes the uncle's grandson and heir. The process can be repeated for additional uncles.

Beside the traditional desire for male children to carry on the family name, this allowance partially resolves a dilemma created by the emperor himself. He had recently banned all non-patrilineal forms of inheritance, while wanting to preserve the proper order in the Chinese kinship. Therefore, a couple without son cannot adopt one from within the extended family. They either have to adopt from outside (which was regarded by many as passing the family wealth to unrelated "outsiders"), or become heirless. The multiple inheritance marriages provided a way out when the husband's brother has a son.

Ruzhui marriage

The custom of ruzhui (入赘) applied when a relatively wealthy family had no male heirs, while a poorer family had multiple male children. Under these circumstances, a male from the poorer family, generally a younger sibling, will marry into the wealthier family in order to continue their family line. In a ruzhui (lit., 'the [man] becoming superfluous') marriage, the children will take on the surname of the wife.[30]

Concubinage

In ancient China, concubinage was very common, and men who could afford it usually bought concubines and took them into their homes in addition to their wives. The standard Chinese term translated as "concubine" means "concubine: my and your servant. In the family hierarchy, the principal wife (diqi) ranked second only to her husband, while a concubine was always inferior to the wife, even if her relations with the husband were more intimate.[17] Women in concubinage (妾) were treated as inferior, and expected to be subservient to the wife (if there was one).[31] The women were not wedded in a whole formal ceremony, had less right in the relationship, and could be divorced arbitrarily. They generally came from lower social status or were bought as slaves. "She shared her husband’s class, whether he was a peasant, merchant, or official; accordingly, the clothes she could wear and the etiquette. she was expected to display depended on her husband’s background and achievements."[32]

Women who had eloped may have also become concubines since a formal wedding requires her parents' participation.

The number of concubines was sometime regulated, which differs according to the men's rank. In ancient China, men of higher social status often supported several concubines, and Chinese emperors almost always had dozens of, even hundreds of royal concubines.[33]

Polyandry

Polyandry, the practice of one woman having multiple husbands, is traditionally considered by Han as immoral, prohibited by law, and uncommon in practice. However, historically there have been instances in which a man in poverty rents or pawns his wife temporarily. However amongst other Chinese ethnicities polyandry existed and exists, especially in mountainous areas.

In a subsistence economy, when available land could not support more than one family, dividing it between surviving sons would eventually lead to a situation in which none would have the resources to survive; in such a situation a family would together marry a wife, who would be the wife of all the brothers in the family. Polyandry in certain Tibetan autonomous areas in modern China remains legal. This however only applies to the ethnic minority Tibetans of the region and not to other ethnic groups.

See also

Notes

- Baber, Ray Erwin (1934). "Marriage in Ancient China". The Journal of Educational Sociology. 8 (3): 131–140. doi:10.2307/2961796. ISSN 0885-3525.

- Chen, Bijia; Campbell, Cameron; Dong, Hao (2018). "Interethnic marriage in Northeast China, 1866–1913". Demographic Research. 38: 929–966. ISSN 1435-9871.

- Rubie Sharon Watson; Patricia Buckley Ebrey; Joint Committee on Chinese Studies (U.S.) (1991). Marriage and inequality in Chinese society. University of California Press. p. 225. ISBN 0-520-07124-7. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

- Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880–1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2.

- Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880–1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2.

- Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880–1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2.

- 1952–, Wiesner, Merry E. (2011). Gender in history : global perspectives (2nd ed.). Malden, Mass: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405189958. OCLC 504275500.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- 大明律附录大明令. 沈阳: 辽沈书社. 1990.

- 大明集礼·士庶婚礼. 台北: 台湾商务印书馆. 1986.

- Ed, Fei, C.K. (1998). "Chinese Family Rules and Clan Regulations". Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press – via JSTOR.

- 兰陵笑笑生 (2016). 金瓶梅. 新加坡: 新加坡南洋出版社.

- P. Steven, Sangren (1987). "Orthodoxy, Heterodoxy, and the Structure of Value in Chinese Rituals". Modern China. 13 (1): 63–89. doi:10.1177/009770048701300104. S2CID 145645906 – via JSTOR.

- 冯, 梦龙 (1993). 三言-喻世明言. 山东: 齐鲁书社.

- Dominiek, Delporte (2003). "Precedents and the Dissolution of Marriage Agreements in Ming China (1368–1644). Insights from the 'Classified Regulations of the Great Ming,' Book 13". Law and History Review. 21 (2): 271–296. doi:10.2307/3595093. JSTOR 3595093.

- 张, 岱. 陶庵梦忆. pp. 扬州瘦马.

- 李, 军锋 (2011). "民俗学视野下的《金瓶梅》媒妁现象探析". 郧阳师范高等专科学校学报. 2011年04期.

- Sexuality in China: Histories of Power and Pleasure. University of Washington Press. 2018. ISBN 978-0-295-74346-2. JSTOR j.ctvcwnwj4.

- Davis, Edward (2005). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Chinese Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 897–899. ISBN 9780415241298.

- Jennifer 8. Lee, 'The New York Times', Sunday 8 January 2010 p. ST-15 (Sunday Styles)

- Yang, Fenggang; Joseph Tamney (2011). Confucianism and Spiritual Traditions in Modern China and Beyond. BRILL. pp. 325–327. ISBN 9789004212398.

- Li Wenxian (2011). "Worshipping in the Ancestral Hall". Encyclopedia of Taiwan. Taipei: Council for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on 1 May 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- 崔蘭琴 (2008).《中国古代的义绝制度》載《法学研究》2008 年第5期,p.149-160, Retrieved from http://www.faxueyanjiu.com/ch/reader/create_pdf.aspx?file_no=20080512&year_id=2008&quarter_id=5&falg=1

- 易松国, 陈丽云, and 林昭寰. "中国传统离婚政策简析." 深圳大学学报(人文社会科学版) 19.6 (2002): 39–44. Retrieved from http://www.faxueyanjiu.com/ch/reader/create_pdf.aspx?file_no=20080512&year_id=2008&quarter_id=5&falg=1

- law.moj.gov.tw

- Kay Ann Johnson, Women, the Family, and Peasant Revolution in China http://www.press.uchicago.edu/presssite/metadata.epl?mode=toc&bookkey=76671%5B%5D

- "Divorce is increasingly common". USC US-China Institute. Archived from the original on 2014-02-19. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- Romantic Materialism (the development of the marriage institution and related norms in China), Thinking Chinese, October 2011

- 江苏将推广设立离婚缓冲室 (Chinese), sina.com, May 23, 2011

- Waltner, Ann (1981). "Widows and Remarriage in Ming and Early Qing China". Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques. 8 (3): 129–146. ISSN 0315-7997. JSTOR 41298764.

- Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (2016-11-11). "For Chinese Women, a Surname Is Her Name". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- Patrick Fuliang Shan, “Unveiling China’s Relinquished Marital Mode: A Study of Yuan Shikai’s Polygamous Household,” Frontiers of History in China, (Vol. 14, No. 2, July 2019), pp. 185–211;

- Sexuality in China: Histories of Power and Pleasure. University of Washington Press. 2018. ISBN 978-0-295-74346-2.

- "Concubines in Ancient China". Beijing Made Easy.

18. Gender in History, Global Perspectives, Second Edition. Written by Merry E.Wiesner-Hanks.(p29-33)

Further reading

- Guide to China Divorce and Separation

- spousal interests in real properties and corporate equities in China

- Wolf, Arthur P. and Chieh-shan Huang. 1985. Marriage and Adoption in China, 1845–1945. Stanford University Press. This is the most sophisticated anthropological account of Chinese marriage.

- Diamant, Neil J. 2000. Revolutionizing the Family: politics, love and divorce in urban and rural China, 1949–1968. University of California Press.

- Wolf, Margery. 1985. Revolution Postponed: Women in Contemporary China. Stanford University Press.

- Alford, William P., "Have You Eaten, Have You Divorced? Debating the Meaning of Freedom in Marriage in China", in Realms of Freedom in Modern China (William C. Kirby ed., Stanford University Press, 2004).