Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth is an art book and matching exhibition exploring images of artwork, illustrations, maps, letters and manuscripts of J. R. R. Tolkien, curated by the Bodleian Library and written by Catherine McIlwaine, Tolkien archivist at the Bodleian. The book documents Tolkien's creative processes behind works like The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion. The book, with some 300 illustrations, mainly in double-page spreads of image and accompanying text, draws on the collection at the Bodleian Library, Marquette University, and private collections.[1] The book and exhibition have been widely admired by commentators.

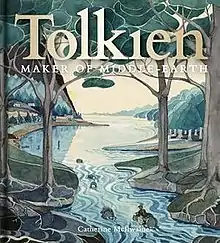

Cover of first edition, showing Tolkien's painting "Bilbo Comes to the Huts of the Raft-Elves" | |

| Author | Catherine McIlwaine |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Tolkien's legendarium |

| Genre | Art |

| Published | 1 June 2018 |

| Publisher | The Bodleian Library |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 288 |

| ISBN | 978-1851244850 |

The book's appearance was timed to coincide with an exhibition the same name at the Bodleian Library which ran from 1 June 2018 (publication date of the book) to 28 October 2018. It presented some 200 images of Tolkien's life and work.[2][3]

Book

Contents

The book is divided into two parts. The first part is a series of essays on key aspects of Tolkien's Middle-earth oeuvre. There is a brief biography of Tolkien by Catherine McIlwaine, and a chapter by John Garth on how the Inklings, a group that included C. S. Lewis, influenced Tolkien. Verlyn Flieger describes Tolkien's concept of faerie, referencing works such as On Fairy-Stories and Smith of Wootton Major as well as his Middle-earth books. Carl F. Hostetter introduces Tolkien's invented Elvish languages, Quenya and Sindarin. Tom Shippey comments on Tolkien's creative use of Norse mythology, and the northern ethos of courage without hope of victory, citing Beowulf and the Poetic Edda's Lay of Fafnir, to suit his own taste, faith, and knowledge of philology. Finally, Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull introduce Tolkien's visual art, showing that his artwork was as thorough as his writing.[4]

The second part is a catalogue of the exhibition, covering Tolkien's letters, childhood, student days, inventiveness, his long effort on The Silmarillion myths, his work at home, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and his maps of Middle-earth.[4]

Illustrations

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth has some 300 colour illustrations.[5] Many illustrations occupy a full page, usually with a description facing it to form a double-page spread on a single item. Each image or group of similar images has an exhibition-like title and summary, stating the image's date, materials used, size, exhibition date and number, appearances in published literature (whether by Tolkien or others), and the manuscript number. There follows a description of the image in text.[4]

Publication history

The book was published in a large format, 23.5 cm × 25.4 cm (9 1⁄4 in × 10 in) hardcover by the Bodleian Library in 2018, and in a smaller paperback format the same year. A hardcover German edition was published by Stuttgart Hobbit Presse Klett-Cotta, also in 2018.[5]

Reception

Fafnir, the Nordic journal of science fiction and fantasy, wrote that McIlwaine is an authoritative editor who had assembled "an excellent textual and visual compendium". It noted some repetition between the essays and the catalogue, but admired McIlwaine's correlation of Tolkien's artwork with events in his life and his work on the three major Middle-earth books.[4]

The British Fantasy Society found the book "incredibly impressive" and the level of detail "astounding".[6] It stated that it surpassed earlier attempts at documenting Tolkien's creative process, with the inclusion of many unpublished personal photographs and private papers.[6]

The National Review described the exhibition as "the most thorough collection in years of Tolkien's wide-ranging creative gifts".[7] It notes the starting-point in 1914 where the 22-year-old Tolkien, about to go to the Western Front, spent his Christmas holiday writing the Kalevala-inspired The Story of Kullervo. The next year, one of his paintings depicted an Elvish city, Kor, and a poem next to the painting spoke of Valinor, the Undying Lands of The Silmarillion. The review praised McIlwaine for the exhibition's "tremendous vitality" achieved by putting Tolkien in "the full context of his life".[7]

The Claremont Review of Books stated that, seeing the English countryside after visiting the exhibition, "the significance of the most easily overlooked part of the Bodleian exhibition becomes clear: the family and personal mementos of a life lived in an England that was even then disappearing before Tolkien's eyes."[8] In its view, the book "demonstrated in glorious detail" many items of Tolkien's art not shown the exhibition, along with essays "that will become new standards, rich in detail while elegant in economy of prose".[8]

The Guardian's Samantha Shannon reported McIlwaine as saying she wanted exhibition visitors "to leave with the impression of the whole man and his work – not just Tolkien as the maker of Middle-earth, but as a scholar, a young professor, a father of four children".[9] Shannon wrote that McIlwaine had succeeded in this: "I am comforted to have glimpsed the man behind the myth, and I am more inspired than ever by the scope of his creation."[9]

The Daily Telegraph called the exhibition "tremendous ... an immersive experience". It noted that the Bodleian had assembled materials from the Marquette University collection as well as its own larger body of Tolkien papers.[10]

Christianity Today reported that the exhibition was "nearly comprehensive" but had one "glaring omission": "any mention of the author's devout, lifelong Christian faith."[11] It mentions Michael Ward's comment that Tolkien's faith is not obvious in Middle-earth, unlike his friend C. S. Lewis's Narnia, and concludes that "Only if we recognize Tolkien's deep Christian faith can we hope to understand the life and work of the 'Maker of Middle-earth'".[11]

The Norwegian American stated that there was a strong Norse connection in Tolkien's imagery, remarking upon his Father Christmas trudging like a Norwegian nisse through the snow under "a dark Northern sky", the "exploding riot of color" of his Aurora Borealis, and his "Conversation with Smaug", the dragon of The Hobbit "ablaze in fiery hues, hoarding his heaps of gold", which it found "reminiscent of Beowulf".[12]

References

- "Exhibition: Tolkien - Maker of Middle-earth - The Tolkien Society". The Tolkien Society. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- "About the Exhibition - Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth". The Bodleian Library. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- Kidd, Patrick (1 June 2018). "Exhibition review: Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth at the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford". The Times. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Cossio, Andoni (2019). "Book Review: Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth". Fafnir. 6 (2): 65–68.

- "Tolkien maker of Middle-Earth". WorldCat. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth by Catherine McIlwaine. Book review". The British Fantasy Society. 18 July 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Loconte, Joseph (18 August 2020). "The Maker of Middle-earth, in Gorgeous Detail". National Review. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Anderson, Bradley. "Visiting Tolkien's Middle-Earth". Claremont Review of Books. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Shannon, Samantha (31 May 2018). "How Tolkien created Middle-earth". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Garth, John (2 June 2018). "Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth, Bodleian Libraries, review: 'A once-in-a-generation event'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Ordway, Holly (21 August 2018). "The Maker of the Maker of Middle-earth". Christianity Today. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Hofmo, Victoria (9 July 2019). "J.R.R. Tolkien and the Norse connection". The Norwegian American. Retrieved 15 July 2020.