To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse is a 1927 novel by Virginia Woolf. The novel centres on the Ramsay family and their visits to the Isle of Skye in Scotland between 1910 and 1920.

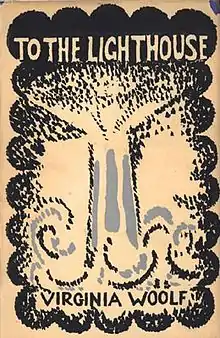

First edition | |

| Author | Virginia Woolf |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Vanessa Bell |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Modernism |

| Publisher | Hogarth Press |

Publication date | 5 May 1927 |

| Preceded by | Mrs Dalloway |

| Followed by | Orlando: A Biography |

Following and extending the tradition of modernist novelists like Marcel Proust and James Joyce, the plot of To the Lighthouse is secondary to its philosophical introspection. Cited as a key example of the literary technique of multiple focalization, the novel includes little dialogue and almost no direct action; most of it is written as thoughts and observations. The novel recalls childhood emotions and highlights adult relationships. Among the book's many tropes and themes are those of loss, subjectivity, the nature of art and the problem of perception.

In 1998, the Modern Library named To the Lighthouse No. 15 on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.[1] In 2005, the novel was chosen by TIME magazine as one of the one hundred best English-language novels since 1923.[2]

Plot summary

Part I: The Window

The novel is set in the Ramsays' summer home in the Hebrides, on the Isle of Skye. The section begins with Mrs Ramsay assuring her son James that they should be able to visit the lighthouse on the next day. This prediction is denied by Mr Ramsay, who voices his certainty that the weather will not be clear, an opinion that forces a certain tension between Mr and Mrs Ramsay, and also between Mr Ramsay and James. This particular incident is referred to on various occasions throughout the section, especially in the context of Mr and Mrs Ramsay's relationship.

The Ramsays and their eight children have been joined at the house by a number of friends and colleagues. One of them, Lily Briscoe, begins the novel as a young, uncertain painter attempting a portrait of Mrs. Ramsay and James. Briscoe finds herself plagued by doubts throughout the novel, doubts largely fed by the claims of Charles Tansley, another guest, who asserts that women can neither paint nor write. Tansley himself is an admirer of Mr Ramsay, a philosophy professor, and his academic treatises.

The section closes with a large dinner party. When Augustus Carmichael, a visiting poet, asks for a second serving of soup, Mr Ramsay nearly snaps at him. Mrs Ramsay is herself out of sorts when Paul Rayley and Minta Doyle, two acquaintances whom she has brought together in engagement, arrive late to dinner, as Minta has lost her grandmother's brooch on the beach.

Part II: Time Passes

The second section "Time passes" gives a sense of time passing, absence, and death. Ten years pass, during which the First World War begins and ends. Mrs Ramsay dies, as do two of her children – Prue dies from complications of childbirth, and Andrew is killed in the war. Mr Ramsay is left adrift without his wife to praise and comfort him during his bouts of fear and anguish regarding the longevity of his philosophical work. This section is told from an omniscient point of view and occasionally from Mrs. McNab's point of view. Mrs. McNab worked in the Ramsay's house since the beginning, and thus provides a clear view of how things have changed in the time the summer house has been unoccupied.

Part III: The Lighthouse

In the final section, "The Lighthouse", some of the remaining Ramsays and other guests return to their summer home ten years after the events of Part I. Mr Ramsay finally plans on taking the long-delayed trip to the lighthouse with daughter Cam(illa) and son James (the remaining Ramsay children are virtually unmentioned in the final section). The trip almost does not happen, as the children are not ready, but they eventually set off. As they travel, the children are silent in protest at their father for forcing them to come along. However, James keeps the sailing boat steady and rather than receiving the harsh words he has come to expect from his father, he hears praise, providing a rare moment of empathy between father and son; Cam's attitude towards her father changes also, from resentment to eventual admiration.

They are accompanied by the sailor Macalister and his son, who catches fish during the trip. The son cuts a piece of flesh from a fish he has caught to use for bait, throwing the injured fish back into the sea.

While they set sail for the lighthouse, Lily attempts to finally complete the painting she has held in her mind since the start of the novel. She reconsiders her memory of Mrs and Mr Ramsay, balancing the multitude of impressions from ten years ago in an effort to reach towards an objective truth about Mrs Ramsay and life itself. Upon finishing the painting (just as the sailing party reaches the lighthouse) and seeing that it satisfies her, she realises that the execution of her vision is more important to her than the idea of leaving some sort of legacy in her work.

Major themes

Complexity of experience

Large parts of Woolf's novel do not concern themselves with the objects of vision, but rather investigate the means of perception, attempting to understand people in the act of looking.[3] To be able to understand thought, Woolf's diaries reveal, the author would spend considerable time listening to herself think, observing how and which words and emotions arose in her own mind in response to what she saw.[4]

Complexity of human relationships

This examination of perception is not, however, limited to isolated inner-dialogues, but also analysed in the context of human relationships and the tumultuous emotional spaces crossed to truly reach another human being. Two sections of the book stand out as excellent snapshots of fumbling attempts at this crossing: the silent interchange between Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay as they pass the time alone together at the end of section 1, and Lily Briscoe's struggle to fulfill Mr. Ramsay's desire for sympathy (and attention) as the novel closes.[5]

Narration and perspective

The novel lacks an omniscient narrator (except in the second section: Time Passes); instead the plot unfolds through shifting perspectives of each character's consciousness. Shifts can occur even mid-sentence, and in some sense they resemble the rotating beam of the lighthouse itself. Unlike James Joyce's stream of consciousness technique, however, Woolf does not tend to use abrupt fragments to represent characters' thought processes; her method is more one of lyrical paraphrase. The lack of an omniscient narrator means that, throughout the novel, no clear guide exists for the reader and that only through character development can readers formulate their own opinions and views because much is ambiguous.[6][7]

Whereas in Part I, the novel is concerned with illustrating the relationship between the character experiencing and the actual experience and surroundings, part II, 'Time Passes', having no characters to relate to, presents events differently. Instead, Woolf wrote the section from the perspective of a displaced narrator, unrelated to any people, intending that events be seen in relation to time. For that reason the narrating voice is unfocused and distorted, providing an example of what Woolf called 'life as it is when we have no part in it.'[8][9] Major events like deaths of Mrs Ramsay, Prue, Andrew are related parenthetically, which makes the narration a kind of journal-entry. It is also possible that the house itself is the inanimate narrator of these events.[6]

Allusions to autobiography and actual geography

Woolf began writing To the Lighthouse partly as a way of understanding and dealing with unresolved issues concerning both her parents[10] and indeed there are many similarities between the plot and her own life. Her visits with her parents and family to St Ives, Cornwall, where her father rented a house, were perhaps the happiest times of Woolf's life, but when she was thirteen her mother died and, like Mr. Ramsay, her father Leslie Stephen plunged into gloom and self-pity. Woolf's sister Vanessa Bell wrote that reading the sections of the novel that describe Mrs Ramsay was like seeing her mother raised from the dead.[11] Their brother Adrian was not allowed to go on an expedition to Godrevy Lighthouse, just as in the novel James looks forward to visiting the lighthouse and is disappointed when the trip is cancelled.[12] Lily Briscoe's meditations on painting are a way for Woolf to explore her own creative process (and also that of her painter sister), since Woolf thought of writing in the same way that Lily thought of painting.[13]

Woolf's father began renting Talland House in St. Ives, in 1882, shortly after Woolf's own birth. The house was used by the family as a family retreat during the summer for the next ten years. The location of the main story in To the Lighthouse, the house on the Hebridean island, was formed by Woolf in imitation of Talland House. Many actual features from St Ives Bay are carried into the story, including the gardens leading down to the sea, the sea itself, and the lighthouse.[14]

Although in the novel the Ramsays are able to return to the house on Skye after the war, the Stephens had given up Talland House by that time. After the war, Virginia Woolf visited Talland House under its new ownership with her sister Vanessa, and Woolf repeated the journey later, long after her parents were dead.[14]

Publication history

Upon completing the draft of this, her most autobiographical novel, Woolf described it as 'easily the best of my books' and her husband Leonard thought it a "'masterpiece' ... entirely new 'a psychological poem'".[15] They published it together at their Hogarth Press in London in 1927. The first impression of 3000 copies of 320 pages measuring 7 1⁄2 by 5 inches (191 by 127 mm) was bound in blue cloth. The book outsold all Woolf's previous novels, and the proceeds enabled the Woolfs to buy a car.

Bibliography

- Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse, (London: Hogarth, 1927) First edition; 3000 copies initially with a second impression in June.

- Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse, (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1927) First US edition; 4000 copies initially with at least five reprints in the same year.

- Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse (Wordsworth Classics, 1994), with introduction and notes by Nicola Bradbury, ISBN 978-1853260919

Adaptations

- To the Lighthouse, a 1983 telefilm starring Rosemary Harris, Michael Gough, Suzanne Bertish, and Kenneth Branagh.

- To the Lighthouse, a 15-minute Drama, BBC Radio 4 11/08/2014 - 15/08/2014 dramatised by Linda Marshall Griffiths

- To the Lighthouse, a 2017 opera composed by Zesses Seglias to an English libretto by Ernst Marianne Binder. Premiered at the Bregenz Festival.

Footnotes

- "100 Best Novels". Random House. 1999. Retrieved 11 January 2010. This ranking was by the Modern Library Editorial Board of authors.

- "All-Time 100 Novels". Time. 6 January 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Davies p13

- Davies p40

- Welty, Eudora (1981). Forward to To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf. New York: Harvest. pp. vii–xii.

- Flint, Kate (25 May 2016). "An introduction to To the Lighthouse". The British Library – Discovering Literature: 20th century.

- Henke, Suzanne; Eberly, David (2007). Virginia Woolf and Trauma: Embodied Texts. New York: Pace University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9780944473795.

- Woolf, V. 'The Cinema"

- Raitt pp88-90, quote referencing Woolf, Virginia (1966). "The Cinema". Collected Essays II. London: Hogarth. pp. 267–272.

- Panken, Virginia Woolf and the "lust of creation", p.141

- New York Times article

- The preceding paragraph is based on facts in Nigel Nicolson, Virginia Woolf, Chapter One, which is reprinted here. These facts can also be found in Phyllis Rose, Introduction to A Voyage Out, Bantam Books, 1991, p. xvi

- Panken, op.cit., p.142

- Davies p1

- Woolf 1980, p. 123.

References

- Davies, Stevie (1989). Virginia Woolf To the Lighthouse. Great Britain: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-077177-8.

- Raitt, Suzanne (1990). Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf. ISBN 0-7450-0823-2.

- Dick, Susan; Virginia Woolf (1983). "Appendix A". To the Lighthouse: The Original Holograph Draft. Toronto, Londo: University of Toronto Press.

- Woolf, Virginia (1980). Bell, Anne Olivier; McNeillie, Andrew (eds.). The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Volume III: 1925–1930. London: Hogarth. ISBN 0-7012-0466-4.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Virginia Woolf |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to To the Lighthouse. |

- To the Lighthouse at Faded Page (Canada)

- To the Lighthouse at Project Gutenberg Australia (US text, slightly different from the UK text)

- Spark Notes study guide

- Woolf Online: An Electronic Edition and Commentary of Virginia Woolf's 'Time Passes'.

- To the Lighthouse at the British Library