Thomas Dudley

Thomas Dudley (12 October 1576 – 31 July 1653) was a colonial magistrate who served several terms as governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Dudley was the chief founder of Newtowne, later Cambridge, Massachusetts, and built the town's first home. He provided land and funds to establish the Roxbury Latin School, and signed Harvard College's new charter during his 1650 term as governor. Dudley was a devout Puritan who was opposed to religious views not conforming with his. In this he was more rigid than other early Massachusetts leaders like John Winthrop, but less confrontational than John Endecott.

Thomas Dudley | |

|---|---|

| Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony | |

| In office 1634–1635 | |

| Preceded by | John Winthrop |

| Succeeded by | John Haynes |

| In office 1640–1641 | |

| Preceded by | John Winthrop |

| Succeeded by | Richard Bellingham |

| In office 1645–1646 | |

| Preceded by | John Endecott |

| Succeeded by | John Winthrop |

| In office 1650–1651 | |

| Preceded by | John Endecott |

| Succeeded by | John Endecott |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 October 1576 Yardley Hastings, Northamptonshire, England |

| Died | 31 July 1653 (aged 76) Roxbury, Massachusetts Bay Colony |

| Spouse(s) | Dorothy Yorke

(m. 1603; died 1643)Katherine Hackburne (m. 1644) |

| Father | Roger Dudley |

| Profession | Colonial administrator, governor |

| Signature |  |

The son of a military man who died when he was young, Dudley saw military service himself during the French Wars of Religion, and then acquired some legal training before entering the service of his likely kinsman the Earl of Lincoln. Along with other Puritans in Lincoln's circle, Dudley helped organize the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, sailing with Winthrop in 1630. Although he served only four one-year terms as governor of the colony, he was regularly in other positions of authority.

Dudley's daughter Anne Bradstreet (1612–1672) was a prominent early American poet. One of the gates of Harvard Yard, which existed from 1915 to 1947, was named in his honor, and Harvard's Dudley House is named for the family, as is the town of Dudley, Massachusetts.

Early years

Thomas Dudley was born in Yardley Hastings, a village near Northampton, England, on 12 October 1576, to Roger and Susanna (Thorne) Dudley.[1] The family has long asserted connections to the Sutton-Dudleys of Dudley Castle (Duke of Northumberland, Earls of Warwick and Leicester, Viscounts Lisle, and Barons Dudley); there is a similarity in their coats of arms,[2] but association beyond probable common ancestry has not yet been conclusively demonstrated.[3][4] Roger Dudley, a captain in the English army, was apparently killed in battle. It was for some time believed he was killed in the 1590 Battle of Ivry,[5] but Susanna Dudley is known already to have been widowed by 1588. The 1586 battle of Zutphen has also been suggested as the occasion of Roger Dudley's death.[3]

Like many other young men of good birth Thomas Dudley became a page, in his case in the household of William, Baron Compton at nearby Castle Ashby.[3] Later he raised a company of men following a call to arms by Queen Elizabeth, and served in the English army led by Sir Arthur Savage fighting with King Henry IV of France during the French Wars of Religion. He fought the Spanish at the Siege of Amiens in 1597 which in September surrendered and was the final action of the war.[3]

After he was discharged from his military service, Dudley returned to Northamptonshire.[6] He then entered the service of Sir Augustine Nicolls, a relative of his mother's, as a clerk.[7][8] Nicolls, a lawyer and later a judge, was recognized for his honesty at a time when many judges were susceptible to bribery and other malfeasance.[9] He was also sympathetic to the Puritan cause; the exposure to legal affairs and Nicolls' religious views probably had a significant influence on Dudley. After Nicolls' sudden death in 1616, Dudley took a position with Theophilus Clinton, 4th Earl of Lincoln, serving as a steward responsible for managing some of the earl's estates. Although there is a likely blood connection, the reason for the appointment may be that Dudley's soldier grandfather Henry had served under Edward Clinton, 1st Earl of Lincoln. The earl's estate in Lincolnshire was a center of Nonconformist thought, and Dudley was already recognized for his Puritan virtues by the time he entered the earl's service.[10] According to Cotton Mather's biography of Dudley, he successfully disentangled a legacy of financial difficulties bequeathed to the earl, and the earl consequently came to depend on Dudley for financial advice.[11] Dudley's services were not entirely pecuniary in nature: he is also said to have had an important role in securing the engagement of Clinton to Lord Saye's daughter.[12] In 1622, Dudley acquired the assistance of Simon Bradstreet who was eventually drawn to Dudley's daughter Anne. The two were married six years later, when she was 16.[13]

Dudley was briefly out of Lincoln's service between about 1624 and 1628. During this time he lived with his growing family in Boston, Lincolnshire, where he likely was a parishioner at St Botolph's Church, where John Cotton preached. The Dudleys were known to be back on Lincoln's estate in 1628, when his daughter Anne came down with smallpox and was treated there.[14]

Massachusetts Bay Colony

In 1628 Dudley and other Puritans decided to form the Massachusetts Bay Company, with a view toward establishing a Puritan colony in North America. Dudley's name does not appear on the land grant issued to the company that year, but he was almost certainly involved in the formative stages of the company, whose investors and supporters included many individuals in the Earl of Lincoln's circle.[15] The company sent a small group of colonists led by John Endecott to begin building a settlement, called Salem, on the shores of Massachusetts Bay; a second group was sent in 1629.[16] The company acquired a royal charter in April 1629, and later that year made the critical decision to transport the charter and the company's corporate governance to the colony. The Cambridge Agreement, which enabled the emigrating shareholders to buy out those that remained behind, may have been written by Dudley.[17] In October 1629 John Winthrop was elected governor, and John Humphrey was chosen as his deputy.[16][18] However, as the fleet was preparing to sail in March 1630, Humphrey decided he would not leave England immediately, and Dudley was chosen as deputy governor in his place.[19]

Dudley and his family sailed for the New World on the Arbella, the flagship of the Winthrop Fleet, on 8 April 1630 and arrived in Salem Harbour on 22 June.[20] Finding conditions at Salem inadequate for establishing a larger colony, Winthrop and Dudley led forays into the Charles River watershed, but were apparently unable to immediately agree on a site for the capital.[21] With limited time to establish themselves, and concerns over rumors of potential hostile French action, the leaders decided to distribute the colonists in several places in order to avoid presenting a single target for hostilities. The Dudleys probably spent the winter of 1630–31 in Boston, which was where the leadership chose to stay after its first choice, Charlestown, was found to have inadequate water.[22] A letter Dudley wrote to the Countess of Lincoln in March 1631 narrated the first year's experience of the colonists that arrived in Winthrop's fleet in an intimate tone befitting a son or suitor as much as a servant.[23] It appeared in print for the first time in a 1696 compilation of early colonial documents by Joshua Scottow.[24]

Founding of Cambridge

In the spring of 1631 the leadership agreed to establish the colony's capital at Newtowne (near present-day Harvard Square in Cambridge), and the town was surveyed and laid out. Dudley, Simon Bradstreet, and others built their houses there, but to Dudley's anger, Winthrop decided to build in Boston. This decision caused a rift between Dudley and Winthrop—it was serious enough that in 1632 Dudley resigned his posts and considered returning to England.[25] After the intercession of others, the two reconciled and Dudley retracted his resignations. Winthrop reported that "[e]ver after they kept peace and good correspondency in love and friendship."[26] During the dispute, Dudley also harshly questioned Winthrop's authority as governor for a number of actions done without consulting his council of assistants.[27] Dudley's differences with Winthrop came to the fore again in January 1636, when other magistrates orchestrated a series of accusations that Winthrop had been overly lenient in his judicial decisions.[28]

In 1632 Dudley, at his own expense, erected a palisade around Newtowne (which was renamed Cambridge in 1636) that enclosed 1,000 acres (400 ha) of land, principally as a defense against wild animals and Indian raids. The colony agreed to reimburse him by imposing taxes upon all of the area communities.[26] The meetings occasioned by this need are among the first instances of a truly representative government in North America,[29] when each town chose two representatives to advise the governor on the subject. This principle was extended to govern the colony as a whole in 1634, the year Dudley was first elected governor.[26] During this term the colony established a committee to oversee military affairs and to manage the colony's munitions.[30]

The colony came under legal threat in 1632, when Sir Ferdinando Gorges, attempting to revive an earlier claim to the territory, raised issues of the colony's charter and governance with the Privy Council of King Charles I. When the colony's governing magistrates drafted a response to the charges raised by Gorges, Dudley was alone in opposing language referring to the king as his "sacred majesty", and to bishops of the Church of England as "Reverend Bishops".[31] Although a quo warranto writ was issued in 1635 calling for the charter to be returned to England, the king's financial straits prevented it from being served, and the issue eventually died out.[32]

Anne Hutchinson affair

In 1635, and for the four following years, Dudley was elected either as deputy governor or as a member of the council of assistants. The governor in 1636 was Henry Vane, and the colony was split over the actions of Anne Hutchinson. She had come to the colony in 1634, and began preaching a "covenant of grace" following her mentor, John Cotton, while most of the colony's leadership, including Dudley, Winthrop, and most of the ministers, espoused a more Legalist view ("covenant of works"). This split divided the colony, since Vane and Cotton supported her.[33] At the end of this colonial strife, called the Antinomian Controversy, Hutchinson was banished from the colony, and a number of her followers left the colony as a consequence.[34] She settled in Rhode Island, where Roger Williams, also persona non-grata in Massachusetts over theological differences, offered her shelter.[35] Dudley's role in the affair is unclear, but historians supportive of Hutchinson's cause argue that he was a significant force in her banishment,[36] and that he was unhappy that the colony did not adopt a more rigid stance or ban more of her followers.[37]

Vane was turned out of office in 1637 over the Hutchinson affair and his insistence on flying the English flag over the colony's fort — many Puritans felt that the Cross of St George on the flag was a symbol of popery and was thus anathema to them.[38] Vane was replaced by Winthrop, who then served three terms.[39] According to Winthrop, concerns over the length of his service led to Dudley's election as governor in 1640.[40]

Although Dudley and Winthrop clashed with each other on a number of issues, they agreed on the banning of Hutchinson, and their relationship had some significant positive elements. In 1638 Dudley and Winthrop were each granted a tract of land "about six miles from Concord, northward".[41] Reportedly, Winthrop and Dudley went to the area together to survey the land and select their parcels. Winthrop, then governor, graciously deferred to Dudley, then deputy governor, to make the first choice of land. Dudley's land became Bedford, and Winthrop's Billerica.[41] The place where the two properties met was marked by two large stones, each carved with the owner's name; Winthrop described the spot as the "'Two Brothers', in remembrance that they were brothers by their children's marriage".[42]

Other political activities

During Dudley's term of office in 1640, many new laws were passed. This led to the introduction the following year of the Massachusetts Body of Liberties, a document that contains guarantees that were later placed in the United States Bill of Rights. During this term he joined moderates, including John Winthrop, in opposing attempts by the local clergy to take a more prominent and explicit role in the colony's governance.[43] When he was again governor in 1645 the colony threatened war against the expansionist Narragansetts, who had been making war against the English-allied Mohegans. This prompted the Narragansett leader Miantonomi to sign a peace agreement with the New England colonies which lasted until King Philip's War broke out 30 years later.[44] Dudley also presided over the acquittal of John Winthrop in a trial held that year; Winthrop had been charged with abuses of his power as a magistrate by residents of Hingham the previous year.[45]

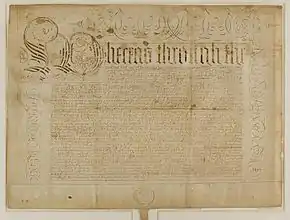

In 1649 Dudley was appointed once again to serve as a commissioner and president of the New England Confederation, an umbrella organization established by most of the New England colonies to address issues of common interest; however, he was ill (and aging, at 73), and consequently unable to discharge his duties in that office.[46] Despite the illness, Dudley was elected governor for the fourth and last time in 1650.[47] The most notable acts during this term were the issuance of a new charter for Harvard College,[48] and the judicial decision to burn The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption, a book by Springfield resident William Pynchon that expounded on religious views heretical to the ruling Puritans. Pynchon was called upon to retract his views, but he chose to return to England instead of facing the magistrates.[49]

During most of his years in Massachusetts, when not governor, Dudley served as either deputy governor or as one of the colony's commissioners to the New England Confederation.[50] He also served as a magistrate in the colonial courts,[51] and sat on committees that drafted the laws of the colony.[52] His views were conservative, but he was not as strident in them as John Endecott. Endecott notoriously defaced the English flag in 1632, an act for which he was censured and deprived of office for one year.[53] Dudley sided with the moderate faction on the issue, which believed the flag's depiction of the Cross of St George had by then been reduced to a symbol of nationalism.[54]

Nathaniel Morton, an early chronicler of the Plymouth Colony, wrote of Dudley, "His zeal to order appeared in contriving good laws, and faithfully executing them upon criminal offenders, heretics, and underminers of true religion. He had a piercing judgment to discover the wolf, though clothed with a sheepskin."[55] Early Massachusetts historian James Savage wrote of Dudley that "[a] hardness in public, and rigidity in private life, are too observable in his character".[55] In a more modern historical view, Francis Bremer observes that Dudley was "more precise and rigid than the moderate Winthrop in his approach to the issues facing the colonists".[56]

Founding of Harvard and Roxbury Latin

Who staid thy feeble sides when thou wast low,

Who spent his state, his strength, and years with care,

Anne Bradstreet, verse written on Harvard Yard's Dudley Gate[57]

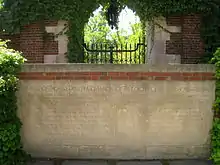

In 1637 the colony established a committee "to take order for a new college at Newtown".[58] The committee consisted of most of the colony's elders, including Dudley. In 1638, John Harvard, a childless colonist, bequeathed to the colony his library and half of his estate as a contribution to the college, which was consequently named in his honor. The college charter was first issued in 1642, and a second charter was issued in 1650, signed by then-Governor Thomas Dudley,[58] who also served for many years as one of the college's overseers. Harvard University's Dudley House, now only an administrative unit located in Lehman Hall after the actual house was torn down, is named in honor of the Dudley family.[59] Harvard Yard once had a Dudley Gate bearing words written by his daughter Anne;[57] it was torn down in the 1940s to make way for construction of Lamont Library.[60] A fragment remains in Dudley Garden, behind Lamont Library, including a lengthy inscription in stone.[61][62]

In 1643, Reverend John Eliot established a school at Roxbury. Dudley, who was then living in Roxbury, gave significant donations of both land and money to the school, which survives to this day as the Roxbury Latin School.[63]

Family and legacy

Dudley married Dorothy Yorke in 1603, and with her had five or six children. Samuel, the first, also came to the New World, and married Winthrop's daughter Mary in 1633, the first of several alliances of the Dudley-Winthrop family.[65] He later served as the pastor in Exeter, New Hampshire.[66] Daughter Anne married Simon Bradstreet, and became the first poet published in North America.[67][68] Patience, Dudley's third child, married colonial militia officer Daniel Denison. The fourth child, Sarah, married Benjamin Keayne, a militia officer. This union was an unhappy one, and resulted in the first reported instance of divorce in the colony; Keayne returned to England and repudiated the marriage. Although no formal divorce proceedings are known, Sarah eventually married again,[69] to Job Judkins, by whom she bore five children. Mercy, the last of his children with Dorothy, married minister John Woodbridge.[67]

Dudley may have had another son, though most historians seem to think the evidence is too slim. A “Thomas Dudley” was awarded degrees from Emmanuel College, Cambridge University, in 1626 and 1630, and some historians have argued this is a son of Dudley. Also, Dudley was referred to as “Thomas Dudley Senior” on a lone occasion in 1637.[70]

Dorothy Yorke died 27 December 1643 at 61 years of age, and was remembered by her daughter Anne in a poem:[71]

Here lies,

A worthy matron of unspotted life,

A loving mother and obedient wife,

A friendly neighbor, pitiful to poor,Whom oft she fed and clothed with her store;

Dudley married his second wife, the widow Katherine (Deighton) Hackburne, descendant of the noble Berkeley, Lygon and Beauchamp families,[72] in 1644. She is also a direct descendant of eleven of the twenty-five barons who acted as sureties for John Lackland on the Magna Carta.[73] They had three children, Deborah, Joseph, and Paul.[67] Joseph served as governor of the Dominion of New England and of the Province of Massachusetts Bay.[74] Paul (not to be confused with Joseph's son Paul, who served as provincial attorney general) was for a time the colony's register of probate.[67]

In 1636 Dudley moved from Cambridge to Ipswich, and in 1639 moved to Roxbury.[75][76] He died in Roxbury on 31 July 1653, and was buried in the Eliot Burying Ground there. Dudley, Massachusetts is named for his grandsons Paul and William, who were its first proprietors.[77]

The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation owns a parcel of land in Billerica called Governor Thomas Dudley Park.[78] The "Two Brothers" rocks are located in the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Bedford, in an area that has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Two Brothers Rocks-Dudley Road Historic District.[79]

Dudley Square

Dudley Square in Boston's Roxbury neighborhood was named after Dudley.[80] Proponents of an effort to rename the square noted that Dudley was "a leading politician in 1641", when the colony became the first to legally sanction slavery.[81] Conversely, Byron Rushing, former president of the Museum of African American History in Boston, stated, “I’ve really searched, and I’ve found no evidence that Dudley ever owned slaves."[82]

A non-binding advisory question was added to the November 5, 2019, municipal ballot for all Boston residents asking, "Do you support the renaming/changing of the name of Dudley Square to Nubian Square?"[80] Election night results show that the question was defeated.[83]

Mayor of Boston Marty Walsh subsequently announced that the question had "passed in the surrounding areas" near the square, and could be considered further by the city's Public Improvement Commission.[84] On December 19, 2019, the Public Improvement Commission unanimously approved changing the name of Dudley Square to Nubian Square.[85][86] Dudley station was renamed Nubian station in June 2020.[87]

Notes

- Anderson, p. 584

- Jones, pp. 3–10

- Richardson et al, p. 280

- Anderson, p. 585

- Jones, p. 3

- Jones, p. 24

- Kellogg, p. 3

- Jones, p. 25

- Jones, pp. 25–26

- Jones, pp. 31–32

- Jones, p. 40

- Jones, p. 42

- Kellogg, pp. 11–12

- Kellogg, p. 8

- Jones, pp. 44–46, 55

- Hurd, p. vii

- Jones, p. 73

- Bailyn, pp. 18–19

- Jones, pp. 59–60

- Jones, pp 64,75

- Jones, p. 78

- Jones, pp. 83–84

- Female Piety in Puritan New England: The Emergence of Religious Humanism, Amanda Porterfield, p. 89

- "Massachusetts: or The First Planters of New-England, The End and Manner of Their Coming Thither, and Abode There: In Several Epistles (1696)". University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- Moore, p. 283

- Moore, p. 284

- Jones, pp. 109–110

- Bremer (2003), p. 245

- Moore, p. 285

- Moore, p. 286

- Bremer (2003), p. 234

- Bremer (2003), p. 240

- Moore, pp. 287–288

- Battis, pp. 232–48

- Moore, p. 288

- Jones, p. 226

- Bremer (2003), p. 298

- Moore, pp. 317–318

- Moore, pp. 6,320

- Moore, p. 289

- Jones, p. 251

- Jones, p. 252

- Jones, p. 271

- Jones, p. 334

- Bremer (2003), pp. 363–364

- Jones, p. 389

- Jones, p. 393

- Jones, p. 394

- Jones, p. 398

- Hurd, p. ix

- Hurd, p. x

- Jones, p. 264

- Bremer (2003), p. 238

- Bremer, p. 239

- Moore, p. 292

- Bremer and Webster (2006), p. 79

- Morison, p. 195

- Jones, p. 243

- Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 29, p. 365

- Bunting and Floyd, pp. 216,319–320

- Yael M. Saiger (5 May 2017). "Closing a Gate, Creating a Space". The Harvard Crimson. Trustees of The Harvard Crimson. OCLC 55062930. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- Rose Lincoln (2 September 2014). "Hidden Spaces: Secret garden". Harvard Gazette. Harvard University. ISSN 0364-7692. OCLC 837901863. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- Jones, p. 330

- See e.g. the Auden genealogy entry for Thomas Dudley Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, and Google image search for "Thomas Dudley"

- Jones, pp. 422,467

- Jones, p. 467

- Moore, pp. 295–296

- Kellogg, p. xii

- Jones, pp. 469–471

- Savage, James (2008). Genealogical Dictionary of the First Settlers of New England. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8063-0759-6.

- Jones, p. 318

- Ancestral Roots Of Certain American Colonists Who Came To America Before 1700, 8th edition, Frederick Lewis Weis, Walter Lee Sheppard, William Ryland Beall, Kaleen E. Beall, p.90

- http://www.brookfieldpublishingmedia.com/Ancestors/Im1/Deighton%20Katherine.aspx

- Moore, pp. 391–393

- Moore, p. 291

- Jones, p. 256

- Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, p. 12:412

- "Massachusetts DCR Property Listing" (PDF). Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "MACRIS listing for Two Brothers Rocks-Dudley Road" (PDF). Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- DeCosta-Klipa, Nik (19 September 2019). "Boston residents will get to vote on changing the name of Dudley Square. Here's why". Boston.com. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Daily Free Press Staff (6 November 2019). "Boston votes against renaming Dudley Square". The Daily Free Press. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- MacQuarrie, Brian (18 December 2019). "Dudley Square: at the intersection of Colonial history, African heritage". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- "BOSTON MUNICIPAL ELECTION NOVEMBER 2019". boston.gov. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Cotter, Sean Philip (15 November 2019). "Behind the 8 ball: Boston heads for City Council recount as margin just 8 votes". Boston Herald. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- adamg (19 December 2019). "Dudley Square officially gets renamed Nubian Square". Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Cotter, Sean Philip (19 December 2019). "Roxbury's Dudley Square renamed Nubian Square". Boston Herald. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Belcher, Jonathan. "Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district" (PDF). NETransit.

References

- Anderson, Robert Charles (1995). The Great Migration Begins: Immigrants to New England, 1620–1633. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 978-0-88082-120-9. OCLC 42469253.

- Bailyn, Bernard (1979). The New England Merchants in the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-61280-8. OCLC 257293935.

- Battis, Emery (1962). Saints and Sectaries: Anne Hutchinson and the Antinomian Controversy in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Bremer, Francis (2003). John Winthrop: America's Forgotten Founder. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514913-5. OCLC 237802295.

- Bremer, Francis; Webster, Tom (2006). Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America: a Comprehensive Encyclopedia. New York: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-678-1. OCLC 162315455.

- Bunting, Bainbridge; Floyd, Margaret Henderson (1985). Harvard: an Architectural History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-37290-0. OCLC 11650514.

- Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 29. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. 1981. OCLC 1751811.

- Hurd, Duane Hamilton (ed) (1890). History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Volume 1. Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis. OCLC 2155461.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Jones, Augustine (1900). The Life and Work of Thomas Dudley, the Second Governor of Massachusetts. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin. OCLC 123194823.

- Kellogg, D. B (2010). Anne Bradstreet. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson. ISBN 978-1-59555-109-2. OCLC 527702802.

- Moore, Jacob Bailey (1851). Lives of the Governors of New Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay. Boston: C. D. Strong. p. 273. OCLC 11362972.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1995) [1935]. The Founding of Harvard College. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-31451-1. OCLC 185403584.

- Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Historical Society, Volume 12. 1873. p. 412. OCLC 1695300.

- Richardson, Douglas; Everingham, Kimball; Faris, David (2004). Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8063-1750-2. OCLC 55848314.

Further reading

- Dudley, Dean (1848). The Dudley Genealogies and Family Records. Boston, MA: self-published. OCLC 3029090.

- Governor Thomas Dudley Family Association (1894). The First Annual Meeting of the Governor Thomas Dudley Association, Boston, Ma., 17 Oct. 1893. Boston, MA: self-published. OCLC 9274332.