Theodore Vejtehi

Theodore Vejtehi (Hungarian: Vejtehi Tivadar, Romanian: Teodor Voitici; died 1327), also Theodore Csanád, was an influential lord in the Kingdom of Hungary at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, who ruled the Banate of Severin (Hungarian: Szörénység) de facto independently of the central royal power.[1]

Theodore Vejtehi | |

|---|---|

| Ban of Severin (debated) | |

| Reign | c. 1291–1316 |

| Predecessor | Lawrence (?) |

| Successor | John Vejtehi (?) |

| Died | 1327 |

| Noble family | gens Csanád |

| Issue

John Nicholas a daughter | |

| Father | Dominic |

Family

Theodore (II) was born into the gens Csanád as the son of Dominic, who was mentioned by a record in 1256. He had a brother Ernye. The kindred, according to the tradition, originated from chieftain Csanád, a relative of Stephen I of Hungary and founder and first ispán of Csanád County which named after him. Theodore's direct ancestor was Bogyoszló. Theodore appeared in the contemporary sources first in 1285 in a false diploma, when he, alongside Ernye, participated in the county assembly at Csanád. He had three children: John, Nicholas and an unidentified daughter, who married royal notary Gál Omori.[2]

In 1256, the Vejtehi branch of the genus owned possessions and vineyards in Csanád, Temes, Syrmia Counties and in the Duchy of Macsó and Požega County beyond the river Sava. Furthermore, they also had lands in Győr, Moson and Vas Counties at the other end of the kingdom.

Lord of Severin

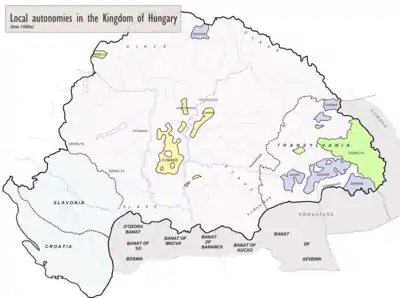

Theodore preceded Basarab I of Wallachia as lord of Severin as Basarab was first mentioned by one of the royal charters of Charles I of Hungary only on 26 July 1324. However, very little is known about Theodore's reign. During the period of feudal anarchy, when the kingdom was in a state of constant anarchy since the rule of Ladislaus IV, Theodore autonomously governed the territory of the Banate of Severin, between the Lower Danube and the Southern Carpathians by usurping royal prerogatives in his dominion. Thus historian Gyula Kristó considered him as one of the so-called "oligarchs" or "provincial lords".[1] Before the death of Andrew III of Hungary and extinction of the Árpád dynasty, the last known person, who held the title Ban of Severin, was a certain Lawrence, son of Voivode Lawrence in 1291,[3] after that, as Pál Engel says, the dignity vanished by the end of the 13th century and only restored by Charles I with the appointment of Denis Szécsi from the gens Balog in 1335.[4] However Szécsi was already appointed castellan of Zsidóvár and Miháld (today Jidoara and Mehadia in Romania) in 1322 which presumably was the antecedent position of the restored dignity.[5] Thus there is no proof that Theodore had ever held the office of Ban of Severin, although some charters referred to him with the "ban" prefix.[6]

When Charles I signed an alliance with his cousin Rudolph III of Austria in Pressburg (today Bratislava, Slovakia) on 24 August 1304, Theodore was among the barons and prelates, who did the same thing in a royal charter, this source confirms that the Vejtehi family had supported Charles during the struggle for the Hungarian throne.[7] Theodore, as most of the provincial lords, only guaranteed Charles with his support just then, when the Anjou prince finally took the upper hand over his rivals.[8]

The Vejtehi family, Theodore and his sons, governed their province from Miháld Castle (today in ruins near Mehadia) which presumably was built by themselves. There are no other known castles owned by Theodore,[9] but György Györffy argued that they also had to possess the nearby fortress of Severin.[6] Theodore gradually built up foreign relations with the Despotate of Vidin, which supported him in the struggle against King Charles I,[10] who was determined to unite the kingdom following his victory over the rival pretenders, Wenceslaus and Otto. Following the Battle of Rozgony in 1312, Charles defeated the oligarchs one by one. The Vejtehis rebelled against the King in 1316 alongside the Borsa, Ákos and Kán kinreds in Tiszántúl and Transylvania.[11][12]

Decline

According to a royal charter from 1317, Charles' loyal general Paul Szécsi led a campaign in autumn 1316 to besiege Miháld which defended by John Vejtehi, son of Theodore. By that time Theodore was already in custody and taken tied up before the castle and dragged along the walls at the heels of a horse to persuade John to surrender the fort. In spite of all these, Szécsi was unable to take Miháld, however defeated the army of despot Michael Shishman in the nearby battlefield.[13] Szécsi sent several Hungarian and Bulgarian prisoners of war to the royal court of Charles.[6] According to Pál Engel, who dated the first siege to 1314, Charles I personally led a next royal campaign against the Vejtehis following his victories in Transylvania at the end of 1321 or early 1322. The castle was besieged and successfully occupied by the King and general Martin, son of Bogár, a former familiaris of oligarch Matthew Csák. John Vejtehi was pardoned and allowed to settle down his estate in Temes County, while Denis Szécsi, Paul's brother was installed castellan. In the following months Szécsi expanded his influence along the Lower Danube by taking Görény Castle from the Bulgarians.[14]

Because of the elusive chronology of the events, Gyula Kristó had a different theory about the campaign against the Vejtehi dominion in his 2003 essay. As Kristó says the significance of Miháld has appreciated when Charles transferred his residence from Buda to Temesvár (today Timișoara, Romania) in early 1315 and the struggle followed that. He also did not accept Charles' personal presence.[15] According to Kristó the second campaign took place in 1321.[16]

Theodore survived his downfall. In 1322 Theodore (now mentioned as magister) and his two sons donated the estates of Szentlászló and Szentmargit (today parts of Makó, Csongrád County) to his son-in-law, Gál Omori. All three of them returned to the loyalty to King Charles.[6] Theodore died in 1327. Some of his sons' lands were confiscated in 1332. As Györffy claims, his brother-in-law Ivan the Russian fled to Bulgaria following the dissolution of the Vejtehi realm, where he served as general and diplomat in the tsar's court (Michael Shishman was elected Tsar in 1323).[11] Opposite him, historian István Vásáry points to the lack of clear evidence and the large time span between the Hungarian noble and the Bulgarian general named Ivan the Russian.[17]

References

- Kristó 1979, p. 144.

- Engel: Genealógia (Genus Csanád 1., Bogyoszló branch)

- Zsoldos 2011, p. 50.

- Engel 1996, p. 32.

- Engel 1996, p. 46.

- Györffy 1964, p. 539.

- Kristó 1999, p. 42.

- Kristó 1999, p. 53.

- Kristó 1979, p. 159.

- Kristó 1979, p. 189.

- Györffy 1964, p. 540.

- Kristó 1979, p. 206.

- Engel 1988, pp. 104–105.

- Engel 1988, p. 130.

- Kristó 2003, p. 328.

- Kristó 2003, p. 343.

- Vásáry 2005, pp. 124–125.

Sources

- Engel, Pál (1988). "Az ország újraegyesítése. I. Károly küzdelmei az oligarchák ellen (1310–1323) [Reunification of the Realm. The Struggles of Charles I Against the Oligarchs (1310–1323)]". Századok (in Hungarian). Magyar Történelmi Társulat. 122 (1–2): 89–146. ISSN 0039-8098.

- Engel, Pál (1996). Magyarország világi archontológiája, 1301–1457, I [Secular Archontology of Hungary, 1301–1457, Volume I] (in Hungarian). História, MTA Történettudományi Intézete. ISBN 963-8312-44-0.

- Györffy, György (1964). "Adatok a románok XIII. századi történetéhez és a román állam kezdeteihez [Contributions to the 13th-century History of the Romanians and the Origin of the Romanian State]". Történelmi Szemle (in Hungarian). Hungarian Academy of Sciences. 7 (3–4): 537–568. ISSN 0040-9634.

- Kristó, Gyula (1979). A feudális széttagolódás Magyarországon [Feudal Anarchy in Hungary] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-1595-4.

- Kristó, Gyula (1999). "I. Károly király főúri elitje (1301–1309) [The Aristocratic Elite of King Charles I, 1301–1309]". Századok (in Hungarian). Magyar Történelmi Társulat. 133 (1): 41–62. ISSN 0039-8098.

- Kristó, Gyula (2003). "I. Károly király harcai a tartományurak ellen (1310–1323) [The Struggles of Charles I Against the Oligarchs (1310–1323)]". Századok (in Hungarian). Magyar Történelmi Társulat. 137 (2): 297–347. ISSN 0039-8098.

- Vásáry, István (2005). "The Tatars fade away from Bulgaria and Byzantium, 1320–1354". Cumans and Tatars: Oriental military in the pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83756-9.

- Zsoldos, Attila (2011). Magyarország világi archontológiája, 1000–1301 [Secular Archontology of Hungary, 1000–1301] (in Hungarian). História, MTA Történettudományi Intézete. ISBN 978-963-9627-38-3.