Theodore Freeman

Theodore Cordy "Ted" Freeman (February 18, 1930 – October 31, 1964), was an American aeronautical engineer, U.S. Air Force officer, test pilot, and NASA astronaut. Selected in the third group of NASA astronauts in 1963, he was killed a year later in the crash of a T-38 jet, marking the first fatality among the NASA Astronaut Corps. At the time of his death, he held the rank of captain.[1][2]

Theodore C. Freeman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Theodore Cordy Freeman February 18, 1930 Haverford, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | October 31, 1964 (aged 34) |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Nationality | United States |

| Alma mater | University of Delaware (attended one year) U.S. Naval Academy, (B.S. 1953) University of Michigan, (M.S. 1960) |

| Occupation | Test pilot, aeronautical engineer |

| Space career | |

| NASA Astronaut | |

| Rank | |

| Selection | 1963 NASA Group 3 |

| Missions | None |

Early years

Born in Haverford, Pennsylvania, on February 18, 1930, Freeman was named after the man who raised his father (Theodore Cullen Donovan), as well as his maternal grandfather (Thomas Cordy Wilson).[3] He was one of five children.[4] Raised in Lewes, Delaware, he attended Lewes Elementary School from 1936 to 1944. His father was a farmer and his brother a carpenter, and it seemed as if he would also have a blue collar career. When Freeman and his brother were young, they saved up money so they could take plane rides. He also was a part-time worker, helping to refuel the planes and work on them. He spent most of his money on flying lessons, and with over 450 hours of flying on his training record, earned his pilot's license by the age of 16. "I sort of grew up at the airport," Freeman said.[5]

Freeman played baseball and football in high school. While playing football, he was hit hard and his teeth were knocked out of alignment. He was the president of the school's student and the local chapter of the National Honor Society; he graduated as an honors student ranked third in his class in 1948.[6][7]

He was a Boy Scout and he earned the rank of First Class.[8]

Education

During his senior year of high school, Freeman completed the application to the U.S. Naval Academy. He passed the scholarship portion but failed the medical portion due to his crooked teeth. He was told if he straightened them out he would be accepted the next year.[6]

During that year, Freeman attended the University of Delaware at Newark to further his education. He also made some money by spotting schools of fish for local fishermen. Freeman had an operation to fix his teeth, which included grinding his teeth down, then wore braces for several months to finish the effort. He was admitted to the U.S. Naval Academy Class of 1953 on June 17, 1949.[9] Freeman graduated from Annapolis in 1953 with a Bachelor of Science degree. In 1960, he received a Master of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from the University of Michigan.[10]

Military and NASA career

Freeman, about his astronaut duties.[11]

Freeman elected to enter the U.S. Air Force and took flight training at Hondo Air Force Base and Bryan Air Force Base, Texas and at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada.[12] He was awarded his pilot wings in February 1955, shortly after being promoted to first lieutenant, then served in the Pacific and at George Air Force Base, California. He was promoted to captain in June 1960 while pursuing his master's degree at the University of Michigan and then went to Edwards Air Force Base, California, in February 1960 as an aerospace engineer.[13]

Freeman graduated from both the Air Force's Experimental Test Pilot School (Class 62A) and Aerospace Research Pilot School (Class IV) courses. He elected to serve with the Air Force. His last Air Force assignment was as a flight test aeronautical engineer and experimental flight test instructor at the ARPS at Edwards AFB in the Mojave Desert.[10]

Freeman served primarily in performance flight testing and stability testing areas; he logged more than 3,300 hours flying time, including more than 2,400 hours in jet aircraft. Freeman was one of the third group of astronauts selected by NASA in October 1963 and was assigned the responsibility of aiding the development of boosters.[14]

Death

On the morning of October 31, 1964, after a delay caused by fog, Freeman piloted a T-38A Talon from St. Louis to Houston. He was returning from McDonnell training facilities in St. Louis and crashed during final approach to landing at Ellington Air Force Base in Houston. There were reports of geese due to the fog, one of which flew into the port-side air intake of his NASA-modified T-38 jet trainer, causing the engine to flame out.[15] Flying shards of Plexiglas entered the jet engine during the crash.[16]

Freeman attempted to land on the runway, but realized he was too short and might hit military housing. He banked away from the runway and ejected. The jet had nosed down a considerable amount, and he ejected nearly horizontally. Freeman's parachute did not deploy in time, and he died upon impact with the ground. His skull was fractured and he had severe chest injuries.[17]

Personal life

Freeman was survived by his wife Faith Clark Freeman and one daughter, Faith Huntington.[10] Faith Freeman first heard of her husband's death when a reporter came to her house: NASA subsequently ensured that in the case of future astronaut deaths, their families were informed by other astronauts as quickly as possible.[18] He was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery. Five astronauts were pallbearers at the funeral.[19]

Honors

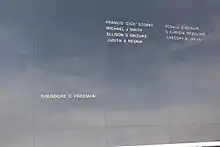

The Clear Lake City-County Freeman Branch Library of the Harris County Public Library and Houston Public Library systems is named in memory of Freeman. An artificial island off Long Beach is also named for him.[20] This is one of the four "Astronaut Islands" built in Long Beach Harbor during the late 1960s as unsinkable platforms for oil drilling; the others were named Grissom, White and Chaffee, in honor of the astronauts killed in the Apollo 1 fire.[21][22] A crater on the far side of the Moon was temporarily named Freeman crater by the Apollo 8 crew.[23] The Theodore C. Freeman Highway in Lewes, Delaware, an approach road to the Cape May–Lewes Ferry which carries U.S. Route 9, was named after him by a resolution of the Delaware Senate on December 21, 1965. A plaque commemorating Freeman was unveiled at the Lewes terminal of the Cape May–Lewes Ferry on June 18, 2014, with Governor Jack Markell and family members of Freeman in attendance at the ceremony.[24][25]

Books

Oriana Fallaci's If the Sun Dies, a book on the early days of the American space program, features an account of Freeman.[26]

See also

Notes

- "Astronaut killed in plane crash". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. November 1, 1964. p. 1.

- "Jet trainer crash kills astronaut". Pittsburgh Press. UPI. November 1, 1964. p. 1 – via Google News.

- Burgess, Doolan & Vis 2008, p. 5.

- "Mother of Astronaut Named Delaware's Mother of the Year". The News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware. March 25, 1965. p. 29 – via Newspapers.com.

- Burgess, Doolan & Vis 2008, p. 6.

- Burgess, Doolan & Vis 2008, p. 7.

- "Lewes Mourns its Astronaut". The News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware. November 2, 1964. p. 30 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Theodore C. Freeman at scouting.org". Boy Scouts of America. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Burgess, Doolan & Vis 2008, p. 8.

- "Theodore Freeman Biography" (PDF). NASA. November 1964. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- "Theodore C. Freeman's quotation". astronautmemorial.net. Archived from the original on August 17, 2007. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Burgess, Doolan & Vis 2008, p. 11.

- Burgess, Doolan & Vis 2008, p. 13.

- Collins 2001, p. 108.

- Burgess, Doolan & Vis 2008, pp. 3, 20.

- Burgess, Doolan & Vis 2008, p. 20.

- Burgess, Doolan & Vis 2008, pp. 21–22, 25.

- Collins 2001.

- "Space Hero's Last Trip – To Arlington". The San Francisco Examiner. San Francisco, California. UPI. November 4, 1964. p. 23 – via Newspapers.com.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Island Freeman

- "Oil Biz: A Touch of Disney". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Los Angeles Times Service. May 27, 1978. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com.

- Gore, Robert J. (May 19, 1978). "Is This An Apartment Complex...or an Oil Drilling Island?". Tampa Bay Times. St. Petersburg, Florida: Los Angeles Times. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com.

- Robert, John A. (December 26, 1968). "Moon Crater Named after Freeman". The News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Delaware Code – 123rd General Assembly – Chapter 489". State of Delaware. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- MacArthur, Ron (June 23, 2014). "Freeman Highway named after American hero". Cape Gazette. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- Fallaci, Oriana (1966). If the Sun Dies. New York: Atheneum.

References

- Burgess, Colin; Doolan, Kate; Vis, Bert (2008). Fallen Astronauts: Heroes Who Died Reaching the Moon. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska. ISBN 978-0-8032-1332-6.

- Collins, Michael (2001) [1974]. Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut's Journeys. New York: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 978-0-8154-1028-7. OCLC 45755963.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Theodore Freeman. |