The Tenant

The Tenant (French: Le locataire) is a 1976 French psychological horror film directed by Roman Polanski, starring Polanski, Isabelle Adjani, Melvyn Douglas, and Shelley Winters. It is based upon the 1964 novel Le locataire chimérique by Roland Topor[3] and is the last film in Polanski's "Apartment Trilogy", following Repulsion and Rosemary's Baby. It was entered into the 1976 Cannes Film Festival.[4] The film had a total of 534,637 admissions in France.[5]

| The Tenant (Le locataire) | |

|---|---|

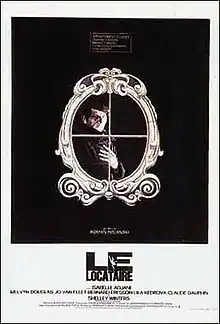

Original film poster | |

| Directed by | Roman Polanski |

| Produced by | Andrew Braunsberg |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | The Tenant by Roland Topor |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Philippe Sarde |

| Cinematography | Sven Nykvist |

| Edited by | Françoise Bonnot |

Production company | Marianne Productions |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 126 mins |

| Country | France |

| Language |

|

| Box office | $5.1 million[1][2] |

Plot summary

Trelkovsky (Roman Polanski), a quiet and unassuming man, rents an apartment in Paris whose previous tenant, Egyptologist Simone Choule, attempted to commit suicide by throwing herself out of the window and through a pane of glass below. He visits Simone in the hospital but finds her entirely in bandages and unable to talk. Whilst still at Simone’s bedside, Trelkovsky meets Simone's friend, Stella (Isabelle Adjani), who has also come to visit. Stella is overwhelmed with emotion and begins talking to Simone, who looks towards her visitors and lets out a disturbing cry. The matron insists they leave, having already informed Trelkovsky that he may not speak to Choule. Trelkovsky tries to comfort Stella but dares not say that he never knew Simone, instead pretending to be another friend. They leave together and go out for a drink and a movie (1973's Enter The Dragon), where they fondle each other. Outside the theatre they part ways. Later, Trelkovsky calls up the hospital to enquire about Simone, and is told she has died.

As Trelkovsky occupies the apartment he is chastised repeatedly by his neighbors and landlord, Monsieur Zy (Melvyn Douglas), for hosting a party with his friends, apparently having a woman over, making too much noise in general, and not joining in on a petition against another neighbor. Trelkovsky attempts to adapt to his situation, but is increasingly disturbed by the apartment and the other tenants. He frequently sees his neighbors standing motionless in the toilet room (which he can see from his own window), and discovers a hole in the wall with a human tooth stashed inside. He discusses this with his friends, who do not find things strange and belittle him for not standing up to his neighbours. He visits the apartment of one of his work friends, who plays a marching band record at a spitefully loud volume. A neighbour politely asks him to turn down the music, as his wife is ill and trying to sleep. Trelkovsky turns the record down, but his friend tells the neighbour that he will play his music as he wants, and that he does not care about his sick wife.

He receives a visit from one Georges Badar (Rufus), who secretly loved Simone and has believed her to be alive and well. Trelkovsky updates and comforts the man and spends the night out with him. He receives a postcard that Badar had posted before realising Simone had died. Frequenting the nearby café which Simone also patronised, he is recognized as the new tenant of her apartment. The owner pressures him into having Simone's regular order, which is then always given to him without being ordered, against his preferences. They are always out of his preferred choice of cigarette, Gauloises, so he develops a habit of ordering Marlboros, which Simone used to order. Nobody has any idea why Simone was suicidal.

Trelkovsky becomes severely agitated and enraged when his apartment is robbed, while his neighbors and the concierge (Shelley Winters) continue to berate him for making too much noise, and his landlord warns him not to inform the police of the burglary. Suffering from fever and bad dreams, he wakes up one morning to find his face made up. He buys a wig and women's shoes and goes on to dress up (using Simone's dress which he had found in a cupboard) and sit still in his apartment in the dead of night. He suspects that Zy and neighbors are trying to subtly change him into the last tenant, Simone, so that he too will kill himself. He becomes hostile and paranoid in his day-to-day environment (snapping at his friends, slapping a child in a park) and his mental state progressively deteriorates. He has visions of his neighbors playing football with a human head, finds the toilet covered in hieroglyphs, and looking across the courtyard, sees himself standing at his apartment window, looking into the bathroom with binoculars. Trelkovsky runs off to Stella for comfort and sleeps over, but in the morning after she has left for work, he concludes that she too is in on his neighbors' plot, and proceeds to vandalise and burgle her apartment before departing.

At night he is hit by an elderly couple driving a car. He is not injured too seriously, but receives a sedative injection from the doctor due to his odd behavior — he perceives the elderly couple as his landlord Zy and wife, and accuses them of trying to murder him. The couple returns him to his apartment. A deranged Trelkovsky dresses up again as a woman and throws himself out of the apartment window in the manner of Simone Choule, before what he believes to be a clapping, cheering audience composed of his neighbors. The suicide attempt wakes up his neighbors, who call the police and attempt to restrain him. He crawls away from them back to his apartment, and jumps out the window a second time moments after the police arrive.

In the final scene, Trelkovsky is bandaged up in the same fashion as Simone Choule, in the same hospital bed. From his perspective, we see his and Stella's own visit to Simone. Trelkovsky then lets out the same disturbing cry as Simone did in the earlier scene.

Cast

- Roman Polanski – Trelkovsky

- Isabelle Adjani – Stella

- Melvyn Douglas – Monsieur Zy

- Jo Van Fleet – Madame Dioz

- Bernard Fresson – Scope

- Rufus – Georges Badar

- Shelley Winters – The Concierge

- Lila Kedrova – Madame Gaderian

- Patrice Alexsandre – Robert

- Romain Bouteille – Simon

- Josiane Balasko – Viviane

- Claude Dauphin – Husband at the accident

- Claude Piéplu – Neighbor (as Claude Pieplu)

- Jacques Monod – Cafe Owner

- Jean-Pierre Bagot – Policeman

- Jacques Rosny – Jean-Claude

- Michel Blanc – Scope's Neighbor

- Eva Ionesco – Bettina, Mme Gaderian's Daughter

- Albert Delpy – Neighbour

Production notes

Although typically labelled as the third part of Polanski's so-called "Apartment Trilogy", this came about more by luck than by design. The film adaptation was originally to have been made by British director Jack Clayton, who was attached to the project around seven years before Polanski made it. According to Clayton's biographer Neil Sinyard, Clayton originally tried to make the film ca. 1969 for Universal Studios, from a script by Edward Albee, but this version never made it into production after the relationship between Albee and the studio soured. Paramount bought the rights on Clayton's advice in 1971. Clayton returned to the project in the mid-1970s, and a rough draft script by Christopher Hampton was written while Clayton was preparing The Great Gatsby. By the time Clayton had delivered Gatsby to Paramount in March 1974, he had learned from Robert Evans that Polanski was interested in the project and wanted to play the lead role. While Clayton was occupied preparing foreign language versions of Gatsby for the European market, Paramount studio head Barry Diller began negotiations with Polanski. Although Clayton later insisted that he was never specifically asked if he was still interested, and never said "no" to it, Diller wrongly assumed that Clayton had lost interest and transferred the project to Polanski, without asking Clayton. When he found out, Clayton called Diller in September 1974, expressing his dismay that Diller had given another director a film which (Clayton insisted) had been specifically purchased by the studio for him, and for doing so without consultation.[6]

While the main character is clearly paranoid to some extent, the film does not entirely reveal whether everything takes place in his head or if the strange events happening around him exist at least partially, contrary to the previous entries in Polanski's "apartment trilogy."[7][8][9]

Themes

Overview

In his review of the film for The Regrettable Moment of Sincerity, Adam Lippe writes: "Many would attest that The Pianist is Polanski's most personal work, given the obvious Holocaust subject matter, but look beneath the surface, and when the window curtains are drawn aside, Polanski's The Tenant shines brightest as the work closest to his being."[10]

Other than to the works of Franz Kafka (see below), the film's even more mysterious, ambiguous mood and atmosphere as to whether it belongs to either the horror or the psychological thriller genre has garnered it critical comparisons to both its contemporaries Don't Look Now (1973) by Nicolas Roeg[11] and Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980),[12] even more so than the previous two entries to Polanski's Apartment Trilogy. Given its production design, photography, and in how The Tenant crafts a creepily bizarre scenario of a group of neighbors appearing to be preying on a new tenant's life and conspire against him for that purpose, it has also been compared to the black comedy film Delicatessen (1991) by Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro, which also stars the French actor Rufus in a supporting role, just like The Tenant and The Shining seems to suggest a house as the malevolent source to the sinister deeds of its inhabitants, and is set in a post-apocalyptic future where all animals have died and the people of a remote decaying house resort to eating each of the house's successive new janitors.[13][14]

Kafka influence

Many critics have noted The Tenant's strong Kafkaesque theme, typified by an atmosphere that is absurdly over-burdened with anxiety, confusion, guilt, bleak humour, alienation, sexual frustration and paranoia. However, the film cannot be viewed as purely driven by a Kafkaesque motif because of the numerous references to Trelkovsky's delirium and heavy drinking. This allows for more than one interpretation.

Most of the action occurs within a claustrophobic environment where dark, ominous things occur without reason or explanation to a seemingly shy protagonist, whose perceived failings as a tenant are ruthlessly pursued by what Trelkovsky himself views as an increasingly cabalistic conspiracy. Minor infringements are treated as serious breaches of his tenancy agreement, and this apparent persecution escalates after he refuses to join his neighbours in a prejudiced campaign to oust a mother with a disabled child.

"The scheming plots over matters of extraordinary pettiness and inexplicable conspiracies that go on among the neighbours to gang up on others make The Tenant probably the first Kafkaesque horror film."[15]

"Much effect is derived from the absurdity of the scenario where all Trelkovsky wants to do is not bother anyone, yet everything Trelkovsky does is seen as an imposition."[16]

Critics have speculated[15] that the film's Kafkaesque atmosphere must be in part a reflection of Polanski's own Jewish experiences within a predominantly anti-Semitic environment. Trelkovsky is viewed with suspicion by almost every other character simply because he is a foreign national. For example, when he tries to report a robbery to the French police he is treated sceptically and told that as a foreigner he should not make trouble. Both the director and the protagonist are outsiders who strive ineffectually for acceptance in what they see as a corrupt and mysterious world.

Vincent Canby wrote in The New York Times: "Trelkovsky exists. He inhabits his own body, but it's as if he had no lease on it, as if at any moment he could be dispossessed for having listened to the radio in his head after 10 P.M. People are always knocking on his walls."[17]

According to Ulrich Behrens of Der Mieter (translated from the German):

"The film's title [of The Tenant] could be interpreted as follows: An alien is given the chance to rent an apartment for himself in a well-ordered world, however he may be evicted at any given time once the natives find him to be in violation of this world's well-ordered rules, or failing to properly internalize them. In the end, it is of little importance who is normal and who is insane. The individual's paranoia equals our well-ordered world's desire to persecute. Nobody can help Trelkovsky - he can't even help himself. In a disenchanted, jaded world with its fixed social order, the individual and one's autonomy have but one fate: Either submission and internalization of people's rules - or insanity. Which is no real choice. Here, the individual is always on the brink of annihilation, about to lose itself."[18]

Doomed cycle, loss of self, and social assimilation

The Tenant has been referred to as a precursor to Kubrick's The Shining (1980),[12] as another film where the lines between reality, madness, and the supernatural become increasingly blurry (the question usually asked with The Shining is "Ghosts or cabin fever?") as the protagonist finds himself doomed to cyclically repeat another person's nightmarish fall. Just like in The Shining, the audience is slowly brought to accept the supernatural by what at first seems a slow descent into madness, or vice versa: "The audience's predilection to accept a proto-supernatural explanation [...] becomes so pronounced that at Trelkovsky's break with sanity the viewer is encouraged to take a straightforward hallucination for a supernatural act."[19]

In his book Polanski and Perception, Davide Caputo has called the fact that in the end, Trelkovsky defenestrates himself not once, but twice "a cruel reminder of the film's 'infinite loop'"[20] of Trelkovsky becoming Mme. Choule meeting Trelkovsky shortly before dying in the hospital, a loop not unlike The Shining's explanation that Jack Torrance "has always been the Overlook's caretaker". Timothy Brayton of Antagony & Ecstasy likens this eternally looping cycle of The Tenant to the film's recurring Egyptian motifs:

"There is a recurrent motif of Egyptian hieroglyphics that remains unexplained in the film. Ancient Egyptian religious belief, it is important to note, was based on the notion that all things are the same all throughout history: not the same as Hinduism's conception that everything has happened before and will happen again, but more the belief that everything is always happening. The best I can come up with is to suppose that Trelkovsky, whether in his mind or in reality, is always the same as Simone. He does not become her, so much as we finally reach a point where the distinction between the two of them is no longer important. Either way, the result is the same: there is no Trelkovsky. To someone whose life had been as traumatic as Polanski's, that idea might well have been an attractive one."

— Timothy Brayton (Antagony & Ecstasy), Apartment house fools[21]

Steve Biodrowski of Cinefantastique writes: "THE TENANT is short on typical horror movie action: there are no monsters, and there is little in the way of traditional suspense. That's because the film is not operating on the kind of fear that most horror films exploit: fear of death. Instead, THE TENANT's focus is on an equally disturbing fear: loss of identity."[22] In his review of the film for The Regrettable Moment of Sincerity, Adam Lippe writes of Trelkovsky's surroundings sinisterly shaping him into an echo of the past: "Coming from a Nazi-occupied childhood, Polanski no doubt uses his character's identity crisis to illustrate society's ability to shape and mold the uniqueness of its members, whether they like it or not."[10] Similarly, Dan Jardine of Apollo Guide writes: "Polanski seems to be studying how people, in our isolating world, increasingly mould themselves to their environment, sometimes to the point where their individual identity is absorbed into the world around them. The longer he is in the building, the more Trelkovsky begins to lose sight of where his internal sense of his 'self' ends, and his social identity begins."[23]

"What happens to The Tenant? Is poor Trelkovsky haunted by ghosts or does he turn insane? Does a (mysteriously) hostile environment drive him to commit suicide, or do the necessities of a cold reality break a tender soul? Could Trelkovsky be identical to Simone Choul from the beginning? Are we even witnessing Simone Choul's very own death hallucination, with Trelkovsky as nothing but a figment of her dying mind?" [24]

— Wollo (Die besten Horrorfilme.de), Der Mieter (German review)

Because of how little we get to know of Trelkovsky's life prior to his applying for the apartment and moving in, only to become an echo of former tenant Mme. Choule because of his frail, almost inexistent personality's weak resistance to either her ghost or his bullying neighbors as if he has always been Mme. Choule and always will be, the film has also been referred to as an early precursor to Fight Club (1999), a film where the final twist reveals it to be about a case of split personality.[10]

Isolation and claustrophobia

A recurring theme with Polanski's films, but especially pronounced in The Tenant, is that of the protagonist as a silent, isolated observer in hiding. As Brogan Morris writes in Flickering Myth: "One of Roman Polanski's recurring motifs has always been the horror of the apartment space. It was as recently as his last film, Carnage, and in a crucial sequence of his masterful The Pianist: it's from an apartment window which Szpilman can do nothing but watch atrocities unfold outside. The fascination is there most obviously, though, in Polanski's 'Apartment Trilogy' [...]. And The Tenant, a blackly comedic meta-horror, is perhaps Polanski's ultimate use of the apartment as a claustrophobic, paranoid zone of terror."[25]

"The Tenant also makes an interesting film to read in term of Roman Polanski's own life – he, like the character he plays, is a Pole who went to live in Paris very shortly after the film was made. His other horror films – Repulsion, Rosemary's Baby – like The Tenant, see the apartment as a home of paranoia and madness. You could extend the analogy further and compare Repulsion, Rosemary's Baby and The Tenant to Polanski's The Pianist, where Adrien Brody's protagonist, a Jew living in Poland under Nazi occupation, is reduced to hiding a pitiful, starving existence hiding in cubbyholes and the bombed-out ruins of buildings where he cannot be sure whether the people he encounters are friend or foe or will betray him. Polanski himself grew up in the Krakow ghettos as a Jewish child under the Nazi occupation and survived by hiding in the countryside and with other families after his parents were taken to the concentration camps, so perhaps one can see the very personal nature of the recurrent themes of isolation, paranoia and the feeling that the apartment is an alien world in his work."

— Richard Scheib (Moira: Science Fiction, Horror and Fantasy Film Review), THE TENANT (Le Locataire)[15]

Sexual deviance and repression

Related to the aforementioned kafkaesque guilt and the theme of identity loss, another theme that appears throughout the film is that of sexual deviance and Trelkovsky's increasing trespassing of traditional gender roles, as he more and more turns into an echo of former tenant Mme. Choule. German reviewer Andreas Staben writes: "And again, [Polanski] tells of sexual repression, and in Polanski's astounding, unpretentious performance, Trelkovsky's escape into the identity of Simone Choule appears as a consequential closure of all three films [of the Apartment Trilogy]. Other than was maybe the case still with Repulsion, there can be no talk whatsoever of a psycho-pathological case study anymore: Here, the individual is entirely wiped out and all that remains is the horror of facing a pure void."[26]

"In The Tenant, Roman Polanski explores again the psychic terrain of guilt, dread, paranoia, fears of sexual inadequacy and hysteria he made so familiar in Repulsion, Rosemary's Baby, Macbeth, and Chinatown. [...] [T]he confusion of sexual roles is more pronounced here than anywhere else in [Polanski's] work. The slightly decadent and fetishistic, but innocent, bedtime games of Cul-de-sac have developed into the signs of a basic confusion concerning sexual identity. T.'s acquisition of feminine costume and habits speaks to a repressed and disturbing need. He is not attracted to women, in fact cannot perform sexually when Stella (Isabelle Adjani) takes him home. In this respect he is again the counterpart of Simone Schoul who, he is told, was never interested at all in men. As he is drawn more completely into the idea of becoming this woman, T. pauses to speculate about what defines him. If a man loses an arm, he wonders, does the arm or the remaining body define his selfhood? How much can a man lose, change, or give away and still remain 'himself'? Or, to paraphrase the advertisers, does the cigarette make the man?"

— Norman Hale (Movietone News, no. 52, October 1976, p. 38-39), Review: Tenant[27]

Reception

Although The Tenant was poorly received on its release, with Roger Ebert declaring it "not merely bad -- it's an embarrassment,"[28] it has since become a cult favorite.[29][30][31] Bruce Campbell named it one of his favorite horror movies in an interview with Craig Ferguson, as well as calling it the scariest film he had ever seen.[32] The film holds an 88% Certified fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes with 32 reviews.

References

- "The Tenant". Box Office Mojo.

- http://www.jpbox-office.com/fichfilm.php?id=8166

- Vincent Canby (21 June 1976). "The Tenant". The New York Times.

- "Festival de Cannes: The Tenant". Festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- "The Tenant". Jpbox-office-com.

- Neil Sinyard, Jack Clayton (Manchester University Press, 2000), p. 212

- Meyncke, Amanda Mae (2 July 2008). "Roman Polanski's Apartment Trilogy Still As Artful As Ever". Film.com.

- Thompson, Anne (25 July 2007). "Rush Hour 3: Ratner Casts Polanski as Sadistic Cop". Variety.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2009.

- "A Polanski Guide To Urban Living". Cinemaretro.com. 19 August 2009.

- Lippe, Adam. The Tenant, The Regrettable Moment of Sincerity, 21 January 2009

- Castle, Robert (2004). Disturbing Movies: or the Flip Side of the Real, Bright Lights Film Journal, 30 April 2004

- Del Valle, David (2010). Wig of a Poet: Un Polanski Rorschach, ACIDEMIC: Journal of Film and Media, 2010

- Hanke, Ken (2006). Delicatessen, Mountain Xpress, 26 March 2008

- Taunton, Matthew. "Delicatessen, The Tenant and Le Crime de Monsieur Lange", chapter in Taunton's book Fictions Of The City: Class, Culture and Mass Housing in London and Paris (PDF excerpt), Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, p. 37-48

- Scheib, Richard. THE TENANT (Le Locataire), Moira: Science Fiction, Horror and Fantasy Film Review

- Lorefice, Mike (2003). Le Locataire (The Tenant, France/USA - 1976), Raging Bull Movie Reviews, 8 December 2003

- Canby, Vincent (21 June 1976). "The Screen: Roman Polanski's 'The Tenant' Arrives". The New York Times. 125 (43, 248): 37.

- "Der Titel des Films reicht bis an eine Interpretation heran, die so lauten könnte: Da kam einer in diese wohl geordnete Welt, und man gab ihm die Chance, sich einen Platz zu "mieten". Dieses "Mietverhältnis" aber kann jederzeit gekündigt werden, wenn sich der "Mieter" nicht den festgefügten Verhältnissen anpasst, sie verinnerlicht. So bleibt die Frage, wer hier eigentlich wahnsinnig und wer normal ist, am Schluss fast bedeutungslos. Der Verfolgungswahn des einzelnen reiht sich ein in die Verfolgungsmentalität einer "wohl" geordneten Welt. Niemand kann Trelkovsky wirklich helfen – nicht einmal er selbst. In einer scheinbar aufgeklärten, aber eben auch maßlos abgeklärten Welt mit einer feststehenden Ordnung hat das Individuelle, das subjektive Eigenhaben nur eine Alternative: Unterwerfung und Internalisierung – oder Wahnsinn. Also keine Alternative. Es steht immer vor der Kippe, vor dem Verlust seiner selbst." Behrens, Ulrich. "Der Mieter". Filmzentrale (in German). Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- Smuts, Aarons (2002). Sympathetic spectators: Roman Polanski's Le Locataire (The Tenant, 1976), Kinoeye: New Perspectives On European Film, Vol. 2, Issue 3, 4 February 2002

- Caputo, Davide (2012). Polanski and Perception: The Psychology of Seeing and the Cinema of Roman Polanski, Intellect Books, 2012, ISBN 1841505528, p. 159

- Brayton, Timothy (2007). Apartment house fools, Antagony & Ecstasy, 6 May 2007

- Biodrowski, Steve (2009). The Tenant (1976), Cinefantastique, 11 December 2009

- Jardine, Dan. Tenant, The, Apollo Guide

- "Was passiert im 'Mieter'? Sucht Geisterspuk den armen Trelkovsky heim oder verfällt er schlicht dem Irrsinn? Treibt ihn seine ihm feindlich gesinnte (warum?) Umwelt in einen Freitodversuch oder zerbricht der schüchterne, in sich gekehrte junge Mann an der kalten Realität? Ist Trelkovsky etwa mit Simone Clouche identisch? Oder werden wir gar Zeuge eines Traums, den die sterbende Simone Clouche träumt, und Trelkovsky ist nichts anderes als die Traumgestalt ihrer selbst?" Wollo. Der Mieter, Die Besten Horrorfilme.de

- Morris, Brogan (2013). Leeds International Film Festival 2013 Review – The Tenant (1976), Flickering Myth, 18. November 2013

- "Und wieder erzählt er auf von sexueller Repression, wobei Trelkovskys Flucht in die Identität Simone Choules in Polanskis erstaunlicher, gänzlich unmanirierter Darstellung als konsequenter Endpunkt aller drei Filme erscheint. Von einer psychopathologischen Fallstudie kann hier anders als vielleicht noch bei Ekel endgültig keine Rede mehr sein: Das Individuum wird aufgelöst und es bleibt nur der Schrecken angesichts des blanken Nichts." Staben, Andreas. Der Mieter, filmstarts.de

- Hale, Norman (1976). Review: Tenant, Movietone News, no. 52, October 1976, p. 38-39

- https://rogerebert.com/reviews/the-tenant-1976

- https://ew.com/article/2012/05/17/cannes-polanski-as-victim-rust-and-bone

- http://originaltrilogy.com/topic/The-Tenant-Polanski-1976-BD25-RELEASED/id/16504

- http://www.ifi.ie/film/the-tenant/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Enz6R_Ji0Tg