The Human Abstract (poem)

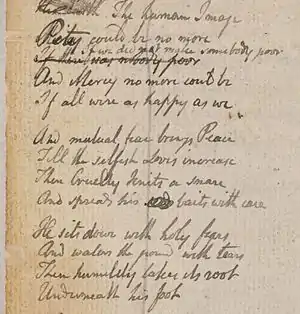

"The Human Abstract" is a poem written by the English poet William Blake. It was published as part of his collection Songs of Experience in 1794.[2] The poem was originally drafted in Blake's notebook and was later revised for as part of publication in Songs of Experience. Critics of the poem have noted it as demonstrative of Blake's metaphysical poetry and its emphasis on the tension between the human and the divine.

_The_Human_Abstract.jpg.webp)

_The_Human_Abstract_-_detail.jpg.webp)

_The_Human_Abstract_-_detail.jpg.webp)

_The_Human_Abstract_-_detail.jpg.webp)

_The_Human_Abstract.jpg.webp)

Poem

Pity would be no more,

If we did not make somebody Poor:

And Mercy no more could be,

If all were as happy as we;

And mutual fear brings peace;

Till the selfish loves increase.

Then Cruelty knits a snare,

And spreads his baits with care.

He sits down with holy fears,

And waters the ground with tears:

Then Humility takes its root

Underneath his foot.

Soon spreads the dismal shade

Of Mystery over his head;

And the Caterpillar and Fly,

Feed on the Mystery.

And it bears the fruit of Deceit,

Ruddy and sweet to eat;

And the Raven his nest has made

In its thickest shade.

The Gods of the earth and sea,

Sought thro' Nature to find this Tree

But their search was all in vain:

There grows one in the Human Brain[3]

Context and interpretation

The poem was engraved on a single plate as a part of the Songs of Experience (1794) and reprinted in Gilchrist's Life of Blake in the second volume 1863/1880 from the draft in the Notebook of William Blake (p. 107 reversed, see the example on the right), where the first title of the poem The Earth was erased and The human Image substituted.[4] The title The Human Abstract appeared first in the Songs of Innocence and of Experience. In the commentary to his publication of the Songs of Innocence and of Experience, D. G. Rossetti described this poem as one of "very perfect and noble examples of Blake's metaphysical poetry".[5]

The illustration shows a gowned old man with a long beard who kneels with his legs outspread. He raises his arms to grip the ropes as if he tries to free himself. There is a tree trunk with a broad base on the right and the edge of another on the left. The colour of the sky suggests sunrise or sunset. A muddy river runs along the lower edge of the design in front of the man. The picture portrays the supreme God of Blake's mythology and the creator of the material world, whom Blake named "Urizen" (probably from your reason), struggling with his own nets of religion, under the Tree of Mystery, which symbolically "represents the resulting growth of religion and the priesthood (the Catterpillar and the Fly), feeding on its leaves".[6]

The previous title of the poem "The Human Image" shows clearly that it is a counterpart to "The Divine Image" in the Songs of Innocence. There is a great difference between two worlds: of Innocence and of Experience. In "The Divine Image" of Innocence Blake establishes four great virtues: mercy, pity, peace, and love, where the last one is the greatest and embraces the other three. These four virtues represent God as well as a Man:

For Mercy Pity Peace and Love,

Is God our Father dear:

And Mercy Pity Peace and Love,

Is Man His child and care.

For Mercy has a human heart

Pity, a human face:

And Love, the human form divine,

And Peace, the human dress.[7]— "The Divine Image", lines 5-12

However, as Robert F. Gleckner pointed out, “in the world of experience such a human-divine imaginative unity is shattered, for the Blakean fall, as is well known, is a fall into division, fragmentation, each fragment assuming for itself the importance (and hence the benefits) of the whole. Experience, then, is fundamentally hypocritical and acquisitive, rational and non-imaginative. In such a world virtue cannot exist except as a rationally conceived opposite to vice.”[8]

Blake made two more attempts to create a counterpart poem to The Divine Image of Innocence. One of them, A Divine Image, was clearly intended for Songs of Experience, and was even etched, but not included into the main corpus of the collection:[note 1][9]

_Detail.jpg.webp)

Cruelty has a Human Heart

And Jealousy a Human Face

Terror, the Human Form Divine

And Secrecy, the Human Dress

The Human Dress, is forged Iron

The Human Form, a fiery Forge.

The Human Face, a Furnace seal'd

The Human Heart, its hungry Gorge.[10]— "A Divine Image"

There are the explicit antitheses in this poem and The Divine Image of the Songs of Innocence. "The poem's discursiveness, its rather mechanical, almost mathematical simplicity make it unlike other songs of experience; the obviousness of the contrast suggests a hasty, impulsive composition..."[11]

The four virtues of The Divine Image (mercy, pity, peace, and love) that incorporated the human heart, face, form, and dress were abstracted here from the corpus of the divine, become selfish and hypocritically disguise their true natures, and perverted into cruelty, jealousy, terror, and secrecy.

Another poem dealing with the same subject "I heard an Angel singing..." exists only in draft version and appeared as the eighth entry of Blake's Notebook, p. 114, reversed, seven pages and about twenty poems before "The Human Image" (that is the draft of "The Human Abstract"). "Blake's intention in 'The Human Abstract' then was to analyze the perversion while making it clear at the same time that imaginatively (to the poet) it was a perversion, rationally (to fallen man) it was not. In 'A Divine Image' he had simply done the former. 'I heard an Angel singing...' was his first attempt to do both, the angel speaking for 'The Divine Image', the devil for 'A Divine Image'":[12]

I heard an Angel singing

When the day was springing

Mercy Pity Peace

Is the worlds release

Thus he sung all day

Over the new mown hay

Till the sun went down

And haycocks looked brown

I heard a Devil curse

Over the heath & the furze

Mercy could be no more

If there was nobody poor

And pity no more could be

If all were as happy as we

At his curse the sun went down

And the heavens gave a frown

Down pourd the heavy rain

Over the new reapd grain

And Miseries increase

Is Mercy Pity Peace[13]

In a draft version of "The Human Abstract" (under the title "The human Image") the word "Pity" of the first line is written instead of the word "Mercy". The second line "If we did not make somebody poor" in the first version was written above the struck-through line "If there was nobody poor".

[Mercy] Pity could be no more

[If there was nobody poor]

If we did not make somebody poor

And Mercy no more could be

If all were as happy as we

In the second stanza the word "baits" is a replacement of the deleted word "nets":

And mutual fear brings Peace

Till the selfish Loves increase

Then Cruelty knits a snare

And spreads his [nets] baits with care

Third, fourth and fifth stanzas arranged exactly as in the last etched version, however with no punctuation marks:

He sits down with holy fears

And waters the ground with tears

Then humility takes its root

Underneath his foot

Soon spreads the dismal shade

Of Mystery over his head

And the catterpillar & fly

Feed on the Mystery

And it bears the fruit of deceit

Ruddy & sweet to eat

And the raven his nest has made

In its thickest shade

The last quatrain of the poem is the replacement of the following passage:

The Gods of the Earth & Sea

Sought thro nature to find this tree

But their search was all in vain

[Till they sought in the human brain]

There grows one in the human brain

They said this mistery never shall cease

The priest [loves] promotes war and the soldier piece

There souls of men a bought & sold

And [cradled] milk fed infancy [is sold] for gold

And youth[s] to slaughter houses led

And [maidens] beauty for a bit of bread

As was observed by the scholars, the ideas of the poem correspond with some other works of Blake which show deeper insight. For example:

"A very similar description of the growth of the Tree is found in Ahania (engr. 1795), chap, iii, thus condensed by Swinburne:[14] 'Compare the passage . . . where the growth of it is defined; rooted in the rock of separation, watered with the tears of a jealous God, shot up from sparks and fallen germs of material seed; being after all a growth of mere error, and vegetable (not spiritual) life; the topmost stem of it made into a cross whereon to nail the dead redeemer and friend of men.'".[15]

Here is the mentioned fragment from Chap: III of The Book of Ahania:

A Tree hung over the Immensity

3: For when Urizen shrunk away

From Eternals, he sat on a rock

Barren; a rock which himself

From redounding fancies had petrified

Many tears fell on the rock,

Many sparks of vegetation;

Soon shot the pained root

Of Mystery, under his heel:

It grew a thick tree; he wrote

In silence his book of iron:

Till the horrid plant bending its boughs

Grew to roots when it felt the earth

And again sprung to many a tree.

4: Amaz'd started Urizen! when

He beheld himself compassed round

And high roofed over with trees

He arose but the stems stood so thick

He with difficulty and great pain

Brought his Books, all but the Book

Of iron, from the dismal shade

5: The Tree still grows over the Void

Enrooting itself all around

An endless labyrinth of woe!

6: The corse of his first begotten

On the accursed Tree of Mystery:

On the topmost stem of this Tree

Urizen nail'd Fuzons corse.[16]— The Book of Ahania 3:8-35

Sampson[15] noticed that "the 'Tree of Mystery' signifies 'Moral Law'", and cited the relevant passage from Blake's Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion:

He [Albion] sat by Tyburns brook, and underneath his heel, shot up!

A deadly Tree, he nam'd it Moral Virtue, and the Law

Of God who dwells in Chaos hidden from the human sight.

The Tree spread over him its cold shadows, (Albion groand)

They bent down, they felt the earth and again enrooting

Shot into many a Tree! an endless labyrinth of woe![17]— Jerusalem 2:14-19

Gleckner concluded his analysis with the statement that the poem "The Human Abstract", as a whole, is “a remarkably ambitious experiment in progressive enrichment, and a revealing document for the study of Blake's two contrary states of the human soul.” [11]

Musical settings

- David A. Axelrod (b.1931), USA: The human abstract. No. 6 from Songs of Experience, for orchestra. Rec. Capitol stereo SKAO-338 (1969)[18]

- Timothy Lenk (b. 1952), USA: The human abstract. No. 12 from Songs of Innocence and of Experience, for tenor and bass soli, flute (piccolo), clarinet (and bass clarinet) and violin, 1977[19]

- Gerard Victory (1921 –1995), Ireland: The human abstract. No. 5 from Seven Songs of Experience, for soprano and tenor soli, and SATB a capella, 1977/78[20]

- Mike Westbrook (b. 1936), UK: The human abstract, for jazz ensemble and singing, Rec. 1983[21]

- William Brocklesby Wordsworth (1908 –1988), UK: Pity would be no more (The human abstract), No. 4 from A Vision, for women's voices (SSA), strings and piano, Op. 46 (1950)[22]

See also

- The Human Abstract (song)

- The Human Abstract (band) (metal band)

Notes

- The poem only appeared in copy BB of the combined Songs of Innocence and of Experience.

References

- Morris Eaves; Robert N. Essick; Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "Songs of Innocence and of Experience, copy Y, object 47 (Bentley 47, Erdman 47, Keynes 47) "The Human Abstract"". William Blake Archive. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- William Blake. The Complete Poems, ed. Ostriker, Penguin Books, 1977, p.128.

- Blake 1988, p. 27

- Sampson, p. 134.

- Gilchrist, II, p. 27.

- G. Keynes, p. 47.

- Blake 1988, pp. 12-13

- Gleckner, p. 374.

- "Songs of Innocence and of Experience". William Blake Archive. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- Blake 1988, p. 32

- Gleckner, p. 379.

- Gleckner, p. 376.

- Blake 1988, pp. 470-471

- Swinburne, p. 121

- Sampson, p. 135.

- Blake 1988, pp. 86-87

- Blake 1988, p. 174

- Fitch, p. 9

- Fitch, p. 133

- Fitch, p. 235

- Fitch, p. 242

- Fitch, p. 252

Works cited

- Blake, William (1988). Erdman, David V. (ed.). The Complete Poetry and Prose (Newly revised ed.). Anchor Books. ISBN 0385152132.

- Fitch, Donald (1990). Blake set to music - a bibliography of musical settings of the poems and prose of William Blake. Berkeley, Los Angeles and Oxford: Berkeley, Los Angeles and Oxford: University of California Press. ISBN 0520097343.

- Gilchrist, Alexander; William Blake; Anne Gilchrist; D. G. Rossetti, eds. (1880). Life of William Blake. 2 (2nd ed.). London: MacMillan & Co.

- Gleckner, Robert F. (Sep 1961). "William Blake and the Human Abstract". PMLA. 76 (4): 373–379. doi:10.2307/460620. JSTOR 460620.

- Keynes, Geoffrey, ed. (1967). Blake Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192810898.

- Sampson, John (ed.). The poetical works of William Blake. Clarendon Press Oxford 1905. p. 134.

- Swinburne, A. C.. William Blake, a critical essay (Chapter: Lyrical poems), 1868.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Songs of Experience - The Human Abstract. |