The Experienced English Housekeeper

The Experienced English Housekeeper,[lower-alpha 1] is a cookery book by the English businesswoman Elizabeth Raffald (1733–1781). It was first published in 1769, and went through 13 authorised editions and at least 23 pirated ones.[1]

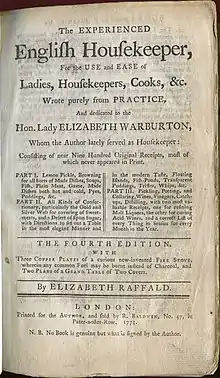

Title page, 1775 edition | |

| Author | Elizabeth Raffald |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Subject | English cooking |

| Genre | Cookery |

| Publisher | Elizabeth Raffald Sold by R. Baldwin |

Publication date | 1769 |

| Pages | 397 |

The book contains some 900 recipes for: soups; main dishes including roast and boiled meats, boiled puddings, and fish; desserts, table decorations and "little savory dishes"; potted meats, drinks, wines, pickles, preserves and distilled essences. The recipes consist largely of direct instructions to the cook, and do not contain lists of ingredients. The book is illustrated with three fold-out copper plate engravings.

The book is noted for its practicality, departing from earlier practice in avoiding plagiarism, consisting instead almost entirely of direct instructions based on Raffald's experience. It introduced the first known recipe for a wedding cake covered in marzipan and royal icing, and is an early use of barbecue. The book remains a reference for cookery writers.

Context

Raffald was born in Doncaster in 1733. Between 1748 and 1763 she was employed as a housekeeper by several families, including the Warburtons of Arley Hall in Cheshire, where she met her future husband, John Rafford, Arley Hall's head gardener. In 1763 the couple moved to Manchester, where Elizabeth opened a confectionery shop and John sold flowers and seeds at a market stall. They had 16 children, all girls.[2] As well as her cookery book, she wrote a book on midwifery and ran a register office in Manchester to place domestic servants with prospective employers. In 1773, she sold the copyright to the book to her publisher for £1400, equivalent to about £179,000 as of 2020.[1][2]

Raffald writes in her Preface that she not only worked as a housekeeper "in great and worthy families", but "had the opportunity of travelling with them".[3] The bibliographer William Carew Hazlitt observes that in this way she "widened her sphere of observation".[4] A 2005 article in Gastronomica described Raffald as "the most celebrated English cookery writer of the eighteenth century after Hannah Glasse".[5]

Book

Contents

The following page numbers refer to the 4th edition of 1775.

Part I [Soups, meat, fish, pies and puddings]

- Chapter 1: Soups. Page 1

- Chapter 2: Dressing Fish. Page 14

- Chapter 3: Roasting and Boiling. Page 52

- Chapter 4: Made Dishes. Page 79

- Chapter 5: Pies. Page 143

- Chapter 6: Puddings. Page 167

Part II [Desserts and accompanying dishes]

- Chapter 7: Making Decorations for a Table. Page 186

- Chapter 8: Preserving. Page 209

- Chapter 9: Drying and Candying. Page 237

- Chapter 10: Creams, Custards, and Cheese-Cakes. Page 247

- Chapter 11: Cakes. Page 264

- Chapter 12: Little Savory Dishes. Page 280

Part III [Preserves, pickles, wines, distilled essences]

- Chapter 13: Potting and Collaring. Page 293

- Chapter 14: Possets, Gruel, &c. Page 308

- Chapter 15: Wines, Catchup, and Vinegar. Page 317

- Chapter 16: Pickling. Page 342

- Chapter 17: Keeping Garden-Stuff, and Fruit. Page 358

- Chapter 18: Distilling. Page 364

[Appendices]

- A correct List of every Thing in Season in every Month of the Year. Page 368

- Directions for a Grand Table. Page 381

- Index. Page 383 [Finis Page 397]

Approach

The book begins without a table of contents, though the three parts are described on the title page. The front matter consists of a dedication "To the Honourable Lady Elizabeth Warburton", occupying two pages, a three-page Preface to the First Edition, and a fold-out plate of a suitable stove, complete with a "Description of the Plate" on the facing page. Plagiarism was combated in later editions (from as early as 1775) with the declaration at the foot of the title page "N. B. No Book is genuine but what is signed by the Author", and a matching handwritten signature in brownish-black ink bracketing the heading of Chapter 1.

Each chapter begins with a section of "Observations" on the topic of the chapter; thus, Chapter 3 has three pages of "Observations on Roasting and Boiling". The observations are close to instructions, as "when you boil mutton or beef, observe to dredge them well with flour before you put them into the kettle of cold water, keep it covered, and take off the scum".[6]

The rest of each chapter consists entirely of "receipts" (recipes). These are usually named as instructions like "To roast a Pig", "To make Sauce for a Pig". Occasionally there is a comment, as in "A nice way to dress a Cold Fowl".

The names of dishes are overwhelmingly in English, even when the dish is in fact foreign; thus "To make Cream Cakes" is the heading for the recipe for meringue, beginning "Beat the whites of nine eggs to a stiff froth, then stir it gently with a spoon, for fear the froth should fall".[7]

Raffald is however not afraid to use foreign words for new techniques, as "to fricassee Lamb Stones",[8] "to barbecue a Pig",[9] "Bouillie Beef",[10] "Ducks a-la-mode",[11] "To fricando Pigeons",[12][lower-alpha 2] "To ragoo Mushrooms".[13][lower-alpha 3] In explanation of this, she writes in the Preface to the First Edition:

And though I have given some of my dishes French names, as they are known only by those names, yet they will not be found very expensive, nor add compositions but as plain as the nature of the dish will admit of.[3]

The recipes themselves are written entirely as directions, without lists of ingredients. They are generally terse, the reader being assumed to know how to beat eggs and to separate the white from the yolk, to boil starchy foods in milk without burning the pan, or to make a "paste" (pastry), all of which are required skills for this recipe for sago pudding:[lower-alpha 4]

A SAGO PUDDING another way. Boil two ounces of sago till it is quite thick in milk, beat six eggs, leaving out three of the whites, put to it half a pint of cream, two spoonfuls of sack, nutmeg and sugar to your taste; put a paste round your dish.[15]

Illustrations

Official editions contained three engravings on pages that folded out, interspersed with the text. The first illustrated a stove; the other two, suggested table layouts for the first course and for the second course. Raffald explains in her Directions for a GRAND TABLE that:

being desirous of rendering it easy for the future, have made it my study to set out the dinner in as elegant a manner as lies in my power, and in the modern taste; but finding I could not express myself to be understood by young house-keepers, in placing the dishes upon the table, obliged me to have two copper-plates; as I am very unwilling to leave even the weakest capacity in the dark, it being my greatest study to render my whole work both plain and easy.[16]

The book, intended for "a burgeoning middle class that required explanation and elucidation", provided an accurate description of how to serve an elegant meal à la française, complete with two fold-out engravings of the layout of a table with 25 "prettily-shaped" and symmetrically-arranged serving-dishes "laid in generous profusion on the table", each annotated with the name of the appropriate recipe. It is not clear whether the term "cover" for the layout of such a "Grand meal" is an acknowledgement of the French couvert, as it may simply mean, with Hannah Glasse, "a large table to cover".[17]

The layout for the second course contains the dishes (from top):

Snow balls, Crawfish in savory jelly, Moonshine,

Fish pond, Mince Pies, Globes of gold web with mottoes in them,

Stewed Cardoon, Pompadore Cream,

Roast Woodcocks, transparent pudding covered with a silver web, pea Chick with asparagus,

Pistacha Cream, Crocrant with Hot Pippins, Floating Island,

Collared Pig, Pott'd Lampreys,

Rocky Island, Snipes in savory jelly, Burnt Cream,

Roast'd Hare.

Influence

Contemporary

The Monthly Review, Or, Literary Journal of 1770 listed the book, commenting only that "The Reviewers[lower-alpha 5] are sorry to own, but their regard to truth obliges them to it, that there are subjects with which, alas! they are too little acquainted, to pretend to be judges of what the learned may publish concerning them."[18]

The Experienced English Housekeeper was "extremely successful", going through 13 authorised editions and at least 23 pirated ones.[1] To attempt to reduce the piracy, Raffald signed each copy on the first page of the main text in ink, and printed the message "N.B. No Book is genuine but what is signed by the Author" on the title page. Finally in 1773, she sold the copyright to her publisher for £1400,[2] equivalent to about £179,000 in 2020.

As well as direct piracy, the book inspired other "experienced housekeepers" to try to profit by publishing books of culinary advice. In 1795, Sarah Martin published The New Experienced English Housekeeper, for the Use and Ease of Ladies' Housekeepers, Cooks, &c. written purely for her own practice.[19] Similarly, Susanna Carter entitled her 1822 book The Experienced Cook and Housekeeper's Guide. It included 12 engravings "for the arrangement of dinners of two courses".[20]

As an illustration of how familiar Raffald had made the idea of the experienced English housekeeper, The Critical Review, Or, Annals of Literature of 1812 wrote that "The arranging of a dinner-table is attended in Iceland with little trouble, and would afford on scope for the display of the elegant abilities of an experienced English housekeeper. On the cloth was nothing but a plate, a knife and fork, a wine glass, and a bottle of claret, for each guest, except that in the middle stood a large and handsome glass-castor of sugar, with a magnificent silver top."[21]

Firsts

The Experienced English Housekeeper was the first book to contain a recipe for what became the classic wedding cake complete with marzipan and royal icing.[5]

The Oxford English Dictionary of 1888[22] credited Raffald as one of the earliest sources in English to mention barbecue in cookery.[23]

On modern cookery

The Cambridge Guide to Women's Writing in English noted in 1999 that Raffald distinguishes her work as purely from practice, unlike books of untried recipes copied from elsewhere, and that she apologises for "the plainness of the style" in her introductory letter. The Guide observes, however, that "this is the essence of her lasting appeal, and her clarity and economy with words find an echo in the work of Eliza Acton a century later."[24]

The cookery writer Sophie Grigson wrote in The Independent that her mother Jane made Raffald's Orange Custards "every year when the Seville orange season was in full swing, a treat to look forward to."[25]

In 2013, Raffald's former workplace, Arley Hall, brought some of her recipes including lamb pie, pea soup and rice pudding back to their tables. The general manager Steve Hamilton however said they would avoid Raffald's turtle and calf's foot pudding.[1]

Publication

Raffald states in her Preface that she personally "perused [every sheet] as it came from the press, having an opportunity of having it printed by a neighbour, whom I can rely on". She writes that "The whole work being now compleated to my wishes", she must thank her friends and subscribers; she states that over 800 of them contributed, "raising me so large a subscription, which far excells my expectations".[26] She was thus a self-publisher.

Official

The official editions were largely published in London, with minor differences.

- 1st Edition, 1769. Manchester: J Harrop.

- 2nd Edition, 1771. London: R. Baldwin.[lower-alpha 6]

- 3rd Edition, 1773. London: R. Baldwin.

- 4th Edition, 1775. London: R. Baldwin.

- 5th Edition, 1776. London: R. Baldwin.

- 6th Edition, 1778. London: R. Baldwin.

- 7th Edition, 1780. London: R. Baldwin.[lower-alpha 7]

- 8th Edition, 1782. London: R. Baldwin.[lower-alpha 8]

- 9th Edition, 1784. London: R. Baldwin.

- 10th Edition, 1786. London: R. Baldwin.

- 11th Edition, 1794. London: R. Baldwin.

- 12th Edition, 1799. London: R. Baldwin.

- New Edition, 1801. London: R. Baldwin.

- 13th Edition, 1806. London: R. Baldwin.

Other editions

Many unofficial editions were produced in Britain and America, including:

- London: A. Millar, W. Law & R. Cater, 1787.

- London: A. Millar, W. Law & R. Cater, 1789.[lower-alpha 9]

- London: A. Millar, W. Law & R. Cater, 1791.

- London: W. Osborne & T. Griffin, 1794.

- London: W. Osborne & T. Griffin, 1798.

- Manchester: G. Bancks, 1798.

- London: Brambles, Meggitt and Waters, 1803.

- York: T. Wilson & R. Spence, 1803.

- London: Brambles, Meggitt and Waters, 1805.

- London: R. & W. Dean, 1807.

- London: Brambles, Meggitt and Waters, 1808.

- London: T. Wilson & R. Spence, 1806.

- London: T. Wilson & R. Spence, 1808.

- London: Brambles, Meggitt and Waters, 1814.

- Philadelphia: James Webster, 1818.

Notes

- The book's full title is The Experienced English Housekeeper, For the Use and Ease of Ladies, Housekeepers, Cooks, &c. Wrote purely from Practice, and dedicated to the Hon. Lady Elizabeth Warburton, Whom the Author lately served as Housekeeper: Consisting of near Nine Hundred Original Receipts, most of which never appeared in Print.

- Fricandó is a traditional Catalan dish.

- Ragout is a French dish.

- Sago was introduced to Europe around 1300.[14]

- Presumably male.

- 3 foldouts (stove, 2 table layouts).

- Reissued in paperback by Gale Ecco, 2010. ISBN 978-1-170-98115-3.

- First to feature frontispiece of Mrs Raffald (after her death).

- 3 foldouts.

References

- "Georgian chef Elizabeth Raffald's recipes return to Arley Hall menu". BBC. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- Local History Library of the Manchester Central Library (1978). Men and Women of Manchester. William Morris Press. pp. 5–6.

- Raffald, 1775. Page ii

- Hazlitt, William Carew (1886). Old Cookery Books and Ancient Cuisine. London: Elliot Stock. p. 177. OCLC 1746766.

- Wilson, Carol (2005). Wedding Cake: A Slice of History. Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture. 5. pp. 69–72. doi:10.1525/gfc.2005.5.2.69. JSTOR 10.1525/gfc.2005.5.2.69.

- Raffald, 1775. Page 53

- Raffald, 1775. Page 272

- Raffald, 1775. Page 110

- Raffald, 1775. Page 111

- Raffald, 1775. Page 113

- Raffald, 1775. Page 129

- Raffald, 1775. Page 132

- Raffald, 1775. Page 288

- Rumble, Victoria R. (7 April 2009). Soup Through the Ages: A Culinary History with Period Recipes. McFarland. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7864-5390-0.

- Raffald, 1775. Page 177

- Raffald, 1775. Pages 381–382

- Walker, Harlan (2002). The Meal: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, 2001. Oxford Symposium. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-1-903018-24-8.

- Griffiths, Ralph; Griffiths, G. E. (1770). The Monthly Review, Or, Literary Journal. p. 331.

- The British Critic and Quarterly Theological Review. F. and C. Rivington. 1796. p. 95.

- Carter, Susanna (1822). The Experienced Cook and Housekeeper's Guide. London: W. S. Johnson.

- The Critical Review: Or, Annals of Literature. 1812. p. 25.

- "Oxford English Dictionary, 1888". Archive.org. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- "Elizabeth Raffald – The Experienced English Housekeeper". The Arden Arms, Stockport. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Sage, Lorna; Greer, Germaine; Showalter, Elaine (30 September 1999). The Cambridge Guide to Women's Writing in English. Cambridge University Press. p. 519. ISBN 978-0-521-66813-2.

- Grigson, Sophie (6 February 1993). "Food and Drink: Marmalade is not the only fruit of oranges: Sophie Grigson, in her first column, suggests new ways of capturing the sweetness and sharpness of winter Sevilles". The Independent. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Raffald, 1775. Pages i–ii

External links

- The Experienced English Housekeeper at Archive.org

- Experienced English Housekeeper as a set of 23 audio podcasts on iTunes

- Seven different editions (Online Books, University of Pennsylvania)

The Experienced English Housekeeper public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Experienced English Housekeeper public domain audiobook at LibriVox