The Days of the Turbins

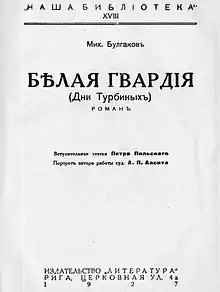

The Days of the Turbins (Russian: Дни Турбиных, romanized: Dni Turbinykh) is a four-act play by Mikhail Bulgakov based upon his novel The White Guard.

| The Days of the Turbins | |

|---|---|

Stanislavski's production of Mikhail Bulgakov's The Days of the Turbins (1926), with scenic design by Nikolai Ulyanov.[1] | |

| Written by | Mikhail Bulgakov |

| Date premiered | 5 October 1926 |

| Place premiered | Moscow Art Theatre |

| Original language | Russian |

| Subject | Russian 1918-1920 Civil War |

| Genre | Realistic drama |

| Setting | Kiev, 1919 |

It was written in 1925 and premiered on 5 October 1926 in Moscow Art Theatre (MAT), directed by Konstantin Stanislavsky. In April 1929 the production was cancelled as a result of severe criticism in the Soviet press. On 16 February 1932, resulting from the direct interference of Joseph Stalin, it was re-started and continued until June 1941, to considerable public acclaim. It ran for 987 performances in the course of these ten years.

There are three versions of the play's text. The first was written in July-September 1925. The title The Days of the Turbins was also used for the novel itself, the latter's Paris (1927, 1929, Concorde) edition was titled The Days of the Turbins (The White Guard). The play's second version (never published in Russian) was translated into German and first came out in Munich in 1934. The third version of the text was published in Moscow in 1955, supervised personally by Elena Sergeyevna Bulgakova.[2]

Background

When the Moscow Art Theatre approached Bulgakov in 1925, suggesting that he should write a play for them to stage, the author has been toying with the same idea for some time. In 1920, while in Vladikavkaz, he'd written a play called The Turbin Brothers, which was set during the times of the 1905 Revolution, and since then has been thinking of coming up with some kind of sequel.

As well as the novel The White Guard, which served as a blueprint for it, the play was based upon its author's personal experience in Kiev of late 1919 and early 1920, when, at the height of the Russian Civil War, the city succumbed to anarchy and violence.

As the novel before it, the play had a strong autobiographical aspect to it. The description of the house of the Turbins corresponds to that of the house of the Bulgakov family in Kiev, now the Mikhail Bulgakov Museum.

Bulgakov's maternal grandmother Anfisa Ivanovna, in marriage Pokrovskaya, was born Turbina, hence the name of the family. The character of Alexey Turbin could be seen as a self-portrait. Nikolka Turbin bears strong resemblance to the author's brother, Nikolai Bulgakov. The real person behind Elena Talberg-Turbina was Bulgakov's sister Varvara Afanasyevna.[3] The prototype for the cynical careerist Colonel Talberg was Varvara's husband Leonid Sergeyevich Karum (1888–1968), who first served under Hetman Skoropadsky, then joined Anton Denikin's army and ended up as an instructor in a Red Army military school. Such an interpretation of his character caused a family row and a rift between Bulgakov and the Karums.

The character of Myshlayevsky apparently had no immediate real-life prototype (although some sources point at Nikolai Syngayevsky, the author's friend from the years of childhood)[3] but by way of bizarre coincidence it 'found' itself one, in retrospect. During the 1926/1927 season the MAT offices received a letter addressed to Bulgakov, signed "Viktor Viktorovich Myshalyevsky". In the introduction, its author implied that Bulgakov had known him personally and 'expressed interest' in his life story. The letter told the story of a former White Army officer who had joined the Red Army, initially even with some enthusiasm, only to become totally disillusioned with the Bolshevik regime and the new Soviet reality.[2]

History

On 3 April 1925, the Moscow Art Theatre's Second Studio co-director (and later a respected Soviet reader in drama) Boris Vershilov invited Bulgakov to visit him at the theatre and suggested that the latter should write a play based upon The White Guard. Bulgakov set upon working on it in July and finished the first draft in September. That month he recited it for the audience of the theatre's actors and officials, which included Stanislavski. Its first version, closely following the novel's plotline, featured the characters Malyshev and Nai-Turs; Alexey Turbin in it was still an army doctor.

Stanislavski found the original plotline overdrawn and laden with too many characters, some of them indistinguishable from some of the others. In the second draft there was no Nai-Turs, whose lines were given to Colonel Malyshev. By the January 1926 final casting, Malyshev was too, and Alexey Turbin became the artillery colonel, as well a kind of proponent for the ideology of the White movement.[2]

The next change was prompted by censors: the scene at the (Ukrainian nationalist leader) Symon Petliura's headquarters had to be removed because the atmosphere of anarchic violence there, apparently, resonated too strong with many people's reminiscences of the Civil War realities, relating to the atrocities committed by the Red Army.

The title "The White Guard" also caused problems. Stanislavski, trying to appease the Repertoire Committee (Glavrepertkom) suggested that it should be called "Before the End" (Перед концом) which Bulgakov vehemently protested against. In August 1926 they finally agreed on The Days of the Turbins. On 25 September 1926 the play received the permission to be produced on stage, for the MAT exclusively, provided that the revolutionary hymn "The Internationale" should be played, crescendo, in the finale. Also, several new lines were given to Myshlayevsky, to indicate that he, bitterly disillusioned, as he was, with the White movement, was now ready to join the Red Army.[2]

The Days of the Turbins, directed by Stanislavsky, premiered on 5 October 1926. The first Soviet play portraying the White Army officers realistically, as not caricature villains, but likeable people, caused furore. In its first season, in 1926/1927 The Days of the Turbins ran for 108 performance, which was a record figure that year for Moscow theatres. Despite numerous attempts at obstructions, it became a huge a hit, especially with the non-party public. The Soviet press panned it, though, and as the time went by, the severity of the criticism increased. In April 1929 the MAT leadership succumbed to the pressure and the production was cancelled.[2]

On 28 March 1930 Bulgakov sent a letter to the Soviet government, protesting against the treatment that the play had been subjected to in the Soviet press, mentioning 298 clips of the negative reviews he'd collected. He insisted that his aim was "to portray the intelligentsia, our country's finest social strata. In particular, to show, in the War and Peace tradition, one single family of intelligentsia, belonging to the dvoryanstvo, which, by the will of history itself had been thrown into the White Guard camp. Such [artistic move] is natural for a writer who himself comes from the intelligentsia." His letter remained unanswered, but on 18 April, soon after Vladimir Mayakovsky's suicide, Bulgakov received a telephone call from Stalin who promised support and asked the author not to think of leaving the USSR.[2][4]

Bulgakov sent Stalin some more letters; they remained unanswered, but on 16 February 1932, unexpectedly, the production of the Days of the Turbins was revived and the play re-entered the Moscow Art Theatre major repertoire. For Bulgakov this came as a surprise. "For reasons unknown to me, which I am not in a position to speculate upon, the Soviet government issued an extraordinary order for the MAT to re-start the production of The Days of the Turbins. For the author of that play this means only one thing: the huge bulk of his life has been risen from the dead, simple as that," Bulgakov wrote to his friend, the literary and philosophy historian Pavel Popov (1892-1964).[5]

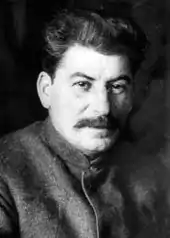

It was obvious for both that this 'extraordinary' order could not have been issued by any one other that Stalin himself. Later it was revealed that the Soviet leader had seen the play at least fifteen times in the course of three years, often visiting the theatre incognito. Apparently, Stalin came to such a decision spontaneously, upon having returned from the Moscow Art Theatre disgusted with what he called 'a bad play', Alexander Afinogenov's Fear (tellingly, criticising the idea that the old intelligntsia should be integrated into the new Soviet society and, at that, quite popular with the party-controlled media), and impulsively decided that the 'good one', The Days of the Turbins, should be restored. His orders were promptly heeded.[5]

Stalin himself tried to downplay his own infatuation with the Days of the Turbins and its MAT production. In a letter to Vladimir Bill-Belotserkovski dated 2 February 1929, he argued: "...The play does more good than harm. Mind you, the general impression which the viewer leaves the theatre with, is that of the Bolsheviks' victory. "That the likes of the Turbins decide to lay down the arms and succumb to the will of the people, conceding the defeat, could mean only one thing: that the Bolsheviks are invincible."[6] Such a line of argument served as red herring for Stalin, the critic Marianna Shaternikova argued, for "there was nothing in the play which might have been interpreted even as a hint at the Bolshevism's invincibility. What there was instead is the all-pervading sense of total betrayal... as the White Army generals, the Hetman, the Germans and all those whom they considered friends or allies, abandoning [the Turbins]." A small detail found in the diaries of Elena Bulgakova shows how deeply moved the Soviet leader had been by the play. "You perform Alexey so good! Your Turbin's small mustachios even visit me in my dreams, I cannot forget them," he told the MAT actor Nikolai Khmelyov.[5]

Major characters

- Alexey Vasilyevich Turbin, the artillery colonel, 30

- Nikolai Turbin, his brother, 18

- Elena Vasilyena Talberg, their sister, 24

- Vladimir Robertovich Talberg, the White Army HQ colonel, her husband, 38

- Viktor Viktorovich Myshlayevsky, artillery captain, 38

- Leonid Yuryevich Shervinsky, poruchik, Hetman's adjutant,

- Alexander Bronislavovich Studzinsky, captain, 29

- Lariosik, Alexey's cousin from Zhytomyr, 21

- Pavlo Skoropadskyi, Hetman of Ukraine

- Bolbotun, Symon Petliura's First Cavalry Division commander[7]

- Galanba, Uragan, Kirpaty, the Petliura's army's soldiers

- Von Schratt, German general, Von Doust, German army major.

Summary

Kiev of the late 1918 — early 1919 is in chaos; first Hetman Pavlo Skoropadskyi's regime falls, to be succeeded by the Directorate of Ukraine, then Symon Petliura comes in, only to be ousted from the city by the Bolsheviks. The family of the Turbins are caught in this turmoil, suffering their own tragedies, watching their whole world crash, amidst mindless violence, feeling abandoned and betrayed. Colonel Alexey Turbin and his brother Nikolai remain loyal to the White Movement and are determined to give their lives for it. Elena's husband Colonel Talberg flees the city with the German troops. Amidst horrors and uncertainty the family gathers to celebrate the New Year's Day.

Publication history

The Days of the Turbins was published for the first time in Russian in 1955, in Moscow, under Elena Bulgakova's personal supervision. Before that, in 1934, in Boston and New York City, it came out in English, translated by Y. Lyons and F. Bloch, respectively. Earlier, in 1927, its second version was translated into German by K. Rosenberg.

Production history

The Days of the Turbins' premiered on 5 October 1926 in Moscow Art Theatre, directed by Konstantin Stanislavsky, co-directed by Ilya Sudakov (1890-1969).[8] The cast included Nikolai Khmelyov as Alexey Turbin, Ivan Kudryavtsev as Nikolka, Vera Sokolova as Elena, Mark Prudkin as Shervinsky (his song has been performed for several years by the Bolshoi opera singer Pyotr Selivanov), Evgeny Kaluzhsky as Studzinsky, Boris Dobronravov as Myshlayevsky, Vsevolod Verbitsky as Talberg, Mikhail Yanshin as Lariosik, Viktor Stanitsyn as Von Shratt, Robert Schilling as Von Dust, Vladimir Ershov as Getman, Nikolai Titushin as the deserter, Alexander Anders as Bolbotun, Mikhail Kedrov as Maxim.

The Days of the Turbins enjoyed enormous success. Bulgakov's secretary I.S. Raaben (who'd typed the novel The White Guard and who was invited to the theatre by Bulgakov personally), remembered: "That was astounding. All these things were still very much alive in the people's memories. There were fits of hysteria, people fainted, seven people were driven away by ambulance, for there were lots of people in the audience who'd come through the Petlyura horrors, and all those Civil War hardships."[2]

The publicist Ivan Solonevich remembered an episode, with the White Army officers on stage after having drunk some vodka, were supposed sing the anthem "God Save the Tsar!" in a ramshackle, disheartened manner. "Then something inexplicable happened. The whole audience started to rise to their feet. The actors' voices strengthened. People were standing and silently weeping. Next to me, an old worker, my Party chief, rose up too. He later tried helplessly to rationalize what had happened. I helped him by saying that was mass hypnosis. But that was something much more than that... The directors received the orders to stage the episode in such a way so as to make it look derogatory, and the rendition insulting for the old Russia's hymn. For some reason they failed to do so and that proved to be the reason why the production was finally cancelled."[9]

In April 1929 the production was cancelled. On 16 February 1932, due to the direct interference of Joseph Stalin, it was revived, and continued to run until June 1941. The Days of the Turbins had 987 runs in the course of these ten years.[2]

Critical response

Throughout its first three years in the Moscow Art Theatre the play was severely criticised in the Soviet press, with numerous celebrities like Vladimir Mayakovsky, joining the chorus of detractors. The minister of education Anatoly Lunacharsky (writing for Izvestia on 8 October 1926) insisted that the play amounted to the apology of belogvardeyshchina. Later in 1933 he called it "the drama of a restricted, sly even, capitulation". Novy Zritel (Modern Viewer, on 2 February, 1927) described is as the "cynical attempt to idealize the White Army".[2]

What seemed to enrage the critics most was the fact that the White Army officers in the play were portrayed almost as Chekhov-type characters. The future Glavrepertkom chief O. Litkovsky (1892-1971) called the play "the Cherry Orchard of the White movement" and asked rhetorically: "The sufferings of the landowner Ranevskaya, who is about to have her cherry orchard ruthlessly axed, what bearings do they have for the Soviet theatre-goers? And should we care for the nostalgia suffered by immigrants, either external or internal, for the White movement, so timelessly deceased?"[2]

The only review that could be said to be positive was that of N. Rukavishnikov in Komsomolskaya Pravda who, replying to the poet Alexander Bezymensky who called Bulgakov 'the neo-bourgeous scum', argued that "now, as we are approaching the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution... it is quite safe to portray [the 'white' officers] in a more realistic manner" and that "the viewer has had enough of the agitprop-spawned hairy priests and fat capitalists in bowler hats."

Bulgakov's play's secret admirer, though, proved to be Joseph Stalin, who admittedly watched the play in MAT at least fifteen times and invariably spoke of it in rapturous terms, according to Valery Shanayev who also mentioned that there were several Bulgakov's books in the Soviet leader's Kremlin library. It was due to Stalin's personal orders that the play was re-installed and soon became part of what was known as the MAT's major repertoire.[2]

Modern critics consider the play the peak of Bulgakov's development as a playwright and a 20th-century drama classic.[10]

References

- Николай Павлович Ульянов. Biography at the Moscow Art Theatre site. - Станиславский искал нового сближения с Ульяновым [...] уговорив взяться за “Дни Турбиных”. Художник не очень ценил эту свою работу из-за ее “живописной скупости”. Зато ее оценили и актеры, и публика...

- Commentaries to Дни Турбиных at the Russian Bulgakov site.

- The White Guard at the Bulgakov On-line Encyclopedia

- This resulted in Bulgakov's finally joining the MAT stuff and spending the last years of his life in a kind of 'internal exile', increasingly frustrated and now unable to go abroad, to visit his brother Nikolai who lived in Paris.

- Shaternikova, Marianna. Why Did Stalin Loved The Days of the Turbuns. Почему Сталин любил спектакль «Дни Турбиных». Опубликовано: 15 октября 2006 г.

- Сталин И. В. Сочинения. Ответ Билль-Белоцерковскому Archived 2012-05-13 at the Wayback Machine. — Т. 11. — М.: ОГИЗ; Государственное издательство политической литературы, 1949. С. 326—329

- The real historical figure behind it was Pyotr Bolbochan

- Mikhail Bulgakov at the Moscow Art Theatre

- Solonevich, Ivan. Solving the Mystery of Russia // Солоневич И. Л. Загадка и разгадка России. М.: Издательство «ФондИВ», 2008. С.451

- Schwartz, Anatoly. Thinking of Bulgakov. Анатолий Шварц. «Думая о Булгакове». Журнал «Слово\Word» 2008, № 57.