Tabu search

Tabu search, created by Fred W. Glover in 1986[1] and formalized in 1989,[2][3] is a metaheuristic search method employing local search methods used for mathematical optimization.

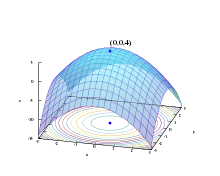

Local (neighborhood) searches take a potential solution to a problem and check its immediate neighbors (that is, solutions that are similar except for very few minor details) in the hope of finding an improved solution. Local search methods have a tendency to become stuck in suboptimal regions or on plateaus where many solutions are equally fit.

Tabu search enhances the performance of local search by relaxing its basic rule. First, at each step worsening moves can be accepted if no improving move is available (like when the search is stuck at a strict local minimum). In addition, prohibitions (henceforth the term tabu) are introduced to discourage the search from coming back to previously-visited solutions.

The implementation of tabu search uses memory structures that describe the visited solutions or user-provided sets of rules.[2] If a potential solution has been previously visited within a certain short-term period or if it has violated a rule, it is marked as "tabu" (forbidden) so that the algorithm does not consider that possibility repeatedly.

Background

The word tabu comes from the Tongan word to indicate things that cannot be touched because they are sacred.[4]

Tabu search (TS) is a metaheuristic algorithm that can be used for solving combinatorial optimization problems (problems where an optimal ordering and selection of options is desired).

Current applications of TS span the areas of resource planning, telecommunications, VLSI design, financial analysis, scheduling, space planning, energy distribution, molecular engineering, logistics, pattern classification, flexible manufacturing, waste management, mineral exploration, biomedical analysis, environmental conservation and scores of others. In recent years, journals in a wide variety of fields have published tutorial articles and computational studies documenting successes by tabu search in extending the frontier of problems that can be handled effectively — yielding solutions whose quality often significantly surpasses that obtained by methods previously applied. A comprehensive list of applications, including summary descriptions of gains achieved from practical implementations, can be found in [5] Recent TS developments and applications can also be found in Tabu Search Vignettes.

Basic description

Tabu search uses a local or neighborhood search procedure to iteratively move from one potential solution to an improved solution in the neighborhood of , until some stopping criterion has been satisfied (generally, an attempt limit or a score threshold). Local search procedures often become stuck in poor-scoring areas or areas where scores plateau. In order to avoid these pitfalls and explore regions of the search space that would be left unexplored by other local search procedures, tabu search carefully explores the neighborhood of each solution as the search progresses. The solutions admitted to the new neighborhood, , are determined through the use of memory structures. Using these memory structures, the search progresses by iteratively moving from the current solution to an improved solution in .

Tabu Search has several similarities with Simulated annealing, as both involve possible down hills moves. In fact, Simulated annealing could be viewed as a special form of TS, where by we use "graduated tenure", that is, a move becomes tabu with a specified probability.

These memory structures form what is known as the tabu list, a set of rules and banned solutions used to filter which solutions will be admitted to the neighborhood to be explored by the search. In its simplest form, a tabu list is a short-term set of the solutions that have been visited in the recent past (less than iterations ago, where is the number of previous solutions to be stored — is also called the tabu tenure). More commonly, a tabu list consists of solutions that have changed by the process of moving from one solution to another. It is convenient, for ease of description, to understand a “solution” to be coded and represented by such attributes.

Types of memory

The memory structures used in tabu search can roughly be divided into three categories:[6]

- Short-term: The list of solutions recently considered. If a potential solution appears on the tabu list, it cannot be revisited until it reaches an expiration point.

- Intermediate-term: Intensification rules intended to bias the search towards promising areas of the search space.

- Long-term: Diversification rules that drive the search into new regions (i.e. regarding resets when the search becomes stuck in a plateau or a suboptimal dead-end).

Short-term, intermediate-term and long-term memories can overlap in practice. Within these categories, memory can further be differentiated by measures such as frequency and impact of changes made. One example of an intermediate-term memory structure is one that prohibits or encourages solutions that contain certain attributes (e.g., solutions which include undesirable or desirable values for certain variables) or a memory structure that prevents or induces certain moves (e.g. based on frequency memory applied to solutions sharing features in common with unattractive or attractive solutions found in the past). In short-term memory, selected attributes in solutions recently visited are labeled "tabu-active." Solutions that contain tabu-active elements are banned. Aspiration criteria are employed that override a solution's tabu state, thereby including the otherwise-excluded solution in the allowed set (provided the solution is “good enough” according to a measure of quality or diversity). A simple and commonly used aspiration criterion is to allow solutions which are better than the currently-known best solution.

Short-term memory alone may be enough to achieve solutions superior to those found by conventional local search methods, but intermediate and long-term structures are often necessary for solving harder problems.[7] Tabu search is often benchmarked against other metaheuristic methods — such as Simulated annealing, genetic algorithms, Ant colony optimization algorithms, Reactive search optimization, Guided Local Search, or greedy randomized adaptive search. In addition, tabu search is sometimes combined with other metaheuristics to create hybrid methods. The most common tabu search hybrid arises by joining TS with Scatter Search,[8][9] a class of population-based procedures which has roots in common with tabu search, and is often employed in solving large non-linear optimization problems.

Pseudocode

The following pseudocode presents a simplified version of the tabu search algorithm as described above. This implementation has a rudimentary short-term memory, but contains no intermediate or long-term memory structures. The term "fitness" refers to an evaluation of the candidate solution, as embodied in an objective function for mathematical optimization.

sBest ← s0

bestCandidate ← s0

tabuList ← []

tabuList.push(s0)

while (not stoppingCondition())

sNeighborhood ← getNeighbors(bestCandidate)

bestCandidate ← sNeighborhood[0]

for (sCandidate in sNeighborhood)

if ( (not tabuList.contains(sCandidate)) and (fitness(sCandidate) > fitness(bestCandidate)) )

bestCandidate ← sCandidate

end

end

if (fitness(bestCandidate) > fitness(sBest))

sBest ← bestCandidate

end

tabuList.push(bestCandidate)

if (tabuList.size > maxTabuSize)

tabuList.removeFirst()

end

end

return sBest

Lines 1-4 represent some initial setup, respectively creating an initial solution (possibly chosen at random), setting that initial solution as the best seen to date, and initializing a tabu list with this initial solution. In this example, the tabu list is simply a short term memory structure that will contain a record of the elements of the states visited.

The core algorithmic loop starts in line 5. This loop will continue searching for an optimal solution until a user-specified stopping condition is met (two examples of such conditions are a simple time limit or a threshold on the fitness score). The neighboring solutions are checked for tabu elements in line 9. Additionally, the algorithm keeps track of the best solution in the neighbourhood, that is not tabu.

The fitness function is generally a mathematical function, which returns a score or the aspiration criteria are satisfied — for example, an aspiration criterion could be considered as a new search space is found[4]). If the best local candidate has a higher fitness value than the current best (line 13), it is set as the new best (line 14). The local best candidate is always added to the tabu list (line 16) and if the tabu list is full (line 17), some elements will be allowed to expire (line 18). Generally, elements expire from the list in the same order they are added. The procedure will select the best local candidate (although it has worse fitness than the sBest) in order to escape the local optimal.

This process continues until the user specified stopping criterion is met, at which point, the best solution seen during the search process is returned (line 21).

Example: the traveling salesman problem

The traveling salesman problem (TSP) is sometimes used to show the functionality of tabu search.[7] This problem poses a straightforward question — given a list of cities, what is the shortest route that visits every city? For example, if city A and city B are next to each other, while city C is farther away, the total distance traveled will be shorter if cities A and B are visited one after the other before visiting city C. Since finding an optimal solution is NP-hard, heuristic-based approximation methods (such as local searches) are useful for devising close-to-optimal solutions. To obtain good TSP solutions, it is essential to exploit the graph structure. The value of exploiting problem structure is a recurring theme in metaheuristic methods, and tabu search is well-suited to this. A class of strategies associated with tabu search called ejection chain methods has made it possible to obtain high-quality TSP solutions efficiently [10]

On the other hand, a simple tabu search can be used to find a satisficing solution for the traveling salesman problem (that is, a solution that satisfies an adequacy criterion, although not with the high quality obtained by exploiting the graph structure). The search starts with an initial solution, which can be generated randomly or according to some sort of nearest neighbor algorithm. To create new solutions, the order that two cities are visited in a potential solution is swapped. The total traveling distance between all the cities is used to judge how ideal one solution is compared to another. To prevent cycles – i.e., repeatedly visiting a particular set of solutions – and to avoid becoming stuck in local optima, a solution is added to the tabu list if it is accepted into the solution neighborhood, .

New solutions are created until some stopping criterion, such as an arbitrary number of iterations, is met. Once the simple tabu search stops, it returns the best solution found during its execution.

References

- Fred Glover (1986). "Future Paths for Integer Programming and Links to Artificial Intelligence". Computers and Operations Research. 13 (5): 533–549. doi:10.1016/0305-0548(86)90048-1.

- Fred Glover (1989). "Tabu Search – Part 1". ORSA Journal on Computing. 1 (2): 190–206. doi:10.1287/ijoc.1.3.190.

- Fred Glover (1990). "Tabu Search – Part 2". ORSA Journal on Computing. 2 (1): 4–32. doi:10.1287/ijoc.2.1.4.

- "Courses" (PDF).

- F. Glover; M. Laguna (1997). Tabu Search. Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4613-7987-4.

- Fred Glover (1990). "Tabu Search: A Tutorial". Interfaces.

- M. Malek; M. Huruswamy; H. Owens; M. Pandya (1989). "Serial and parallel search techniques for the traveling salesman problem". Annals of OR: Linkages with Artificial Intelligence.

- F. Glover, M. Laguna & R. Marti (2000). "Fundamentals of Scatter Search and Path Relinking". Control and Cybernetics. 29 (3): 653–684.

- M. Laguna & R. Marti (2003). Scatter Search: Methodology and Implementations in C. Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 9781402073762.

- D. Gamboa, C. Rego & F. Glover (2005). "Data Structures and Ejection Chains for Solving Large Scale Traveling Salesman Problems". European Journal of Operational Research. 160 (1): 154–171. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.417.9789. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2004.04.023.