Symphony No. 5 (Mendelssohn)

The Symphony No. 5 in D major/D minor, Op. 107, known as the Reformation, was composed by Felix Mendelssohn in 1830 in honor of the 300th anniversary of the Presentation of the Augsburg Confession. The Confession is a key document of Lutheranism and its Presentation to Emperor Charles V in June 1530 was a momentous event of the Protestant Reformation. This symphony was written for a full orchestra and was Mendelssohn's second extended symphony. It was not published until 1868, 21 years after the composer's death – hence its numbering as '5'. Although the symphony is not very frequently performed, it is better known today than when it was originally published. Mendelssohn's sister, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, chose the name Reformation Symphony.[1]

| Symphony No. 5 | |

|---|---|

| Reformation | |

| by Felix Mendelssohn | |

Drawing of the composer by Eduard Bendemann, 1833 | |

| Key | D major/D minor |

| Catalogue | Op. 107 |

| Occasion | Tercentennial of the Augsburg Confession |

| Composed | 1830 |

| Performed | 1832 |

| Published | 1868 |

| Movements | four |

History

In December 1829, a year before the King of Prussia Frederick William III had even announced the tercentennial Augsburg celebrations, Mendelssohn began work on the Reformation Symphony. Mendelssohn hoped to have it performed at the festivities in Berlin which took place on 25 June 1830. He had intended to finish the composition by January 1830 and tour for four months before the celebrations began in June. However, his ill health caused the Reformation Symphony to take longer to compose than he had initially expected. In late March the symphony was still in a state of fabrication, and in an inauspicious turn of events Mendelssohn caught measles from his sister Rebecka. With a further delay of the composing and touring, Mendelssohn eventually completed the symphony in May. Unfortunately, it was too late for the Augsburg commission to recognize the symphony for the celebrations.

Some authorities have suggested that antisemitism may have played a role in the symphony's absence from Augsburg. But the successful competitor, Eduard Grell, had already established himself as a competent and successful composer who was gaining considerable popularity in Berlin. Grell was extremely conservative in his compositions; his piece for male chorus perhaps matched what the Augsburg celebrations demanded, in contrast to Mendelssohn's extensive symphony, which may have been thought inappropriate at the time.[2]

Mendelssohn resumed his touring immediately after he had completed the Reformation Symphony. In Paris, in 1832, François Antoine Habeneck's orchestra turned the work down as 'too learned'; the music historian Larry Todd suggests that perhaps they also felt it to be too Protestant.[3] He did not offer the symphony for performance at London. During the summer of 1832, Mendelssohn returned to Berlin where he revised the symphony. Later that year a performance of the Reformation Symphony finally took place.[4] By 1838 however Mendelssohn regarded the symphony as 'a piece of juvenilia', and he never performed it again. It was not performed again until 1868, more than 20 years after the composer's death.[5]

Key

The key of the symphony is stated as D major on the title page of Mendelssohn's autograph score. However, only the slow introduction is written in D major, whereas the main theme and the cadence setting of the first movement are in D minor. The composer himself referred to the symphony on at least one occasion as in D minor.[6]

Instrumentation

The symphony is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, "serpente" (possibly a serpent[7]) and contrabassoon (fourth movement only, now usually played on the contrabassoon alone), 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani and strings.

Movements

| External audio | |

|---|---|

| Performed by the Berlin Philharmonic under Herbert von Karajan | |

The symphony is in four movements:

- Andante – Allegro con fuoco (D major – D minor)

- Allegro vivace (B-flat major, trio in G major)

- Andante (G minor, ending in G major)

- Andante con moto – Allegro vivace – Allegro maestoso (G major – D major)

A typical performance lasts about 33 minutes.

First movement

During the slow introduction, Mendelssohn cites the "Dresden Amen" on the strings. Mendelssohn's version of the "Dresden Amen" is as follows:

(The theme was also used as the "Grail" leitmotif by Richard Wagner in his 1882 opera Parsifal.)

The strings are interrupted by battle-cries from the brass section as follows:

The "Dresden Amen" soon reappears on the strings and the Allegro con fuoco section, which is in sonata form, then begins. It opens as follows:

Second movement

The second movement, a B-flat major scherzo, is very different in spirit from the first movement, being much lighter in tone.

Third movement

The third movement, in G minor, is a lyrical piece primarily for the strings. There are references to the "Dresden Amen", and, at the movement's end, to the second theme of the first movement.

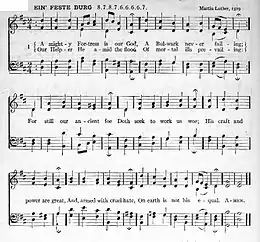

Fourth movement

The fourth movement is based on Martin Luther's chorale "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" ("A mighty fortress is our God"). It is in sonata form and is mostly in 4

4 time. There are a few unmarked meter changes to 2

4 to fit the meter of the original chorale.[8] At the very end of the coda, a powerful version of Martin Luther's chorale is played by the entire orchestra.

Notes

- Citron, Marcia J. (1987). The Letters of Fanny Hensel to Felix Mendelssohn. New York: Pendragon Press. pp. 97, 99, 101. ISBN 0-918728-52-5.

- Silber (1987),322–4

- Todd (2003), 254

- Silber (1987),331–2

- Silber (1987),333

- Silber (1987),329

- the standard Italian term for serpent (the musical instrument) is serpentone

- Kirill Polyanskiy's analysis of Mendelssohn's Fifth Symphony

References

- Heuss, Alfred. 1904. "The 'Dresden Amen': In the First Movement of Mendelssohn's 'Reformation' Symphony." The Musical Times 45, no. 737 (4 July): 441–42.

- Silber, Judith. 1987. "Mendelssohn and His 'Reformation' Symphony." Journal of the American Musicological Society 40, no. 2 (Summer): 310–36.

- Taylor, Benedict. 2009. 'Beyond Good and Programmatic: Mendelssohn's 'Reformation' Symphony', Ad Parnassum, 7/14 (October 2009): 115-27.

- Todd, R. Larry. 2003. Mendelssohn – A Life in Music. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511043-9.

External links

- Symphony No. 5: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project