Symphony No. 4 (Sibelius)

The Symphony No. 4 in A minor, Op. 63, is one of seven completed symphonies composed by Jean Sibelius. Written between 1910 and 1911, it was premiered in Helsinki on 3 April 1911 by the Philharmonia Society, with Sibelius conducting.

| Symphony No. 4 | |

|---|---|

| by Jean Sibelius | |

Sibelius in 1913. Some commentators have felt that the tensions of the Fourth Symphony reflect the atmosphere of Europe in the period leading to the First World War | |

| Key | A minor |

| Catalogue | Op. 63 |

| Composed | 1910–11 |

Instrumentation

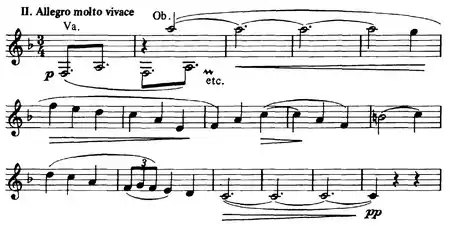

It is scored for an orchestra including 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets (in B♭ and A), 2 bassoons, 4 horns (in F and E), 2 trumpets (in F and E), 3 trombones, timpani, glockenspiel or/and tubular bells, and strings.

Movements

| External audio | |

|---|---|

| Performed by the Berlin Philharmonic under Herbert von Karajan | |

The work comprises four movements:

For this work Sibelius reversed the traditional classical positions of the second and third movements, placing the slow movement as the third. He also begins the piece with a slow movement instead of the traditional fast opening movement (this is the same order as many baroque orchestral works). A typical performance lasts between 35–40 minutes.

Analysis

The interval of the tritone dominates the melodic and harmonic material of the piece, but in a completely different way from how it dominates the Third Symphony. It is stated immediately, in a dark phrase for cellos, double basses and bassoons, rising C-D-F♯-E over a hard unison C.

Most of the themes of the symphony involve the tritone; in the finale, much of the harmonic tension arises from a collision between the keys of A minor and E♭ major, a tritone apart. The bitonal clash between A and E♭ in the finale's recapitulation leads to tonal chaos in the coda, in which the rival notes C, A, E♭ and F♯ (that is, the interlocking tritone pairs C–F♯, A–E♭) each strive for ascendancy in a series of grinding dissonances with many clashes between major and minor thirds.

The glockenspiel tries in vain to hail the momentary establishment of A major; but in the end it is the insistence of C♮ (the note with which the work so strikingly began) that forces the movement and the symphony to close in a desolate A minor, without of melody or rhythmic pulse.[1]

Many commentators have heard in the symphony evidence of struggle or despair. Harold Truscott writes, "This work ... is full of a foreboding which is probably the unconscious result of ... the sensing of an atmosphere which was to explode in 1914 into a world war."[2] Sibelius had also recently endured terrors in his personal life: in 1908, in Berlin, he had a cancerous tumour removed from his throat. Timothy Day writes that "the operation was successful, but he lived for many years in constant fear of the tumour recurring, and from 1908 to 1913 the shadow of death lay over his life."[3] Other critics have heard bleakness in the work: one early Finnish critic, Elmer Diktonius, dubbed the work the Barkbröd symphony,[4] referring to the famine in the previous century during which starving Scandinavians had had to eat bark bread to survive.

According to Sibelius' biographer Erik W. Tawaststjerna, the symphony reflects the psychoanalytical and introspective era when Sigmund Freud and Henri Bergson stressed the meaning of the unconscious,[5] and he calls the Fourth Symphony "one of the most remarkable documents of the psychoanalytical era."[6] Even Sibelius himself called his composition "a psychological symphony".[7] His brother, the psychiatrist Christian Sibelius (1869–1922), was one of the first scholars to discuss psychoanalysis in Finland.

In the year before beginning the symphony, Sibelius had met many of his contemporaries in central Europe, including Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, and others; his encounter with their music provoked a crisis in his own compositional life. He said in a letter to his friend (and biographer) Rosa Newmarch about the symphony: "It stands as a protest against present-day music. It has absolutely nothing of the circus about it." Later, when asked about the symphony, he quoted August Strindberg: "Det är synd om människorna" (One feels pity for human beings).

The symphony briefly had a nickname, "Lucus a non lucendo", an expression that literally means "a grove from not shining", suggesting, in this case, a place where light does not penetrate.[8]

Notes

- Lionel Pike, pp. 106–13

- Harold Truscott, p. 98.

- Timothy Day, p. 6

- Parmet, Simon (1962). Sävelestä sanaan: Esseitä, p. 94. Helsinki: WSOY.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (1989). Jean Sibelius 3, pp. 8, 239, 265. Helsinki: Otava. ISBN 951-1-10416-0

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (1989). Jean Sibelius 3, p. 265.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (1989). Jean Sibelius 3, p. 239.

- March 1, 1913 Musical Times, page 193, review of a 1913 Copenhagen performance.

References and further reading

- Hepokoski, James & Dahlström, Fabian: "Jean Sibelius", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed 3 April 2006), (subscription access)

- Truscott, Harold: "Jean Sibelius", in The Symphony, ed. Robert Simpson. Penguin Books Ltd., Middlesex, England, 1967. ISBN 0-14-020773-2

- Day, Timothy: program notes to Sibelius, The Symphonies (Lorin Maazel, Wiener Philharmoniker) (London/Decca CD 430 778-2)

- Parmet, Simon: Sävelestä sanaan: Esseitä. Helsinki: WSOY, 1962.

- Pike, Lionel: Beethoven, Sibelius and 'the Profound Logic'. London: The Athlone Press, 1978. ISBN 0-485-11178-0.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik: Jean Sibelius 3. Helsinki: Otava, 1989. ISBN 951-1-10416-0