Stylonurina

Stylonurina is one of two suborders of eurypterids, a group of extinct arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". Members of the suborder are collectively and informally known as "stylonurine eurypterids" or "stylonurines". They are known from deposits primarily in Europe and North America, but also in Siberia.[2]

| Stylonurina | |

|---|---|

| |

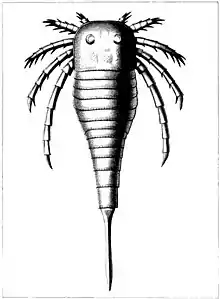

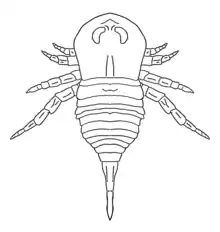

| The defining characteristic of stylonurine eurypterids is that the sixth pair of legs remain normal limbs used for walking. Reconstructed leg of Parastylonurus. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Suborder: | †Stylonurina Diener, 1924 |

| Clades | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Compared to the other suborder, Eurypterina, the stylonurines were comparatively rare and retained their posterior prosomal appendages for walking. Despite their rarity, the stylonurines have the longest temporal range of the two suborders. The suborder contains some of the oldest known eurypterids, such as Brachyopterus, from the Middle Ordovician as well as the youngest known eurypterids, from the Late Permian. They remained rare throughout the Ordovician and Silurian, though the radiation of the mycteropoids (a group of large sweep-feeding forms) in the Late Devonian and Carboniferous is the last major radiation of the eurypterids before their extinction in the Permian.[3]

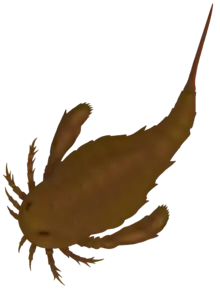

Though the Eurypterina contains several famous giant eurypterids such as Pterygotus and Jaekelopterus, the Stylonurina gave rise to large forms as well, several larger than a metre in length. The largest known stylonurine was Hibbertopterus scouleri, with a potential length of almost 2 meters.[4]

Description

Stylonurina contains a wide variety of different genera and species. They are all unified by possessing transverse sutures on the ventral plates and lacking a modified podomere 7a on appendage VI.[3]

The suborder is divided into four major superfamilies; the Rhenopteroidea, Stylonuroidea, Kokomopteroidea and Mycteropoidea. The most primitive of these, the Rhenopteroidea, includes several previously enigmatic genera, such as Brachyopterus, Kiaeropterus and Rhenopterus, all united by a rounded posterior margin to the metastoma and the prosomal appendage III bearing single fixed spines. Brachyopterus is also the currently oldest known genus of eurypterid, being from the Middle Ordovician.[3]

The least well-supported group is the Stylonuroidea, containing the problematic genera Stylonurus and Stylonurella, partly due to the incomplete nature of the only known specimen of Stylonurus powriei which does not preserve the anterior prosomal appendages or any details of the ventral structures. Specimens of other members of the group are similarly incomplete, with Stylonurella spinipes not preserving the metastoma or pretelson and telson and Pagea sturrocki not preserving any dorsal structures.[3]

The superfamilies Mycteropoidea and Kokomopteroidea are sister groups, united by a median ridge on the carapace between the lateral eyes and a distal thickening to the podomeres of the prosomal appendages. Though sometimes classified as an order separate from Eurypterida itself, the hibbertopterids are clearly recovered as stylonurine eurypterids in the latest analyses of the group.[3]

Convergent evolution of sweep-feeding

Strategies for sweep-feeding (raking through the substrate in search of prey) evolved independently in two of the four stylonurine superfamilies, the Stylonuroidea and the Mycteropoidea. In both superfamilies, the adaptations to this lifestyle involves modifications to the spines on their anterior prosomal appendages for raking through the substrate of their habitats. Rhenopteroids, kokomopterids and parastylonurids retained primitive prosomal appendages II-IV that were unsuited for sweep-feeding and likely adopted scavenging, whilst the hardieopterids may have been benthic bottomdwellers living partially buried in the substrate.[3]

Stylonuroids have fixed spines on appendages II-IV which could have been used as dragnets to rake through the sediments and thus entangling anything in their way, whilst the mycteropoids, which have some of the most extreme adaptations, likely were more selective and specialized. Mycteropoids possess modified blades on their anterior prosomal appendages that feature sensory setae. The tactile function of these might have allowed mycteropoids to select prey from the sediments in a way that stylonuroids could not.[3]

Systematics

Historically, the phylogeny and systematics of the Stylonurina have been far less well understood and less resolved than that of the Eurypterina. Many historical analyses were limited in scope or resolution and the unique hibbertopterids have even on occasion been suggested to be a separate, but closely related, order to Eurypterida, but have lacked an analysis either proving or disproving such an idea. Lamsdell et al. (2011) performed the first major and comprehensive analysis of the suborder, which permitted a substantial systematic revision and comparisons to other eurypterid clades.[3]

The phylogenetic analysis established that Stylonurina indeed was a monophyletic group composed of four clades: the Rhenopteroidea, Stylonuroidea, Kokomopteroidea and Mycteropoidea. These superfamilies in turn contain the following families (and one genus incertae sedis):[3]

Suborder Stylonurina Diener, 1924

- Stylonuroides (incertae sedis) Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Superfamily Rhenopteroidea Størmer, 1951

- Family Rhenopteridae Størmer, 1951

- Superfamily Stylonuroidea Kjellesvig-Waering, 1959

- Family Parastylonuridae Waterston, 1979

- Family Stylonuridae Diener, 1924

- Superfamily Kokomopteroidea Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Family Kokomopteridae Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Family Hardieopteridae Tollerton, 1989

- Superfamily Mycteropoidea Cope, 1886

- Family Drepanopteridae Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Family Hibbertopteridae Kjellesvig-Waering, 1959

- Family Mycteroptidae Cope, 1886

The cladogram presented below showcases the phylogeny of the Stylonurina as presented by Lamsdell et. al. (2010).[3] Alkenopterus (here shown as a rhenopterid) has since been reclassified as a basal eurypterine.[5]

| Stylonurina |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Drepanopterus

- Hibbertopterus

- Megarachne

- Eurypterid

- Eurypterina

- List of eurypterids

References

- James Lamsdell. "Systematic list of known eurypterid species". eurypterids.co.uk. Archived from the original on August 15, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- "Fossilworks: Stylonurina". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 2017-10-03.

- James C. Lamsdell, Simon J. Braddy & O. Erik Tetlie (2010). "The systematics and phylogeny of the Stylonurina (Arthropoda: Chelicerata: Eurypterida)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/14772011003603564.

- Tetlie, O. E. (2008). "Hallipterus excelsior, a Stylonurid (Chelicerata: Eurypterida) from the Late Devonian Catskill Delta Complex, and Its Phylogenetic Position in the Hardieopteridae". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 49: 19–99. doi:10.3374/0079-032X(2008)49[19:HEASCE]2.0.CO;2.

- Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2015. A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives. In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern, online at http://wsc.nmbe.ch, version 16.0 http://www.wsc.nmbe.ch/resources/fossils/Fossils16.0.pdf (PDF).