Stull, Kansas

Stull is an unincorporated community in Douglas County, Kansas, United States.[1] Founded in 1857, the settlement was initially known as Deer Creek until it was renamed after its only postmaster, Sylvester Stull. As of 2018, only a handful of structures remain in the area.

Stull, Kansas | |

|---|---|

A view of Stull looking southwest. The building on the left is the Stull United Methodist Church, and the building on the right is the fire station. | |

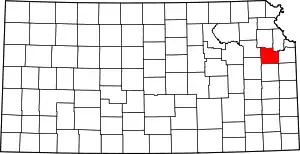

KDOT map of Douglas County (legend) | |

Stull Location within the U.S. state of Kansas  Stull Stull (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 38°58′16″N 95°27′22″W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kansas |

| County | Douglas |

| Founded | 1857 |

| Named for | Sylvester Stull |

| Elevation | 938 ft (286 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| Area code | 785 |

| FIPS code | 20-68725 [1] |

| GNIS ID | 0479114 [1] |

Since the 1970s, the town has become infamous due to an apocryphal legend that claims the nearby Stull Cemetery is possessed by demonic forces. This legend has become a facet of American popular culture and has been referenced in numerous forms of media. This legend has also led to controversies with current residents of Stull.

Geography

Stull is located at 38°58′16″N 95°27′32″W (38.9711124, -95.4560872),[1] at the corner of North 1600 Road (![]() CR-442) and East 250 Road (

CR-442) and East 250 Road (![]() CR-1023) in Douglas County, which is 7 miles west from the outskirts of Lawrence and 10 miles east of the Topeka city limit.

CR-1023) in Douglas County, which is 7 miles west from the outskirts of Lawrence and 10 miles east of the Topeka city limit.

History

Founding

Stull first appeared on territorial maps in 1857.[2][3] During this time, the settlement was called Deer Creek.[3] It is unclear where this name came from, although Martha Parker and Betty Laird speculate that it could either be a translation of an indigenous location name or that it could have arisen after a deer was seen by a body of water.[4] The first European settlers in the area spoke German as their native language.[5] Some had come from Pennsylvania Dutch Country, whereas others had recently fled the German Confederation "for more freedom and to escape military duty."[6]

19th century

During the late 1850s, the handful of families living in Deer Creek organized a church that met in the homes of its members until 1867, when a stone structure named the Evangelical Emmanuel and Deer Creek Mission was built; this church later became known simply as "Evangelical Emmanuel Church".[5][6] Until 1908, the sermons at the small chapel were preached in German.[5] In 1867, a cemetery was chartered for the town next to the church.[6][nb 1] In 1922, those living in Stull raised $20,000 to construct a new, wooden-framed church across the road. The following year, the church changed its official name from "Deer Creek Church" to "Stull Evangelical Church". The old stone Evangelical Emmanuel Church was abandoned by the community in 1922, and over the course of the 20th century, the church slowly fell into a greater and greater state of decrepitude, finally being demolished in 2002.[6][nb 2] Due to a growing congregation from Stull and Lecompton, a larger church was eventually needed, so in 1919, the community voted to build a new church. In 1922 a new church was built and eventually got the name “United Methodist Zion Church” in 1968.[6] This new church holds services and meetings that continue today under the name Stull United Methodist Church.[6]

In the late 1890s, a telephone switchboard was added to the house of a Stull resident named J. E. Louk, and soon thereafter, on April 27, 1899, a post office was established in the back of the very same building.[2][11] The town's first and only postmaster was Sylvester Stull, from whom the town derived its name.[11] According to Parker and Laird, the United States Post Office simply selected the name based on the name of the postmaster.[12] The name stuck even after the post office was discontinued in 1903.[11][12]

Stull residents opened two schools prior to Kansas being admitted to the Union. The first school only lasted for about five years, the other school named “Deer Creek” experienced increasing enrollments and started being used for church services by the Lutheran congregation and the United Brethren on Sundays. Along with church services, the school held debates, voting for general elections, and competitions in baseball, horseshoes, sewing, and cooking. The school continued until 1962 when it closed; students thereafter went to Lecompton to continue their education.[6]

Farming brought the community new hope and continues to be the common livelihood of the remaining residents. Construction on the Clinton Reservoir led to changes in road routes and farming locations. While this did mean the loss of farms to eminent domain and county purchase, it helped Stull and its surrounding communities become more progressive.[6][13]

20th century

In 1912, only 31 people lived in the Stull area, and at its maximum size the settlement comprised about fifty individuals.[11][14] Christ Kraft, an inhabitant of the settlement during the 20th century, recalls that life in the small town was "quiet and easy, sometimes even boring."[15] Before automobiles were popular in the area, trips to Lecompton, Lawrence, and Topeka, took two, three, and four hours, respectively. In early 20th century, organized baseball became popular in the area, and members of Stull played in a league with members from other Clinton Lake communities, like Clinton and Lone Star.[15] Eventually, a baseball diamond was constructed in Stull.[2] During this time, hunting rabbits was also a popular activity,[16] and it was not uncommon for the Stull community to bring hauls of about 300 freshly-killed rabbits to butchers in Topeka.[2]

During the early 20th century, a number of businesses were established in the area, but most were short-lived; the exception to this general trend was the Louk & Kraft grocery store, which was established in the early 1900s and lasted until 1955.[11][17] The Roaring Twenties brought preliminary discussion about constructing an interurban railroad line between Kansas City and Emporia that would have run through Stull.[18] Anticipating that their city was about to grow, the residents of Stull began discussing the idea of establishing a "Farmers State Bank" in the area; the Lecompton-based banker J. W. Kreider even secured an official bank charter.[2][15] However, neither the railway or the bank were ever built, possibly due to the advent of the Great Depression.[15]

During the 20th century, the settlement suffered two major tragedies. The first occurred when Oliver Bahnmaier, a young boy wandered into a field that his father was burning and died. Oliver’s tragic death led to the rumor that if one stepped on Oliver’s tombstone, they would go to Hell. The second occurred when a man was found hanging from a tree after going missing.[11][19]

Legend of Stull Cemetery

The opening to the University Daily Kansan article "Legend of Devil Haunts Tiny Town", penned by Jain Penner.[20] It was this article that caused Stull to largely be associated with the supernatural in the popular consciousness.[7]

The Stull Cemetery[21] has gained an ominous reputation due to urban legends involving Satan, the occult, and a purported "gateway to Hell".[22] The rumors about the cemetery were popularized by a November 1974 issue of The University Daily Kansan (the student newspaper of the University of Kansas), which claimed that the Devil appeared in Stull twice a year: once on Halloween, and once on the spring equinox.[23][10] People soon said that the cemetery was the location of one of the seven gates to Hell and that the nearby Evangelical Emmanuel Church ruin was "possessed" by the Devil. Others claimed (erroneously) that the legend was engendered by the killing of Stull’s mayor back in the 1850s (of note, Stull was never organized as a town, so never had a mayor).[6] It is also said that during a trip to Colorado in the 1990s, the Pope redirected the flight path of his private plane to avoid flying over the unholy ground of Stull (although there is no evidence that this happened).[22] Most academics, historians, and local residents are in agreement that the legend has no basis in historical fact and was created and spread by students.[7][10]

In the years that followed the publication of the University Daily Kansan article, the legend persuaded thrill seekers to visit the cemetery, and they would claim that weird and creepy events such as noises and memory lapses happened to them leading to further speculation that the town was haunted by witches and the devil. It became a popular activity for young folks (especially high school and college students from Lawrence or Topeka) to journey to the cemetery on Halloween or the equinox to "see the Devil". Many would jump fences or otherwise sneak their way onto the property. Over the decades, as the number of people making excursions to the cemetery grew, the graveyard started to deteriorate; this was exacerbated by vandals.[7][10] To combat this, the county's sheriff office patrols the area around the cemetery, especially on Halloween, and will arrest people for trespassing.[24] Those caught inside the cemetery after it is closed could face a maximum fine of $1,000 and up to six months in jail.[22]

In popular culture

Despite its dubious origins, the legend of Stull Cemetery has been referenced numerous times in popular culture. The band Urge Overkill released Stull in 1992, which features the church and a tombstone from the cemetery on the cover.[7][25] It has been argued that the British band The Cure canceled their show in Kansas because of Stull’s cemetery,[22] although this too is false.[7] Films whose plot is based on the legends include Turbulence 3: Heavy Metal (2001),[26] Nothing Left to Fear (2013),[27] and the unreleased film Sin-Jin Smyth.[26] The cemetery is also the site of the final confrontation between Lucifer and Michael in "Swan Song", the season five finale of the television series Supernatural and the History Channel documentary.[7][28] In-universe, Sam and Dean Winchester (the series' protagonists) are from Lawrence; in a 2006 interview, Eric Kripke (the creator of Supernatural) revealed that he decided to have the two brothers be from Lawrence because of its closeness to Stull.[29] In an interview with Complex Magazine, pop star Ariana Grande talked about her unsuccessful attempt to visit Stull and stated that she was attacked by demons.[30]

Gallery

The Stull fire department.

The Stull fire department. The outside of the United Methodist Church. The church continues to hold services every Sunday.

The outside of the United Methodist Church. The church continues to hold services every Sunday. The Stull cemetery in 2019.

The Stull cemetery in 2019. Stull Cemetery (facing northeast) in 2014.

Stull Cemetery (facing northeast) in 2014. Stull Cemetery (facing northeast) in 2007. The remnants of the old church are visible in the background.

Stull Cemetery (facing northeast) in 2007. The remnants of the old church are visible in the background. Cover of Stull by Urge Overkill. The now-destroyed chapel is in the background.

Cover of Stull by Urge Overkill. The now-destroyed chapel is in the background.

See also

- Kanwaka Township, Douglas County, Kansas (location of Stull)

- Clinton Lake, southeast of Stull

- List of reportedly haunted locations in the United States

Explanatory notes

- This cemetery is not to be confused with Mound View Cemetery, also known as "Old Stull Cemetery", which is located just south of the small town. Some people claim that this is the 'real' Stull Cemetery to which the notorious legends allude, but this seems to be a recent addition to the legend.[7]

- In the 1990s, the structure's lost its roof during a microburst.[5] By the turn of the 21st century, the eastern wall of the church ruin had buckled after years of neglect, and in early 2002, the structure's western wall caved in following another strong windstorm. In March of that year, the building was bulldozed. Initially, locals were unsure who had approved the razing, but it was eventually revealed that John Haase, a Lecompton resident who owned the land upon where the church was located, had authorized the demolition after the Douglas County sheriff's department informed him that it was a safety risk.[8][9] Prior to the structure's collapse, some of the residents in Stull wanted to rebuild the stone church, although these efforts never materialized.[10]

References

Footnotes

- "Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) details for Stull, Kansas; United States Geological Survey (USGS)". United States Board on Geographic Names. October 13, 1978. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Stull Bicentennial Committee (1976).

- Thomas (2017), p. 116.

- Parker & Laird (1976), p. 93.

- Parker & Laird (1976), pp. 93–4.

- Lecompton Historical Society (1990).

- Thomas (2017), pp. 116–24.

- Paget, Mindie (March 30, 2002). "Building's Demolition a Mystery". Lawrence Journal-World. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "Local Briefs—Stull: Property Owner Authorized Razing of Abandoned Church". Lawrence Journal-World. March 31, 2002. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Heitz (1997), pp. 102–07.

- Fitzgerald (2009), p. 103.

- Parker & Laird (1976), p. 98.

- Nichols, Raymond (1977). The History of Stull. Russel Spencer. pp. 1–8.

- Blackmar (1912), p. 782.

- Parker & Laird (1976), p. 101.

- Parker & Laird (1976), p. 102.

- Carpenter, Tim (November 28, 1997). "What's in a Name? Key Elements of Area History". Lawrence Journal-World. p. 3B. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- Chambers and Tompkins (1977), p. 42.

- Parker & Laird (1976), pp. 102–3.

- Penner, Jain (November 5, 1974). "Legend of Devil Haunts Tiny Town". The University Daily Kansan.

- "Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) details for Stull Cemetery, Kansas; United States Geological Survey (USGS)". United States Board on Geographic Names. July 22, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Gintowt, Richard (October 26, 2004). "Hell Hath No Fury". Lawrence.com. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Smarsh (2010), p. 117.

- Seba, Erwin (November 1, 1999). "Legends Linger Around Stull". Lawrence Journal-World. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Kugelberg (1992), p. 16.

- "The Most Haunted Place in Every State (Slideshow)". The Daily Meal. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Turek, Ryan (May 29, 2012). "Slash Talks Producing Nothing to Fear". STYD. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- Engstrom (2014), p. 95.

- Kripke, Eric (October 12, 2006). "Supernatural: Your Burning Questions Answered!". TV Guide. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Thomas, Paul (October 9, 2017). Haunted Lawrence. p. 124.

Bibliography

- Blackmar, Frank, ed. (1912). "Stull". Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, etc. Chicago, IL: Standard Publishing Company. p. 782. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- Chambers, Mary Elizabeth; Tompkins, Sally Kress (1977). The Cultural Resources of Clinton Lake, Kansas: An Inventory of Archaeology, History, and Architecture. Fairfax, VA: Iroquois Research Institute.

- Engstrom, Erika; III, Joseph M. Valenzano (2014). Television, Religion, and Supernatural: Hunting Monsters, Finding Gods. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739184769.

- Fitzgerald, Daniel (2009). Ghost Towns of Kansas. 2. Dan Fitzgerald Company. ISBN 9781449505196.

- Heitz, Lisa Hefner (1997). "The Demonic Church". Haunted Kansas. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. pp. 102–07. ISBN 9780700609307.

- Kugelberg, Johan (July 1992). "Playboys of the Midwestern World". Spin. 8 (4). Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- Lecompton Historical Society (Spring 1990). "Our Neighboring Community: Stull" (PDF). Bald Eagle. Lecompton, KS. 16 (1): 1–5. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- Parker, Martha; Laird, Betty (1976). "Stull". Soil of Our Souls: Histories of the Clinton Lake Communities. Lawrence, KS: Coronado Press.

- Smarsh, Sarah (2010). It Happened in Kansas: Remarkable Events that Shaped History. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780762766444.

- Stull Bicentennial Committee (1976). The History of Stull, 1857–1976. Stull, KS: Stull Extension Homemakers Unit.

- Thomas, Paul (2017). "Stull Cemetery". Haunted Lawrence. Haunted America. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 9781625859204.

- Nichols, Raymond (1977). The History of Stull. Russel Spencer. pp. 1–8.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stull, Kansas. |