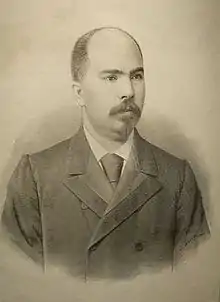

Stefan Stambolov

Stefan Nikolov Stambolov (Bulgarian: Стефан Николов Стамболов) (31 January 1854 OS– 19 July 1895 OS) was a Bulgarian politician, journalist, revolutionist, and poet who served as Prime Minister and regent.[1][2] He is considered one of the most important and popular "Founders of Modern Bulgaria", and is sometimes referred to as "the Bulgarian Bismarck". In 1875 and 1876 he took part in the preparation for the Stara Zagora uprising, as well as the April Uprising. Stambolov was, after Stanko Todorov, Boyko Borisov and Todor Zhivkov, one of the country's longest-serving prime ministers. Criticised for his dictatorial methods, he was among the initiators of economic and cultural progress in Bulgaria during the time of the Balkan Wars.

Stefan Stambolov Стефан Стамболов | |

|---|---|

| |

| 9th Prime Minister of Bulgaria | |

| In office 1 September 1887 – 31 May 1894 | |

| Monarch | Ferdinand |

| Preceded by | Konstantin Stoilov |

| Succeeded by | Konstantin Stoilov |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 February 1854 Tırnovo, Ottoman Empire (now Veliko Tărnovo, present-day Bulgaria) |

| Died | 19 July 1895 (aged 41) Sofia, Principality of Bulgaria |

| Resting place | Central Sofia Cemetery |

| Nationality | Bulgarian |

| Political party | Liberal Party, People's Liberal Party |

| Occupation | Statesman, Poet |

Early years

Stambolov was born in Veliko Tarnovo. His father took part in the "Velchova Zavera" plot against Turkish rule in 1835. Stambolov grew up around prominent revolutionists like Hristo Ivanov, the priest Matey Preobrazhenski, and Hristo Karaminkov. He began his education in his home town, but later (1870–1872) studied at the Seminary in Odessa. In 1878 he was for a short period of time a teacher in his home town, and later he went to Romania. He joined the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee (BRCC). After the death of BRCC founder Vassil Levski, Stambolov was chosen as his successor. He was the leader of the unsuccessful uprising in Stara Zagora in 1875 and of the Turnovo revolutionary committee in the great uprising of April 1876.

Political career

Stambolov was involved in political discussions as early as the time of the first Bulgarian parliament: the "Founding Assembly" of 1879. After 1880 he became the vice-chairman and later the chairman of the Narodno Subranie (the Bulgarian parliament). In 1885, he helped bring about the union of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia. On 20 August [O.S. 9 August] 1886, officers aligned with Russia overthrew Prince Alexander in a coup d'état. Stambolov led a counter-coup on 28 August which removed the Russian-controlled provisional government, and he assumed the position of regent. Russian hostility, however, barred the restoration of Alexander, who abdicated on 8 September.

Regency

At the age of 32, Stambolov found himself in the highly unusual position of being simultaneously a government minister, president, and regent for an absent monarch. Stambolov's style of governing during his regency was observed as being increasingly authoritarian. But this was, to some extent, a reaction to the grave difficulties arising from his peculiar position. Indeed, the regency has been described as marking the beginning of the tragic years of Stambolov's life.

According to a close friend, Stambolov was "almost inclined to resign the honours [of serving as regent], together with the dangers of his position, and retire to his beloved Turnovo." But he stayed on, recognizing that there was no other suitable candidate, and that if he did not lead, then Bulgaria's sovereignty would likely be lost.

Through Stambolov's efforts, a successor to Alexander was found in Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, who was proclaimed Knyaz ("Ruling Prince") of autonomous Bulgaria on 7 July 1887 and crowned on 14 August 1887. However, it is known that Stambolov initially supported Carol I of Romania and that he intended to establish a union with the country. Russian opposition forced Carol I to reject the offer. Stambolov also requested to the Ottoman Empire a dual Bulgarian-Turkish state.[3]

Prime minister

With Ferdinand's accession to the throne, Stambolov retired as regent, and became Prime Minister. He served for seven years (1887–1894).

Stambolov was a nationalist; as a politician, he strengthened the country's diplomacy, its economy, and the general political power of the state.

He confronted Knyaz Ferdinand, and blocked his schemes to usurp additional authority. This caused him a lot of stress, and he became distant from his friends, and suspicious of all around him. The public came to dislike him, as he took increasingly drastic measures against his enemies. He survived an assassination attempt unharmed, but responded by having many people he suspected of taking part imprisoned and treated brutally.

By 1894 the prolonged stress from all sides had taken its toll, and Stambolov resigned, which was happily accepted by Ferdinand.

Death

On 15 July 1895, Stambolov took a carriage to his home, along with his bodyguard and a friend. Midway, the carriage was stopped by an assassin who fired his revolver, thus startling the horses. Stambolov quickly exited, but was met by three more assassins, armed with knives. Stambolov, who carried a revolver, shot one of the attackers. The others wrestled him to the ground. They knew that Stambolov wore an armoured vest, so they stabbed at his head, which he tried to protect with his hands. His bodyguard finally chased away the assailants.

Stambolov was hurried to his home with a fractured skull and mutilated hands. He is supposed to have said on his deathbed, "Bulgaria's people will forgive me everything. But they will not forgive that it was I who brought Ferdinand here." It is believed that Stambolov was well-aware that his days after his resignation were numbered, and that Ferdinand was likely to be the one who would orchestrate an assassination.

He died at about 2.00 a.m. on 18 July.

Assessment

Stambolov believed that the liberation of Bulgaria was an attempt by Czarist Russia to turn Bulgaria into its protectorate. His policy was characterized by the goal of preserving Bulgarian independence at all costs. During his leadership Bulgaria was transformed from an Ottoman province into a modern European state.

Stambolov launched a new course in Bulgarian foreign policy, independent of the interests of any great power. His main foreign policy objective was the unification of the Bulgarian nation into a nation-state consisting of all the territories of the Bulgarian Exarchate granted by the Sultan in 1870. Stambolov established close connections with the Sultan in order to enliven Bulgarian national spirit in Macedonia and to oppose Russian-backed Greek and Serbian propaganda. As a result of Stambolov’s tactics, the Sultan recognised Bulgarians as the predominant people in Macedonia and gave a green light to the creation of a strong church and cultural institutions.

Stambolov negotiated loans with western European countries to develop the economic and military strength of Bulgaria. In part, this was motivated by his desire to create a modern army which could secure all of the national territory.

His approach toward western Europe was one of diplomatic manoeuvring. He understood the interests of the Austrian Empire in Macedonia and warned his diplomats accordingly. His domestic policy was distinguished by the defeat of terrorist groups sponsored by Russia, the strengthening of the rule of law, and rapid economic and educational growth, leading to progressive social and cultural change, and development of a modern army capable of protecting Bulgaria's independence.

Stambolov was aware that Bulgaria had to be politically, militarily, and economically strong to achieve national unification. He mapped out the political course which turned Bulgaria into a strong regional power, respected by the great powers of the day. However, Bulgaria’s regional leadership was short-lived. After Stambolov's death the independent course of his policy was abandoned.

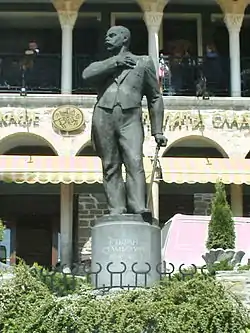

Honours

Stambolov Crag on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica, is named for him.

Stambolov is portrayed on the obverse of the Bulgarian 20 levs banknote, issued in 1999, 2007 and 2020.[4]

References

- J. D. B. (1911). "Stambolov, Stefan". The Encyclopaedia Britannica; A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. XXV (SHUVALOV to SUBLIMINAL SELF) (11th ed.). Cambridge, England and New York: At the University Press. p. 768. Retrieved 16 July 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Gilman, Daniel Coit; Peck, Harry Thurston; Colby, Frank Moore, eds. (1904). "STAMBULOFF, Stephen". The New International Encyclopaedia. XVI (SOU-TYP). New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. pp. 130–131. Retrieved February 23, 2019 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- Nyagulov, Blagovest (2012). "Ideas of federation and personal union with regard to Bulgaria and Romania". Bulgarian Historical Review (3–4): 36–61. ISSN 0204-8906.

- Bulgarian National Bank. Notes and Coins in Circulation: 20 levs (1999 issue) & 20 levs (2007 issue). – Retrieved on 26 March 2009.

Bibliography

- Beaman, A. Hulme (1895). M. Stambuloff. New York: Frederick Warne. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- Hulme Beaman, Ardern George (1898). Twenty Years in the Near East. London: Methuen & Co. pp. 170–183. hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t3kw5gb9c.

- Perry, Duncan M. (1993). Stefan Stambolov and the Emergence of Modern Bulgaria, 1870-1895. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Works by or about Stefan Stambolov in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Konstantin Stoilov |

Prime Minister of Bulgaria 1887-1894 |

Succeeded by Konstantin Stoilov |

| Regnal titles | ||

| Preceded by Prince Alexander of Battenberg |

Rulers of Bulgaria 1886-1887 |

Succeeded by Ferdinand I of Bulgaria |