Steel-string acoustic guitar

The steel-string acoustic guitar is a modern form of guitar that descends from the nylon-strung classical guitar, but is strung with steel strings for a brighter, louder sound. Like the classical guitar, it is often referred to simply as an acoustic guitar.

A Gibson SJ200 model | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | String instrument (plucked) |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.322-6 (Composite chordophone sounded by a plectrum) |

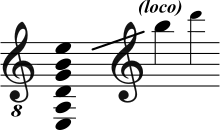

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| |

.jpg.webp)

The most common type is often called a flat top guitar, to distinguish it from the more specialized archtop guitar and other variations.

The standard tuning for an acoustic guitar is E-A-D-G-B-E (low to high), although many players, particularly fingerpickers, use alternate tunings (scordatura), such as open G (D-G-D-G-B-D), open D (D-A-D-F♯-A-D), drop D (D-A-D-G-B-E), or D-A-D-G-A-D (particularly in Irish traditional music).

Construction

Steel-string guitars vary in construction and materials. Different woods and approach to bracing affect the instrument's timbre or tone. While there is little scientific evidence, many players and luthiers believe a well-made guitar's tone improves over time. They theorize that a decrease in the content of hemicellulose, crystallization of cellulose, and changes to lignin over time all result in its wood gaining better resonating properties.[1]

Types

Steel-string acoustic guitars are commonly constructed in several body types, varying in size, depth, and proportion. In general, the guitar's soundbox can be thought of as composed of two mating chambers: the upper bouts (a bout being the rounded corner of an instrument body) on the neck end of the body, and lower bouts (on the bridge end). These meet at the waist, or the narrowest part of the body face near the soundhole. The proportion and overall size of these two parts helps determine the overall tonal balance and "native sound" of a particular body style – the larger the body, the louder the volume.

- The 00, double-O or grand concert body type is the major body style most directly derived from the classical guitar. It has the thinnest soundbox and the smallest overall size, making it very comfortable to play but lacking in projection -volume - relative to the larger types. Its smaller size makes it suitable for younger or smaller-framed players. It is commonly called a "parlor steel", as it is well-suited to smaller rooms. Martin's 00-xxx series and Taylor's x12 series are common examples.

- The grand auditorium guitar, sometimes called the 000 or the triple-O is very similar in design to the grand concert, but slightly wider and deeper. Many 000-style guitars also have a convex back to increase the physical volume of the soundbox without making it deeper at the edges, which would affect comfort and playability. The result is a very balanced tone, comparable to the 00 but with greater volume and dynamic range and slightly more low-end response, making this Classically shaped body style very popular. Eric Clapton's signature Martin, for example, is of this style. Martin's 000-xxx series and Taylor's x14 series are well-known examples of the grand auditorium style.

- The dreadnought is a large-bodied guitar which incorporates a deeper soundbox, but a smaller and less-pronounced upper bout than most styles. Its size and power gave rise to its name, from the most formidable class of warship at the time of its creation in the early 20th century. The style was designed by Martin Guitars[2] to produce a deeper sound than "classic"-style guitars, with very resonant bass. Its body's combination of compact profile with a deep sound has since been copied by virtually every major steel-string luthier, making it the most popular body type. Martin's "D" series guitars, such as the highly prized D-28, are classic examples of the dreadnought.

- The jumbo body type is bigger again than a grand auditorium but similarly proportioned, and is generally designed to provide a deep tone similar to a dreadnought's. It was designed by Gibson to compete with the dreadnought,[2] but with maximum resonant space for greater volume and sustain. These come at the expense of being oversized, with a very deep sounding box, and thus somewhat more difficult to play. The foremost example of the style is the Gibson J-200, but like the dreadnought, most guitar manufacturers have at least one jumbo model.

Any of these body type can incorporate a cutaway, where a section of the upper bout below the neck is scalloped out. This allows for easier access to the frets located atop the soundbox, at the expense of reduced soundbox volume and altered bracing, which can affect the resonant qualities and resulting tone of the instrument.

All of these relatively traditional looking and constructed instruments are commonly referred to as flattop guitars. All are commonly used in popular music genres, including rock, blues, country, and folk.

Other styles of guitar which enjoy moderate popularity, generally in more specific genres, include:

- The archtop, which incorporates an arched, violin-like top either carved out of solid wood or heat-pressed using laminations. It usually has violin style f-holes rather than a single round sound hole. It is most commonly used by swing and jazz players and often incorporates an electric pickup.

- The Selmer-Maccaferri guitar is usually played by those who follow the style of Django Reinhardt. It is an unusual-looking instrument, distinguished by a fairly large body with squarish bouts, and either a D-shaped or longitudinal oval soundhole. The strings are gathered at the tail like an archtop guitar, but the top is flatter. It also has a wide fingerboard and slotted head like a nylon-string guitar. The loud volume and penetrating tone make it suitable for single-note soloing, and it is frequently employed as a lead instrument in gypsy swing.

- The resonator guitar, also called the Dobro after its most prominent manufacturer, amplifies its sound through one or more metal cone-shaped resonators. It was designed to overcome the problem of conventional acoustic guitars being overwhelmed by horns and percussion instruments in dance orchestras. It became prized for its distinctive sound, however, and gained a place in several musical styles (most notably blues and bluegrass), and retains a niche well after the proliferation of electric amplification.

- The 12-string guitar replaces each string with a course of two strings. The lower pairs are tuned an octave apart. Its unique sound was made famous by artists such as Lead Belly, Pete Seeger and Leo Kottke.

Tonewoods

Traditionally, steel-string guitars have been made of a combination of various tonewoods, or woods considered to have pleasing resonant qualities when used in instrument-making. Note that the term is ill-defined - the wood species that are considered tonewoods have evolved throughout history.[3] Foremost for making steel-string guitar tops are Sitka spruce, the most common, and Alpine and Adirondack spruce. The back and sides of a particular guitar are typically made of the same wood; Brazilian rosewood, East Indian rosewood, and Honduras mahogany are traditional choices, however, maple has been prized for the figuring that can be seen when it is cut in a certain way (such as flame and quilt patterns). A common non-traditional wood gaining popularity is sapele, which is tonally similar to mahogany but slightly lighter in color and possessing a deep grain structure that is visually appealing.

Due to decreasing availability and rising prices of premium-quality traditional tonewoods, many manufacturers have begun experimenting with alternative species of woods or more commonly available variations on the standard species. For example, some makers have begun producing models with red cedar or mahogany tops, or with spruce variants other than Sitka. Cedar is also common in the back and sides, as is basswood. Entry-level models, especially those made in East Asia, often use nato wood, which is again tonally similar to mahogany but is cheap to acquire. Some have also begun using non-wood materials, such as plastic or graphite. Carbon-fiber and phenolic composite materials have become desirable for building necks, and some high-end luthiers produce all-carbon-fiber guitars.

Assembly

The steel-string acoustic guitar evolved from the gut-string classical guitar, and because steel strings have higher tension, heavier construction is required overall. One innovation is a metal bar called a truss rod, which is incorporated into the neck to strengthen it and provide adjustable counter-tension to the stress of the strings. Typically, a steel-string acoustic guitar is built with a larger soundbox than a standard classical guitar. A critical structural and tonal component of an acoustic guitar is the bracing, a systems of struts glued to the inside of the back and top. Steel-string guitars use different bracing systems from classical guitars, typically using X-bracing instead of fan bracing. (Another simpler system, called ladder bracing, where the braces are all placed across the width of the instrument, is used on all types of flat-top guitars on the back.) Innovations in bracing design have emerged, notably the A-brace developed by British luthier Roger Bucknall of Fylde Guitars.

Most luthiers and experienced players agree that a good solid top (as opposed to laminated or plywood) is the most important factor in the tone of the guitar. Solid backs and sides can also contribute to a pleasant sound, although laminated sides and backs are acceptable alternatives, commonly found in mid-level guitars (in the range of US$300–$1000).

From the 1960s through the 1980s, "by far the most significant developments in the design and construction of acoustic guitars" were made by the Ovation Guitar Company.[4] It introduced a composite roundback bowl, which replaced the square back and sides of traditional guitars; because of its engineering design, Ovation guitars could be amplified without producing the obnoxious feedback that had plagued acoustic guitars before. Ovation also pioneered with electronics, such as pickup systems and electronic tuners.[4][5]

Amplification

A steel-string guitar can be amplified using any of three techniques:

- a microphone, possibly clipped to the guitar body;

- a detachable pickup, often straddling the soundhole and using the same magnetic principle as a traditional electric guitar; or

- a transducer built into the body.

The last type of guitar is commonly called an acoustic-electric guitar as it can be played either "unplugged" as an acoustic, or plugged in as an electric. The most common type is a piezoelectric pickup, which is composed of a thin sandwich of quartz crystal. When compressed, the crystal produces a small electric current, so when placed under the bridge saddle, the vibrations of the strings through the saddle, and of the body of the instrument, are converted to a weak electrical signal. This signal is often sent to a pre-amplifier, which increases the signal strength and normally incorporates an equalizer. The output of the preamplifier then goes to a separate amplifier system similar to that for an electric guitar.

Several manufacturers produce specialised acoustic guitar amplifiers, which are designed to give undistorted and full-range reproduction.

Music and players

Until the 1960s, the predominant forms of music played on the flat-top, steel-string guitar remained relatively stable and included acoustic blues, country, bluegrass, folk, and several genres of rock. The concept of playing solo steel-string guitar in a concert setting was introduced in the early 1960s by such performers as Davey Graham and John Fahey, who used country blues fingerpicking techniques to compose original compositions with structures somewhat like European classical music. Fahey contemporary Robbie Basho added elements of Indian classical music and Leo Kottke used a Faheyesque approach to make the first solo steel-string guitar "hit" record.

Steel-string guitars are also important in the world of flatpicking, as utilized by such artists as Clarence White, Tony Rice, Bryan Sutton, Doc Watson and David Grier. Luthiers have been experimenting with redesigning the acoustic guitar for these players. These flat-top, steel-string guitars are constructed and voiced more for classical-like fingerpicking and less for chordal accompaniment (strumming). Some luthiers have increasingly focused their attention on the needs of fingerstylists and have developed unique guitars for this style of playing.

Many other luthiers attempt to recreate the guitars of the "Golden Era" of C.F. Martin & Co. This was started by Roy Noble, who built the guitar played by Clarence White from 1968 to 1972, and was followed by Bill Collings, Marty Lanham, Dana Bourgeois, Randy Lucas, Lynn Dudenbostel and Wayne Henderson, a few of the luthiers building guitars today inspired by vintage Martins, the pre–World War II models in particular. As prices for vintage Martins continue to rise exponentially, upscale guitar enthusiasts have demanded faithful recreations and luthiers are working to fill that demand.

References

- October 02, Rick Turner; 2013. "Acoustic Soundboard: The Sonic Effect of Time and Vibration". www.premierguitar.com. Retrieved 2019-09-12.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Acoustic Guitar Buying Guide". www.sweetwater.com. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- Mottola, R.M. (1 January 2020). Mottola's Cyclopedic Dictionary of Lutherie Terms. LiutaioMottola.com. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-7341256-0-3.

- Denyer, Ralph (1992). "Ovation guitars (Acoustic guitars)". The guitar handbook. Special contributors Isaac Guillory and Alastair M. Crawford; Robert Fripp (foreword) (Fully revised and updated ed.). London and Sydney: Pan Books. p. 48. ISBN 0-330-32750-X.

-

- Anonymous, Music Trades (1 October 2004). "Ovation's encore: How a host of product refinements have rekindled growth at Kaman Music's flagship guitar division". The Music Trades. The Guitar Market. (subscription required). Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- Carter, Walter (1996). Eiche, Jon (ed.). The history of the Ovation guitar. Musical Instruments Series (first ed.). Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Hal Leonard Corporation. pp. 1–128. ISBN 978-0-7935-5876-6. HL00330187.

- Cruice, Valerie (December 8, 1996). "From the ratcheting of helicopters to a guitar's hum". The New York Times.

- Marks, Brenda (30–31 May 1999). "Connecticut firm makes guitars, helicopter blades from same fiberglass". Waterbury Republican-American. New Hartford, Conn.: Knight Ridder/Tribune Business News. Retrieved 24 April 2012.