St Mary Redcliffe

St Mary Redcliffe is an Anglican parish church located in the Redcliffe district of Bristol, England. The church is a short walk from Bristol Temple Meads station. The church building was constructed from the 12th to the 15th centuries, and it has been a place of Christian worship for over 900 years. The church is renowned for the beauty of its Gothic architecture and is classed as a Grade I listed building by Historic England.[1] It was famously described by Queen Elizabeth I as "the fairest, goodliest, and most famous parish church in England."[2][3]

| St Mary Redcliffe | |

|---|---|

St Mary Redcliffe from the north | |

St Mary Redcliffe | |

| 51.4482°N 2.5899°W | |

| Location | Redcliffe Way, Bristol, BS1 6NL |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Catholic Church |

| Churchmanship | Broad Church/Liberal Catholic |

| Website | Church website |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Parish church |

| Style | Perpendicular Gothic |

| Completed | 15th century |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 240 ft (73 m) |

| Width | 44 ft (13 m) |

| Nave width | 59 ft (18 m) |

| Height | 54 ft 9 in (16.69 m) |

| Spire height | 292 ft (89 m) |

| Administration | |

| Parish | St. Mary Redcliffe with Temple Bristol and St. John the Baptist, Bedminster |

| Deanery | Bristol South |

| Archdeaconry | Archdeaconry of Bristol |

| Diocese | Bristol |

| Province | Province of Canterbury |

| Clergy | |

| Vicar(s) | The Revd Canon Dan Tyndall The Revd Kat Campion-Spall (Associate Vicar) |

| Assistant priest(s) | The Revd Anthony Everitt |

| Honorary priest(s) | The Revd Peter Dill |

| Curate(s) | The Revd Aggy Palairet |

| Laity | |

| Organist/Director of music | Andrew Kirk |

| Organist(s) | Claire Alsop, Graham Alsop |

| Organ scholar | Matthew Brown |

| Churchwarden(s) | Elizabeth Shanahan, Richard Wallace |

| Verger | Matthew Buckmaster (Head Verger), Judith Reading, Anthony Scott, Paul Thomas |

| Business manager | Roseanna Wood |

| Youth ministry coordinator | Becky Macron |

| Music group(s) | The Choirs of St Mary Redcliffe |

Little remains of the earliest churches on the site although a little of the fabric has been dated to the 12th century. Much of the current building dates from the late 13th and 14th centuries when it was built and decorated by wealthy merchants of the city whose tomb and monuments decorate the church. The spire fell after being struck by lightning in 1446 and was not rebuilt until 1872. Little of the original stained glass remains following damage in the English Civil War with extensive new glass being added during the Victorian era. The tower contains 14 bells designed for full-circle English-Style change ringing. Other music in the church is provided by several choirs and the Harrison & Harrison organ.

History

The first church on this site was built in Saxon times, as the Port of Bristol first began.[4] In medieval times, St Mary Redcliffe, sitting on a red cliff above the River Avon, was a sign to seafarers, who would pray in it at their departure, and give thanks there upon their return. The church was built and beautified by Bristol's wealthy merchants, who paid to have masses sung for their souls and many of whom are commemorated there.[5]

Parts of the church date from the beginning of the 12th century. Although its plan dates from an earlier period, much of the church as it now stands was built between 1292 and 1370, with the south aisle and transept in the Decorated Gothic of the 13th century and the greater part of the building in the late 14th century Perpendicular. The patrons included Simon de Burton, Mayor of Bristol, and William I Canynges, merchant, five times Mayor of Bristol and three times MP. In the 15th century Canynges' grandson, the great merchant William II Canynges, also five times Mayor and three times MP, assumed responsibility for bringing the work of the interior to completion and filling the windows with stained glass. In 1446 much of this work was damaged when the spire was struck by lightning, and fell, causing damage to the interior; however the angle of the falling masonry and the extent of the damage is unclear.[6] Although the spire was to remain damaged for the next 400 years, Canynges continued in his commitment to restore and beautify the church. He took Holy Orders after the death of his wife, and is buried in the church.[7] Other families associated with St Mary Redcliffe include the Penns, the Cabots, the Jays, the Ameryks and the Medes.[5]

In 1571, the school that was to become St Mary Redcliffe and Temple School was formed in a chapel in the churchyard. The church and school have remained closely linked in many aspects of their operations.

The 17th century saw the loss of many of the church fittings and much of the stained glass during the Reformation and the English Civil War. During the reign of Queen Anne, and partially funded by her, the interior of St. Mary Redcliffe was refitted in the Baroque style.[8]

Thomas Chatterton, whose father was sexton of St Mary Redcliffe, was born in the house next to the church in 1752. He studied the church records in a room above the south porch, and wrote several works which he attempted to pass as genuine medieval documents. He committed suicide in London at the age of seventeen.[2] In 1795 the church saw the marriages of Samuel Taylor Coleridge to Sara Fricker and Robert Southey to Sara's sister Elizabeth.[9][10]

The upper part of the spire, missing since being struck by lightning in 1446,[11] was reconstructed in 1872 to a height of 292 ft (89 m).[2] Funds for the spire rebuilding had been raised by the Canynges Society, the Friends of St Mary Redcliffe, which was formed in 1843.[12] They raised most of the £40,000 needed.[13] The 1 tonne (0.98 long tons; 1.1 short tons) capstone was laid by the Mayor, Mr William Procter Baker, at the top of the scaffolding.[14][15] Because of the effect of environmental pollution on the Dundry Stone, further repairs to the spire and other stonework were needed in the 1930s.[15] A mobile telecommunication mast is fitted inside the spire.[16][17]

During the Bristol Blitz in the Second World War a bomb exploded in a nearby street, throwing a rail from the tramway over the houses and into the churchyard of St Mary Redcliffe, where it became embedded in the ground. The rail is left there as a monument.[18][19][20] An accompanying memorial plaque reads "On Good Friday 11th April this tramline was thrown over the adjoining houses by a high explosive bomb which fell on Redcliffe Hill. It is left to remind us how narrowly the church escaped destruction in the war 1939-45."[21]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 the church increased the number of its online streamed services, hosting the first fully online Easter service on its website and Facebook page. On August 29th 2020 St Mary Redcliffe, for the first time, broadcast a wedding online (of Sophia James and Mykhailo Melnykov) which was watched across The United States, Europe and Australia.

Archives

Parish records for St Mary Redcliffe church, Bristol are held at Bristol Archives (Ref. P.St MR) (online catalogue) including baptism, marriage and burial registers. The archive also includes records of the incumbent, churchwardens, overseers of the poor, parochial church council, chantries, charities, estates, restoration of the church, schools, societies and vestry plus deeds, photographs, maps and plans. Records related to St Mary Redcliffe are also held at Berkeley Castle in the Muniments Room and on microfilm at Gloucestershire Archives.[22]

Architecture and fittings

St Mary Redcliffe is one of the largest parish churches in England, and according to some sources it is the largest of all.[23][24] The spire is also the third tallest among parish churches,[25] and it is the tallest building in Bristol.[26]

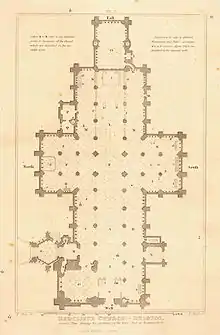

St Mary Redcliffe is cruciform in plan, with a chapel extending to the east of the chancel, and a large 13th-century tower placed asymmetrically to the north of the west front.[27] The tower was added to the building in the 13th century. It has broad angle buttresses and Y tracery to the windows. The bell stage has ogee gables and polygonal corner pinnacles. After the collapse of the original spire in 1446 it remained truncated until the 1870s when George Godwin rebuilt it.[28] The nave, chancel and choir are vaulted with richly decorated with bosses in a variety of styles. The Lady Chapel has a star vault. The transepts has large pointed spandrels and a blind arcade with mullions descending from the clerestory windows. Beneath the Lady Chapel is a small crypt, with a larger one beneath the transept of three by two bays.[28]

There is a rectangular 13th-century porch on either side of the nave.[5] The north porch has an inner component dating from 1200, with black Purbeck Marble columns, and an outer hexagonal portion built in 1325 which is ogee-cusped with a Moorish appearance.[2] The outer polygonal part of the north porch was built in the 14th century. It has crocketed gables to the buttresses and is richly decorated with pinnacles and a quatrefoil parapet above a lierne vault.[28]

Within the church are an oak chest with caryatids dating from 1593. The choir stalls date from the 15th century. There are two fonts; one from the 13th century and the other made of marble by William Paty was made in 1755. The oak pulpit was built in the 19th century by William Bennett. A wrought-iron gilded chancel screen built by William Edney in 1710 still stands under the tower.[1]

On 1 June 2016 Purcell announced they had been awarded the contract to extend St Mary Redcliffe to include visitor amenities, step-free access and a community hub.[29]

Monuments and memorials

The church is adorned with monuments to individuals from the history of the city, including Sir William Penn (the father of William Penn, founder of Pennsylvania). His helm and half-armour are hung on the wall, together with the tattered banners of the Dutch ships that he captured in battle. The church also displays a rib of a whale brought back from one of his voyages by John Cabot.[30]

The monuments of William II Canynges (c. 1399–1474) and his grandfather William I Canynges both have effigies on them, as do those of Robert de Berkeley[1] and of Philip Mede (c.1415-1475), a Member of Parliament and thrice Mayor of Bristol. Multiple mural monuments also exist in the church.[28] Amongst the monumental brasses is one to Richard Mede (d. circa 1488), son of Philip Mede.

Outside the churchyard set into the south end of a wall that runs along Redcliffe Hill is a brass drinking fountain dated 1832, with decorated with a lion's head.[31] This is the well head for St Mary's Conduit, and the end point of the traditional St Mary Redcliffe Pipe Walk, which is held in October every year.

Stained glass

Little of the early stained glass remains. In the west window of St John's Chapel, for instance, the medieval glass barely survived the destruction (said to have been caused by Oliver Cromwell's men).[32] Most of the higher portions went untouched, but others were severely damaged. In some cases the windows were impossible to repair, and clear glass was eventually introduced to replace the missing scenes. The Victorian stained-glass windows were created by some of the finest studios of that period.[33]

William Wailes produced a design for the seven-light east window following a competition launched in 1846; however, delays in raising the money caused delays in its installation. Controversy over the design meant that it was replaced with the current depiction of the Crucifixion by Clayton and Bell in 1904. The tree design in the window of the south transept was also by Wailes and was installed in 1854. In the north transept is a memorial window to Samuel Lucas who died in 1853, designed and installed by the St Helens Crown Glass Company which later became Pilkington. Another Wailes design depicting the Offering of the Wise Men was installed in the Lady Chapel, alongside one designed by Arthur O'Connor. The windows in the choir aisles are by Clayton and Bell who also designed the memorial to Edward Colston which is in the north wall of the north transept.[33] The stained glass window commemorating the 17th century Royal African Company magnate was removed in June 2020 following the toppling of the Statue of Edward Colston on 7 June, while the Diocese of Bristol announced a similar window in the city's Cathedral would also be removed.[34]

The west window was obscured by the organ until the 1860s when it was moved to make way for a depiction of the Annunciation which was designed by John Hardman Powell of Hardman & Co. and funded by Sholto Hare. Attempts to achieve some conformity with the installed work and subsequent designs lead to a further commissions for Clayton and Bell and Hardman & Co. generally as memorials to wealthy local dignitaries who had contributed to the restoration of the church.[33]

Hogarth's triptych

Sealing the Tomb, a great altarpiece triptych by William Hogarth, was commissioned in 1756 to fill the east end of the chancel. The churchwardens paid him £525 for his paintings of the three scenes depicted; the Ascension featuring Mary Magdalene,[35] on a central canvas which is 22 feet (6.7 m) by 19 feet (5.8 m). It is flanked by The Sealing of the Sepulchre and the Three Marys at the Tomb, each of which is 13 feet 10 inches (4.22 m) by 12 feet (3.7 m). They are mounted in gilded frames made by Thomas Paty.[36] This was removed from the church by mid-Victorian liturgists, before being displayed at the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery; it is now on display in the church of St Nicholas, Bristol.[2]

The church bells

The tower contains a total of 15 bells, one bell dating from as early as 1622 cast by Purdue and two cast by Thomas I Bilbie of the Bilbie family from Chew Stoke in 1763,[37] the remainder were cast by John Taylor & Co at various dates, 1903 (9 bells), 1951 (1 bell), 1969 (1 bell) and 2012 (1 bell). The larger Bilbie (10th) bell along with the 1622 Purdue (11th) bell are included in the 50 cwt ring of 12 bells.[38]

The bells are hung in a cast iron and steel H-frame by John Taylor & Co dating from the major overhaul of 1903.[39] A number of small modifications have taken place when each additional bell was added. The 50 cwt tenor bell is the largest bell in a parish church to be hung for full-circle English-Style change ringing and the 7th-largest such bell in the world, only surpassed by Liverpool Anglican Cathedral 11th (55 cwt), Wells Cathedral tenor (56 cwt), York Minster tenor (59 cwt), St Paul's Cathedral tenor, London (61 cwt), Exeter Cathedral tenor (72 cwt) and Liverpool Cathedral tenor (82 cwt).[40] A new 8th bell was cast by John Taylor & Co in 2012 for the Queen's Diamond Jubilee, replacing the 1768 Bilbie bell, a non-swinging bell with an internal hammer fitted for use as a service bell, and chimed from within the body of the church.[39][41]

The ring of 12 bells is augmented with two additional semitone bells. A sharp treble bell cast by John Taylor & Co in 1969 is the smallest bell in the tower and a "flat 6th" cast by John Taylor & Co in 1951 and allow different diatonic scales to be rung. All the bells have been tuned on a lathe; the tenor bell was tuned in 1903 and strikes the note of B (492 Hz).[42] The St Mary Redcliffe Guild of Change Ringers was founded in 1948.[43]

The clock chime can be heard striking the quarter chimes on the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 8th bells of the ring of 12 with the hours being struck on the largest 50 cwt (12th) tenor bell. The clock chime strikes the "Cambridge Chimes", commonly known as the "Westminster Chimes", every quarter of an hour daily from 7 am to 11 pm.[42] The chimes are disabled outside of these hours. If the bells are in the 'up' position, the chimes are also disabled (normally during the day on Sundays). The clock was fully converted to electric operation during the 1960s. It is now driven by a Smith's of Derby synchronous motor. The old pendulum, gravity escapement and weights, etc., were removed when the clock was automated. What remains of the clock movement and electrified chiming barrel is housed in a large enclosure in the ringing room. The clock face is approximately 3 m in diameter and is on the northern elevation.[42]

Choir

The choir have released numerous recordings, as well as touring Europe and North America.[44]

Organ

The first pipe organ in the church, built by Harris and Byfield in 1726, was of three manuals and 26 stops.[45] It was rebuilt in 1829 and again in 1867 on either side of the chancel.[45] In 1912 a four-manual, 71-stop organ having over 4,300 pipes was installed by Harrison & Harrison.[46] Towards the end of his life Arthur Harrison said that he regarded the organ at St Mary Redcliffe as his "finest and most characteristic work". The organ remains essentially as he designed it in 1911.[45]

Kevin Bowyer recorded Kaikhosru Sorabji's First Organ Symphony on it in 1988, for which the organ was an "ideal choice"; the notes to the recording describe the church as "acoustically ideal, with a reverberation period of 3½ seconds", and notes that the organ has "a luxuriousness of tone" and "a range of volume from practically inaudible to fiendishly loud".[47] William McVicker, organist at the Royal Festival Hall, has called the organ "the finest high-Romantic organ ever constructed".[48]

November 2010 saw the first performances on the organ after an 18-month renovation by its original builders Harrison & Harrison, costing around £800,000. The organ had been disassembled and some of it taken away to the builders' workshop in Durham.[49] The pipes were cleaned and the leather of the bellows was replaced.[45] The manuals were also fitted with an electronic panel for storing combinations of stop settings.[50]

Organists, choirmasters and directors of music

There is no record of the names of some of the early organists; however there is a record of several payments to Mr Nelme Rogers for playing the organ in the 1730s.[51] Rogers had a long tenure from 1727 when a new organ was installed until 1772, when John Allen took over.[52] Cornelius Bryan served as the organist from 1818 until 1840.[53] He was followed by Edwin Hobhouse Sircom until 1855 and then William Haydn Flood until 1862. For the next hundred years the post of organist was combined with that of choirmaster and was held by: Joseph William Lawson 1862–1906, Ralph Thompson Morgan 1906–1949, Kenneth Roy Long 1949–1952 and Ewart Garth Benson 1953–1968, who continued as the organist until 1987.[54]

From 1967 a choirmaster was appointed. The post was held by: Peter Fowler 1968, Bryan Anderson 1968–1980 and John Edward Marsh 1980–1987. From 1987 the title of the post was Director of Music and organist, with the post being held by: John Edward Marsh 1987–1994, Anthony John Pinel 1994–2003 and Andrew William Kirk since 2003.[54] The assistant organists have been: John Edward Marsh 1976–1980, Colin Hunt 1980–1990, Anthony John Pinel 1990–1994, Graham Alsop from 1990 and Claire Alsop from 2003.[54]

See also

References

- Historic England. "Church of St Mary Redcliffe (Grade I) (1218848)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Burrough 1970, pp. 13-14.

- Little 1967.

- "Your Visit — Heritage". St Mary Redcliffe. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- Jenkins 1999.

- "The Tower Vaulting — Archaeological Survey" (PDF). St Mary Redcliffe. Jerry Sampson Buildings Archaeology. 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "About Bristol – St. Mary Redcliffe".

- "18th century". St Mary Redcliffe. Archived from the original on 4 January 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- Cottle 2014, p. 189.

- Traill 2011, p. 20.

- "St Mary Redcliffe". About Bristol. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- "Restoration of St. Mary, Redcliffe". Bristol Mercury. 7 January 1843. p. 8. Retrieved 30 March 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Restoration of Redcliffe Church. Completion of the Spire". Western Daily Press. 1 May 1872. p. 3. Retrieved 30 March 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Restoration of Redcliffe Church. Laying the Cap-stone of the Spire". Bristol Mercury. 11 May 1872. p. 6. Retrieved 30 March 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Fells 2014, pp. 79-81.

- Combe, Victoria (30 November 2000). "Churches cash in on phone boom". Telegraph. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Kennedy, Maev (8 September 2000). "Angel heralds heaven-sent mobile solution". Guardian. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Memories of Bristol's Trams". Bristol history.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- Fells 2014, p. 115.

- "St Mary Redcliffe". About Bristol. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "ST MARY REDCLIFFE TRAM RAIL - War Memorials Online". www.warmemorialsonline.org.uk. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "National Archives catalogue, St Mary Redcliffe". Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Brackett 2008, p. 67.

- Ireland 1812, p. 148.

- "St Mary Redcliffe Church". Skyscraper News. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Redcliffe Character Appraisal" (PDF). Bristol City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Plan at Medieval Bristol – St. Mary's Redcliffe

- Foyle 2004, pp. 66-72.

- "Purcell announces win of St Mary Redcliffe extension contract". Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- Brace 1996.

- Historic England. "BALUSTRADE, WALL AND WELL HEAD 5 METRES WEST OF CHURCH OF ST MARY REDCLIFFE, City of Bristol (1202486)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "Cathedral and Church Repairs". Wessex Restoration. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Cobb, Peter G. (1994). "The Stained Glass of St. Mary Redcliffe, Bristol" (PDF). Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. 112: 143–166.

- "Church windows celebrating slave trader removed". BBC News. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Ogée, Bindman & Wagner 2001, p. 262.

- Fells, Maurice (2014). The A–Z of Curious Bristol. History Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0750956055.

- "Bristol, Redcliffe". Dove's Guide. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "The Bells of St Mary Redcliffe". St Mary Redcliffe. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Bristol church's 'clunking' bell to be fixed after 110 years". BBC. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Behind the scenes of Bristol's bellringing community". Bristol Post. 10 June 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Work Completed January — March 2013". John Taylor & Co. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "St Mary the Virgin, Redcliffe, Bristol". Lyndenlea. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "The Bells of St Mary Redcliffe" (PDF). St Mary Redcliffe. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Music / Recordings". St Mary Redcliffe. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Hale, Paul (November 2010). "Perfection Preserved The Harrison & Harrison organ in the church of St Mary, Redcliffe, Bristol" (PDF). Organists Review: 33–39.

- Aughton 2008, p. 127.

- "St. Mary Redcliffe Bristol Harrison & Harrison, 1912". Pleasures of the Pipes. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Aughton 2008, p. 154.

- Fells, Maurice; Harris, Dominic (6 November 2010). "'Masterpiece' church organ will play again". Bristol Evening Post. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- "Why cleaning Bristol St Mary Redcliffe's organ is like working on a 4,500-piece jigsaw". Bristol Evening Post. 10 March 2010. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- Carrington, Douglas R. "The Early History of the Organs" (PDF). St May Redcliffe. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Temperley & Banfield 2010, p. 145.

- Olleson 2003, p. 24.

- "Music Staff". St Mary Redcliffe. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

Bibliography

- Aughton, Peter (2008). St Mary Redcliffe: The Church and its People. Bristol: Redcliffe Press. ISBN 978-1-904537-83-0.

- Brace, Keith (1996). Portrait of Bristol. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7091-5435-6.

- Brackett, Virginia (2008). The Facts on File Companion to British Poetry: 17th and 18th Centuries. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9780816063284.

- Burrough, T.H.B (1970). Bristol (City Buildings Series). Studio Vista. ISBN 978-0289798041.

- Cottle, Joseph (2014). Reminiscences of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108079297.

- Fells, Maurice (2014). The A–Z of Curious Bristol. History Press. ISBN 978-0750956055.

- Foyle, Andrew (2004). Bristol (Pevsner Architectural Guides: City Guides). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300104424.

- Ireland, William Henry (1812). Neglected genius, a poem. London: W. Wilson. ISBN 978-5518572478.

- Jenkins, Simon (1999). Britain's Thousand Best Churches. The Penguin Press. ISBN 0-7139-9281-6.

- Little, Bryan (1967). The City and County of Bristol. Wakefield: S. R. Publishers. ISBN 0-85409-512-8.

- Ogée, Frédéric; Bindman, David; Wagner, Peter (2001). Hogarth: Representing Nature's Machines. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719059193.

- Olleson, Phillip (2003). Samuel Wesley: The Man and His Music. Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843830313.

- Temperley, Nicholas; Banfield, Stephen (2010). Music and the Wesleys. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252077678.

- Traill, Henry Duff (2011). Coleridge. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108034449.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Mary Redcliffe. |