Spermiogenesis

Spermiogenesis is the final stage of spermatogenesis, which sees the maturation of spermatids into mature spermatozoa. The spermatid is a more or less circular cell containing a nucleus, Golgi apparatus, centriole and mitochondria. All these components take part in forming the spermatozoon.

Phases

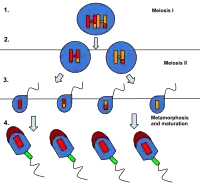

The process of spermiogenesis is traditionally divided into four stages: the Golgi phase, the cap phase, formation of tail, and the maturation stage.[1]

Golgi phase

The spermatids, which up until now have been mostly radially symmetrical, begin to develop polarity.

- The head forms at one end, and the Golgi apparatus creates enzymes that will become the acrosome.

- At the other end, it develops a thickened mid-piece, where the mitochondria gather and the distal centriole begins to form an axoneme.

Spermatid DNA also undergoes packaging, becoming highly condensed. The DNA is first packaged with specific nuclear basic proteins, which are subsequently replaced with protamines during spermatid elongation. The resultant tightly packed chromatin is transcriptionally inactive.

Cap/Acrosome phase

The Golgi apparatus surrounds the condensed nucleus, becoming the acrosomal cap.

Formation of Tail

One of the centrioles of the cell elongates to become the tail of the sperm. A temporary structure called the "manchette" assists in this elongation.

During this phase, the developing spermatozoa orient themselves so that their tails point towards the center of the lumen, away from the epithelium.

Maturation phase

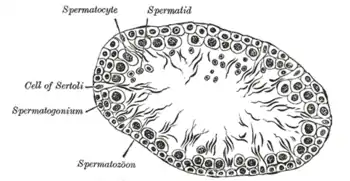

The excess cytoplasm, known as residual body of regaud, is phagocytosed by surrounding Sertoli cells in the testes.

Spermiation

The mature spermatozoa are released from the protective Sertoli cells into the lumen of the seminiferous tubule and a process called spermiation then takes place, which removes the remaining unnecessary cytoplasm and organelles.[2]

The resulting spermatozoa are now mature but lack motility, rendering them sterile. The non-motile spermatozoa are transported to the epididymis in testicular fluid secreted by the Sertoli cells, with the aid of peristaltic contraction.

Whilst in the epididymis, they acquire motility. However, transport of the mature spermatozoa through the remainder of the male reproductive system is achieved via muscle contraction rather than the spermatozoon's motility. A glycoprotein coat over the acrosome prevents the sperm from fertilizing the egg prior to traveling through the male and female reproductive tracts. Capacitation of the sperm by the enzymes FPP (fertilization promoting peptide, produced in the prostate gland) and heparin (in the female reproductive tract) removes this coat and allows sperm to bind to the egg.[3]

References

- ANAT D502 – Basic Histology

- O'Donnell, Liza; Nicholls, Peter K.; O'Bryan, Moira K.; McLachlan, Robert I.; Stanton, Peter G. (2011). "Spermiation". Spermatogenesis. 1 (1): 14–35. doi:10.4161/spmg.1.1.14525. PMC 3158646. PMID 21866274.

- Fraser, L. R. (September 1998). "Fertilization promoting peptide: an important regulator of sperm function in vivo?". Reviews of Reproduction. 3 (3): 151–154. doi:10.1530/ror.0.0030151. ISSN 1359-6004. PMID 9829549.

External links

- Swiss embryology (from UL, UB, and UF) cgametogen/spermato05

- Images and video of spermiogenesis - University of Arizona

- Overview at yale.edu