Sondra Locke

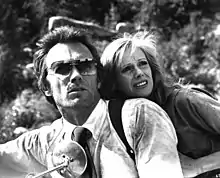

Sandra Louise Anderson (née Smith; May 28, 1944 – November 3, 2018), professionally known as Sondra Locke, was an American actress and director. She made her film debut in 1968 in The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, for which she was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. She went on to star in such hit films as Willard, The Outlaw Josey Wales, The Gauntlet, Every Which Way but Loose, Bronco Billy, Any Which Way You Can and Sudden Impact. She worked often with Clint Eastwood, who was her companion for 14 years. She also directed four films, notably Impulse. Locke's autobiography, The Good, the Bad, and the Very Ugly: A Hollywood Journey, was published in 1997.

Sondra Locke | |

|---|---|

Locke at a press conference in Burbank, July 1968 | |

| Born | Sandra Louise Smith May 28, 1944 Madison County, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | November 3, 2018 (aged 74) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Other names |

|

| Alma mater | Middle Tennessee State University |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1962–2016 |

| Spouse(s) | Gordon Anderson (m. 1967) |

| Partner(s) | Clint Eastwood (1975–1989) Scott Cunneen (1990–?) |

| Signature | |

| |

Background, early life and education

Sandra Louise Smith was born on May 28, 1944,[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] the daughter of New York City native Raymond Smith, then serving in the military,[lower-alpha 3] and Pauline Bayne, a pencil factory worker from Huntsville, Alabama, who was of mostly Scottish descent, with matrilineages in South Carolina dating back to the late 18th century.[28] Locke's parents separated before her birth.[29] In her autobiography, Locke noted that "although Momma would not admit it, I knew Mr. Smith never married my mother."[30] She had a maternal half-brother, Donald (born April 26, 1946) from Bayne's subsequent brief marriage to William B. Elkins.[31][lower-alpha 4] When Bayne married Alfred Locke in 1948, Sandra and Donald adopted his surname.[33][lower-alpha 5] She grew up in Shelbyville, Tennessee, where her stepfather owned a construction company;[34] the family later moved to nearby Wartrace.[35] Self-described as introspective[36] and ambitious,[37] Locke started working part-time at age 16, drove her own car, and had a telephone installed in her bedroom.[30]

Locke was a cheerleader and class valedictorian in junior high.[38] From 1958, she attended Shelbyville Central High School, where she was again valedictorian and voted "Duchess of Studiousness" by classmates.[39] She also played on the girls' basketball team, served as PTSA representative and was president of the French club.[19][20][21][22] (Regardless, she wasn't considered "date material" by the lotharios of her class.)[5] Following graduation in 1962, Locke enrolled at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro on a full scholarship.[30] Majoring in drama,[40] she was a member of the Alpha Psi Omega honor society while at MTSU and appeared onstage in Life with Father and The Crucible.[35][41][42] She dropped out after completing two semesters of study.[43]

In or around 1963,[44] Locke essentially broke off contact with her family, concluding: "It made no sense for any of us to spend our lives pretending to have relationships that did not really exist."[29] She never knew her biological father,[45] and did not attend the funerals of her mother (deceased 1997)[46] or stepfather (deceased 2007),[47] nor did she have anything to do with her brother, sister-in-law and three nieces.[25][39][48][lower-alpha 6] Donald blamed Gordon Anderson – Locke's best friend since adolescence and future husband – for the rift, claiming Anderson had "an almost hypnotic spell on her."[39]

Locke held a variety of jobs, including as a bookkeeper for Tyson Foods and secretary in a real-estate office.[30] For a time she lived in the commuter town of Gallatin.[50] In 1964, she joined the staff at radio station WSM-AM 650 in Nashville and was promoted to its television affiliate WSM-Channel 4 the following year.[39][51] Locke's biggest coup while employed there was interviewing actor Robert Loggia when Loggia visited Nashville to promote his TV pilot T.H.E. Cat, during which he "flirted outrageously" with Locke.[30] Locke also modeled for The Tennessean fashion page, acted in commercials, and gained further stage experience in productions for Circle Players Inc.[39][52] In 1966, the 22-year-old appeared in a UPI wire photo that showed her cavorting in new fallen snow.[53] Within one year of this exposure, she decided to pursue a career in film and changed the spelling of her first name to avoid being called Sandy.[52]

Career

Rise to prominence

In July 1967, Locke competed with 590 other Southern actresses and dozens of New York hopefuls for the part of Mick Kelly in a big-screen adaptation of Carson McCullers' novel The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter opposite Alan Arkin.[54][lower-alpha 7] For the first audition in Birmingham, then-fiancé Gordon Anderson gave his bride a so-called Hollywood makeover: he bound her bosom,[56] bleached her eyebrows[30] and carefully fixed her hair, makeup and outfit so as to create a more gamine appearance.[57] They also lied about her age, shaving off six years to seem younger[58][lower-alpha 8] – a pretense Locke would keep up for the rest of her career.[lower-alpha 9] After callbacks in New Orleans and Manhattan, she was cast in the role.[54]

The film came out in the summer of 1968 to critical acclaim.[66] Locke's performance garnered her an Academy Award nomination, as well as a pair of Golden Globe nominations for Best Supporting Actress and Most Promising Newcomer.[67][68][lower-alpha 10] She also won "Most Promising New Star of the Year" at the Show-A-Rama film exhibitor convention.[lower-alpha 11] Although her salary for the film was reported in newspapers as $15,000, Locke later claimed it was less than one-third that amount.[30]

Commercial ups and downs, missed roles, TV work

Hoping to shed the Plain Jane image she accentuated in her screen debut, in January 1969 Locke posed for a semi-nude pictorial by photographer Frank Bez,[70] which was published in the December issue of Playboy.[71] The Playboy layout established Locke's status as a sex symbol, and the images were recycled in other men's magazines as her fame increased. Nearly three decades later, Locke said she still got those photos in fan mail for her autograph.[30]

Her next role was as Melisse in Cover Me Babe (1970), originally titled Run Shadow Run,[72] opposite Robert Forster. She made it as part of a $150,000 three-picture deal with 20th Century Fox, and was compensated for the other two which never came to fruition.[73][74] It was announced that she would play the lead in Lovemakers – a film adaptation of Robert Nathan's novel The Color of Evening – but no movie resulted.[75][76] Locke was offered Barbara Hershey's role in Last Summer (1969), but her agent turned it down without telling her.[77] Shortly afterwards she passed on the lead in My Sweet Charlie (1970), which won an Emmy for its eventual star Patty Duke.[78]

In 1971, Locke co-starred with Bruce Davison and Ernest Borgnine in the psychological thriller Willard, which became a surprise box office smash.[79] Locke felt overqualified for her role but did it as a favor to Davison,[64] who at the time was her unofficial paramour.[80][81] She was then featured in William A. Fraker's underseen mystery A Reflection of Fear (1972) and held the title role in The Second Coming of Suzanne (1974), winner of three gold medals at the Atlanta Film Festival.[82] Both films were shelved for two years before finally opening in arthouse cinemas, attracting little attention at first. Over time Suzanne has developed a cult following,[30][64] while Reflection is cited as an early example of media portrayals of transgender people.[83][lower-alpha 12]

In 1973, Locke was attached to star in Terminal Circle. "It's a woman's role that comes along once in a lifetime," she said.[85] The San Francisco-set drama was to be directed by Mal Karman and shot by cinematographer Robert Primes, who did camerawork for Gimme Shelter, but it was scrapped for lack of funds.[85] She was up for a big part in Earthquake (1974), but lost out to Geneviève Bujold.[86]

Locke guested on top-rated television drama series throughout the first half of the 1970s, including The F.B.I., Cannon, Barnaby Jones and Kung Fu. She was advised by her agents to stay away from TV, but thought it silly to sit around not working between films.[87] In the 1972 Night Gallery episode "A Feast of Blood",[88] she played the victim of a curse planted by Norman Lloyd; the recipient of a brooch that devoured her. Lloyd acted with Locke again in Gondola (1973), a racially themed, three-character teleplay co-starring Bo Hopkins, and commended the actress for "a beautiful performance – perhaps her best ever."[89] Ron Harper, who worked with Locke on the short-lived 1974 show Planet of the Apes, was even more effusive: "After acting with her in a couple of scenes, there was something so feminine about her that I could picture myself easily falling for her ... She's one of those women who exudes femininity, and you just become so attracted to that."[90]

Films with Clint Eastwood

In 1975, Locke was cast in The Outlaw Josey Wales as the love interest of Clint Eastwood's eponymous character.[91] Locke said she chose the role for its exposure,[92] following a run of unremarkable credits.[93] She took a pay cut just to be in the film; her salary for Josey Wales was $18,000 – less than half of what she'd earned for her previous job.[94] The film was one of the top 15 grossing films of 1976 and revived Locke's career.[95][96][97] She followed it up with a lead role alongside Eastwood in the popular action film The Gauntlet (1977), the duo replacing Steve McQueen and Barbra Streisand, who bowed out from the production due to a reported clash of egos.[98] Its pre-publicity touted Locke as "the first actress ever to be in a Clint Eastwood movie and get equal billing on screen with the macho star."[99] Eastwood unblushingly predicted that she would win an Oscar for her performance.[100] Locke wasn't even nominated and received mixed critical response at best: on the upside, Vincent Canby of The New York Times said "Locke is not only pretty, but also occasionally genuinely funny"[101] and Los Angeles Times critic Kevin Thomas stated that Locke "has not received such a rich opportunity since her Academy Award-nominated debut";[102] in contrast, Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune said "she's wasted here"[103] and TV Guide felt that "Locke is simply repulsive."[104]

Over the course of their decade-and-a-half-long personal relationship, Locke did not work in any capacity on any theatrical motion picture other than with Eastwood except for 1977's experimental horror western The Shadow of Chikara.[105] The home invasion film Death Game (1977), though released after they became an item, was actually shot in 1974.[106] "Clint wanted me to work only with him," said Locke.[30] "He didn't like the idea of me being away from him."[107]

In 1978, Locke and Eastwood appeared with an orangutan named Manis in that year's fourth highest-grossing film, Every Which Way but Loose.[108] She portrayed country singer Lynn Halsey-Taylor in the adventure-comedy. Its 1980 sequel Any Which Way You Can – for which Locke earned a six-figure salary plus a share of the profits[94] – was nearly as successful.[109] She recorded several songs for the soundtracks of these films and was whispered to be shopping for a record deal at the time. Honing her musical skills, Locke performed live in concert (one-off gigs) with The Everly Brothers, Eddie Rabbitt and Tom Jones.[110]

During this period, Eastwood did a few movies that had no prominent female character for Locke to play. In the meantime, she accepted some television offers, co-starring with an all-female ensemble cast in Friendships, Secrets and Lies (1979) and portraying Big band era vocalist Rosemary Clooney in Rosie: The Rosemary Clooney Story (1982).[111] While the biopic followed Clooney from age 17 to 40, Locke was 38 when she played the role.

Locke starred as a bitter heiress who joins a traveling Wild West show in Bronco Billy (1980), her only film with Eastwood not to reach blockbuster status, though it still ranked among the annual box office top 25.[109] The New York Times critic Janet Maslin noticed that "each of them works more delicately here than they have together previously."[112][lower-alpha 13] Locke cited Bronco Billy and The Outlaw Josey Wales as her favorites of the movies they made.[114] The couple's final collaboration as performers was Sudden Impact (1983), the highest-grossing film in the Dirty Harry franchise,[115] in which Locke played an artist with her own code of vigilante justice.[lower-alpha 14][lower-alpha 15] Her fee was a reported $350,000.[94]

Locke never appeared in a wide release after Sudden Impact.[117] The film premiered five months before her 40th birthday, the customary cutoff age for leading ladies of the era. Locke announced plans to develop and star in a movie about Marie Antoinette, but the project fell apart.[118] Eastwood then directed Locke in a 1985 Amazing Stories episode entitled "Vanessa in the Garden".

Directing

In 1986, Locke made her feature directorial debut with Ratboy, a fable about a youth who is half-rat, produced by Eastwood's company Malpaso.[119] When asked why she'd been absent from her longtime beau's recent star vehicles, Locke replied simply, "I wasn't right for the roles."[120][lower-alpha 16] Ratboy had limited distribution in the United States, where it was a critical and financial flop, but was well-received in Europe, with French newspaper Le Parisien calling it the highlight of the Deauville Film Festival.[121]

Locke's second foray behind the camera was Impulse (1990), starring Theresa Russell as a police officer on the vice squad who goes undercover as a prostitute. Siskel & Ebert gave the film "two thumbs up".[122] In a subsequent interview with Siskel, Locke said she wasn't eager to act again. "If you love the craft of filmmaking as much as I do, it's hard to go back to acting after you've tasted the high of directing."[7]

After a long interruption in her career due to personal and legal difficulties, Locke directed the made-for-television film Death in Small Doses (1995), based on a true story, and the independent feature Trading Favors (1997), starring Rosanna Arquette.

Memoir and final projects

In 1997, Locke's autobiography The Good, the Bad, and the Very Ugly: A Hollywood Journey was published by William Morrow and Company. In it she called Eastwood "a completely evil, manipulating, lying excuse for a man."[30] Eastwood's lawyers sent a warning letter to the publisher, and although no slander charges arose, Entertainment Tonight canceled a scheduled interview with Locke.[123] She was also bumped from The Oprah Winfrey Show and, in her words, "shut out of most venues to promote the book, in particular the networks."[124] The book received a rave and supportive review from New York Daily News writer Liz Smith,[125] while Entertainment Weekly's Dana Kennedy dismissed the book as a "peculiar, not terribly consequential, life story."[126]

Locke told a Spanish website that she'd been informed Entertainment Weekly originally planned to publish a positive review, but for reasons unclear, it was pulled and a negative review appeared instead.[124] The Advocate, a monthly LGBT-interest magazine, was set to do a big article on Locke's book; suddenly and uncharacteristically, Eastwood gave The Advocate an interview, and they decided not to run both pieces.[124] She reflected in 2012: "Clint has said so many bad things about me to the media since we split up, and he has so much more access and power to do that. He's said things that were hurtful to my character and hurtful to me professionally."[127] Locke was nonetheless grateful to have a platform at all, stating: "It was a miracle that a major publisher took it."[124]

After 13 years away from acting, Locke returned to the screen in 1999 with small roles in the straight-to-video films The Prophet's Game with Dennis Hopper and Clean and Narrow with Wings Hauser. In 2014, the media announced that Locke would serve as an executive producer on the Eli Roth film Knock Knock, starring Keanu Reeves.[128] She came out of retirement once more in 2016, shooting Alan Rudolph's indie Ray Meets Helen with Keith Carradine.[129] The film was screened at Laemmle Music Hall on May 6, 2018, less than six months before Locke died.[130]

Philanthropy

During her tenure at WSM, Locke participated in the annual United Cerebral Palsy (UCP) telethons. One year, she toured Birmingham with folk singer Richard Law.[131]

In 1992, Locke served as honorary chairwoman for the "Starry, Starry Night" silent auction in Costa Mesa, California to benefit Human Options, a shelter for victims of domestic violence. "Being a woman I have great empathy for these women. I can understand how stranded they must feel, how hard it is to change one's life," Locke said.[132]

Personal life

Mixed-orientation marriage

On September 25, 1967,[56] Locke married sculptor Gordon Leigh Anderson[lower-alpha 17] (born August 2, 1944, Batesville, Arkansas) at the First Presbyterian Church in Nashville,[139] one week after The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter commenced principal photography.[54] She had known Anderson since 1956, when they met in seventh grade at Shelbyville Mills School.[lower-alpha 18] In early 1969, as Locke was flooded with script offers after her Oscar nomination, she and Anderson left Tennessee and moved into a condo at The Andalusia in West Hollywood.[30]

According to a 1989 affidavit, the marriage was "tantamount to sister and brother" and they never consummated it.[141] Anderson is openly gay.[142][143][144][145] Locke, testifying under oath to a jury, characterized her husband as being "more like a sister to me" and explained, "it's funny the sort of cultural changes, but in those days males and females never lived together unless they were married."[146] According to her death certificate, the two were still legally married when she died,[lower-alpha 19] and he was the person who reported her death.[148]

Anderson is front and center in Locke's autobiography, but she doesn't elaborate on her reasons for marrying him beyond the following passage:

However conventional or unconventional our marriage might turn out to be honestly did not concern me that much. I was very young, but I had come to feel that, for me, sex was the least important element in a relationship and the one thing that time had proven to me was that my love for Gordon came from such a deeply connected place that it transcended everything else.[30]

Dalliances

Given that Locke waited decades to confirm that her marriage was platonic, most of her actual romantic attachments went unpublicized. In the mid-1960s, she dated her supervisor at WSM-TV's PR department, Brad Crandall (1920–1973).[149][150][151] Former colleagues at the station insinuated posthumously that Locke was promoted to the department through nepotism.[149] She started as secretary to Tom Griscom in local sales for WSM Radio.[149][152]

George Crook, a cameraman for WSM, squired Locke to Nashville society events including the 1965 hunt ball.[153][154] He later got into local politics and was elected mayor of Belle Meade in 2000.[155] Locke was also rumored to have dated co-stars Bruce Davison (Willard), Paul Sand (The Second Coming of Suzanne) and Bo Hopkins (Gondola), as well as producer Hawk Koch and John F. Kennedy's nephew Robert Shriver.[80][156][157] For a while in the early 1970s, she shared a non-exclusive liaison with married actor David Soul after they played siblings in an episode of Cannon.[158]

Locke alluded to these intervals as "casually exploring for a romantic relationship," noting that she had not fallen in love with any of the men. "Love ... was not something to search out actively; it finds you, I believed."[30]

Life with Eastwood

Locke and actor/director Clint Eastwood entered a domestic partnership in October 1975.[38] She first met Eastwood in 1972 when she unsuccessfully lobbied for the title role in his film Breezy (1973);[159] they became involved upon arrival at the shooting location of The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) in Page, Arizona.[45] "It was just an immediate attraction between the two of us," Locke recalled in a 2012 documentary.[127] She revealed that they made love on their first date "several times. It was truly magic. Together, it seemed that, though we were two bodies, two hearts . . . in perfect accord we were one."[160] Locke had simultaneously been wooed by screenwriter Philip Kaufman but chose Eastwood over him.[113][lower-alpha 20] After wrapping the film in December 1975, the couple shuttled between Eastwood's houses in Sherman Oaks and Carmel, as well as rented homes in San Francisco and Tiburon.[94] They eventually settled at 846 Stradella Road in Bel-Air,[38] which Eastwood still owns.[163]

Eastwood was married during the first several years of their relationship,[164][165] before their affair became public in 1978,[38] but if anything his marriage was as big a sham as Locke's: he'd sired at least two publicly unacknowledged children outside the marriage[94][166][167][168] and confided he'd "never been in love before."[169] Locke claimed Eastwood even sang "She Made Me Monogamous" to her.[164][169][170] Eastwood's wife Maggie Johnson lived on a colossal estate in Pebble Beach, where Eastwood rarely stayed,[30] and he and Johnson were understood to have had an open marriage from the start.[171] "I never knew I could love somebody so much, and feel so peaceful about it at the same time," Locke said he told her.[30] Conversely, the media's running narrative was that Eastwood "left"[142] or "walked out on"[157] his wife for Locke as opposed to simply giving up the facade. Locke resented being labeled as an affair and made to feel sleazy as if she'd "stolen" a married man, but did not refute it.[30]

Late in the 1970s, Locke became pregnant by Eastwood twice;[94] she aborted both pregnancies.[172][lower-alpha 21] "I'd feel sorry for any child that had me for a mother," she previously told columnist Dick Kleiner in 1969.[175] In 1979, at the age of 35, Locke underwent a tubal ligation at UCLA Medical Center, citing Eastwood's adamancy that parenthood would not fit into their lifestyle.[30] When this became public knowledge a decade after the fact, Eastwood issued a statement:

I adamantly deny and deeply resent the accusation that either one of those abortions or the tubal ligation were done at my demand, request or even suggestion. As to the abortions, I told Locke that whether to have children or terminate her pregnancies was a decision entirely hers. Particularly with regard to the tubal ligation, I encouraged Locke to make her own decision after she had consulted with a physician about the appropriateness of and the necessity for that surgical procedure.[27][176]

Locke professed mixed feelings on the matter, stating in one chapter of her autobiography that she was grateful she hadn't had Eastwood's children, while writing in another, "I couldn't help but think that that baby, with both Clint's and my best qualities, would be extraordinary."[30] Eastwood claimed Locke told him on multiple occasions that she never wanted to have children.[177]

Eastwood and Locke were still cohabiting when, in the latter half of the 1980s, he secretly fathered another woman's two children[178][179] – a fact that did not come to light for almost 20 years.[lower-alpha 22] Despite her affirmed ignorance, Locke sensed growing tension in the relationship around 1985, recollecting that "although I definitely still loved Clint, I didn't very much like him."[30] In retrospect, she gathered "either he changed from white to black, or I had been living with somebody I didn't even know."[127]

Palimony suit

According to court testimony, Locke confronted Eastwood over his passive-aggressive behavior on December 29, 1988,[lower-alpha 23] eliciting estrangement between the couple.[29][38] Locke testified that after she and Eastwood made their final public appearance on January 6 at the American Cinema Awards, they spent exactly two nights together,[157] without intimate contact.[94] Eastwood then effectively vacated their Bel-Air mansion, sleeping in the adjacent gardener's quarters or at his apartment in Burbank.[94] Locke thought Eastwood was acting out "because he wasn't number one at the box-office anymore, or because he was facing his mortality."[94] (Eastwood was 58 at the time.) As far as she was concerned their relationship was still salvageable.[183] At any rate, she called divorce lawyer Norman Oberstein to explore her options should the separation be permanent. Unbeknownst to Locke, Eastwood eavesdropped on these consultations by means of a wiretap that he placed on their home phone in early March.[94][113][123]

On the morning of April 3[176] or 4,[94] Eastwood complained in the kitchen that Locke was "sitting on [his] only real estate in Los Angeles" and bolted.[30] Locke later defensively declared: "Clint is not good at direct communication. He really is a man of few words. You might just as well have a direct confrontation with a wall."[184] On April 10, 1989, Malpaso employees changed the locks on the family residence, moved Locke's possessions into storage, and posted security guards at the front gate per Eastwood's order.[94] Locke was shooting Impulse (1990) at the time of the lockout;[124] she filed a $70 million palimony suit on April 26,[94][113] charging Eastwood with breach of contract, emotional distress, forcible entry and possession of stolen goods.[185] Forced abortions and compulsory sterilization were also cited, though Locke would later reclass those operations as a "mutual decision."[94]

During their 14 years as husband and wife de facto, Locke and Eastwood had inhabited seven homes and acquired four, including a spacious retreat in Sun Valley, Idaho and the Rising River Ranch in Burney.[186][187] Locke sought half of Eastwood's earnings and an equal division of property,[188] requesting title to the house in Bel-Air and to the Gothic style West Hollywood place Eastwood had leased to Gordon Anderson since 1982.[38] She also asked Judge Dana Senit Henry to bar Eastwood from the Bel-Air house "because I know him to have a terrible temper ... and he has frequently been abusive to me."[189]

Locke battled Eastwood in court for 19 months; she developed breast cancer during the proceedings and said the treatments sapped her will to fight.[164] In November 1990, the parties reached a private settlement wherein Eastwood set up a $1.5 million, multi-year film development/directing pact for Locke at Warner Bros. in exchange for dropping the suit.[107] She got the West Hollywood property (valued at $2.2 million), $450,000 cash and unspecified monthly support payments as well.[176] Eastwood kept their pet parrot Putty and renamed him Paco.[94]

The breakup affected Locke's social life. Her closest friends had been the wives of Eastwood's colleagues: Maria Shriver, Cynthia Sikes Yorkin and Lili Fini Zanuck, all 10–11 years younger than Locke and married to industry heavyweights Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bud Yorkin and Richard D. Zanuck respectively.[94] Locke's friendships with these women gradually became nonexistent as their husbands ghosted her.[123] The female comrades Locke credited with loyalty and support were those she'd known pre-Eastwood: art director Elayne Barbara Ceder, whom she met on The Second Coming of Suzanne, and realtor Denise Fraker, wife of A Reflection of Fear director William A. Fraker.[30]

Fraud suit

Between 1990 and 1993, Warner Bros. rejected more than 30 scripts that Locke pitched to the studio – including those for Junior (1994) and Addicted to Love (1997) – and refused to let her direct any of their in-house projects.[190][191][192] When her contract had yielded zero directing assignments three years in, Locke became convinced the deal was a sham.[193] She began to seek corroboration and came across incriminating printouts from WB's bookkeeping records.[94] Locke contended that the money WB pretended they were paying her came from Eastwood's pocket and was laundered through the operating budget of Unforgiven (1992).[30][64] In June 1995 she sued him again, for fraud and breach of fiduciary duty.[194][195] According to Locke's attorney Peggy Garrity, Eastwood committed "the ultimate betrayal" by arranging the "bogus" deal as a way to keep her out of work.[196] Garrity added that Eastwood had held out the allegedly counterfeit deal "like a dangled carrot" to persuade Locke to drop the earlier palimony suit.[196] Locke said that she "was stunned and outraged at the way I had been tricked and cheated a second time."[30]

The case went to trial in September 1996.[197] One juror disclosed that the panel sided with Locke by a 10-to-2 vote (nine votes are needed for a verdict) and were only debating the amount.[198] Before any court decision could be made, Locke settled the case with Eastwood for an undisclosed amount of money.[198] The outcome, Locke said, sent a "loud and clear" message to Hollywood, "that people cannot get away with whatever they want to just because they're powerful."[199] According to Locke, "in this business, people get so accustomed to being abused, they just accept the abuse and say, 'Well, that's just the way it is.' Well, it isn't."[38]

For his part, Eastwood waved the lawsuit off as a "dime-novel plot,"[198] continuing, "it's all about money ... about getting something for nothing."[200] He accused Locke of using her cancer to gain the jury's sympathy: "She plays the victim very well. Unfortunately she had cancer and so she plays that card."[201]

Locke brought a separate action against Warner Bros. for allegedly conspiring with Eastwood to sabotage her directorial career.[202] As had happened with the previous lawsuit, this ended in an out-of-court settlement, in May 1999.[203] By then, Locke had fired Garrity and hired Neil Papiano to represent her.[204][lower-alpha 24] The agreement with Warner Bros., Locke said, was "a happy ending."[206] "I feel elated. This has been the best day in a long, long time," Locke said outside the courthouse.[207] The case is used in some modern law-school contract textbooks to illustrate the legal concept of good faith.[208]

Illness; last relationship

A lifelong nonsmoker (save for a few film roles),[209] Locke practiced Transcendental Meditation[210] and worked out with weights, though she hated running.[211] In September 1990, she confirmed reports that she had breast cancer.[212] "Due to factors in my personal life, I have sustained two years of extreme and unnecessary stress, which my doctors tell me has been my enemy," Locke said at the time.[212] She added that Eastwood never communicated with her after her diagnosis: "He doesn't care if I live or die."[184][213]

Locke underwent a double mastectomy at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, followed by chemotherapy.[27] During treatment, she began dating Scott Cunneen (born September 10, 1961, Long Beach, California), an intern assigned to perform the post-surgical checkup.[63][113][123][214][215] Unfazed by their 17-year age difference – and the fact Locke was only three years younger than his mother[216] – they soon went public with the romance, dining at paparazzi hotspot Spago on one of their early dates in November 1990.[217] Cunneen moved in with her in the spring of 1991.[30] She called it a "real, supportive, and equal relationship."[30]

In February 2001, Locke purchased a six-bedroom gated mansion in the Hollywood Hills, where she resided for the remainder of her life.[218] Built in 1925, the home's interior was redesigned to look like Locke's old house on Stradella Road.[127] She and Cunneen eventually broke up, albeit without publicity, since she had faded from public view.[lower-alpha 25]

In 2015, after a 25-year period of apparent remission,[220] Locke's cancer returned and metastasized to her bones.[18]

Death

Locke died at age 74 on November 3, 2018, at her L.A. home, from cardiac arrest related to breast and bone cancers.[221][222][223][224] Her remains were cremated on November 9, at Pierce Brothers Westwood Village Memorial Park and Mortuary and the ashes were given to her widower, Gordon Anderson.[18]

Locke's death was not publicized until December 13, the day before her ex's latest blockbuster The Mule (2018) opened in theaters nationwide. The Associated Press said "it is not clear why it took nearly six weeks to come to light."[148] According to the AP report, attempts to reach Anderson for comment were unsuccessful.[148] Locke left Anderson an estimated fortune of $20 million, and seemed to have always supported him financially.[126]

Legacy

Locke is remembered as an early pioneer for women in Hollywood.[225] She was one of 11 female filmmakers in 1990, the year WB released her sophomore feature, Impulse.[226] By the time of Trading Favors (1997), her fourth effort, still only eight percent of all films were made by women, per the Directors Guild of America.[226]

Locke's influence as a feminist icon was duly acknowledged by the mainstream press. In 1989, Claudia Puig of the Los Angeles Times described her lawsuit against Clint Eastwood as a "precedent-setting legal case, as it raises the question of whether a woman, who is legally married to one man, can claim palimony rights from another."[105] Childfree by choice – unusual for a person of her generation[227] – Locke was among the first celebrities to publicly discuss her abortion experiences.[172] The disclosure made Locke "a talking-point in America's sexual politics debate," according to The Guardian's Peter Bradshaw.[142] Locke's subsequent relationship with a doctor young enough to be her son added to her notoriety.[228]

During the last third of her life, Locke maintained she was blacklisted from the film industry as a result of her acrimonious split from Eastwood;[64] his career moved forward unscathed.[38] Peggy Garrity, Locke's former counsel, recalled the courtroom drama in her book In the Game: The Highs and Lows of a Trailblazing Trial Lawyer (2016). Garrity revealed that Locke's 1999 confidential settlement from WB "was for many millions more than the settlement with Clint had been."[205] Locke v. Warner Bros. Inc also catalyzed changes within the legal system. In a landmark decision,[229] California's Supreme Court ruled that access to civil trials could no longer be closed off to the public.[230][231]

Other actresses admire Locke as someone who merited respect on the strength of her directorial accomplishments, however short-lived. Frances Fisher, who dated and had a child by Eastwood in the 1990s, applauded her predecessor for "her courageous battle with the cancerous patriarchal power structure in our industry."[232] Rosanna Arquette commented that Locke "had laser vision" and "was great with actors," adding, "It is horrible to be blackballed."[233]

Numerous outlets faced pushback over their chosen headlines for Locke's obituary. In what was deemed a sexist epitaph,[225][234][235] virtually every major publication prefaced news of her death by tagging Eastwood's name atop the article.[228] Fans on social media were quick to point out that Locke was an Oscar nominee before she even met him. Women's blog Jezebel criticized The Hollywood Reporter for depicting Locke as a nonentity;[236] THR subsequently changed its headline.[225] News organization TheWrap – whose editor, Sharon Waxman, reviewed Locke's memoir for The Washington Post in 1997 – opined that her story "should stir resonance in this age of the #MeToo movement."[225] In a tribute to the late actress, author Sarah Weinman wrote: "Sondra Locke, like Barbara Loden, deserves to be known for her work, not for the famous man she was disastrously involved with."[225]

Our Very Own

In 1971, fifth-graders at Eastside Elementary in Locke's hometown of Shelbyville, Tennessee were left star-struck when Locke made a visit and held pretend "auditions" in the class to show them what it was like in Hollywood.[40] One student, Cameron Watson, was inspired by Locke and is now an actor/director. Watson's period drama Our Very Own (2005) takes place in Shelbyville in 1978 and focuses on a group of teenagers who want to meet Locke when she returns to town for the local premiere of Every Which Way but Loose. Watson decided to do the movie after performing a standup routine about Locke and about how people in Shelbyville were obsessed with her.[237] Locke attended one of those performances in 2004 at the Tiffany Theater in West Hollywood. "The minute she heard the first reference to her or to her family, she threw up her arms: 'What the hell is this?'" Watson said. "By the end of the reading, she was doubled over."[238] Locke gave the script her blessing and accepted an invitation to be special guest at the film's premiere.[239] The movie was a "special gift" to Locke, according to Deborah Obenchain, another Eastside student who said she did not think Locke really understood her impact on the small town she once called home. "I think it meant just as much to her. … In our own way … we got to live out a little bit of our dreams by making the movie and meeting her."[40]

Filmography

As actress

| Year | Title | Role | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter | Margaret 'Mick' Kelly | Nominated—Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress Nominated—Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture Nominated—Golden Globe Award for Most Promising Newcomer — Female Nominated—Laurel Award for Female Supporting Performance Nominated—Laurel Award for Female New Face |

[240] |

| 1970 | Cover Me Babe | Melisse | [241] | |

| 1971 | Willard | Joan | [242] | |

| 1972 | A Reflection of Fear | Marguerite | [242] | |

| 1972 | Night Gallery | Sheila Gray | Episode: "A Feast of Blood" | [243] |

| 1972 | The F.B.I. | Regina Mason | Episode: "Dark Christmas" | [222] |

| 1973 | Cannon | Trish | Episode: "Death of a Stone Seahorse" | [222] |

| 1973 | The ABC Afternoon Playbreak | Nora Sells | Episode: "My Secret Mother" | [222] |

| 1973 | Gondola | Jackie | TV movie | [222] |

| 1974 | The Second Coming of Suzanne | Suzanne | [222] | |

| 1974 | Kung Fu | Gwyneth Jenkins | Episode: "This Valley of Terror" | [222] |

| 1974 | Planet of the Apes | Amy | Episode: "The Cure" | [222] |

| 1975 | Barnaby Jones | Alicia | Episode: "The Orchid Killer" | [222] |

| 1975 | Cannon | Stacey Murdock | Episode: "A Touch of Venom" | [222] |

| 1976 | Joe Forrester | N/A | Episode: "A Game of Love" | [222] |

| 1976 | The Outlaw Josey Wales | Laura Lee | [222] | |

| 1977 | Death Game | Agatha Jackson | [222] | |

| 1977 | The Shadow of Chikara | Drusilla Wilcox | [244] | |

| 1977 | The Gauntlet | Augustina 'Gus' Mally | [142] | |

| 1978 | Every Which Way but Loose | Lynn Halsey-Taylor | [245] | |

| 1979 | Friendships, Secrets and Lies | Jessie Dunne | TV movie | [246] |

| 1980 | Bronco Billy | Antoinette Lily | Nominated—Razzie Award for Worst Actress | [247] |

| 1980 | Any Which Way You Can | Lynn Halsey-Taylor | [248] | |

| 1982 | Rosie: The Rosemary Clooney Story | Rosemary Clooney | TV movie | [248] |

| 1983 | Sudden Impact | Jennifer Spencer | [248] | |

| 1984 | Tales of the Unexpected | Edna | Episode: "Bird of Prey" | [248] |

| 1985 | Amazing Stories | Vanessa Sullivan | Episode: "Vanessa in the Garden" | [248] |

| 1986 | Ratboy | Nikki Morrison | Also director Nominated—Razzie Award for Worst Actress |

[249] |

| 1999 | The Prophet's Game | Adele Highsmith (adult) | [250] | |

| 1999 | Clean and Narrow | Betsy Brand | [250] | |

| 2018 | Ray Meets Helen | Helen | Final film role | [251] |

Stage

| Year | Show | Role | Location | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Life with Father | Mary Wickes | Tucker Theater, Murfreesboro, Tennessee | [35] |

| 1963 | The Crucible | Mary Warren | Tucker Theater, Murfreesboro, Tennessee | [41] |

| 1964 | Life with Mother | N/A | Belcourt Playhouse, Nashville, Tennessee | [256] |

| 1964 | The Innocents | Flora | Circle Theater, Nashville, Tennessee | [257] |

| 1964 | A Thousand Clowns | Dr. Sandra Markowitz | Circle Theater, Nashville, Tennessee | [258] |

| 1965 | Night of the Iguana | Charlotte Goodall | Circle Theater, Nashville, Tennessee | [133] |

| 1965 | Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma's Hung You in the Closet and I'm Feelin' So Sad | Rosalie | Circle Theater, Nashville, Tennessee | [134] |

| 1965 | The Glass Menagerie | Laura Wingfield | Circle Theater, Nashville, Tennessee | [135] |

| 1967 | Tiger at the Gates | Helen of Troy | Vanderbilt Theatre, Nashville, Tennessee | [259] |

Footnotes

- During her Hollywood heyday, various dates were given by the press for Locke's birth. Contradictory sources have either directly cited, or implied, every year from 1943 to 1950,[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8] and some of the more ludicrous PR gimmicks in the 1970s purported it to be as late as 1952[9][10][11] or 1956.[12][13] Her most commonly reported year of birth was 1947; Locke's publicist gave that year on several occasions when asked to clarify the discrepancies.[14][15][16] However, Locke's marriage license,[17] death certificate,[18] yearbooks,[19][20][21][22] and her entry on public records indexes Ancestry.com,[17] FamilySearch[23] and Intelius[24] establish the year undoubtedly as 1944. "Untruths have been a way of life for her," one former associate wrote to the Shelbyville Times-Gazette when the disparity came up.[25] Said another past acquaintance who knew Locke in the 1950s: "She was two years younger than me in Central High, but it is really strange now, because she has now become five years younger."[25]

- Sources are divided as to whether she was born in Alabama or Tennessee.[26] Locke said the latter.[27]

- Smith may have died before Locke learned of him. The actress wrote in her autobiography that she found out he was her father "sometime during grammar school," but phrased all references to him in ambiguous past tense and was evasive when it came to specifying years (as confessing her age would've altered her persona and her whole public relations narrative). If one reads between the lines, it becomes ostensible that Locke's father was killed during World War II.

- Bayne was also wed to painter Thomas H. Nelson between marriages to William Elkins and Alfred Locke, for less than eight months.[32]

- In 1945, Locke briefly took the surname of her then-stepfather, Elkins, before her mother changed it again in 1948. Her legal name was changed four times during her first 24 years of life: from Sandra Smith to Sandra Elkins, to Sandra Locke, to Sondra Locke, to Sondra Anderson.

- Notwithstanding their ongoing estrangement, Bayne vocally supported her daughter during the litigious war between Locke and Clint Eastwood. She told journalist Leon Wagener: "One of those children Clint made her abort could have been the grandson I've always wanted."[49]

- After-the-fact publicity claimed that 2,000 actresses tried out for the role.[55]

- Bonnie Bedelia told the 8 October 1967 Los Angeles Times that "they decided I was too old" when she auditioned for the same role as Locke.[59] As it turns out, Bedelia was four years younger than Locke, who had lied about her age. Wayne Smith, a UA student five years Locke's junior[60] played her love interest in the movie, even though his character is described as being a couple years older than she.

- In the 1960s, The Billings Gazette[61] and The Nashville Tennessean[62] outed Locke for lying about her age, but it took decades for syndicated publications to catch on, and most sources would continue to use the incorrect birth year(s).[63] Locke admitted in The Good, the Bad, and the Very Ugly that she lied about her age early in her career, but claimed to have knocked only three years off, rather than six. In one of her final interviews, conducted in 2015 for The Projection Booth podcast, Locke said that she "was just graduating high school" when she made The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter when she was in fact in her mid-20s.[64] In addition to the lie about her age, an international press release from 1967 omits Locke's time at MTSU as well as her residence in Nashville, where she had moved in 1963 after dropping out of college.[62][65]

- Even though Locke played the leading female role, Warner Bros.-Seven Arts campaigned for Best Supporting Actress instead of Best Actress during awards season, seemingly to make winning easier. She lost to Ruth Gordon for Rosemary's Baby. Ruth Gordon would later appear with Locke in Every Which Way but Loose and Any Which Way You Can.

- Locke's plaque was stolen at Mid-Continent International Airport.[69]

- A Reflection of Fear was not the first time Locke was considered to play a transsexual. In 1969, Christine Jorgensen, the Bronx man who became a woman in 1953 after surgery and medical treatment in Denmark, mentioned Locke and Mia Farrow as contenders for a planned film version of her life. A fan of Locke's performance in The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, Jorgensen observed that "in scenes where she didn't wear any makeup, Sondra looks very much like I did in my younger days. I think she might make an excellent choice."[84]

- It's probably relevant that Bronco Billy was made at a crossroads in the couple's life. Filming occurred in autumn 1979, shortly after Locke took permanent measures to avoid motherhood by undergoing sterilization – a choice Locke said she was reluctant to make. "Her relationship with Clint never fully recovered from the abortions," writes biographer Marc Eliot.[113]

- It has not gone unnoticed that four of the six Eastwood/Locke movies—The Outlaw Josey Wales, The Gauntlet, Bronco Billy, Sudden Impact—show Locke's character being sexually assaulted, and that their only onscreen teamings void of a token attempted rape scene—Every Which Way but Loose, Any Which Way You Can—happen to be the two Eastwood didn't also direct. Moreover, only Sudden Impact has a plotline that calls for such a scene; the rest are just randomly there. This pattern is never addressed in Locke's autobiography or in Richard Schickel's volumes of Eastwood-devoted works.

- Furthermore, 24 of the 47 films Eastwood has starred in during his five decades as a top-billed star depict violence against women. If you also count those he directed but didn't star in, he's made 17 films in which a female character is killed, 12 films depicting rape or attempt to rape, and 11 films showing a female character physically battered. This is particularly juxtaposing given Eastwood's self-proclamation as a "feminist filmmaker."[116]

- Locke's autobiography provides a convoluted recollection of the casting process for City Heat (1984). Blake Edwards was originally slated to direct the film; Edwards promised Locke one of the two female leads at a stage in development when Burt Reynolds had signed on but the role of the other leading man was yet to be filled. Locke asserted that Edwards was merely using her to lure in her superstar boyfriend—who'd seen the script and turned it down—because once Eastwood came on board, Edwards stopped talking to Locke and cast Madeleine Kahn in the role she'd been eyeing. Edwards ultimately withdrew and was replaced by Richard Benjamin. Nevertheless, Eastwood disappointed Locke by not using his clout to get her in the movie.

- Gordon Anderson went by the stage names 'C.B. Anderson'[133][134][135] and 'Gordon Addison'[136][137][138] during a brief acting career before he married Locke.

- In magazine interviews, Locke and Anderson would variously claim to have met when they were 10,[34] 11[56] or 12.[140] Anderson, like his late wife, always lied about his age, thus contributing to the inconsistency.

- For a long time it was falsely presumed that Locke and Anderson had divorced.[147]

- Philip Kaufman started to direct Josey, but was fired at Eastwood's command on October 24, 1975, three weeks into filming.[94][161] Although Eastwood had conquered Locke within 48 hours of her arrival on set, initially she had declined his advances, having already said yes to a date with Kaufman at the costume fitting.[30] According to biographer Patrick McGilligan, Eastwood begrudged the fact that a younger man had beaten him to the punch and therefore felt inclined to assert his dominance by getting rid of Kaufman.[94] The love triangle resulted in the Director's Guild passing new legislation, known as 'the Eastwood Rule', which prohibits an actor or producer from firing the director and then becoming the director himself.[162]

- Locke explained in her autobiography: "Before I had met Clint my gynecologist had suggested and fitted for me an IUD. Because my sex life was not very active, he did not think I should be constantly taking birth control pills. Clint complained of the IUD – it was uncomfortable for him, he said. And he too was not in favor of birth control pills, so he suggested a special clinic at Cedars Hospital where they taught a 'natural' method of birth control. It was the same 'rhythm' system that historically has been used to determine the fertile days for those who are attempting to achieve pregnancy. Of course, it could be used for the opposite results as well. Not only was I taught their method but I was constantly monitored with regular pregnancy checks. The whole process was awkward and entailed taking my temperature every morning and marking the calendar, etc. It was demanding and ultimately it had failed twice."[173][174]

- Although the existence of Eastwood's offspring by Jacelyn Reeves was reported in tabloids such as Star[180] and in Locke's autobiography during the 1990s, it continued to be ignored by reputable media sources until about 2006.[181] As late as 2003, for instance, A&E produced a two-hour, authorized Biography episode on Eastwood which gave the false impression he had a mere total of four children,[182] when he in fact has at least eight.[168][179]

- Eastwood's passive-aggressive gestures toward Locke included inviting Jane Brolin – a woman he was having an affair with – to join Locke and himself on their annual ski trip to Sun Valley. The two women got into a row just before New Year's Eve, Locke recalling, "I wanted to hit her, to pull every hair out of her head."[30]

- In June 1999, Garrity sued Locke to get paid for persuading the appellate court to reinstate Locke v. Warner Bros. Inc.[204] WB had requested summary judgement after the original March 1994 filing, which the court granted, but in August 1997 the decision was reversed.[113] Garrity put 2,500 hours of work into the case, only to be dumped by Locke and replaced by Papiano in May 1998.[204] Garrity won her lawsuit, and remarked that the payment would not have cost Locke a dime more than what was already going to legal fees, since it would simply have come out of Papiano's one-third contingency fee.[205]

- The exact year of this breakup is not known with certainty. The Notable Names Database, an infamously flawed source, cites 2001.[63] Seeing the split was never formally announced, the said timeframe might be an approximation inferred from Locke's real estate transactions, as the L.A. Times reported she offloaded one of her properties that year.[219]

See also

References

- Miranda C. Herbert, Barbara McNeil (1985). Biography and Genealogy Master Index, Volumes 1-5. Gale Research Company. ISBN 0810315068.

- Roberts, Jerry (2009). Encyclopedia of Television Film Directors. Scarecrow Press. p. 345. ISBN 978-0810863781.

- Editors of Chase's Calendar of Events (2011). Chases Calendar of Events, 2012 Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 287. ISBN 978-0071766739.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Film Actors, Volume 5. Hollywood Creative Directory (Firm), IFilm Publishing, 2002

- Sondra Locke opens door to fame Marjory Adams, The Boston Globe, August 27, 1968

- Clint, Sondra Loom As Big New Team Earl Wilson, Fort Lauderdale News, December 1, 1977

- Siskel, Gene (May 6, 1990). "Sondra Locke's Step". Chicago Tribune.

- Locke Exercises Control Over ‘Ratboy,’ Her Career Nancy Mills, Los Angeles Times, August 19, 1986

- The Charlotte News, 3.24.79

- Austin American-Statesman, 3.25.79

- The Boston Globe, 4.22.79

- Barbara Lewis, The Salina Journal, 8.8.76

- Scranton Tribune, 8.14.76

- Slaughter, Sylvia (May 28, 1989). "Sondra vs. Clint in palimony suit". The Tennessean.

Don Locke loves his sister. He misses her, and he regrets the fact that his three daughters don't have any knowledge of Sondra other than what they see on TV or in print or hear from gossipmongers. 'Sondra's not this kind of bad character,' he says. 'Maybe she's changed, but she was my big sister who used to play baseball with me. Sondra's gonna be 45 May 28 ...' Locke's publicist claims Sondra will be 42 today.

- "One Way to Gain Stardom". Terry Kay, The Atlanta Constitution, June 6, 1971

- Sondra's a Nice Girl, Despite What Studio Says Dayton Daily News, August 10, 1968

- "Gordon Leigh Anderson, Sondra Louise Locke". Tennessee State Marriages, 1780-2002. Ancestry.com.

Date: 9-25-67; Name of Female Applicant: Sondra Louise Locke; Born: 5-28-44; Age: 23

- Trock, Gary; Walters, Liz (December 15, 2018). "Clint Eastwood's Longtime GF, Sondra Locke Died from Cardiac Arrest". The Blast.

- 1959 Shelbyville Central High School Yearbook Classmates.com

- 1960 Shelbyville Central High School Yearbook Classmates.com

- 1961 Shelbyville Central High School Yearbook Classmates.com

- 1962 Central High School Yearbook Classmates.com

- Sondra L Anderson, "United States Public Records, 1970-2009" FamilySearch.org

- Sondra L Anderson, Phone Number, Address & Background Info Intelius

- Melson, David (May 23, 2012). "Picturing the Past 160: Sondra Locke on TV". Times-Gazette.

- Obituary: Sondra Locke, actress known for her troubled association with Clint Eastwood Brian Pendreigh, HeraldScotland, 16 December 2018

- Thompson, Douglas (2005). Clint Eastwood: Billion Dollar Man. John Blake. ISBN 1857825721.

- Various compilers, "Vaughn Family Group Sheets", Jim Freeman received these Family Group Sheets at a Bell family reunion for descendants of David Vaughn.

- Furtado, David (August 31, 2013). "Sondra Locke's The Good, the Bad, and the Very Ugly: The Woman with a Name". Wand'rin' Star.

- Locke, Sondra (1997). The Good, the Bad, and the Very Ugly: A Hollywood Journey. William Morrow and Company. ISBN 068815462X.

- Madison County, Alabama Brides - Page 29

- Pauline Bayne, "Alabama County Marriages, 1809-1950" FamilySearch.org

- WALKER COUNTY, GA - VITAL RECORDS MARRIAGES

- Armstrong, Lois. "Taking Up The Gauntlet". People, February 13, 1978.

- "MTSC Presents". The Daily News Journal. November 2, 1962. p. 7.

- Sondra Relates to True Self Lydia Lane, Los Angeles Times, January 3, 1971

- Sondra un-Lockes Film Golden Gates Dick Kleiner, Philadelphia Daily News, October 9, 1968

- James Robert Parish (2006). The Hollywood Book of Breakups. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 1630262080.

- "Sondra vs. Clint in palimony suit". The Tennessean. May 28, 1989.

- DeGennaro, Nancy. "Oscar-nominated actress, Tennessee native Sondra Locke dies at 74". December 14, 2018.

- "The Crucible Next College Production". The Daily News Journal. February 24, 1963. p. 15.

- "Sondra Locke in The Crucible: MTSU theater production, 1963". Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- Pendergrass, Tony. Sondra Locke to return via cinema. Sidelines. February 12, 1971. p. 3.

- Johnstone, Iain (1981). The Man with No Name: Clint Eastwood. Plexus. ISBN 978-0859650267.

- "Sondra Locke, Oscar-Nominated Actress for 'The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter,' Dies at 74". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- The Tennessean, 6.14.97

- Obituary: Alfred Taylor Locke (11/30/07) Shelbyville Times-Gazette

- "When Harry Left Sondra". People. August 7, 1989.

- Pauline Locke interviewed by Leon Wagener, 1989

- Hinton, Elmer. Down to Earth. The Nashville Tennessean. June 30, 1965. p. 9.

- Oscar-nominated actress, Channel 4 alumna Sondra Locke dead at 74 WSMV.com, December 13, 2018

- Haun, Harry (August 30, 1968). "Sandra of Shelbyville Becomes Sondra of the Cinema". The Tennessean.

- "Snow Hits Tennessee". The Daily Times-News. November 3, 1966. p. 1.

- Hieronymus, Clara (August 15, 1967). "Nashville Actress Gets Starring Movie Role". The Nashville Tennessean.

- Loftus, Linda (August 10, 1968). "Meeting Sondra Locke Was Groovy!". The Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Peer J. Oppenheimer (November 24, 1968). Sondra Locke– They Call Her 'The Beautiful Fake' : A selfless husband with a flair for fooling catapulted this shy officeworker to overnight stardom. Sarasota Herald-Tribune

- New face in the movie world Chicago Tribune, August 12, 1968. Vol. 122, Iss. 225, Section 2, p. 6

- Sondra Locke obituary The Times, December 15, 2018

- Smith, Cecil (October 8, 1967). "Bonnie's Westward Stage Trek". Los Angeles Times.

- Hale, Wanda (July 28, 1968). "Screen McCullers Novel". New York Daily News.

- "People Etc". The Billings Gazette. May 25, 1969.

Sweet little Sondra is actually 25 years old and married. Because of the movie, people think she's about 13, so she's now considering offers to do a nude layout for a magazine to prove she's no kid, and pave the way for adult roles.

- Hieronymus, Clara (December 24, 1967). "Nashvillians in the Times". The Tennessean.

The spelling of her name has been changed to "Sondra," her age lowered to 17 years for publicity purposes, and her residence in Nashville, where she was employed by WSM, wiped out.

- Sondra Locke Notable Names Database

- White, Mike (January 16, 2016). "Special Report: Death Game / Knock Knock". The Projection Booth (Podcast). Interviews with Larry Spiegel, Sondra Locke, and David Worth.

- Cinderella Story Of Young Actress Montreal Gazette, September 19, 1967

- Sondra Takes a Film by Storm. The Sydney Morning Herald, August 4, 1968

- "Winners & Nominees: Best Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role in any Motion Picture 1969". GoldenGlobes.com. Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- "Oscar Ceremony 1969 (Actress In A Supporting Role)". Oscars.org. Academy Awards. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- Carroll, Harrison (March 12, 1969). "Behind the Scenes in Hollywood". The Advocate-Messenger.

- Times Leader, 4.1.69

- "Sex Stars of 1969'". Arthur Knight and Hollis Alpert, Playboy, Vol. 16, Iss. 12

- Harold Heffernan (August 14, 1969). Sondra Valuable Behind the Scene. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- "May 28, 1944 Sondra Locke was born". FilmmakerIQ.com. May 28, 2019.

- Greenberg, Abe (June 11, 1969). "Hard Work vs. Jinx, or The Luck of Sondra Locke". Valley Times.

- "Sondra Set for 'Lovemakers'". Los Angeles Times. March 3, 1969. p. 72.

- Lansing State Journal, 1.11.70

- Mell, Eila (2013). Casting Might-Have-Beens: A Film by Film Directory of Actors Considered for Roles Given to Others. McFarland & Company. p. 142. ISBN 978-1476609768.

- Haun, Harry (May 16, 1971). "Charade for Hollywood". The Tennessean.

- Norma Lee Browning (August 4, 1971). What Makes a Box Office Hit?. Bangor Daily News.

- (Podcast) Willard (1971) — Episode 53— Decades of Horror 1970s Gruesome Magazine, June 26, 2017

- Bruce Davison, DVD audio commentary, 2017, Shout! Factory

- Canadian Society of Cinematographers, Cinema Canada, Issues 12-17, 1974

- Gambin, Lee (February 15, 2016). "Exclusive Interview: Actress Sondra Locke on Gender-Bender Chiller A REFLECTION OF FEAR". ComingSoon.net.

- Philadelphia Daily News, 5.28.69

- "The Actress Couldn't Resist". Jeanne Miller, San Francisco Examiner, August 30, 1973.

- "2,500 Movies Challenge". www.dvdinfatuation.com.

- Actress says TV creates automatons Will Jones, Star Tribune, December 3, 1972

- "Rod Serling's Night Gallery: the Second Season; A Feast of Blood (NIGHT GALLERY #22 - original air date January 12, 1972)". NightGallery.net. Universal Television. 2018.

- Lloyd, Norman (1990). Stages: Norman Lloyd. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810822903.

- Weaver, Tom (2009). I Talked with a Zombie: Interviews with 23 Veterans of Horror and Sci-Fi Films and Television. McFarland. p. 154. ISBN 978-0786452682.

- "Eastwood co-star set". Lansing State Journal, October 28, 1975

- "A long time between breaks". Jeanne Miller, San Francisco Examiner, July 1, 1976

- "Career Off to Great Start, and Then...". Stanley Eichelbaum, San Francisco Examiner, November 3, 1972

- Patrick McGilligan (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. HarperCollins. ISBN 000255528X.

- Top 1976 Movies at the Domestic Box Office The Numbers

- Sondra Locke | Biography, Movie Highlights and Photos Hal Erickson, AllMovie

- "Locke Is Big With Eastwood". Vernon Scott, Lebanon Daily News, December 20, 1977

- "Eastwood getting a lock on Locke". Earl Wilson, Independent Press-Telegram, April 17, 1977

- Pat O'Haire, New York Daily News, 11.11.77

- Earl Wilson, Fort Lauderdale News, 11.16.77

- Screen: Eastwood 'Gauntlet' Vincent Canby, The New York Times, December 22, 1977

- Thomas, Kevin (December 21, 1977). "'The Gauntlet' Lives Up to Its Title". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 15.

- Siskel, Gene (December 22, 1977). "Lots of bullets fly, but 'Gauntlet' is full of blanks". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 5.

- The Gauntlet - Movie Reviews and Movie Ratings TV Guide

- Puig, Claudia (May 8, 1989). "In the Matter of Locke vs. Eastwood". Articles.latimes.com.

- Anderson, George (October 21, 1974). "Local Angle". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Block Communications. p. 12. ISSN 1068-624X.

- Errico, Marcus (September 11, 1996). "Eastwood's Ex-Lover Says He Torpedoed Her Career". E! News.

- Top 1978 Movies at the Domestic Box Office The Numbers.

- 1980 Yearly Box Office Results Box Office Mojo

- Aaron Gold, Chicago Tribune, 2.1.79

- "Locke Steps Into Big Band Era Role". Dick Kleiner, The Daily Advertiser, July 28, 1982

- Eastwood Stars and Directs 'Bronco Billy' Janet Maslin, The New York Times, June 11, 1980

- Eliot, Marc (2009). American Rebel: The Life of Clint Eastwood. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0307336897.

- Parke, Henry C. (December 15, 2015). "Outlaw Josey Wales – Forty Years Later". Henry's Western Round-up.

- "Dirty Harry Movies". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- "Clint Eastwood—America's Major Feminist Filmmaker". Roger Ebert, San Francisco Examiner, July 18, 1984

- "Sondra Locke - Box Office". The Numbers.

- Lumenick, Lou (June 3, 2008). "DVD Extra: New 'Dirty Harry' Set Showcases … Sondra Locke". New York Post.

- "Sondra Locke tries other side of the camera". The Greenville News, September 28, 1985

- "Locke Turns To 'Ratboy' To Escape Clint's Maze". Roderick Mann, Los Angeles Times, March 23, 1986

- 'Ratboy': Snared In The Studio Trap. Pat. H. Broeske, Los Angeles Times. February 15, 1987.

- Siskel and Ebert 1990 Ratings list

- Waxman, Sharon (November 20, 1997). "Make Her Day". The Washington Post.

- Furtado, David (October 19, 2013). "Exclusive Interview with Sondra Locke: Magic in films and the real world". Wand'rin' Star.

- "Struggling Locke strikes back at Eastwood". Liz Smith, The Baltimore Sun, October 22, 1997

- Kennedy, Dana (October 31, 1997). "Book Review: 'The Good, the Bad and the Very Ugly'". Entertainment Weekly.

- L'album secret de Clint Eastwood. Dir. Pierre Maraval, 2012

- Kay, Jeremy (April 28, 2014). "Voltage taking Eli Roth's Knock Knock with Keanu Reeves to Cannes". ScreenDaily. Cannes.

- Onofri, Adrienne (June 3, 2016). "BWW Interview: Keith Carradine on the New Encores! Cast Album of PAINT YOUR WAGON". BroadwayWorld.

- Alan Rudolph, Keith Carradine, Sondra Locke and Jennifer Tilly in Person at the Music Hall for RAY MEETS HELEN. May 3, 2018

- Feenotes.com: Richard Law

- "For Human Options, the Light Is Bright". Los Angeles Times, December 16, 1992

- "'All Pure Pleasure,' Veteran Of Theater Flight Reports". The Nashville Tennessean. September 19, 1965.

- "Theater To Hold Tryouts". The Nashville Tennessean. October 17, 1965.

- "'Menagerie' Opens". The Nashville Tennessean. November 21, 1965.

- Gordon Addison Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Gordon Addison Broadway and Theatre Credits Broadway World

- Glover, William (June 25, 1966). "6 Characters in Search of Theme". Oakland Tribune.

- "Ask Showcase". The Nashville Tennessean. November 2, 1975.

- Look, 4.2.68

- "Locke Married?". The Palm Beach Post. May 9, 1989.

- Bradshaw, Peter (December 14, 2018). "Sondra Locke: a charismatic performer defined by a toxic relationship with Clint Eastwood". The Guardian. London. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- "Biography: Sondra Locke - TCM". Tcm.com.

- "Eastwood's Ex Tells All in Unflattering New Book. Peggy Deans Earle, The Virginian-Pilot, November 26, 1997

- A Fond Farewell to Sondra Locke (1944 – 2018) Harrison, John (December 16, 2018). Filmink.

- O'Neill, Ann W. (September 16, 1996). "Eastwood Unforgiven: Locke's Lawsuit Spins Saga of Love and Power in Hollywood". Retrieved December 14, 2018 – via LA Times.

- New York Daily News, 8.5.84

- Dalton, Andrew (December 13, 2018). "Oscar-nominated actress Sondra Locke dies at 74". AP news.

- Alan Nelson - The Associated Press has reported that... | Facebook

- The Official Tennessee Radio Hall Of Fame Community Public Group | Facebook

- "Videotapers' Syndication $$ Whopper for Nashville". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 79 (14): 40. April 8, 1967.

- The Nashville Tennessean, 1.25.64

- "Hunt Ball To Climax Weekend". The Nashville Tennessean. May 7, 1965.

- "Federation Dance Tonight". The Nashville Tennessean. December 15, 1965.

- Whitehouse, Ken (November 1, 2012). "Ex-Belle Meade mayor passes away". NashvillePost.com.

- Walter Scott's Personality Parade. October 15, 1989.

- Kaufman, Joanne; Savaiano, Jacqueline (May 15, 1989). "Suing Clint Eastwood, Sondra Locke Strikes with Magnum Force". People.

- Joyce Haber (1972-11-08). "Locke, Soul Set for Cannon Roles". Los Angeles Times.

- O'Brien, Daniel (1996). Clint Eastwood: Film-Maker. London: B. T. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-7839-X.

- Locke's book tells `The Good, the Bad and the Very Ugly' Deseret News, January 5, 1998.

- "Clint Eastwood gets top role in outlaw film". Greeley Daily Tribune. July 7, 1975. p. 24.

- Eastwood Rule Hollywood Lexicon

- Dillon, Nancy (February 22, 2013). "Clint Eastwood is the latest celebrity to fall victim to 'swatting'". New York Daily News.

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly Young, Josh (May 4, 1997). The Independent.

- "Eastwood won't wed girlfriend". The San Bernardino County Sun, September 8, 1979

- Kerrigan, Mike; Williams, Brian (July 11, 1989). "Clint's Bombshell Secret – He Has Illegitimate Daughter & Grandson". National Enquirer.

- Clint Eastwood Appears in Public With His Secret Daughter for the First Time Inside Edition (December 14, 2018)

- Bergen, Spencer. "The wild story of Clint Eastwood's eight children". Page Six December 27, 2018.

- Miller, Victoria. "Sondra Locke & Clint Eastwood: Inside Their Rocky Hollywood Romance". Inquisitr, December 14, 2018.

- Radner, Hilary (2017). The New Woman's Film: Femme-centric Movies for Smart Chicks. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1317286486.

- Eden, Barbara (2011). Jeannie Out of the Bottle. Crown Archetype. ISBN 978-0307886958.

- "Hollywood love affair with abortions topic of 'The Choices We Made'". Catholic Sentinel. April 4, 1991.

- Women speak out about celebrities they say coerced them to have abortions Cassy Fiano-Chesser, Live Action, December 30, 2018

- Sondra Locke dies at 74: The real story behind her relationship with Clint Eastwood Priyam Chhetri, MEAWW, December 14, 2018

- The Times and Democrat. Orangeburg, South Carolina. July 29, 1969. p. 9

- Schickel, Richard (1996). Clint Eastwood: A Biography. Random House. ISBN 0679749918.

- "Sandra Locke bitter, shocked about split with Clint Eastwood". Hartford Courant, May 18, 1989

- Fuster, Jeremy (December 13, 2018). "Sondra Locke, Oscar-Nominated Actress and Longtime Clint Eastwood Partner, Dies at 74". TheWrap.

- Leonard, Tom (January 31, 2019). "Is photo of Clint Eastwood's 8 children 'blended family harmony' or cruel abandonment?".

- Viens, Stephen (February 27, 1990). "Clint Eastwood's Secret 4-Year Love Comes Out of Hiding". Star.

- The Reeves children are not included in the count, for instance, at Helligar, Jeremy (January 13, 1997). "Passages". People.

News anchor Dina Ruiz, 31, more than made husband Clint Eastwood's day when she gave birth to the couple's first child, an 8-lb. 4-oz. girl named Morgan, on Dec. 12 in Los Angeles. This is the 66-year-old actor-director's fifth child....

- "Behind the Scenes with Clint". Dallas Morning News. October 4, 2003.

- Hamilton, Anita. "Celebrating Seniors - Clint Eastwood Turns 85 - Politics and Passion". June 3, 2015.

- Hall, Allan. "Clint v Sondra for a Fistful of Dollars". Daily Record, September 12, 1996.

- Eastwood's private life stranger than fiction Jeanne Wright, The San Bernardino County Sun, June 2, 1989

- Eastwood buys ranch Inter Mountain News, November 30, 1978

- 102 Wedeln Ln, Sun Valley, ID 83353 Zillow

- "She Won't Be Locked Out". Hank Gallo, New York Daily News, April 5, 1990

- "Eastwood's Ex Hit Hard by Sudden Impact of Breakup". St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 24, 1989.

- "Sondra Locke continues to battle ex-beau Clint Eastwood". Josh Young, Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 26, 1995

- The Triumph and Tragedy of Sondra Locke Yohana Desta, Vanity Fair, December 14, 2018

- "Eastwood Undermined Locke’s Directing Career, Attorney Says". Steve Ryfle, Los Angeles Times, September 12, 1996

- "Locke cries foul at producing deal". Liz Smith, The Palm Beach Post, April 30, 1994

- "Eastwood is target of another Locke Lawsuit". Chicago Tribune, June 7, 1995

- "Locke Says She Was 'Humiliated'". Los Angeles Times, September 13, 1996

- "Eastwood, ex-lover settle court battle as jurors deliberate". Daily News. September 25, 1996.

- O'Neill, Ann W. (September 18, 1996). "Sondra Locke Suing Clint Eastwood". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- Errico, Marcus (September 24, 1996). "Clint Eastwood Pays Off Sondra Locke". E! News.

- "Eastwood Settles with Sondra Locke". Philadelphia Inquirer. September 25, 1996. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- Eastwood Settles Fraud Suit With Ex-Lover Locke Efrain Hernandez Jr., Ann W. O'Neill, Los Angeles Times, September 25, 1996

- "Clint Eastwood - Interview - Western Movie Star". Bernard Weinraub, Playboy, March 1997

- O'Neill, Ann W. (May 23, 1999). "Settlement Could Make Locke's Day". Los Angeles Times.

- Ryan, Joal (May 25, 1999). "Vindication for Clint Eastwood's Ex-Lover". E! News.

- This Time, Judge Judy's a Defendant Ann W. O'Neill, Los Angeles Times, June 6, 1999

- Garrity, Peggy (2016). In the Game: The Highs and Lows of a Trailblazing Trial Lawyer. She Writes Press. ISBN 978-1631521065.

- The Battle's Over for Eastwood's Ex . People, July 5, 1999

- Huffaker, Donna. "Eastwood's ex settles with Warner Bros". Los Angeles Daily News.

- Crystal, Nathan; Knapp, Charles; Prince, Harry, eds. (2007). Problems in Contract Law: Cases and Materials (6th ed.). New York City: Aspen Publishing. pp. 470–80. ISBN 978-0735598225.

- Interview with Leta Powell Drake. KOLN/KGIN-TV (Lincoln, NE). 1982.

- "Sondra Locke: A match for the macho Clint Eastwood". Bart Mills, Chicago Tribune, June 25, 1978

- Sondra Locke and her career as sidekick Chris Chase, The New York Times, December 23, 1983

- "Sick-bay report". The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 20, 1990

- Sondra Locke Clipping Magazine photo orig 1pg 8x10 M7797 at Amazon's Entertainment Collectibles Store

- "Swingers and Roundabouts". Film Review. Orpheus Pub. June 1991.

- "Locke Biography" Archived July 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. annoline.com. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- "Mary Ann Forman, Born 01/19/1941 in California". www.californiabirthindex.org.

- Actress Sondra Locke and boyfriend Scott Cunneen on November 10, 1990... News Photo Getty Images

- "Sondra Locke's House". virtualglobetrotting.com. February 25, 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- Ruth Ryon, Los Angeles Times, 12.16.01

- Squires, Bethy (December 13, 2018). "Sondra Locke, Girlfriend Turned Enemy of Clint Eastwood, Is Dead". Vulture.

- Jacob, Mary (December 13, 2018). "Clint Eastwood's Longtime Partner Sondra Locke Dead At 74". RadarOnline. American Media, Inc. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- McNary, Dave (December 14, 2018). "Oscar Nominee Sondra Locke Dies at 74". Variety. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- Sondra Locke, Oscar-nominated actress, has died Sandra Gonzalez, CNN, December 14, 2018

- Sondra Locke Loses Her Battle with Cancer: Star Who Loved Then Sued Clint Dies at 74 Kelly Allen, The Mirror, 15 December 2018

- Welk, Brian (December 14, 2018). "Sondra Locke Remembered as 'Early Pioneer' for Women in Hollywood". TheWrap.

- "Locke Feels Vindicated After Lawsuit". Ann W. O'Neill, Los Angeles Times, September 29, 1996

- The rise of childlessness The Economist, July 27, 2017

- The Actor And The Revolutionary! NOTORIOUS Women podcast, December 25, 2018

- Fitzgerald, Mark. "Go Ahead, Make My Day : Locke vs. Eastwood Case Leads to Landmark Decision". Editor & Publisher, July 31, 1999.

- "Public, media have right to attend civil trials". Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. August 9, 1999.

- Dolan, Maura. "Court Leaning Toward Access to Civil Trials". Los Angeles Times, May 7, 1999.

- francesfisher on Instagram: "#RestInParadise dear friend #SondraLocke 12.14.18

- Rosanna Arquette🌎✌🏼 on Twitter: "I worked with Sondra Locke as a director in 1996. She was thoughtful and kind ..had laser vision she was great with actors. It is horrible to be black balled." / Twitter 12.13.18

- Gardner, Kate (December 14, 2018). "In Memory of Sondra Locke, Not Her Relationship". The Mary Sue.

- ‘She deserved better’: Star Sondra Locke’s obituary slammed online Hannah Paine, News.com.au, 15 December 2018

- Cills, Hazel (December 14, 2018). "This Is How a Woman Gets Written Out of Her Own Obituary". Jezebel.

- "Say, is that C.J. Cregg in Shelbyville?". Brad Schmitt, The Tennessean, April 27, 2004

- "Hollywood stars to help Shelbyville native's film". Brad Schmitt, The Jackson Sun, June 27, 2004

- "Shelbyville gets its close-up". Ken Beck, The Tennessean from Nashville, August 7, 2005

- "The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter - Sondra Locke and Alan Arkin". MSN. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- "Cover Me Babe". www.shockcinemamagazine.com. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- "RIP Willard Actress Sondra Locke". Horror Society. December 14, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- "Night Gallery - TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- "Shadow of Chikara (1977)". March 9, 2010. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- Sandra Locke appeared with Clint Eastwood in hit films Telegraph Retrieved December 18, 2018

- O'Connor, John J. (December 3, 1979). "TV: 'Friendships, Secrets and Lies'". Retrieved December 18, 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- "Bronco Billy (1980) – Svensk Filmdatabas". Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- "Actress Sondra Locke dies aged 74". December 14, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- "Interview: Sondra Locke Talks Clint Eastwood and the Fate of RATBOY". ComingSoon.net. September 29, 2015. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- "Actress and Director Sondra Locke, Clint Eastwood's Former Girlfriend of 14 Years, Dies at 74". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- McNary, Dave (March 22, 2018). "Film News Roundup: Keith Carradine-Sondra Locke's 'Ray Meets Helen' Gets Release". Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- Furtado, David (November 20, 2013). "Sondra Locke's Ratboy: A modern day fairy tale". Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- Gilbey, Ryan (December 14, 2018). "Sondra Locke obituary". Retrieved December 17, 2018 – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Death in Small Doses (1995)". Retrieved December 18, 2018 – via letterboxd.com.

- "Actress and Director Sondra Locke, Clint Eastwood's Former Girlfriend of 14 Years, Dies at 74". www.yahoo.com. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- "Several Days With the Days". The Nashville Tennessean. February 16, 1964.

- "Shivers Missing in 'The Innocents'". The Nashville Tennessean. June 18, 1964.

- "Erwin Has Rare Aplomb; Poise Brings Applause". The Nashville Tennessean. August 20, 1964.

- "'Tiger at the Gates' At Vanderbuilt Theater". The Nashville Tennessean. January 20, 1967.

External links

- Sondra Locke at IMDb

- Sondra Locke at the TCM Movie Database

- Sondra Locke at the British Film Institute

- Sondra Locke at Rotten Tomatoes

- Works by or about Sondra Locke in libraries (WorldCat catalog)