Solway Junction Railway

The Solway Junction Railway was built by an independent railway company to shorten the route from ironstone mines in Cumberland to ironworks in Lanarkshire and Ayrshire.

| Solway Junction Railway | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Solway Viaduct - Solway Junction Railway | |||

| Overview | |||

| Locale | Scotland | ||

| Continues as | Caledonian Railway | ||

| History | |||

| Opened | 13 September 1869 | ||

| Closed | 27 April 1931 | ||

| Technical | |||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) | ||

| |||

It opened in 1869, and it involved a viaduct 1 mile 8 chains (1.8 km) long crossing the Solway Firth, as well as approach lines connecting existing railways on both sides.

The viaduct was susceptible to damage from floating ice sheets, and the rising cost of repairs and maintenance, and falling traffic volumes as the Cumberland fields became uncompetitive, led to closure of the viaduct in 1921. The viaduct and the connecting railways were dismantled, and now only the shore embankments remain.

History

Conception

In the late 1850s, business interests were concerned to improve transport facilities for iron ore being mined in the area of Canonbie, in south Dumfriesshire close to the English border. Their intention was to bring the mineral to Annan Harbour (on the north shore of the Solway Firth), from where it could be forwarded by coastal shipping. They approached James Brunlees, a civil engineer with experience of coastal works. He advised against the scheme, which would have partly duplicated the Glasgow and South Western Railway (G&SWR) route, but he put them in touch with business people in Cumberland, who had engaged him to plan a railway from Cumberland iron deposits to a new harbour at Bowness, on the south shore of the Solway.

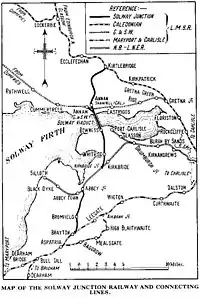

The two groups conferred, and revised their plans; they projected a railway that would cross the Solway by a viaduct, connecting existing railways on both sides of the Solway. At the time there was heavy iron ore traffic from Cumberland to Lanarkshire and Ayrshire ironworks, running by rail via Carlisle and the Caledonian Railway, the Glasgow and South Western Railway, or by coastal shipping. 92,000 tons of iron ore was exported from Cumberland to Scotland in 1863. The viaduct route would save considerable mileage and avoid congestion at Carlisle. The viaduct was to be the longest in Europe,[1] and overall the line from Kirtlebridge to Brayton would be just over 20.4 miles long – including branches the total length would be about 25 miles (40 km). Brunlees was the designing engineer for both viaduct and line.[2][3]

The parliamentary examination of the Dumfries and Cumberland (Solway Junction) Railway Bill took place in the 1864 session. The G&SWR objected to the scheme as tending to capture their traffic and divert it onto the Caledonian: this opposition was overruled, however,[3] and the company was authorised (as the Solway Junction Railway) on 30 June 1864, with capital of £320,000 and predicted cost of £315,000.[4][5] The first chairman of the company was James Dees of Whitehaven;[6] he was soon succeeded by Alexander Brogden.[7]

A further Act was passed in 1865 allowing deviations of the line in Cumberland.[8] In 1866 two bills were brought forward. A bill for a line from Brayton to join the Whitehaven Junction at Flimby (thus making the SJR independent of the Maryport and Carlisle) did not match its advance notice and was therefore rejected by Parliament,[9] but led to a satisfactory agreement with the M&C.[10][11] An Act was also passed authorising an increase in capital of £60,000 and further borrowing of £20,000: it also permitted the North British and the G&SWR to subscribe £100,000 each, should they so wish.[11] In 1867, a further Act was obtained; instead of running parallel to the Silloth railway (leased by the North British Railway), the Solway Junction would use running powers over it between Kirkbride and Abbey Holme.[12] The 1867 Act (as well as removing the opening span from the viaduct design) also confirmed the agreement with the Maryport and Carlisle and allowed the Caledonian to subscribe on the same basis as the North British and the G&SWR.[13] The Caledonian, alarmed at the possibility of the lucrative iron ore traffic being diverted off its system, acted (unlike the other companies) on the implicit invitation. In September 1867, an agreement whereby the Caledonian subscribed to £60,000 of 5% preference shares in the Solway Junction and operated the line was ratified by the shareholders of both companies.[14][15][lower-alpha 1]

Construction

The viaduct was effectively a trestle construction with 193 spans of 30 feet (9.14 m); each pier consisted of five cast iron columns of hollow section, 12 inches (305 mm) diameter; the outer columns were raked, acting as buttresses to the three inner load-bearing columns. The columns were founded on iron tubular piles that were driven by a steam pile driver, after an unsuccessful attempt to screw them in to the substrate. Originally, the viaduct was to be of 80 30-foot spans, the railway being carried on a solid embankment as far as the low-water mark on either side. A 36-foot opening span was to be provided to allow the passage of small craft to the upper Solway ( chiefly to Port Carlisle);[16] the Board of Trade however objected to so major an obstruction to tidal flows and required a 50-foot opening span to allow the passage of steam tugs. The promoters accepted both objections at first,[17] but the Bill of 1867 made no provision for an opening span, the promoters arguing that the traffic of Port Carlisle was negligible and should not be allowed to compromise the viaduct design. This argument won the day; although the Board of Trade confirmed its earlier stand that the traffic of Port Carlisle was not negligible,[18] Parliament was persuaded that it was insignificant in comparison to the projected traffic over the viaduct and as built the viaduct made no provision for ships to pass through it; this ended any commercial use of the harbour at Port Carlisle.

The cost of the viaduct and approach embankments was £100,000. It had 193 spans with 2,892 tons of cast iron for the piles and columns, and 1,807 tons of wrought iron in the superstructure; it was wide enough to take double track (if this was later required) but only single-track was laid. The greatest engineering difficulty on the line turned out not to be the construction of the viaduct, but the mile and a quarter (2 km) section of line over Bowness Moss on the Cumberland side. The Moss in its natural state was a raised mire "unsafe for cattle and horses", and considerable works had to be put in hand to establish a stable trackbed.

Opening

A trial trip was made on 26 June 1869, ahead of the Board of Trade inspection[19] and freight traffic started on 13 September 1869, with three mineral trains each way daily.[20] The line opened to passengers between Kirtlebridge and Bowness on 8 March 1870,[21] but the Board of Trade inspector would not approve passenger traffic over the Bowness Moss section until he was persuaded it had been adequately consolidated by goods traffic. After re-inspection on 23 July 1870 it was passed for passenger use: the first passenger train over the line (28 July 1870) was a 'special' from Aspatria to an agricultural show at Dumfries.[22] A regular passenger service - four trains a day between Kirtlebridge and Brayton, with intermediate stations at Annan and Bowness - began on 8 August 1870.[23] The station at Abbey Junction opened 31 August 1870.[24]

Financial difficulties

The mineral traffic never came up to the original expectations; by March 1871 the board were regretting that a fall-off in the volume of iron ore being sent into Scotland meant less traffic and lower revenues than anticipated. In the previous half-year revenue receipts had been £3741, working expenses £3487, and interest due on debentures £4036.[25] In 1873 the SJR sold the line between Annan and Kirtlebridge to the Caledonian for £84,000, the Caledonian paying a further £40,000 for land: the Act authorising this was also used to restructure the SJR's debt; its debentures were now to pay 3.5% rather than 5%.[26] The reduction in interest due was largely irrelevant; by March 1877, operating revenue in the previous half-year was still only £4560, and an operating profit of £1046 allowed a 2% per annum dividend to be paid on the debentures.[27] In the mid-1870s Spanish iron ore became readily and cheaply available and was shipped direct to Ayrshire ports, competing with Cumbrian ore. The SJR also subsequently alleged that it had been deliberately starved of much of the remaining traffic by the Maryport and Carlisle and the Caledonian, who continued to route traffic by Carlisle unless (and in some cases despite being) explicitly routed over the SJR by the consignee.[28] The iron traffic in the first half of 1878 was only one-third of that in 1877, the receipts for the half-year were under £2700 and the net operating profit was £104.[29] Arrears of interest on debentures was by then over £8,000.[30] There was a slight recovery, and by 1880 a dividend was again being paid on debentures, but the arrears of interest were accumulating. The company was therefore in no financial state to withstand the loss of the viaduct and a need for major expenditure to repair it.

Debacle

In the winter of 1874-75 longitudinal cracks appeared in a few columns; water was getting inside and freezing in cold weather. This happened on eleven load-bearing columns (which were replaced) and about twenty 'rakers' which were 'clipped'. To prevent any repetition, half-inch holes were drilled just above the high-water mark. Some braces were also broken by the impact of floating ice, but no columns were damaged.[31]

In January 1881 an exceptionally cold spell lasted most of the month, and ice accumulated in the upper estuary and the rivers feeding it. Sheets of ice up to six inches formed; fragments of these sheets rode over each other and froze together, leading to the formation of blocks of ice up to six feet (two metres) thick.[31] As the cold spell ended, the ice began coming down upon the viaduct about 25 January, but there was no damage to the structure until 29 January when much more ice was coming down. The maximum speed of water through the viaduct (at half-ebb) was about eight to ten miles an hour and the shock of ice floes hitting the piers could clearly be felt by anyone standing on the bridge; the noise could be heard a mile away. On the morning of 29 January three rakers and one load-bearing column were found to be damaged. The damage was assessed, running repairs made, and trains allowed to proceed over the viaduct under caution.[31] Over the course of 30 January, a number of piers gave way under repeated shocks; by the morning of 31 January it was found that five piers, consisting of five pillars each, were completely demolished, and that a great many single pillars in other piers had given way.[32] The ice continued to come down in large shoals, and inflict further damage; until, by 3 February:

The damage to the pillars begins at a distance of 400 yards from the English coast and extends in varying degree to about 100 yards from the Scotch side. In the intervening distance between these points there are altogether 44 entire piers gone, two of them double piers of 10 columns each; and other pillars have been broken at intervals in other places, making the total number of pillars broken over 300. In some places where piers are completely swept away the spans remain in position, but there are two complete gaps in the bridge where piers, girders, plates and railway have completely disappeared. These two breaches in the structure measure together between 300 and 400 yards.[33]

The winter of 1879-1880 had seen the Tay Bridge disaster, which the subsequent Board of Trade Inquiry (at which Brunlees had appeared as an engineer with considerable experience of the successful design of iron viaducts) had blamed on shoddy workmanship and egregious design decisions by Thomas Bouch. Sir Joseph Pease MP, noting that Brunlees had described the viaduct "as exactly the same in construction as the Tay Bridge" put a question in parliament to Joseph Chamberlain the President of the Board of Trade: "

whether this Bridge was inspected previous to its opening by an engineer appointed by the Board of Trade; and, if so, whether such engineer reported upon the danger which might arise from the pressure of floating ice; and, what steps he intends to take before the Solway Bridge is again opened for traffic in order to secure public safety, in the case of a second bridge of the same construction, which has proved to be unable to stand the pressure of storms or flood, and which have been both duly inspected by officers of the Board of Trade previously to their being opened for public traffic?"[34] [lower-alpha 2]

Major Marindin of the Railway Inspectorate conducted an enquiry to establish the cause of failure and hence make appropriate recommendations on the appropriate design of a reconstructed Solway Viaduct. He reported that failure was not due to the pressure of a large mass of ice piled up and jammed against the structure, but was a result of cumulative piecemeal failures of individual columns hit by ice floes:

when the momentum which would be acquired by a piece of ice twenty-seven yards square and in places six feet thick (the dimensions of one piece actually measured), upon a tide running at ten miles an hour is considered, it is not surprising that cast iron columns twelve inches in diameter, seven-eighths of an inch in thickness, which owing to the long-continued frost were in a very brittle state were unable to resist the shock. ... the close proximity of the piers prevented the ice from getting away so quickly as if the spans had been wide … masses of ice unable to escape were again and again dashed by the tide against the piers which they were unable to pass ... the floating blocks struck and broke column after column, until at last the whole of a pier succumbed after being destroyed piecemeal.

Reconstruction of the viaduct

In condemning Bouch's Southesk viaduct for defective foundations after rigorous testing, Colonel Yolland (the head of the Railway Inspectorate) had also stated his opinion that "piers constructed of cast-iron columns of the dimensions used in this viaduct should not in future be sanctioned by the Board of Trade.".[37][lower-alpha 3] Marindin's report noted that " This disaster furnishes a very convincing proof of the unreliability of small cast-iron columns when used for the piers of viaducts in positions where they are likely to be exposed to any blow or sudden shock" but drew a slightly different conclusion: that "it would be far better in future to avoid any such mode of construction." Consequently, Marindin stopped well short of requiring any reconstruction of the viaduct to use only wrought-iron columns: "I do not, however, consider that the reconstruction of this viaduct need be objected to provided due care is taken, either by the erection of timber ice fenders or by the substitution of wrought iron rakers of sufficient strength to withstand the blows of the floating ice, to guard the cast iron bearing columns from any such danger… And it is worthy of consideration whether it would not be better to increase the width of the spans at the centre of the channel, so as to permit the ice to pass more freely than it does at present."

Reconstruction of the viaduct began in the summer of 1882: in the rebuilt viaduct, the three inner columns in each pier were still cast-iron, but the two outer 'rakers' were each a single wrought-iron tube filled with concrete and provided with timber ice fenders. The original raker foundation piles were retained, but cast-iron clips were bolted around them, and the annulus between clips and pile filled with cement.[38] Although by August 1883 the viaduct reconstruction was sufficiently far advanced that construction traffic was run over it,[38] passenger services over the line did not resume until 1 May 1884.[39]

Dependency on the Caledonian

The Solway Junction Railway obtained (1882) a Bill allowing it to raise another £30,000 to fund the reconstruction of the viaduct, the additional debt taking precedence over all previous borrowings or shares, including £60,000 of preference shares held by the Caledonian. The SJR wished to grant the North British running powers and did not want to raise the money by further indebtedness (and dependency) to the Caledonian, which they believed was using its lease of the SJR to damage the interests of SJR shareholders. The Caledonian was prepared to lend the £30,000 as a 4% first-debenture stock, taking precedence over the SJR's debentures and its existing preference shares, but only if the NBR were not given running powers over the SJR.[40] The Caledonian subsequently went to court, obtaining a judgement that its agreement of 1867 with SJR under which the Caledonian had first refusal on any further issue of SJR stock precluded the SJR raising the money by other means, such as mortgages.[41] The SJR, arguing that clauses in its 1882 Act if correctly interpreted removed the Caledonian's right of first refusal, went to the Appeal Court, which found in their favour;[42] The Caledonian took the case to the House of Lords, the final judgement (in July 1884) being that the Caledonian was not entitled to insist that their offer to take up first-debenture stock denied the SJR the right to consider other means of raising the money; the Caledonian appeal was therefore dismissed with costs, provided that the SJR promised that whatever means of raising the money they decided upon, the Caledonian would have first refusal.[43]

The SJR also sought to lessen its dependence on the Maryport and Carlisle, but was unsuccessful. Clauses in the SJR's 1882 Bill which would have given it running powers from Brayton to Maryport were rejected. In 1883 the SJR promoted a Bill for a line to run from Brayton to Bassenthwaite Lake on the Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith Railway and the Cleator and Workington Junction Railway promoted a Bill to build a line from Calva Junction, immediately north of Workington, to Brayton. Either line would have given the SJR the possibility of through traffic that could not be intercepted by the M&CR, and both were opposed by the M&CR.[44] The SJR's Bill was defeated,[45] and whilst the C&WJR got its Act it then came to a compromise with the M&CR which dashed the SJR's hopes; the new line ran from Calva Junction only to Linefoot, on the Derwent branch of the M&CR, the M&CR granting the C&WJR running powers between there and Brayton.

In 1889, a faction of the SJR board, after a couple of stormy shareholder meetings[46] and proxy battles, ousted other directors and secured agreement by shareholders to a deal with the Caledonian; the Caledonian would take up the £30,000 first debenture stock at 3½%, provide half the SJR's directors, and for half the traffic receipts would meet both the operating and maintenance costs of the SJR.[47] The SJR was also have the option (which in due course they exercised) of converting the £60,000 of preference stock originally subscribed by the Caledonian into £90,000 of SJR ordinary stock. The agreement came into force in June 1889, and subsequently supported by the Caledonian's private Act of 1890.[48] This effectively ended the existence of the Solway Junction Railway as an independent entity, although it was not until 1895 that it was amalgamated with the Caledonian. The company, however, survived; SJR shares and stock held by the Caledonian were cancelled, and the rest were converted not into Caledonian securities, but into a new SJR security paying 3% a year, financed by an annual payment of £4,500 a year from the Caledonian.[49] Grateful SJR shareholders voted the directors £100 each and the secretary £1000; that Christmas the chairman gave £70 of his £100 'for distribution among the men' (estimated to number about 50) .[50]

Maintenance deferred, and closure

In 1914 an assessment of the maintenance needs of the viaduct was carried out. The long metal structure exposed to a marine atmosphere had deteriorated and £15,500 would need to be expended in maintenance work. The work was suspended on the outbreak of World War I, which saw increased use of the viaduct for iron-ore and pig-iron traffic from West Cumbria to Scotland.[51] It was announced that stations south of the viaduct were to be closed from 1 February 1917 [52] but this decision was promptly rescinded[53] The creation of a large munition works at Eastriggs, to the east of Annan, gave the line additional traffic; including (in May 1917) the Royal Train, carrying King George and Queen Mary on a four-day tour of that and other munitions factories.[54]

The Yorkshire Post reported in May 1921 that the Caledonian had closed the branch for both goods and passenger traffic; an engineering inspection of the viaduct had concluded that it was 'defective, and unsafe for the traffic' (but it was also said that the closure had been accelerated by the current miners' strike): all stations south of the Solway were therefore closed.[55] When a local MP asked a parliamentary question on the closure in July 1921, the Minister of Transport said that the Caledonian were awaiting an abatement in post-war prices before they could consider the necessary repairs; the traffic the viaduct might carry was now much reduced, and such as remained could easily be routed via Carlisle.[51] The estimated cost of repair was £70,000.[56] In 1926, the London Midland and Scottish Railway confirmed that it had no intention of ever resuming passenger services on the Solway Junction.[57] Until demolished, the viaduct was used by pedestrian trespassers, most notably on Sunday from Annan (where drinking establishments did not open on a Sunday) to Bowness (where they did).[58]

Dismantling

Any future use of the viaduct was impossibly expensive, and after a period of dormancy, in 1933 arrangements were made to demolish it. Arnott, Young and Company purchased the bridge and dismantled it; much of the material found a second use, and some of the metal was used by the Japanese forces in the Sino-Japanese War. During the work three men lost their lives when attempting extraction of one of the piles; the men were inexperienced in boat work and their boat was caught in strong currents and capsized.

The dismantling of the viaduct was completed by November 1935, but sections of the pier foundations remained in the bed of the estuary. The section of railway between the south end of the viaduct and Kirkbride Junction was dismantled as part of the process.

The section of line between Abbey Junction and Brayton continued in use, as part of the Maryport and Carlisle section, until closure after 4 February 1933.

Passenger trains ceased operating on the northern section between Kirtlebridge and Annan from 27 April 1931. A twice-weekly goods service ran to Annan from the G&SWR line, reversing at a headshunt towards the former viaduct. This arrangement was discontinued in January 1955.[2]

Since closure

During World War II an RAF airfield was created near Creca, north of Annan, and part of the original line from Kirtlebridge to that point was reinstated.[59][60] The line was dismantled some time in the 1960s.

In 1959 Chapelcross nuclear power station was opened; the location is on the east side of the former line about halfway between Kirtlebridge and Annan, close to the RAF station site. It is likely that the RAF station line was used to bring in construction materials. Liquid effluent from the power station was discharged into the Solway Firth at Annan and at least the final part of the railway alignment was used to route the effluent pipes. The power station is no longer operational, having closed in 2004.

Locomotives

The Solway Junction Railway decided from the outset to work its own line. It acquired four locomotives from Neilson and Company. Nos. 1 and 2 were 0-4-2 well tanks and nos. 3 and 4 were 0-4-2 tender engines. In 1868 two further locomotives were ordered; nos 5 and 6 were 0-6-0 tender engines, also from Neilson; they never bore their SJR numbers, going straight to the Caledonian Railway numbering series. The final locomotive considered to belong to the SJR route was a small-wheeled 0-6-0 saddle tank, built by Manning Wardle and acquired second hand for shunting work. In January 1872 it was disposed of to the Wigtownshire Railway.[2]

Route

The line ran south from Kirtlebridge on the Caledonian Railway Main Line through undulating country to Annan Shawhill station. The line descended to the Solway viaduct, and a west-to-south spur from the G&SWR Annan station trailed in. At the south side of the Solway, Bowness station was reached, and the line then passed across the marshy terrain, then reaching Whitrigg, before connecting with the Carlisle and Silloth Bay Railway at Kirkbride Junction. The through route used that railway as far as Abbey Junction, from where the Solway Junction Railway's own route ran via Bromfield to Brayton, where it joined the Maryport and Carlisle Railway route.[2]

Locations on the line were:

(Note: locations in italic were not passenger stations.)

- Kirtlebridge; junction station on the Caledonian Railway;

- Annan; opened 1 October 1869; advertised locally only; nationally advertised from 8 March 1870; renamed Annan Shawhill in June 1924;[1] closed 27 April 1931;

- Bowness; opened 8 March 1870;

- Whitrigg; opened 1 October 1870;

- Abbey Junction; opened 31 August 1870;

- Broomfield; opened 1 March 1873; renamed Bromfield 1895.[61]

Connections

- Caledonian Railway Main Line at Kirtlebridge

- Glasgow and South Western Railway at Annan

- Carlisle and Silloth Bay Railway and Dock Company at Kirkbride and at Abbeyholme

- Maryport and Carlisle Railway at Brayton

Notes

- Agreement in principle had been reached in March 1867, before the NBR acceded to the SJR's request for running powers over the Silloth railway. Doubtless, said the SJR chairman, had the NBR known the SJR would never have got running powers.

- The Board of Trade's involvement with the SJR was at two different points in the process: before a Railway Bill was considered by a parliamentary committee the Board of Trade submitted a report on the anticipated effect of the railway on roads and navigable waterways, but not on the viability of the engineering design of its structures;[35] before passenger services could run on a newly-constructed line the Railway Inspectorate were required to report on the "completeness of the works and the adequacy of the establishment"; again with no requirement or powers to report on non-blatant design flaws ( a generation earlier an Inspector's non-SQEP objections to the design of the Torksey viaduct had caused indignation at the Institution of Civil Engineers, the threat of a parliamentary enquiry, and a retreat by the Inspectorate.) The Board of Trade had defended itself from criticism that the defects in the Tay Rail Bridge design detected or alleged after its failure should have been seen and acted upon by the Railway Inspectorate before the bridge was opened for passenger traffic: "The duty of an inspecting officer, so far as regards design, is to see that the construction is not such as to transgress those rules and precautions which practice and experience have proved to be necessary for safety. If he were to go beyond this, or if he were to make himself responsible for every novel design, and if he were to attempt to introduce new rules and practices not accepted by the profession, he would be removing from the civil engineer, and taking upon himself a responsibility not committed to him by Parliament."[36]

- The Southesk viaduct column diameters were 'about the same as those in the Tay Bridge' (fifteen inch and eighteen inch) according to Yolland. Yolland's concern was the vulnerability of Bouch's bridges to single-point failure (loss of a single column could have a domino effect, leading to rapid and catastrophic collapse of the structure) - the accounts of the slow destruction of the Solway Viaduct paint a very different picture, which may explain Marindin taking a different view from his boss.

References

- Gordon Stansfield, Dumfries & Galloway's Lost Railways, Stenlake Publishing, Catrine, ISBN 1 84033 057 0

- Stuart Edgar and John M Sinton, The Solway Junction Railway, Oakwood Press, Headington, 1990, ISBN 0 85361 395 8

- "The Solway Junction Railway - The Preamble Proved". Carlisle Journal. 6 May 1864. p. 7.

- Abridged prospectus printed as advertisement - "Solway Junction Railway Company". Whitehaven News. 8 September 1864. p. 8.

- E F Carter, An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles, Cassell, London, 1959

- (advertisement): "Solway Junction Railway Company". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 16 August 1864. p. 4.

- Notice of second half-yearly meeting printed as advertisement - "Solway Junction Railway Company". Whitehaven News. 16 February 1865. p. 1.

- advertisement:"Solway Junction Railway". Carlisle Journal. 29 November 1864. p. 2.

- "Solway Junction Railway". Carlisle Journal. 9 March 1866. p. 5.

- "Maryport and Carlisle Railway". Whitehaven News. 16 August 1866. p. 5.

- "Railway Intelligence - Solway Junction Railway". Whitehaven News. 9 August 1866.

- "North British Railway". Saturday Supplement to the Carlisle Journal of Friday. 29 March 1867. p. 1.

- "The Solway Junction Railway". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 6 August 1867. p. 5.

- "Caledonian Railway". Carlisle Patriot. 27 September 1867. p. 7.

- "Solway Junction Railway". Carlisle Journal. 1 October 1867. p. 3.

- "Dumfries and Cumberland (Solway) Junction Railway Bill". The Scotsman. 21 March 1864. p. 3.

- "Railway Bridge across the Solway". Carlisle Patriot. 12 October 1866. p. 6.

- "The Trade of Port Carlisle". Carlisle Journal. 15 March 1867. p. 4.

- "Solway Junction Railway". Glasgow Herald. 29 June 1869. p. 7.

- "The Solway Junction Railway". Glasgow Herald. 14 September 1869. p. 4.

- "Kirtlebridge - Solway Junction Railway". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 8 March 1870. p. 6.

- "Local and District News". Carlisle Patriot. 29 July 1870. p. 5.

- "Solway Junction Railway". Carlisle Patriot. 12 August 1870. p. 5.

- "Solway Junction Railway". Whitehaven News. 29 September 1870. p. 4.

- "Railway Intelligence - Solway Junction Railway". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 4 April 1871. p. 6.

- "The Solway Junction Railway Bill". The Scotsman. 23 May 1873. p. 5.

- "Public Companies". Evening Standard. London. 30 March 1877. p. 6.

- "Solway Junction Railway Bill". The Scotsman. 24 May 1882. p. 7.

- "Money Market". Leeds Mercury. 24 September 1878. p. 4.

- "Commercial - Agricultural and Commerce". Leeds Mercury. 1 October 1878. p. 7.

- "The Solway Viaduct Disaster". Glasgow Herald. 22 February 1881. p. 6.

- "Serious Injury to the Solway Railway Viaduct". Glasgow Herald. 2 February 1881. p. 6.

- "The Damage to the Solway Viaduct". Edinburgh Evening News. 4 February 1881. p. 2.

- "RAILWAYS—THE SOLWAY BRIDGE". Hansard House of Commons Debates. 258: cc340-1. 8 February 1881. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- "RAILWAY ACCIDENTS". Hansard House of Commons Debates. 93: cc240-3. 8 June 1847.

- "Report by the Board of Trade". Dundee Courier p3. 23 July 1880. p. 3.

- "Colonel Yolland's Report on the Southesk Viaduct". Dundee Advertiser. 18 December 1880. pp. 6–7.

- "The Solway Viaduct". Dundee Advertiser. 31 August 1883. p. 10.

- "Re-Opening of the Solway Junction Railway". Glasgow Herald. 2 May 1884. p. 10.

- "Solway Junction Railway". Glasgow Herald. 23 May 1882. p. 7. and "Solway Junction Railway Bill". Glasgow Herald. 24 May 1882. p. 8.

- "Judgement in a Railway Dispute". Dundee Advertiser. 22 November 1882. p. 6.

- "Caledonian Railway v. Solway Junction Railway". Glasgow Herald. 7 December 1883. p. 8.

- "House of Lords Appeal". The Scotsman. 8 July 1884. p. 3.

- "Miscellaneous: Maryport and Carlisle Railway". Liverpool Mercury. 16 February 1883. p. 8.

- "Miscellaneous - Solway Railway Meeting". Liverpool Mercury. 28 September 1883. p. 8.

- "Solway Railway Junction Meeting". Carlisle Patriot. 29 March 1889. p. 5.

- "Solway Junction Railway Company - Animated Meeting in London". Carlisle Patriot. 21 June 1889. p. 5.

- "Solway Junction Railway Company - Agreement with the Caledonian Railway Company". Leeds Mercury. 13 September 1890. p. 6.

- "The Solway Junction Transfer". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 14 February 1895. p. 5.

- "Mr Musgrave and the Solway Junction". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 24 December 1895. p. 4.

- "Imperial Parliament - House of Commons - Monday 18 July - The Solway Viaduct". The Scotsman. 19 July 1921.

- "Border News in Brief". Southern Reporter. 25 January 1917. p. 6.

- (advertisement): "The Caledonian Railway Company - Solway Branch Railway". Daily Record. Glasgow. 2 February 1917. p. 2.

- "The Royal Visit - King and Queen Visit Dumfriesshire Factory". Dumfries and Galloway Standard. 19 May 1917. p. 4.

- "Solway Railway Viaduct Closed". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 21 May 1921. p. 11.

- "Solway Railway Viaduct - Demolishment to Start This Week". The Scotsman. 7 May 1934. p. 12.

- "Railway Economies - Solway Junction Section". The Scotsman. 4 August 1926. p. 12.

- "Trespassing on Solway Viaduct". The Scotsman. 1 June 1925. p. 9.

- Canmore site: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland: Annan Airfield

- Secret Scotland Website: RAF Annan

- M E Quick, Railway Passenger Stations in England Scotland and Wales—A Chronology, The Railway and Canal Historical Society, 2007, ISBN 9780901461575

Sources

- Aston, G.J. and Barrie, D.S. (1932) "The Solway Junction Railway", Railway Magazine, 70 (415), p. 26–34

- Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 1-8526-0049-7. OCLC 19514063. CN 8983.

- Stuart, Edgar; Sinton, John M. (1990). The Solway Junction Railway. Headington, Oxford: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-8536-1395-8. OCLC 25654930.

- Jowett, Alan (March 1989). Jowett's Railway Atlas of Great Britain and Ireland: From Pre-Grouping to the Present Day (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-086-0. OCLC 22311137.

- Stansfield, Gordon (1998). Dumfries and Galloway's Lost Railways. Stenlake. ISBN 978-1-8403-3057-1. OCLC 40801310.

- Suggitt, Gordon (2008) Lost Railways of Cumbria, pp 107–112, ISBN 978-1-84674-107-4.